Elodie Silberstein, Pace University

Ady, soleil noir (Philippe Rey, 2021) traces the love story between American artist Emmanuel Radnitzky (1890-1976), better known as Man Ray, and his model Ady (born Adrienne) Fidelin (1915-2004) in the effervescence of 1930s Paris. In so doing, this compelling historical novel offers us the rare portrait of a woman of color during the interwar period.

From the early pages of the book, Guadeloupean writer Gisèle Pineau evocatively sets the scene of Paris as the new Babylon. (12-27) Forgotten are the horrors of World War One and the privations of the Great Depression. Let’s live fully in the present without thinking too much of the future. In locations from the Antilles to the African continent, Parisians search for escapism in fifty shades of blackness. The public cannot get enough of the sparkle of American born dancer and actress Josephine Baker. Caribbean cabarets are popping up all over the city like mushrooms after the rain. Black and white, bankers and factory workers, everybody mingles in the adrenalized ambience of the bal Blomet—as of course, do avant-garde artists such as Man Ray.

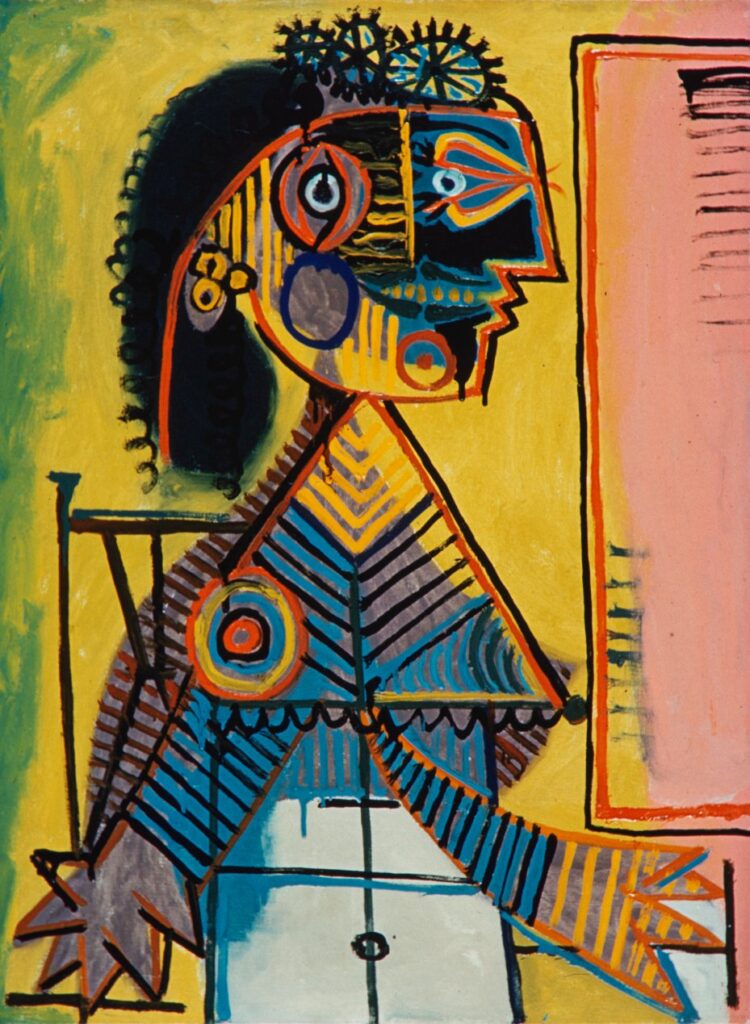

Ady is a Guadeloupean professional dancer with a head full of dreams. She braves the bitterly glacial weather of Paris to dance at the bal Blomet and flirt to the tempo of the biguine music as if there is no tomorrow. She is 19 years old when she meets Ray, who invites her to dance with him, pose for him, and share his life. He is 46, already successful as an artist and disillusioned as a lover who has promised himself not to fall for another woman. (6) Then he crosses Ady’s path, and she becomes his “little black sun.” (9) There follow five years of shared happiness and complicity—drinking wine while remaking the world, dressing-up for masked balls, enjoying picnics in bucolic landscapes, making love, spending time in country houses, swimming naked in the sea, and going to art openings. We follow Ady’s immersion in the world of modern art. She introduces us to Pablo Picasso, Dora Maar, Constantin Brâncuși, Frida Kahlo, and Lee Miller, to name just a few. The book is filled with bubbling vignettes of the life of avant-garde artists in Montparnasse and the South of France.

