Cecilia Danysk, Amanda Eurich, Laurie Hochstetler

Western Washington University

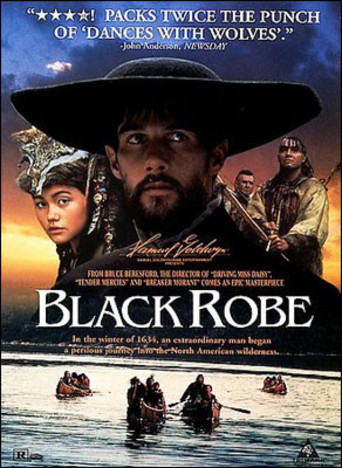

Bruce Beresford’s stunning 1991 cinematic adaptation of Brian Moore’s novel, Black Robe, is now more than twenty years old. Even with the passage of time, the film has lost little of its visual impact. Like the novel, Beresford’s film tells the story of a young Jesuit priest, Father Paul Laforgue, on his first mission to New France in 1634. The film follows Laforgue and his Algonquin guides, led by Chomina, on an arduous 1500-mile journey deep into the Canadian hinterland and Huron territories. Laforgue is joined in his travels by a handsome Frenchman, Daniel, drawn to the possibilities of the priesthood and the religious life. The expedition proves to be a feat of physical endurance that exposes Laforgue to the material and spiritual realities of the pilgrimage he has undertaken and tests his resolve to see it through. The deliberately slow pace of the film and Beresford’s wide angle shots of the majestic Canadian wilderness are repeated reminders of the fragility of the Jesuit/colonial enterprise and the insignificance of Europeans to this new world they hoped to transform. Long days canoeing through the wilderness are punctuated by bouts with dysentery, disorientation, and a decisive meeting with a Montagnais shaman, who convinces Laforgue’s Algonquin guides to abandon their Christian charge because he is a devil. Even Daniel follows their lead, drawn by his attraction to Chomina’s daughter, Annuka, and to Native culture. Although the party eventually decides to recover Laforgue, they are taken hostage by a band of hostile Iroquois, who drag them back to camp to torture them and then kill some of their number. During a harrowing escape from their captors, Chomina is fatally wounded. As he lies dying, he refuses Laforgue’s desperate efforts to convert him, convinced by his vision of the She-Manitou of  the reality and power of the Native spirit world. As winter closes in, Laforgue finally reaches the desolate Huron settlement, only to find it decimated by disease, his predecessors dead or dying. The remaining Huron survivors beg the new priest to offer them the benefits of his water sorcery, Catholic baptism. The film closes on a poignant note as one of the Huron leaders asks Laforgue if he loves them. As the faces of the Natives he has met on his journey pan over the screen, Laforgue offers up a halting yes. A postscript superimposed on the screen as the sun rises over the village reminds viewers that Iroquois raids would destroy the christianized Hurons and the French missions among them fifteen years later.

the reality and power of the Native spirit world. As winter closes in, Laforgue finally reaches the desolate Huron settlement, only to find it decimated by disease, his predecessors dead or dying. The remaining Huron survivors beg the new priest to offer them the benefits of his water sorcery, Catholic baptism. The film closes on a poignant note as one of the Huron leaders asks Laforgue if he loves them. As the faces of the Natives he has met on his journey pan over the screen, Laforgue offers up a halting yes. A postscript superimposed on the screen as the sun rises over the village reminds viewers that Iroquois raids would destroy the christianized Hurons and the French missions among them fifteen years later.

Black Robe has been severely (and perhaps fairly) criticized for its treatment of Native culture.[1] As James Axtell has noted, the Algonquin guides speak Cree rather than Algonquin or Mohawk. Even more problematic is the depiction of the Iroquois raids on Huron territory which suggests that killing Native captives was the norm. Studies of the Iroquois mourning wars have shown that they often integrated captives into the community to replace their own dead lost in battle or to illness.[2] Nor is there evidence for the kind of alternative sexual behavior that Moore projects upon his Native subjects, who “do it like dogs in the dirt,” to use Ward Churchill’s famous phrase.

In spite of these criticisms, a quick Internet search suggests that Black Robe remains a classroom staple, as it is in the history department at the university where we teach.[3] Cecilia Danysk uses the film in a course on colonial French Canada; Laurie Hochstetler in a course on colonial America. Amanda Eurich teaches it as part of a module on Catholic reform and renewal in her survey of early modern Europe. We discovered, to our surprise, that we tend to pair different readings with the film. This is a fine demonstration of the film’s capacity to address a variety of pedagogical, historical, and historiographical concerns. Our conversations have deepened our appreciation of the rich subtexts of the film as well as the historiographical traditions upon which we each draw to turn Black Robe into a useful classroom exercise. This broader vision will certainly inform our teaching of the film in the future.

