Nathan Marvin, University of Arkansas at Little Rock

“Slavery and Freedom: Journeys Across Time and Space” opened in May 2024 at UA Little Rock Downtown, a community engagement center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. It features thirty-six panels that bring together the stories of two nineteenth-century freedom suits from different parts of the world. The suits were brought by Furcy Madeleine on Réunion Island, whose story and exhibit are detailed elsewhere in this issue, and Abby Guy (born circa 1811), who after years of de facto independence in Arkansas, was abruptly re-enslaved with her children. Guy launched a freedom suit against her enslaver, William Daniel, in 1855. It reached the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1857 and again in 1861. Against all odds, Abby Guy and Furcy were ultimately successful in securing their status as legally free persons.

This exhibit was made possible through a partnership between UA Little Rock and the Musée historique de Villèle on Réunion Island, the latter of which offered a traveling version in translation of their “Strange Story of Furcy Madeleine.” This joint endeavor was conceived in 2022 at the French Colonial Historical Society conference in Charleston, S.C., during a meeting that involved myself, Sue Peabody (historical consultant on the original French exhibit), Jean Barbier (then director of the Musée de Villèle), and Jérémy Boutier, curator and historical consultant for the Musée de Villèle. We met again the following January at UT Austin for a special roundtable on “Representing Slavery in Museums: The French World,” hosted by Dr. Mélanie Lamotte (now at Duke University). Energized, Jérémy and I traveled by rental car to Little Rock, stopping at Buc-ees Country Stores and listening to Charley Pride, to meet with Marta Cieslak, director of UA Little Rock Downtown. She was as excited as we were about the prospect of an international partnership, so we began mapping the space and discussing how to build on the Réunion exhibit.

We settled on a wide-ranging exploration of the history of slavery and emancipation from two unlikely vantage points: the French overseas département of Réunion Island in the western Indian Ocean, and the state of Arkansas in the American South. Both places contain only one percent of their respective countries’ population but both, as well, were significant sites of plantation slavery in the nineteenth century. Arkansas played a key role in the cotton boom of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Réunion gained economic importance as a major sugar producer for the French empire in the wake of Haitian Independence. There was another unlikely connection too: slavery in both spaces first developed under the same legal system. The Lettres Patentes du Roy of 1723, which adapted the Caribbean Code Noir for the Bourbon islands and neighboring Isle de France, were promulgated in the fledgling French colony of Louisiana, which encompassed the settlements of today’s Arkansas, in 1724. These two locations, long marginalized in popular accounts of slavery and resistance, lent themselves well to a comparative exploration of their histories and legacies

Mounting the Exhibit in Arkansas

We sought and received financial support for the project from the Arkansas Humanities Council, a partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. To align with the AHC’s goal of enhancing understanding of Arkansas history and culture, we designed our application to connect the “Furcy” exhibit with Arkansas history and engage local institutions. It was in reaching out to one of those institutions, UA Little Rock’s Bowen Law School, that we recognized an extraordinary opportunity to integrate the case of Abby Guy, the original files from which were held in the law library’s archives. Despite the historical significance of that case, it had, to our knowledge, never been featured in a public history project.

We involved students from the very beginning of the process, offering undergraduate majors and Masters’ students in our Public History program hands-on experience in creating a historical exhibit. As faculty at UA Little Rock, I led a mixed seminar in Fall 2023 titled Global Perspectives on Race. Students compared the suits of Furcy Madeleine and Abby Guy and participated in virtual meetings with Jérémy Boutier and Sue Peabody, learning from their experience crafting an exhibit and discussing how we might elaborate our own historical narrative. The students worked in teams, each of which focused on a different component: narrative sections, images, maps, and timeline. They became genealogists who reconstructed Abby’s family tree; photographers who documented the sites and landscapes where she lived and worked; and, during a field trip to the Bowen Law Library, experts in manuscript transcription, when Melissa Serfass, Professor of Law Librarianship, invited us to view the original transcript from the trial. That moment, when we were given the chance to hold Abby Guy’s 1855 petition—the instrument of her self-liberation—in our hands, was perhaps the most meaningful of the semester for us all.