Step by step, we discover the story behind Ady’s craving for hedonism. The trauma of losing her mother during the apocalyptic hurricane that devastated Guadeloupe in 1928, and then of losing her father, who was consumed by grief, two years later. Orphaned at the age of fifteen, Ady is taken in by her older sister Raymonde. (53) The flat of Raymonde and her husband Narcisse, nested in the Paris region, would be the perfect setting to raise a proper young woman, would it not? A new chapter of Ady’s life begins with a past she is keen to both forget and commemorate. It is this sweet-sour taste of the paradis perdu (lost paradise) (105) of her childhood that Ady seeks as she pursues creativity, leisure, and frivolousness with Ray and his artistic friends from the surrealist movement.

The atrocities of World War Two drive Ady and Ray back to a reality they have been eager to dismiss. Ray is Jewish. In 1940, he is forced to return abruptly to the United States to flee the Nazi occupation in France. (199) Ady stays behind with her family. At that moment, we come to understand that the fabric of the story is Ady’s idyllic interlude between two traumatic wounds: losing her parents in Guadeloupe and losing the love of her life when war strikes again. This time, she writes the second story of loss, which will leave her scarred forever.

Pineau blends fiction and reality to encapsulate the lighthearted spirit of the capital and the subsequent anguish of occupation. In 2021, she won the Prix du roman historique, a well-deserved acknowledgement of her descriptive prose, which always pays attention to the intricacies of the international historical context. Pineau takes her time to craft her text, carefully detailing interwar life. Her play with words makes this travel through time a pleasure.

What I find most valuable in Pineau’s book is her giving of voice to Ady. Ady Fidelin died on February 5, 2004 in complete anonymity. She was a professional dancer, the first Black model to be featured in the fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar (1937), and an active participant in the cultural life of the surrealist circle. And yet, despite her accomplished life, Ady’s contribution to art history received scant attention. Even statements about her country of origin were inaccurate. She was presumed to have been from Martinique, the Philippines, or Haiti.1 We had to wait for the lengthy investigations of historian Wendy A Grossman to learn the extent of Ady’s influence on artists like Pablo Picasso, for whom she modeled in 1937 as the Femme assise sur fond jaune et rose, II.2

Pineau’s novel counters the erasure of people of color like Ady. She follows the path traced by scholars like Denise Murrell, who are uncovering the excluded stories of Black models in Western art. In 2018, Murrell curated Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today. This groundbreaking exhibition first opened at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery (New York) before being presented in an expanded version at the Musée d’Orsay (Paris) as Le Modèle Noir de Géricault à Matisse (The Black Model from Géricault to Matisse). Taking Édouard Manet’s painting Olympia (1863) as a point of departure, Murrell highlights how Black models played pivotal roles in the development of modern art. While scholars have written in abundance about Manet’s brazen and controversial depiction of the nude courtesan, there is an astonishing silence about the Black servant holding Olympia’s flowers: Laure. Murrell pinpoints such academic and institutional blind spots by restoring the names of models whose identities had been lost or were never recorded in the archives. She tracks down the story of Laure, who lived in Manet’s socially and ethnically diverse neighborhood of Northen Paris.3 Her research recovers, as well, the names of the hitherto anonymous figures of Henri Matisse’s drawings—Catherine Raymonde Dubois and Carmen Lahens—and their rich lives.4

