Corine Labridy in conversation with Sophie Saint-Just, Williams College

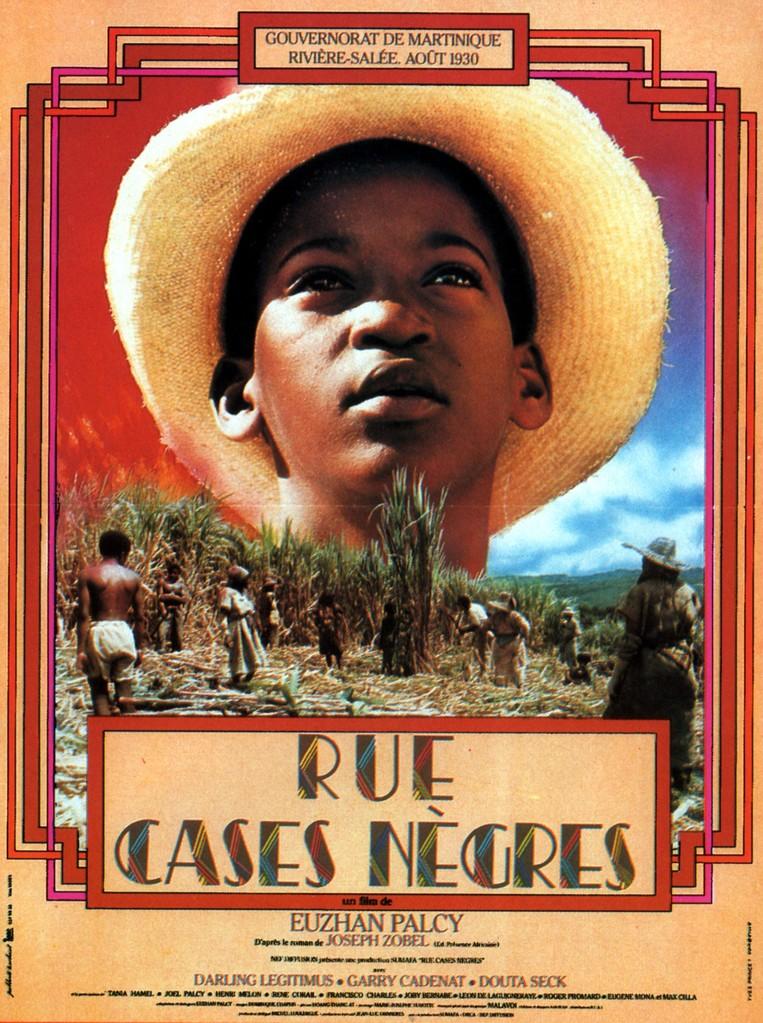

In a rich genealogy of French Caribbean intellectuals and artists, two Martinicans have recently received significant transatlantic accolades: artist and novelist Joseph Zobel (1915-2006), and film director Euzhan Palcy. Zobel’s 1950 generation-defining novel La Rue Cases-Nègres was re-edited by Penguin Classics in 2020, with a new foreword by Goncourt recipient Patrick Chamoiseau. For her part, in 2022, Palcy became the first Black woman to be awarded an Honorary Oscar from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as a recognition for her lifetime achievements. What connects these two towering figures of Antillean arts is precisely La Rue Cases-Nègres, which Palcy adapted into a full-length feature film in 1983. Zobel’s novel and Palcy’s film after it provide a sensitive yet unflinching portrayal of life in the vieilles colonies after slavery. Both works show what kinds of communities emerged in the wake of slavery and what kinds of legacies persisted. Each work came at a crucial time when the precious histories they attend to were at risk of being subsumed by larger political forces. Zobel published the novel four years after the Assimilation Act, better known today as the Departmentalization law of March 19, 1946. Palcy’s film came two years after the Decentralization project of 1981, which omitted to consider the particular living conditions of the départements d’outre-mer —an omission Aimé Césaire pointed out with one of his famous Assemblée speeches. But in addition to their sociohistorical interventions, these works also made original literary and cinematographic contributions to their respective craft. To discuss the geneses of both works and the artistic conversation in which Zobel and Palcy engaged across time and medium, we are joined by Dr. Sophie Saint-Just, who is assistant professor of French and Francophone Studies at Williams College. Saint-Just is currently writing a monograph on Palcy’s adaptation of La Rue Cases-Nègres, tentatively titled Revisiting Rue Cases-Nègres, a Martinican Landmark Film.