Black Robe and New France

Cecilia Danysk

One of the challenges of teaching Canadian history to American undergraduates is to sensitize them to them to the differences between histories and cultures that, at least on this side of the border, are often blurred. New France was not New England. While most of the film focuses on Laforgue’s journey to Huronia with his Alquoquin guides, it also briefly explores the rough and ready nature of life in the European settlements of New France. Early scenes evoke the precarious political power of the French in Quebec, which is depicted as a frontier trading post as much as an outpost of empire. Samuel de Champlain, who makes a brief appearance in the film, comes off as less than the heroic figure of Canadian nationalist tradition. One of the most striking sequences early in the film shows Champlain and his Algonquin counterparts donning ceremonial dress in preparation for their first encounter. As the camera pans back and forth between Champlain and Chomina readying themselves for their meeting, the film underscores the parallels between Native and European pageantry and politics. The film also presents a relatively complex image of the colonies and peoples of New France. The character of Daniel underscores the fluid lines of life and identity along the frontier. The presence of three distinct Native nations and different groups of French settlers (royal officials, coureurs des bois, and Jesuit priests, all inspired by different mandates and answering to different authorities) undercuts any facile representation of colonial society. All the more reason why the Iroquois plotline is frustrating, both for its gratuitous violence and the stereotyping of the Iroquois as savage and the Alquonquin and Huron as virtuous. Those Native peoples who cooperated with the French are portrayed as peaceful, obliging, and credible economic partners.

Still, Beresford and Moore manage to create a world where Natives are powerful intermediaries and interpreters of the political and geographic landscapes. One of the strengths of both film and novel is the way they explore Native culture and cosmologies. The seeming superiority of European culture (Native wonder at European technology—mantle clock and the mysterious power of reading) does not obscure the enduring power of Native spirituality. The film’s exploration of Native dream worlds offers an important counter-narrative to the Christian narrative of conversion and redemption.

Students react enthusiastically to the sense of historical immediacy in Black Robe, as visceral understandings of the lives of people in the past give them an opportunity to consider their worldviews, motivations, and the boundaries placed on their choices. At the same time, their strong reactions to the film open the door for discussion of some of the film’s misrepresentations, and to a broader discussion of historical methodologies.

In a written exercise, students compare interpretations and use of evidence in Black Robe with selected primary and secondary sources,[4] analysing aspects covered in all three, such as religious systems, gender relations, trade, authority, etc. Since the film and secondary sources rely heavily on the Jesuit Relations, students have ample scope to examine similarities and differences, and to learn how to develop evidence-based analysis. Although some students have difficulty perceiving interpretation in primary sources and even more so in cinematography, most learn to look more closely and more critically at how evidence is used and how arguments are constructed.

As a tool for examining historical issues, Black Robe challenges students to think critically about colonialism, relations between First Nations and Europeans, gender, ideologies, and so on, particularly when we consider the film as a counterpoint to the secondary sources assigned for the class. I show the film near the beginning of the course and we talk about the early contact period’s creation of the ‘Other’. Using D. Peter MacLeod’s work, we then address what shapes attitudes, what influences judgments, and how perceived identities influence behaviors.[5]

Later in the course, the film comes up in our discussion of the role of gender in Native and missionary societies, as we address the debate among Eleanor Leacock, Carol Devens and Susan Sleeper-Smith.[6] When methods and use of warfare come up, a perennial favorite, we compare the film’s depiction of the Iroquois attack and torture of captives with the work of Jose Antonio Brandão and D.K. Richter.[7]To emphasize the complexity and fluidity of Native-French relationships, we refer back to the film and to Richard White’s work to assess how the early contacts may have influenced those changing relationships.[8]

The film proves particularly useful when we come to analyse Native sovereignty, an issue that students find difficult, predisposed as they often are to regard the English ideas of Native sovereignty during the American colonial period as the norm. As we study the work on New France by John Dickinson and Cornelius Jaenen,[9] we hark back to the film’s portrayal of power relations between French and Algonquin, including the very tenuous foothold of the French in North America and their absolute reliance on their Native allies for the fur trade. The film also helps students grasp the complex intertwining of trade, diplomacy, war, missionary activity, and disease.