It was immediately clear to us that placing the Abby Guy case alongside Furcy’s revealed how power in slave societies was maintained and contested on similar grounds, even in vastly different regions that were half a world apart. The juxtaposition also created the opportunity for a more critical representation of race that challenged simplistic generalizations about slave societies and supposedly clear-cut axes of distinction between black and white, slave and free. The ambiguous statuses of Abby and Furcy, who could not be readily categorized, highlighted the fragility of their respective racial systems; their situations needed to be clarified by the courts because, as historian Ariela Gross reminds us, “the margins of a category create the core.”[1]

In litigating their identities, both Abby and Furcy asserted non-African parentage, reinforcing an emerging hierarchy of origins that equated enslaveability with people from the African continent. Furcy’s legal victory ultimately rested on a “free soil” argument (like the one that failed in the landmark Dred Scott case in the United States), but he also pursued several defenses based on race. He argued that his father’s European origin made him “a French citizen.” Furcy’s lawyers did not, however, argue that he was “white,” despite the breadth of that category on Réunion, which included many people whose ancestors had come from Madagascar and South Asia. (Notably, one of the lawyers, who came from a prominent white family, was himself accused of having distant Malagasy heritage during the trial).[2] Instead, Furcy’s lawyers cited his mother’s birth in India as a defense against his continued enslavement, despite the longstanding presence of South Asian slaves on Réunion Island.[3]

Abby, on the other hand, although categorized as “mulatto” on the 1850 census, claimed to have descended from exclusively European stock. She argued that her mother had been a white orphan kidnapped into slavery in Virginia. Witnesses familiar with the family testified that Abby’s mother had certainly been enslaved and had been of “dark color,” though they could not confirm whether she was “of African or [American] Indian extraction.” Abby’s lawyers were determined that the jury not believe the former claim. By putting the bodies of Abby and her children on display in the courtroom, they hoped to demonstrate that whatever “hidden” traits experts claimed could reveal African ancestry (like the shape of a foot) were not readily observable. Ultimately, a jury of white, mostly slave-owning men ruled in favor of Abby’s right to continue living as a free woman, which lent credence to the idea that whiteness was not just tied to appearance or some innate quality of blood. Later, the judges of the Arkansas Supreme Court who reviewed the case suggested that jurors had turned a blind eye to the evidence because they feared the possibility of mistakenly enslaving persons understood to be white. Moreover, had they not found in Abby’s favor, it would have implied that white Arkansans like them, and like Abby’s neighbors, were unable to distinguish between white and Black people.

Furcy and Abby’s protracted lawsuits became turning points in the divergent historical developments of their respective contexts. Furcy’s case became a cause célèbre in Paris, covered by city newspapers, gaining the attention (and monetary support) of the queen, and possibly tipping the scales of public opinion further toward abolition. In contrast, while antebellum Arkansas juries twice vindicated Abby Guy (and higher courts affirmed these decisions on appeal), her case prompted the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1857 to devise what was perhaps the most restrictive legal definition of whiteness in the country—the first of the “one-drop” rules that would become so consequential later in the Jim Crow South. Then, in 1859, the state legislature passed an outright ban on free people of African descent. Had a jury of white slaveholding men not essentially found her to be “white,” Abby would have become persona non grata in the state. Slavery itself, of course, remained legal in Arkansas until after the Civil War.

Ultimately, the students found the personal stories of courage and hard-won legal victories to be the most compelling throughline between the Furcy and Abby cases. The stakes were extraordinarily high: freedom or enslavement, the right to marry who one chose, the ability to own property, a future of dignity and possibilities for one’s children. Accordingly, the students conceived an exhibit that centered on Abby—her experiences, choices, and itineraries—and helped me see the centrality of space in her story. We knew Abby had been granted de facto freedom by her enslaver, but it was only by mapping her movements that we could fully understand how she thrived and fashioned a new identity for herself. Settling in the frontier zone that linked southeast Arkansas to Louisiana was vital. This area had long been a haven for people fleeing slavery as well as for squatters from the eastern states, like James Guy, the man with whom Abby would come to live. As one student noted, it was there that she carved out a life of independence and dignity by exercising the bodily autonomy denied to her under slavery. Abby also engaged in the ‘production of white womanhood’ by managing her deceased partner’s land, entering into business contracts, enrolling her daughters in boarding school, and participating in the social life of her church. This aggressive self-fashioning paid dividends: she successfully recruited white allies from her community to testify on her behalf when she was forced to go to court to protect her freedom.