Let us begin with the novel. Can you tell us about Joseph Zobel and La Rue Cases-Nègres? What place does the novel occupy in his œuvre? What and whose stories does it tell?

La Rue Cases-Nègres was first published in 1950.1 While it was not Zobel’s first novel,2 it would remain the work most associated with his œuvre, partly because of the increased recognition brought by Euzhan Palcy’s film adaptation and partly because of its place as a bildungsroman by a Black Caribbean author. One of Joseph Zobel’s reasons for becoming a writer was his own thwarted career as a visual artist. Initially, his ambition was to be accepted at the Ecole des Beaux Arts to study architecture in Paris but the colonial administration in Martinique refused financial support for the formal artistic education of a dark-skinned Black man born and raised on a sugar plantation.3 Zobel channeled some of this disappointment into writing.4 He wrote La Rue Cases-Nègres in the late 1940s at a time when he felt an acute sense of displacement, having emigrated to France and working as a teaching assistant at a high school near Paris. In the novel, Zobel transforms his story into a bildungsroman that retraces the formative years of his protagonist, José Hassam. He fictionalizes some of the happiest times in his life, from his childhood near Petit-Bourg in Martinique, at the sugarcane alley, the area on the plantation where sugarcane workers and Afro-descendants of the formerly enslaved lived. In his bildungsroman, Zobel conveys the workers’ dignity despite exploitative working and living conditions by focusing on their lives, their culture, and their knowledge.

The novel recounts José’s rural childhood with M’man Tine, the grandmother who raises him in the social and cultural community where he acquires foundational rue Cases-Nègres knowledge that will allow him to become a prolific Caribbean writer. It also chronicles José’s experience in the bourg and in the capital, Fort-de-France, where he is partially reunited with his mother, Délia, who is working as a laundress and domestic worker for a béké.5 There, José attends the French colonial high school and begins the difficult path to secondary education, one rarely open to Black children. Thus, the novel also explores some of the challenges of being a transfuge de classe et de race.6

The novel tells many other stories beyond José’s. It encompasses the human geography of the sugarcane alley circum plantation but also of the bourg and the capital in ways that capture the personal stories of secondary characters positioned along the island’s racial, social, class, and economic hierarchies. The other stories within the novel capture many dimensions of Martinican life: the plantation as an enduring post-enslavement framework of the early twentieth century; the limited access to elementary French colonial education and quasi exclusion from secondary education for children of the Black working-poor majority; the expansion of the capital, Fort-de-France, the emergence of new working-class neighborhoods there, and the faster pace of urban life; and the central roles played by women, especially poor working Black women, in Martinican society. It also depicts Martinique as a French colony. So in short, in Zobel’s larger œuvre, La Rue Cases-Nègres functions as a bildungsroman that is part fictionalized autobiography and part twentieth century origin story.

In 1983, a young director, Euzhan Palcy who was 25 at the time, adapted Zobel’s novel into the film we know today. How did the project come about and why did Palcy decide to make a film about this particular novel?