Pineau parts company with Murrell regarding the latter’s rejection of the denigrating sexualized trope of the “Black Venus” that characterized canons of the day. Murrell is critical of the sexual undertones of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s life-sized bust of a captive young woman La négresse ou Pourquoi naître esclave? (Black woman or Why born a slave?) (1872).5 One of her key arguments is that Black models have never been passive muses, but active collaborators in their portrayals. When Murrell brings our attention to the little-known Manet portrait of Laure, La négresse (re-titled Portrait of Laure) (1863), it is to point out that she is “a subject in her own right” of the painting.6 Laure stands against a neutral background that magnifies her presence. She is the focal point of our attention. Her gentle smile, composed attitude, white blouse and discreet jewelry frame her as a reserved beautiful woman with little suggestion of sexual availability. Here, Manet did not capture Laure as an exotic “other” but “as part of the working class of Paris”.7 After the second abolition of slavery in 1848, Paris had become home to a growing presence of free Black people who not only participated in everyday life but wrote the story of French modernity.

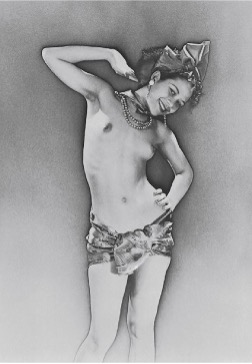

Pineau’s novel seems far from Murrell’s challenge of colonial fantasies of passivity and lasciviousness. The first image of Ady that readers encounter is a reproduction of Ray’s photograph taken in 1937. (8) Otherwise naked, Ady is dressed only in a loincloth with a pink ribbon in her hair, her nudity and exotified head wrap following well established Orientalist pictorial conventions. I think for example of the depiction of the Black servant in Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting Moorish Bath (1870). Ady’s nostalgic recollection of the photo shoot, which immediately follows Ray’s photograph, corroborates this impression of availability. An older Ady remembers Ray looking at her younger self, nue, café au lait, sucrée (naked, coffee with milk, sweet), joyful, and même pas gênée (not even embarrassed) to reveal her body. (9) Ady’s emphasis on her willingness to pose “at [Ray’s] request” (à sa demande) in stereotypical attire, positions her as a compliant, exotic muse serving the male “genius”—an image full of sexist and racist undertones (9). Indeed, Pinault’s depiction of Ady’s unconditional love for Ray throughout the novel can be frustrating, as when she appears unfazed while reading later in life about Ray’s muses only to find that her name is missing: Kiki de Montparnasse, Lee Miller, or Juliet Browner… “I am not bitter,” she claims, “just erased from history like a piece of furniture in the background.” (90)

Ady’s acceptance of her fate is especially challenging to read because the historical erasure is mirrored in her personal life. For Ray, while being deeply fond of Ady, seems never to have appreciated her as she deserved. Indeed, as Grossman and Patterson note, he naturalized Ady’s subordination in their relationship.8 In a letter to his friend Roland Penrose, for example, Ray delights in Ady’s energy, which cheered him up, and praises her for doing everything around the house, from shining his shoes to bringing his breakfast. Nor did her dedication end with their relationship. She protected Ray’s legacy by safeguarding his artworks and personal effects during World War Two.9

Still, I would argue that the novel’s limitations are also its strength. The book has the potential to foster important conversations about the contemporary meanings of Blackness and its politics. The debate is still a sensitive, topical issue that promises rich exchange in a classroom. Consider the recent controversy around Beyonce Giselle Knowles-Carter. When on November 25, 2023 the pop star singer attended the premiere of her film Renaissance in a sparkling silver dress and platinum blond wig, social media accused her of lightening her skin and hair to appear whiter. Pineau’s book reminds us that Black people are not a monolithic group. There is a plurality of walks of life, politics, histories, aspirations, and social positions. “What does that mean the soul of Black folk?” Ady asks when challenged by students at the Sorbonne University to follow the principles of African American civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois. (77) Ady is Black. And she is also a woman with her own painful wounds, ambitions, fears, and doubts. The interest of Pineau’s prose is to capture her complexity.