The students’ approach to narrating Abby’s story was strongly influenced by our reading list. Discussing Stephanie Camp’s notion of “rival geographies” and its application across various studies of slavery and resistance provided language for the role of space in Abby’s story.[4] Black feminist analyses of race and gender provided an additional theoretical framework for interpreting Abby’s actions and limitations.[5] We also examined the latest ethical standards in digital humanities projects on slavery, focusing on the authentic and responsible presentation of historical language,[6] creating data visualizations that enhance understanding while minimizing harm,[7] and ensuring our presentation did not inadvertently reproduce the violent assumptions that underpinned systems of racialized slavery.[8] Ultimately, we set aside most academic language in favor of a clear, accessible narrative, but the concepts and principles we studied inspired the design and key points of the exhibit that was eventually produced.

Adaptation for Local Audiences

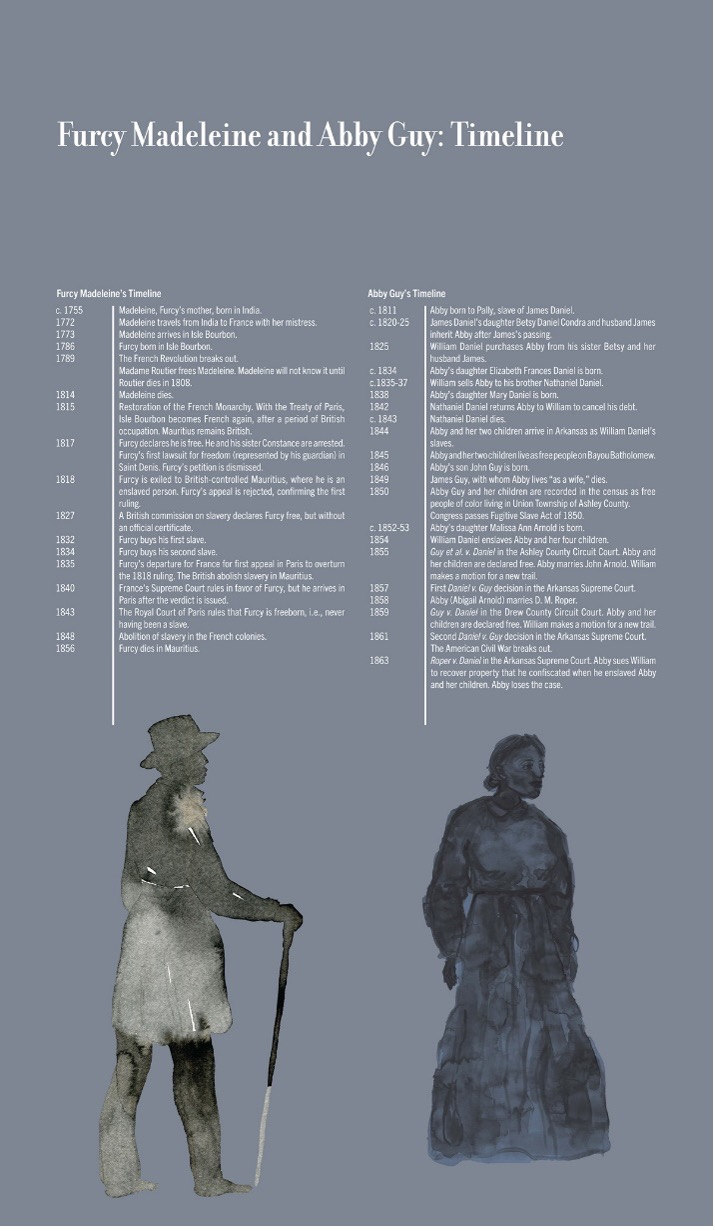

In producing the portion of the exhibit on Abby Guy, the team at UA Little Rock Downtown—Marta Cieslak (Director), Emily Housdan (Programming and Administrative Assistant), and Jess Porter (Director, UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture)—expanded on the students’ broad conceptualization to create a comprehensive exhibit. They conducted meticulous detective work of their own and integrated new findings from the archives. To bridge the Furcy exhibit with the Arkansas material, they created a new timeline panel that merged the exhibits by incorporating events from both lives on a single pane.

We wanted the exhibit to remain in conversation with Furcy’s but also to stand on its own as a microhistory that helped visitors understand the social and legal dimensions of slavery and freedom in nineteenth-century Arkansas.