The genesis for the film began in Martinique. After the book was published it was struck by an unofficial ban because there were békés in Martinique who did not like how they were portrayed in it.7 So it circulated clandestinely. Euzhan Palcy has explained that her mother gave her a copy when she was a teenager. She found Zobel’s portrayal of the men, women and children living in the sugarcane alley to be groundbreaking: the ways by which his prose elicits recognition, and how his vivid, poetic descriptions give texture to the characters and humanize them. Zobel’s depictions of different generations of people, their realities, daily lives, names and nicknames, and mannerisms, his use of Creolisms in French, and his ability to invoke, on the page, individual and collective expressions of Martinican identity from the perspective of an insider resonated deeply with Palcy during her own formative years. She saw how Zobel places the Afro-Caribbean culture of the rue Case-Nègres at the center of José’s narrative of social mobility.

The novel also functioned as a mirror, allowing Palcy to recognize herself as a storyteller because of personal parallels she found. Palcy’s childhood was steeped in Afro-Martinican oral history and traditions just like José’s. She had a grandmother with whom she was very close, whose name was Amantine, like M’man Tine in the novel, and who was a gifted storyteller. As a child, Palcy had gravitated toward her elders, and the stories and knowledge they imparted. At school, she was praised by teachers for her ability to tell stories. She also grew up in a family that valued artistic practices. Reading Zobel’s novel helped her find her calling, to explore, define and trust her voice as a young Black woman born and raised in Martinique. Palcy decided that she would become a director and that her first feature film would be an adaptation of Zobel’s novel. She recognized itas a novel about past and present, and as a foundational cinematic narrative that viewers in Martinique (and beyond) needed.

Before Palcy left for France, she began to chart her course and prepare herself for the métier of director. She watched mainstream American and French films shown at la salle paroissiale, on Sundays after church, developing a critical eye for racialized representations. With the tacit approval of her parents, she also snuck out to see works like François Truffaut’s L’Enfant sauvage, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Costa-Gavras’ Z and State of Siege,8 and Orfeu Negro with Marcel Camus,9 films that were redefining the canon and expanding the form. They helped Palcy reflect on how she would cast her own gaze as a cinéaste. These films gave her some of the Western cultural capital necessary to be accepted at a premier film school in France, Louis Lumière, but they also inspired her to form her own cinematic language. Because possibilities were few in Martinique, she created her own opportunities to practice her craft. In high school, she turned her role as a writer reading her own poetry on a local television show10[10] into a directing opportunity and shot her first featurette La messagère (1974).

Crucially, it is also in Martinique that Palcy created conditions to write different versions of her screenplay and continue to develop her vision. As she started re-imagining the novel as a film, gathered notes, and mapped her adaptation, she continued to observe, define, and expand her vision. When she left Martinique to go to film school, she literally carried her vision in her luggage, in the form of notebooks and versions of her screenplay, so she could hold on to that vision when confronted with the challenges of making Rue Cases-Nègres as a first feature: applying for funding, finding a French producer, a television channel to co-produce, a distributor, etc.

Rue Cases-Nègres was a rite of passage for my generation. I remember going to see it in middle school with my whole class at the movie theater in Pointe-à-Pitre for a special screening — we also did this for Siméon, Palcy’s 1992 film starring Jacob Desvarieux. What about you? Did you discover the novel before the film or the other way around? When did you first see Rue Cases-Nègres, and do you remember the first impression it made on you as a young Caribbean?

2023 marks an important anniversary for the film: it was released in 1983, four decades ago. What I distinctly remember is that, once I saw the film, it stayed with me and has remained with me ever since. It gave me a sense of belonging. Both my parents were from Martinique. I was born and raised in France but, thanks to the congés bonifiés,11 would go to Martinique every four years with my mother and my brother to visit my grandparents and other family members.

The film gave me a more complex understanding of my family across generations, the conditions in which they lived, how they survived, their inner tensions around gender, color, and class, but also their respective dreams. It facilitated intimate conversations on topics that antillais parents who emigrated to France for work did not necessarily broach. For instance, my mother Eugénie (1948-2021) confided to me that, like the character of Tortilla Saint-Louis in the film, she was taken out of school by her father, my grandfather, despite wanting to continue after passing the certificat d’études. The film also gave me an occasion to talk to my mother about the fraught remarks one of my French teachers made about Martinique, remarks that bore little resemblance with the Martinique I knew. In all, the film allowed me to really pay attention, to recognize valid modes of representations, and not to see Martinique through the distorted lens of 1980s French popular culture.