Black Robe and the American Colonies

Laurie Hochstetler

In preparation for viewing Black Robe, students in my colonial America course read Daniel Richter’s Facing East from Indian Country.[10] Covering centuries and continents, Richter’s work explains macro-historical changes whose effects are apparent in the early-seventeenth-century northeast. In particular, Richter describes population decline and reconfiguration, a broad series of changes experienced by the Hurons, Algonquins, and the Iroquois. Students learn that North America at the time of first contact was a continent in crisis. They learn that in many cases people were the most valuable resource for Native American nations; this necessity led to the rough treatment of Chomina’s party by the Iroquois. Likewise, they learn about the changing character of North American trade, as Native peoples became more dependent upon trade with Europeans for manufactured goods.This is made evident in Native traders’ desire for muskets, above all things, in their trade with Europeans.[11]

Students also read selections from The Jesuit Relations.[12] Viewing Black Robe in conjunction with The Jesuit Relations allows them to see how historians compile and organize primary source information, and use it to tell broader stories. Many students have commented that Black Robe seems to them like The Jesuit Relations illustrated. They are able to see how Brian Moore has taken information from various Jesuit writings to formulate a narrative. The visual experience of Black Robe helps to underscore essential themes in the history of early America.

Black Robe richly illustrates several key concepts that are often difficult for students to grasp. Constant competition and its resulting violence were normative experiences in colonial North America. As a contested space where American, European, and African peoples met, and where they negotiated old and new relationships of enmity, violent encounters were an expected part of life. Chomina and Laforgue’s party are most notably exposed to such violence during their captivity and torture at the hands of the Iroquois. Yet even when engaging in warfare, as Chomina’s party’s shows, providing for the future was a constant concern: the need to complete their hunt in time and to reach their winter grounds before the snow overwhelms them. Students tend to see colonial America through a pastoral lens, a series of peaceful, rural communities where life was confined to providing for daily subsistence. The film reminds them that violence was the rule rather than the exception, and that provisioning was the principal worry of all.

Laforgue’s decision to voyage to New France, and his consequent experiences, highlight the insignificance of colonial enterprises. Laforgue’s mother is hardly pleased with her son’s decision to become a missionary; she would gladly have seen him married to a pretty Frenchwoman with genteel musical accomplishments (as we learn in a flashback). . As Laforgue sets off for New France, his mother has already put on mourning attire, grieving her son’s death even before they have parted. Laforgue’s mother recalls the parents Barbara Diefendorf describes, who must deal with their children’s decision to enter the Church at the height of the Catholic Reformation.[13] The veteran New France missionary, complete with scars and amputations from Iroquois torture, seems out of place, rather than heroic, juxtaposed to the symmetry and decorations of a Gothic church. The old priest stresses that missionary work in North America is of great importance, but the elegance of the church, and the well-dressed, handsome aspect of the clean-shaven Laforgue provide a constant, if unspoken, counterpoint. Across the Atlantic Champlain attends to political matters with the ceremonial trappings of a French diplomat, but his efforts seem to have little effect on those back home.

In the film’s final scene of a mass baptism at the Huron mission, the music shifts from an orchestral score whose rhythms suggest a natural and unspoiled landscape, to Catholic sacred music. This auditory shift leaves students feeling that they are witnessing a world undergoing similarly profound and jarring transitions. Students often come to a course in colonial America believing that they know the story of European missionary endeavors. Missionaries arrived with high ideals and a certain amount cultural chauvinism; their enterprise caused the downfall of a people. Black Robe is essential to my efforts to show them that the story is not so simple, the balance of power not so clearly tilted towards Europeans, and that all parties were perhaps more adaptable than they expected.

Black Robe and the World of Catholic Reform and Renewal

Amanda Eurich

My use of the film is admittedly Eurocentric. Students read several chapters from Craig Harline and Eddy Put’s engaging history of Mathius Hovius, the late sixteenth-century archbishop of Mechelen (in present-day Belgium) and his struggles to bring parishioners, clergy and Anabaptist heretics into conformity with Tridentine Catholicism.[14] A Bishop’s Tale humanizes the administrative reforms and bureaucratic impulses that characterized Catholic reform efforts in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In Hovius, students encounter a militant reformer with considerable resources at his command, who is more often than not frustrated by his constituents. He battles the intransigent beer-brewing monks of Affligem, Benedictine nuns resisting enclosure, and canons more interested in hunting and drinking than carrying out their spiritual responsibilities. Even Hovius’ investment in a promising young school boy, plucked from obscurity to be the shining star in his new seminary, fails when Jan Berchman jumps ship and joins the Jesuits as a novice with missionary ambitions. This colorful slate of real-life characters sets the stage for our viewing and discussion of Black Robe.