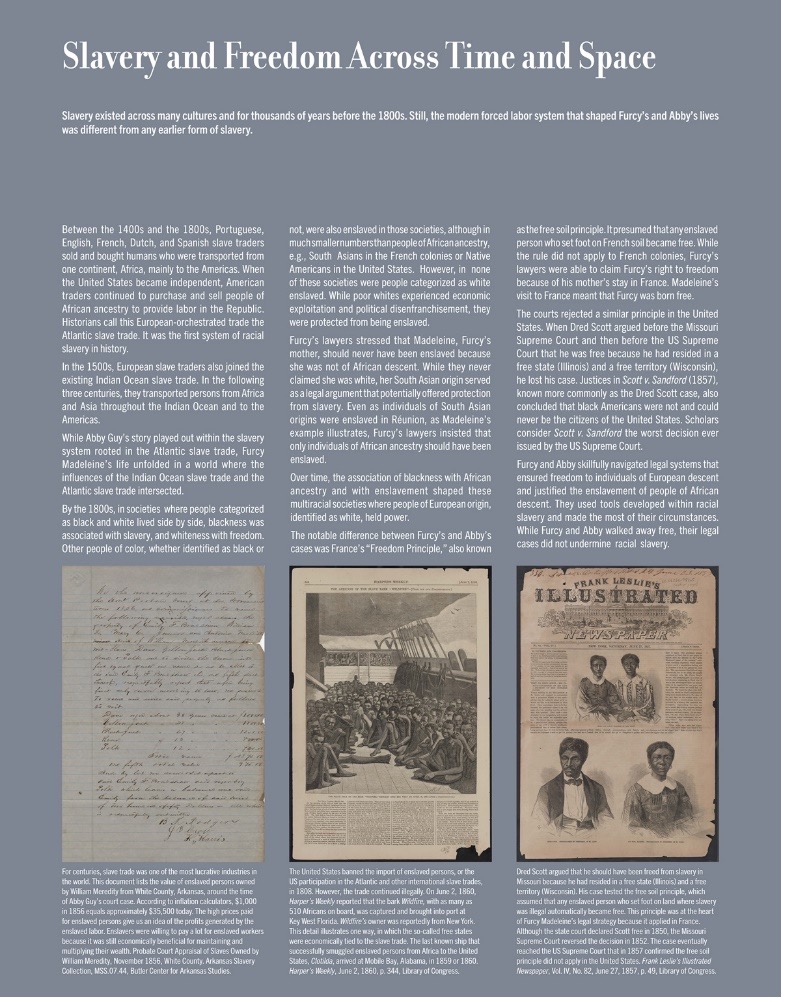

A concluding panel was added to introduce the wider world of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades and to compare the lawsuits, highlighting what they revealed about the changing social and legal understandings of race.

Recognizing the complexity and sensitivity of vocabulary related to race and gender, we opted for straightforward, accessible language. We followed the standards set by the translators of the Furcy panels, retaining the terms “black” and “white” to emphasize the binary system that operated in both contexts. Additionally, we preserved the original language for labels describing persons or communities that did not fit neatly into this binary, as they appeared in the historical record (e.g., “malbar” / South Asian in the Furcy exhibit; “mulatto,” in quotations, in the Abby Guy exhibit). We made no assertions about Abby Guy’s “true” racial background, instead laying out the facts to emphasize that race was as much imposed as it was claimed and performed, ultimately a social and legal construction.

The word “gender” does not appear in the main texts of any of the panels, but explanations of the gendered dimensions of the cases are everywhere in the exhibit. Gender is key to understanding the connections between the Furcy and Abby stories. It played a crucial role in arguments for and against the Réunion and Arkansas cases, because slavery was heritable matrilineally according to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem. For that reason, both trials focused heavily on the status of the plaintiffs’ mothers. Even the silences in these cases are gendered. While the identity of both plaintiffs’ fathers was an open secret, propriety kept it from being mentioned in court. To communicate these points effectively, we chose accessible language and avoided terms that might be read as overly academic or misconstrued as political. Over the course of their lives, both Abby and Furcy adopted surnames (a privilege reserved for free persons) according to different gendered conventions. Furcy adopted his mother’s given name, Madeleine, per local tradition.[9] Abby’s last name, on the other hand, was that of James Guy, the white man with whom she lived “as his wife.” It is a reminder of the patriarchal mechanism that allowed women of non-European descent and even former slave status to access social whiteness and its protections, what the Furcy exhibit called “Whitening by Marriage.” As one author has noted, Abby’s former master, William Daniel, “never made a claim on [her] as long as James Guy was alive.”[10]