The film has been both a bridge and an anchor: a bridge that helped me construct my identity and an anchor to which I always return because its carefully built layers show us who we are, sa nou yé or ka nou yé, as antillais/guyanais. It is a film that teaches you to really look because, as you watch José’s journey unfold onscreen, you also see the legacy of enslavement, the mechanisms of Martinique as a tiered society, and the affirmation that Afro-Caribbean knowledge, culture, and identity can serve as a rampart against assimilation. This is why I decided to write a book about the film.

Adaptations from novel to film often feel like collaborations across time and space that produce new works of art. What did Palcy bring to Zobel’s novel to make the film hers? What creative liberties did she take?

The phrase “creative liberties” is really useful because it replaces the idea of faithfulness in adaptation with the notion of meaningful transformation. It reframes the discussion and helps move away from the urge to compare narrative forms as different as the text of the novel and the visual strategies of a film. Palcy explained it by saying that she “completed” and thus expanded on Zobel’s vision through film.12[12]

Palcy began to adapt the bildungsroman as she was herself coming of age as a young Black woman with intimate knowledge of rural and urban Martinique, and their in-between, le bourg. As I mentioned before, she began to map the film in Martinique. When she arrived in France and sought the rights to the novel, she shared her vision with Zobel while visiting him at his home in the South of France. As a teenager the novel had been “her bedside book.”13 Born and raised in Martinique, and steeped in the Afro-Caribbean oral tradition since childhood, Palcy was an attentive, knowledgeable reader of Zobel. The frameworks she developed in her adaptation bring into focus the larger narrative threads of the novel, because her background, experience, and research enabled her to understand which dimensions were foundational. What I argue in my book is that Palcy was able to reimagine Zobel’s novel as a plantation and a migration narrative while also pushing the limits of the bildungsroman, a literary genre that often retraced the formative years of a male protagonist.14

As Martinican historian Véronique Hélénon reminds us Zobel’s novel is a “vibrant homage to his grandmother and mother.”15 Palcy adapts the novel into a coming-of-age film that also highlights gender to make visible the pivotal roles played by women in Martinican society, especially working poor Black women like M’man Tine. Let’s take, as an example of creative liberty and meaningful transformation, Délia, José’s mother. In the novel, Délia is a domestic worker and a laundress for békés in Fort-de-France, who essentially takes over from M’man Tine when the latter falls ill and after José passes the certificat d’études and moves to Fort-de-France to attend high school. In the film, however, the considerable weight, we could even say the burden, of paving the way, of creating the conditions for José’s success at school rests solely on M’man Tine. In Palcy’s film, José’s mother has passed. M’man Tine is his only living parent, so she moves to Fort-de-France, settles in a new neighborhood, and takes washing on to pay his exorbitant tuition fees. Palcy’s creative liberty is meaningful in the context of French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique, the larger Caribbean and beyond. There is even a Creole term for this because so many Black women had no choice but to be fanm doubout.16 Amplifying the role of M’man Tine is not erasing Délia: in fact, viewers see a photograph of Délia a couple of times in the film. Rather the film emphasizes M’man Tine’s drive, sacrifices and resourcefulness, not simply as a personal trait but as part of what Martinican scholar of Caribbean and African ideas and philosophy Hanétha Vété-Congolo theorized as douboutism.17[17] Despite a life of underpaid, backbreaking work, grief, and scarcity, M’man Tine mobilizes resources that she does not even have to help José escape intergenerational poverty: a life of barely paid labor in the cane fields. Joseph Zobel writes in the novel that it takes the efforts of two generations of women to make a José Hassam. In Palcy’s cinematic re-interpretation, M’man Tine undertakes this lifting alone.