Black Robe provides students with a useful contrast to the parish politics and clerical rivalries at the heart of A Bishop’s Tale, by exploring the new spirit of interiority that was also a hallmark of the world of Catholic reform.The cinematography captures the loneliness of the missionary enterprise and the spiritual impulses that inspired it.[15] The decision to cast the French Canadian actor, Lothaire Bluteau, famous for his lead role in Jesus of Montréal, was surely intentional, even if the reference is often missed by American students. An early flashback sequence in the film prompts discussion of the external and internal forces that propelled Laforgue to the Canadian frontier. We see Laforgue serving as an acolyte to a crusty old priest whose face bears the scars of brutal mutilation by Native hands, an image probably taken from Jérôme Lalemant’s description of the tortures suffered by Isaac Jogues at the hands of his Native captors, in the Relations.[16] Even while calling his captors savages, the priest tells Laforgue he plans to return to the “glorious task.” This exchange reminds students of the fluid traffic between the Old World and the New that nourished the heroic narratives of Jesuit missionizing efforts.[17] The sequence also lends itself to discussions of the culture of self-abnegation and even self–mutilation that formed a part of the new spirit of piety.[18] Laforgue may not be prepared for the physical and spiritual challenges he faces, but he almost certainly expects that his mission will entail physical suffering. For Laforgue suffering legitimizes the slow halting steps toward his end goal, the conversion and baptism of natives. Or is the goal to imitate the suffering of Christ?

In preparation for the discussion of the film, students also read letters from the Jesuit Francis Xavier written from India to the Order’s headquarters in Rome in the mid-sixteenth century.[19] In many ways, Xavier’s letters parallel the film’s narrative and beg the question: how did early modern Catholic and Protestant reformers understand christianization? Were the requirements imposed on indigenous communities of New France any different from those imposed by parish priests (or for that matter, Protestant pastors) in Europe? Students note that Xavier, like his counterparts in Europe, relies on rote memorization and catechetic instruction. Like Laforgue, he baptizes whole villages driven by illness to seek out a new faith. And much like his Protestant counterparts, Xavier is a bitter opponent of idol worship, encouraging acts of iconoclasm by eager children among his recruits. In Xavier’s letters there is no room for the sentimental reflections found in the last scenes of Moore’s film script. The disparity between the primary sources and the film often prompts a vigorous discussion of the intentions/motives of Jesuit missions. Can Laforgue’s response really be treated as genuine? Is it characteristic of Jesuit interactions with their indigenous converts?

Black Robe is a film well worth revisiting. For all its frustrating flaws, it captures the attention of a visually oriented generation of students. Much like the Atlantic world in which it is set, Black Robe explores the divergent concerns, beliefs and practices of the peoples who encountered each other in the contested cultural landscapes of northeastern North America.

Bruce Beresford, Director, Black Robe, Color, 1991. 101 min., Canada, Australia, USA, Alliance, Communications Corporation, Samson Productions Pty. Ltd., Téléfilm Canada

Brian Moore, Black Robe, McClelland and Stewart, Dutton, Jonathan Cape, 1985

- See Ward Churchill, “And they did it in like dogs in the dirt: An American Indian Analysis of Black Robe,” Indian are Us? Culture and Genocide in Native North America, (Monroe: Common Courage Press, 1994), 115-37; see also James Axtell, “Black Robe,” in Mark C. Carnes, ed., Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies, (New York: Holt, 1995), 78-81.

- Scholars have used the term, “mourning wars,” to describe a well-documented function of Iroquois raiding parties: revenge and the replacement of family lost in war or to the epidemics unleashed by European contact. In these wars, captives were often adopted by the Iroquois so that the social community could continue undisrupted. See Daniel Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

- See for example Edward Gallagher’s website, http://digital lib.lehigh.edu/trial/reels/films/hst1_4_7, which offers an extensive bibliography of journal articles and reviews of the movie. See also http://worldhistory connected.press.illinois.edu/4.2/fr_umbach3.html.

- Students use Allen Greer’s collection, The Jesuit Relations: Natives and Missionaries in Seventeenth-Century North America (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s 2000), especially the sections by Pierre le Jeune, 1633-34), 21-36; and Marie de l’Incarnation: “Trials Among the Hurons” in Joyce Marshal, ed. & trans., Word from New France: The Selected Letters of Marie de l’Incarnation (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1967), . See also Peter Goddard, “Converting the Sauvage: Jesuit and Montaignais in Seventeenth Century New France” Catholic Historical Review 84:2 (1998), 219-239; and/or Carole Blackburn, Harvest of Souls: The Jesuit Missions and Colonialism in North America, 1632-1650 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000).