Violence was a defining feature of Abby’s story, and we were mindful of our responsibility to present it in a respectful, straightforward way. We found it particularly important to include documentary evidence, given the lingering misconception that Arkansas was peripheral to the most dehumanizing practices of chattel slavery in the American South. We also tried to avoid adopting an overly moralizing tone. Like the team behind the Furcy exhibit, we were clear that Abby’s fight—although extremely courageous—was not against slavery as an institution or racial hierarchy. In fact, as we emphasize, it was only by winning recognition as a white woman that Abby could secure permanent freedom for herself and her family.

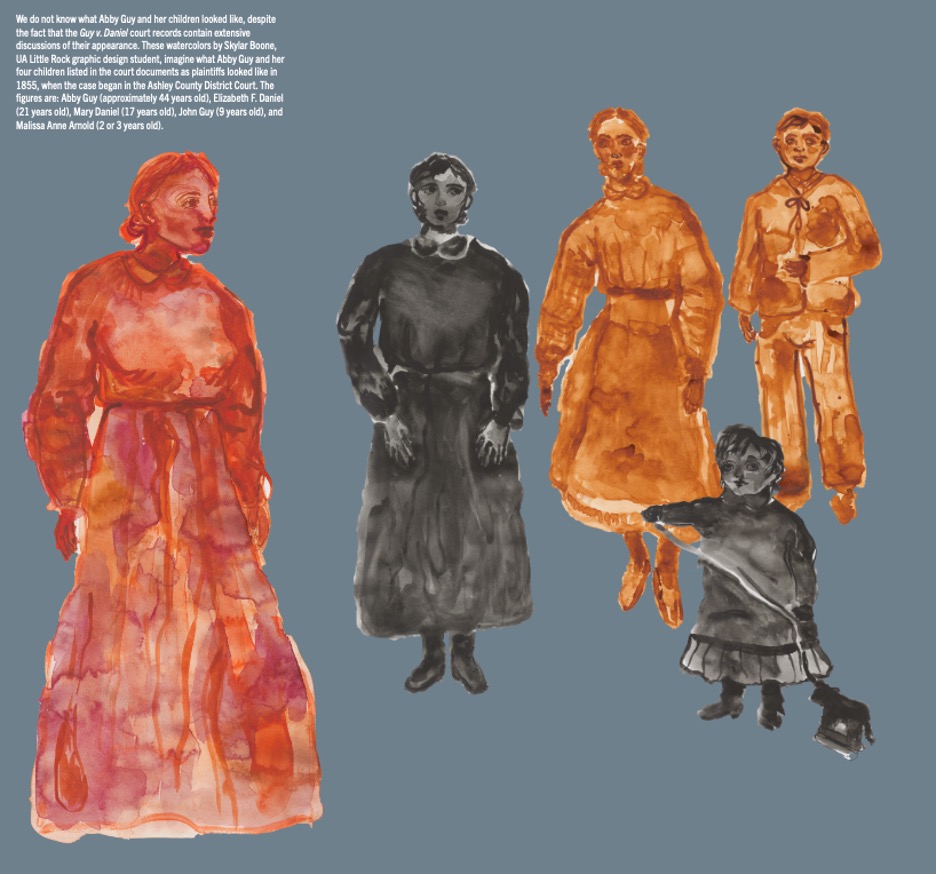

Another way we sought to immerse visitors in these stories was through the exhibit’s visuals. Photographs of archival documents form the visual foundation of both Furcy and Abby Guy panels. Like the “Furcy” exhibit, the Abby Guy exhibit focuses on the central figure revealed through the legal documents she produced and preserved. These documents, often the key to freedom, were among the few opportunities we had to directly “hear” the voices of Abby Guy and Furcy Madeleine. By acknowledging the many open questions and unknowns that remain—gaps in the paper trail—rather than trying to fill in the blanks, we allowed visitors to reflect on the fragmentary traces of Abby and her children, fill in the silences themselves, and let the story resonate in a more meaningful and personal way.