Another example related to women and gender is how Palcy widens the scope of the bildungsroman narrative, which has traditionally focused on male protagonists. She does so by developing the character of Tortilla Saint-Louis, a teenage girl who is one of José’s friends. With Tortilla’s beginning-to-end story arc, an arc that is not in the novel, Palcy contrasts José’s and Tortilla’s paths to social mobility, drawing attention to gender, access to education, class, and poverty in nuanced ways that linger.

There are many other meaningful ways by which Palcy, as a director, expands on the novel. Thinking about how and why she translates what she sees as crucial aspects of the novel to the screen, tells us about the film’s discursive strategies. You can see this in the difference between the titles of novel and film: the bildungsroman La Rue Cases-Nègres refers to the specific story of Joseph Zobel’s semi-fictionalized childhood, a personal space of memory and remembering, whereas Euzhan Palcy’s coming-of-age film Rue Cases-Nègres—note the omission of the definite article—reimagines a collective space of memorialization, tension, and belonging which contain larger discourses about Martinique, past and present.

What are some of the challenges Palcy faced in making the film, in terms of production or funding?

Euzhan Palcy has recalled the many challenges she faced in making the film. As a Black woman in her twenties, she was not taken seriously because of her youth, her skin color, and her gender. She was an outsider to the Parisian milieu of French cinema. She wanted to direct a fiction film about Martinique in the 1930s with a majority Black cast, for which she had written the screenplay, and which included dialogue in Creole. There was no one quite like her in French cinema in the 1980s. Certainly, there had been highly educated, sometimes formally trained Black women filmmakers, Francophone and Creolophone, who had made fiction films before: among them were Sarah Maldoror (1929-2020) née Ducados, born and raised in France, and Elsie Haas, from Haïti and a former student at Les Beaux-Arts, who made mostly documentaries and militant fiction films in the late 1960s and 1970s. There were also, of course, African women filmmakers, like Safi Faye (1943-2023), who attended Louis Lumière in 1972, just as Palcy would later do.

On the one hand, Palcy was supported but, on the other, she was second-guessed. The Centre National de la Cinématographie (CNC) granted her avance sur recettes funding, signaling that the screenplay she presented was one of the strongest among a very competitive pool. She needed a French television channel to co-produce the film: one agreed to but then used stalling tactics to try to renege on its promise. The co-producing French television channel asked Palcy to write another screenplay and direct a short film. Palcy returned to Martinique to make the moyen-métrage L’Atelier du diable (1981) to not lose the CNC state funding she had been awarded for Rue Cases-Nègres.18 And while that funding was significant, it was still less than a third of the film’s budget. To make the film she had imagined— remember it is set in 1930s in Martinique and so it is a “period film”—Palcy also acquired additional funding from Martinique and Guadeloupe. Finding aproducer also proved difficult:she eventually worked with two first-time producers and a third established producer, Claude Nedjar, who helped secure a wide French distribution deal.19 As well, weather during principal photography delayed completion of the film.

Palcy shouldered many tasks herself and met these challenges much as M’man Tine responded to those she faced. In a pivotal scene, Palcy quotes verbatim from Zobel when M’man Tine confronts yet another setback and exclaims “Mais ils ne savent pas quelle femme de combat je suis!” Because as a young director her vision was already undeniable, François Truffaut—who was introduced to Palcy at the insistence of his daughter, Laura—gave her feedback on her screenplay. He recognized it as “a beautiful piece” that was “so original”20: he “loved the script, the story, and the characters.”21 He understood what she was trying to achieve and helped Palcy assemble a crew of technicians for the film. Marie-Josèphe Yoyotte, a major film editor, whose father was from Martinique and whom Palcy met through Truffaut, also recognized Palcy’s vision and worked with her both on the featurette, L’Atelier du diable and on Rue Cases-Nègres. In Martinique and the French Caribbean, the distributor Alizé made concessions that helped the film.