- D. Peter MacLeod, “The Amerindian Discovery of Europe: Accounts of First Contact in Anishinabeg Oral Tradition” Arch Notes 92:4 (July /August, 1992), 11-15, for a First Nations perspective.

- Eleanor Leacock, “Montagnais Women and the Jesuit Program for Colonization” in Women and Colonization: Anthropological Perspectives, ed. Mona Etienne and Eleanor Leacock (New York: Praeger, 1982); Carol Devens, Countering Colonization: Native American Women and Great Lakes Missions, 1630-1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992); Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001).

- Jose Antonio Brandão, `Your fyre shall burn no more’: Iroquois policy toward New France and its Native allies to 1701 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997); D.K. Richter, “War and Culture: the Iroquois Experience,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd. Ser., Vol. 40, No. 4. (Oct., 1983), 528-559.

- Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes region, 1650-1815 (Cambridge: New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

- John Dickinson, “Native Sovereignty and French Justice in Early Canada,” in Crime and Criminal Justice in Canadian History: Essays in the History of Canadian Law, Vol. V, ed. Jim Phillips, Tina Loo and Susan Lewthwaite, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 1994); Cornelius.J. Jaenen, “French Sovereignty and Native Nationhood during the French Régime,” in Sweet Promises: A Reader on Indian-White Relations in Canada, ed. J.R. Miller (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 19-42.

- Daniel Richter, Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America (Cambridge: Harvard, 2001).

- Native peoples’ demand for both manufactured goods and firearms increased as Europeans and their goods became more plentiful in North America. See Richter, Facing East, 41-53.

- I also assign Allan Greer’s compilation, The Jesuit Relations.

- While Diefendorf’s work focuses on the young men and women who joined confessional orders, the young Father Laforgue’s abandonment of marriage, the family estate, and the physical presence of his mother fits his case well within the phenomenon Diefendorf describes. See Barbara Diefendorf, “Give Us Back Our Children: Patriarchal Authority and Parental Consent to Religious Vocations in Early Counter-Reformation France,” The Journal of Modern History 68:2 (1996), 265-307.

- Craig Harline and Eddy Put, A Bishop’s Tale: Mathius Hovius Among His Flock in Seventeenth-Century Flanders (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002).

- See Jane Freebury, “Black Robe: Ideological Cloak and Dagger?” Australian-Canadian Studies 10/1(1992), 119-126. Freebury has criticized Beresford for reinforcing the classic trope of the lone hero found in Hollywood Western, but I think it is also possible to argue that the lone figure celebrated in Hollywood Westerns can also be found in the heroic narratives of Jesuit tradition.

- Greer, The Jesuit Relations, 157-171.

- Allan Greer, “A Wandering Jesuit in Europe and America,” in Linda Gregerson and Susan Juster, eds., Empires of God: Religious Encounters in the Early Modern Atlantic (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 106-122.

- In his autobiography and letters, Loyola warned against the kind of excessive fasting and self-flagellation that he had practiced early in his career, activities that he came to believe had ruined his own health. See, for example, Joseph N. Tylenda, S.J., ed., Counsels for Jesuits: Selected Letters and Instructions of St. Ignatius Loyola (Chicago: Loyola Press, 1985).

- Medieval Internet Sourcebook, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1543xavier1.asp and http://www.fordham.eduhalsall/mod/1549xavier2.asp.

Cecilia, Amanda and Laurie: Thanks for this wonderful forum (and to Liana for commissioning it)! I also teach Black Robe with Allan Greer’s edition of the Jesuit Relations, in a course on early modern travel and contact. I’ll have to look at the Churchill and Axtell pieces next time I teach the class. I appreciate your different analyses of the film’s strengths and weaknesses and your discussions of the different contexts in which you teach it. One additional thing the film does for me, when paired with the Jesuit Relations, is to help students think theoretically about the comparative benefits of text and image as pedagogical tools, and also the process of how historical films are made. They are surprised when they realize that the filmmakers have also read the Jesuit Relations; for them, it is fascinating to guess which scenes are drawn from which récits, and to see where the film departs from text. Thanks for revisiting this classic: those of us who have taught it many times can always use fresh food for thought to enliven future showings!