Skylar Boone, a graphic design student from the School of Art and Design at UA Little Rock, was selected from multiple applicants to create watercolor paintings for the exhibition. Her imaginative representations of Abby Guy, her enslaver, and her children maintain a strong focus on the dramatis personae, much like Sébastien Sailly’s watercolors for the original Furcy exhibit. Boone’s figures harmonize aesthetically with the Furcy watercolors, creating a cohesive visual experience for visitors as they move between sections from Arkansas to the Indian Ocean and back again. Her watercolor of Abby, placed atop an image of the petition Abby authored in 1855 to launch her quest for legal freedom, serves as the background for the exhibit’s promotional materials, complementing the designs from the original Furcy exhibit.

Reception and Future Directions

The exhibit has garnered significant community interest. It has been featured in the local newspaper of record and highlighted in a television interview on the city’s CBS affiliate. Guests have visited from across the United States, including North Carolina, Illinois, and Missouri, as well as internationally, from countries such as South Africa, the Czech Republic, and Great Britain. Among our most enthusiastic visitors was a mother-daughter duo originally from Paris, now living in Conway, Arkansas (about 55 km from Little Rock). As they reflected on their personal connections between Arkansas and France, they were particularly thrilled to see a chapter of French history on display in Little Rock.

Perhaps our most memorable visit was from Reverend Deborah Senter and her GED class from Shorter College, a historically Black two-year college in the Little Rock area. Rev. Senter and her students read each exhibit panel aloud and discussed the content as a group. The students drew fascinating connections between past and present, finding aspects of their own experiences reflected in the stories of Abby Guy and Furcy Madeleine. They were especially passionate about the idea that Abby and Furcy both fought to define their own racial identity, refusing to accept how others wanted to define it.

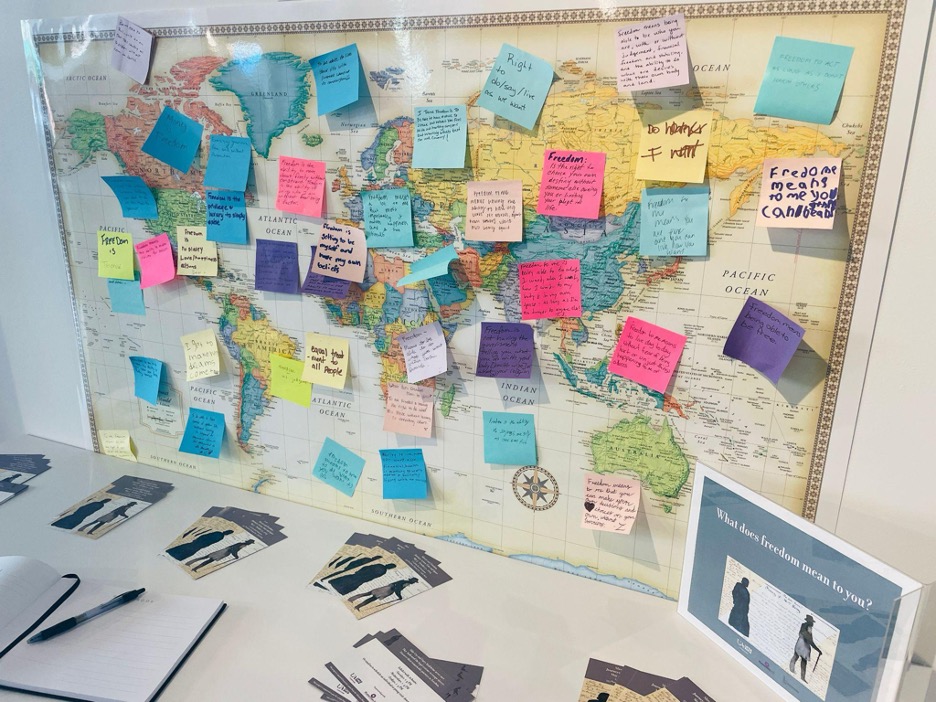

We have invited all guests to reflect on the question, “What does freedom mean to you?” and to leave their thoughts on a bulletin board set up amidst the exhibit panels. Many shared their responses. One that particularly stuck with us came from one of our youngest visitors, who wrote simply, “It means I get to make my dreams come true.”