The film and the novel are enjoying very rich transatlantic afterlives that seem mutually beneficial—either the novel brings the reader to the film, or the film brings the viewer to the novel. The novel’s English translation was recently re-edited, and there is also a bande dessinée adaptation that came out in 2018. What keeps us coming back to this story?

The novel was not widely available after its initial publication. That changed when the pan-African Francophone maison d’édition Présence Africaine acquired the rights and re-printed the novel in 1974. This revived interest in the novel, re-established its importance, and made it accessible to more readers, including readers from the Francophone African diaspora. Readership increased again when the novel was translated into English as Black Shack Alley by Keith Q. Warner, an Anglophone and Creolophone Trinidadian scholar who, as a person of African descent from the Caribbean, was familiar with many of its themes. The translation was published by Three Continent Press in 1980. The novel’s status as a bildungsroman of world literature was cemented by a 2020 Penguin Classics re-edition with Warner’s original introduction, translation and glossary, and a foreword by Patrick Chamoiseau.22

The film’s reach extends beyond insider audiences, even to those who may not pick up on the precise ways by which Palcy recreated 1930s Martinique or celebrated antillais performers as part of her cast. For instance, non-Caribbean viewers might remember M’man Tine as a tenacious grandmother even without understanding how Palcy positions her at the center of José’s story of social mobility. A non-Caribbean audience might even recognize that Palcy employed Darling Légitimus, a veteran actress, to depict M’man Tine but unlike an insider audience they won’t recognize M’man Tine as the figure of the fanm doubout. As a director, Palcy managed to make a film that resonates with many kinds of audiences even as it speaks in very specific ways to the collective imagination and lived experience of viewers from Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, and other parts of the larger Caribbean and African diaspora.

We keep returning to this story because both novel and film rely on conventional forms of storytelling to present insider narratives, which offer a complex picture of Martinique post-enslavement while also gesturing to the present. I know you are familiar with the work of Martinican philosopher René Ménil (1907-2004). His great nephew, Alain Ménil (1958-2012), also a philosopher wrote an insightful essay on the film, in which he reflects on Palcy’s ability to translate “les Antilles de l’intérieur,” that is from the inside.23 In my book, I argue that this insiderism is what makes the film a landmark, what keeps bringing insider and outsider audiences back, and what explains its commercial, popular, and critical success.

Returning to the cinematic space Palcy imagined, we can see in a new light the narrative techniques and film language of a major director at the very beginning of a career that would take her to the Sundance Institute Directors Lab, Hollywood, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris for a major retrospective in 2023. Regardless of which “us” we are, this is the film to see if we want to understand the legacies of enslavement, of the plantation system, and of colonialism in the Caribbean. We keep coming back to this story because the insider’s perspectives of novel and film posit that the Afro-Caribbean space of the rue Cases-Nègres is a foundational site of knowledge that actively undoes the colonial gaze and mediates by remediating.

- Joseph Zobel, La Rue Cases-Nègres (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1974 [1950] 2000).

- Euzhan Palcy, Rue Cases-Nègres, France. 101 min. Color. SUMAFA Productions (1983).

- Joseph Zobel, Black Shack Alley, trans. Keith Q. Warner, with foreword by Patrick Chamoiseau, trans. Charly Verstraet and Jeffrey Landon Allen (New York: Penguin Books, 2020).

- Joseph Zobel, Michel Bagoe, & Stéphanie Destin, La Rue Cases-Nègres (Paris : Présence Africaine, 2018).