We follow Ady’s struggle to negotiate her multilayered identities and find her place as a French woman of Caribbean heritage. Always lingering is the painful feeling of being an exile in her own country. Ady’s trajectory exemplifies the love-hate relationship that people of African descent can feel for a country synonymous with slavery, spoliation, and discrimination. (37) In the early twentieth century, expressions of racism—from derogatory caricatures of savage and primitive Black men in popular culture to the paternalist civilizing tone of the so-called antiracist discourse—were still woven into the social fabric. (77-78) Even so, Ady does not feel close to Négritude thinkers, a network of Black intellectuals who resisted the Eurocentric status quo by advocating for a Black consciousness across the Afro-diasporic panorama. She feels as far from these elitist forms of racial politics as she does from the pressure of her family’s expectations. She longs to please her conservative siblings, who endorse models of modest femininity, while at the same time embracing (if not capitalizing on) her “Black Venus” aura. Did not Josephine Baker advise the Black community to indulge white people with images of exoticism so that white people could be less scared of their Blackness? (171)10 Ady seems to feel much closer to the superficial approach of her surrealist group. Even if the price is playing an enslaved woman with a fake chain around the neck (19). Even if her family and acquaintances denigrate her choice to play poupées noires (Black dolls) and accuse her of bringing shame on them. (74) After all, as Ady reminds us, the Black men who so harshly criticize her were keen to date poupées blanches (white dolls) without anyone raising an eyebrow. (74)

The novel offers a rare insight into the journey of a Black woman trying to negotiate competing expectations. By doing so, it raises important questions about axes of race, class, and gender. One could ask on what ground anyone has the right to chastise women who embrace a fantasized, eroticized version of Blackness. Scholar Mireille Miller-Young addresses just this point in her corpus on modes of representing Black actresses in X-rated films. I could not help thinking of Ady’s admiration for Josephine Baker when Miller-Young introduces us to actress Jeannie Pepper, a porn star who, while shooting in Paris in 1986, envisioned herself as Baker, “admired in a strange new city for her beauty, class, and grace.”11 Miller-Young highlights how performers like Pepper are marginalized from the Black community for perpetuating harmful stereotypes of the allegedly hypersexual Black women, but she also makes a case for the importance of recognizing performative labor as acts of resistance that position women like Pepper as desired and desiring subjects.

Most importantly, one could ask if it is fair to expect any Black woman to represent an entire racial group. Must Black women always stand up against their oppression, even at the expense of their own aspirations? When Peggy McIntosh listed forty-six examples of white privilege in her 1988 working paper, “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies”, she included: “I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group”.

Pineau’s book does not attempt to answer directly any of these interrogations, opening more questions than she resolves. And that is just as well, to encourage conversation and self-reflection.

Bibliography

Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018).

Mireille Miller-Young, A Taste for Brown Sugar: Black Women in Pornography (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014)

Peggy McIntosh, “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies,” Working Paper 189, Wellesley Centers for Women (1988).

Wendy A Grossman, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Adrienne Fidelin, a Quest for Rediscovery,” Restoration Conversations 3 (Spring/Summer 2023):60-67.

Wendy A Grossman and Sala E. Patterson, “Adrienne Fidelin,’’ in Cécile Debray et al. ed., Le Modèle Noir de Géricault à Matisse (Paris: Flammarion, 2019), pp. 306-311.

Notes

- Grossman and Patterson, 306. ↩︎

- Grossman, 61. ↩︎

- Murrell, 9. ↩︎

- Murell, 176-179. ↩︎

- Murrell, 43. ↩︎

- Murrell, 7. ↩︎

- Murrell, 43. ↩︎

- Grossman and Patterson, 306. ↩︎

- Grossman and Patterson, 310. ↩︎

- Baker incarnated a model of perfect Blackness. But would French people have been as appreciative of her immense talent and courage if she had vigorously stood up against the French colonial empire? Instead, Baker’s participation in the civil rights movement was quite comforting for a nationalistic France keen to be perceived as morally superior and more progressive than the United States. ↩︎

- Miller-Young, 3. ↩︎