Watching this exhibit grow from a conversation to a reality was a dream come true for me, as it was for many students who saw their ideas and contributions reflected in the final product. One student, John Morris, interviewed for a segment about the exhibit on a local TV station, remarked that as a Master’s student, he was used to engaging with scholarly sources and producing academic work, but “this will be viewed by a general audience.” It was deeply rewarding, he said, to be able to “contribute to such an amazing story.” I share that sentiment. Whenever I discuss the project with people from Arkansas, their enthusiasm is palpable. Here is a compelling local story with historical significance that resonates far beyond the state. Like John, I’m proud to have played a role in making it accessible to a greater number of people.

It has also been exciting to see the venue itself flourish under the stewardship of Marta Cieslak and Jess Porter (Director of the UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture, of which UA Little Rock Downtown is a part). Their curatorial initiatives include connecting Arkansas to the wider world and highlighting the histories and experiences of groups in the region that have not always been prioritized in programming, events, and archive acquisitions. They have made strides to preserve and promote the histories of Black, Asian, and Hispanic communities, as well as queer Arkansans. “Slavery and Freedom” closely aligns with these institutions’ mission of uplifting marginalized groups. Collaboration with other cultural institutions in the Downtown area has also been integral to this mission. The venue has become more than just an extension of the university; it has become a hub for education, public service, community engagement, and now, an exhibit space, fostering a more meaningful sense of place in our city.

Little Rock is only the first stop on the Furcy exhibit’s journey across the U.S. The current run is scheduled to end on October 31, after which the exhibit will find a new home in the History Department at Duke University in Durham, N.C., starting in January 2025. Then “Furcy” will continue northward to the University of Virginia’s Shannon Library. Our grant terms stipulate panel recycling as a strategy for managing costs and ensuring greater sustainability, and we are proud to report that the prints and display apparatuses will be reused at the next stop on the exhibit’s journey. Expanding the exhibit to more locations, some with integrated local case studies, will present rewarding opportunities for U.S. institutions to engage faculty, students, and communities in exploring the thought-provoking case of Furcy Madeleine. As for Abby Guy, her story, like Furcy’s, will also be translated for a new audience. Jérémy Boutier and I have been invited to produce a French-language version of “Slavery and Freedom” for display at the Musée de Villèle, in time for Réunion’s December 20 holiday commemorating the anniversary of the abolition of slavery in 1848.

[1] Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 11.

[2] Nathan Marvin, “‘Free and Naturalized Frenchwomen’: Gender and the Politics of Race on Revolution-Era Bourbon Island,” in Fertility, Family, and Social Welfare between France and Empire: The Colonial Politics of Population, ed. Margaret Cook Andersen and Melissa K. Byrnes (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 59–87; Jérémy Boutier, “L’ordre Public: Sully Brunet et Les Contradictions de La Justice et de La Politique Dans l’Affaire Furcy (Ile Bourbon, 1817-1818),” French Colonial History 15 (2014): 135–63.

[3] Sue Peabody, Madeleine’s Children: Family, Freedom, Secrets, and Lies in France’s Indian Ocean Colonies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 65, 119–20.

[4] Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 7; Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

[5] In early panel drafts, students cited Stephanie M. H. Camp, “The Pleasures of Resistance: Enslaved Women and Body Politics in the Plantation South, 1830-1861,” The Journal of Southern History 68, no. 3 (August 2002): 533-572; Jennifer L. Morgan, “Partus Sequitur Ventrem,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 22, no. 1 (March 1, 2018): 1–17.

[6] “Statement of Principles,” Colored Conventions Project, https://coloredconventions.org/about/principles/; “Oceans of Kinfolk,” Kinfolkology, https://www.kinfolkology.org/oceansofkinfolk, accessed August 20, 2024.

[7] Katherine Hepworth and Christopher Church, “Racism in the Machine: Visualization Ethics in Digital Humanities Projects,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 12, no. 4 (February 4, 2019).

[8] Jessica Marie Johnson, “Markup Bodies: Black [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads,” Social Text 36, no. 4 (December 1, 2018): 57–79.

[9] Sue Peabody, “Les enfants de Madeleine, esclaves à l’île Bourbon (XVIIIe-XIXe siècle),” Clio: Femmes, Genre, Histoire, no. 45 (Spring 2017): 171-84. English translation appeared in 2020 online at Clio: Women, Gender, History, accessed August 20, 2024, https://journals.openedition.org/cliowgh/.

[10] Russell Mahan, Abby Guy: Race and Slavery on Trial in an 1855 Southern Court (Santa Clara: Historical Enterprises, 2017), ch. 3.