Notes

- The first two editions of the novel were published by Parisian houses: Editions Jean Froissart in 1950 and in 1955, Editions des quatre jeudis. ↩︎

- The novel was preceded by Les jours immobiles: roman antillais (1946) and Diab’-la (1946) and a collection of short stories Laghia de la mort (1946). In his twenties, Zobel also published several short stories in Martinique in the newspaper Le Sportif. ↩︎

- Sylvie César, Rue Cases-Nègres : Du roman au film, étude comparative (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1994), 21. ↩︎

- Throughout his life, Zobel was also a painter, potter, sculptor, and photographer, as explained by his granddaughter, Charlotte Zobel in the INA video excerpt embedded in Bruno Sat’s following article about the discovery of a trove of Zobel’s photographs and a subsequent exhibition of his work. Bruno Sat, “La photographie, une passion cachée de l’écrivain martiniquais Joseph Zobel,” La 1re France TV Info, May 19, 2018, https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/photographie-passion-cachee-ecrivain-martiniquais-joseph-zobel-590699.html. ↩︎

- The term béké refers to the group of White Creoles, descendants of French settlers who arrived in the French Caribbean in the seventeenth century, established enslavement, and a plantation economy based on the commerce and production of sugar. ↩︎

- A person whose experience of social mobility is marked by their racial and class outsider status. ↩︎

- Euzhan Palcy, “L’Amour sans je t’aime” (Special features DVD), Rue Cases-Nègres. 1983. DVD, 2010. ↩︎

- Georges Alexander, “Euzhan Palcy,” Why We Make Movies: Black filmmakers talk about the magic of cinema (New York: Broadway Books, 2007), 214. ↩︎

- Michel Cyprien and Stephan Krezinski, “Euzhan Palcy : Rue Cases-Nègres,” Dossier CNC Collège au Cinéma 186 (Paris: Idoine Production, 2010), 2 , https://cdn.reseau-canope.fr/archivage/valid/N-9297-13844.pdf. ↩︎

- Ally Acker, Reel Women: Pioneers of the Cinema: 1896 to the Present (New York: Continuum, 1991), 119. ↩︎

- Congés bonifiés are travel subventions given to public servants who are from the DROM COMS but reside and are employed in continental France. ↩︎

- Euzhan Palcy also states this in “L’Amour sans je t’aime.” ↩︎

- Cyprien and Krezinski, 2. ↩︎

- For another important contemporary French Caribbean bildungsroman told from the perspective of a female protagonist, see Akosua Fadhili Afrika/Marie Léticée, Moun Lakou (Matouri: Ibis Rouge Edition, 2016), and excerpts translated by Kevin Meehan, Winner of the Anne Frydman translation Prize: Marie Léticée, “from Camille’s Lakou (Moun Lakou),” trans. Kevin Meehan, The Hopkins Review 16, no. 1 (2023): 70-82, https://doi.org/10.1353/thr.2023.0012. ↩︎

- Véronique Hélénon, “From the Sugar Plantation to the Colonial Administration,” in French Caribbeans in Africa: Diasporic Connections and Colonial Administration 1880-1939 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 17. ↩︎

- Literally a woman standing erect. ↩︎

- Hanétha Vété-Congolo, “Le douboutisme dans les sociétés caribéennes créolophones,” in Pluton Magazine Féminisme : (en) jeux d’une théorie, ed. Germain N’Guessan Kouadio (Abidjan : Les Éditions INIDAF, 2019): 132-170, https ://pluton-magazine.com/2019/09/23/le-douboutisme-dans-les-societes-caribeennes-creolophones/. ↩︎

- June Givanni, “Interview with Euzhan Palcy,” ed., Ex-iles: Essays on Caribbean cinema, ed. Mbye B Cham (Trenton, N.J.: African World Press, 1992), 292. ↩︎

- The two producers were Michel Loulergue and Jean-Luc Ormières. See Cyprien and Krezinski. 2; and Henri Micciollo, “Rue Cases-Nègres, Itinéraire d’un apprentissage,” Ecrans de cinéma, no. 298, (October 1983), 33. ↩︎

- Alexander, Why We Make Movies, 217. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Chamoiseau’s foreword was translated by Jeffrey Landon Allen and Charly Verstraet. ↩︎

- Alain Ménil, “Rue Cases-Nègres ou les Antilles de l’intérieur,” Présence Africaine, no. 129 (1984): 96-110, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24350963. ↩︎