Denise Davidson, Georgia State University

Announcing itself as “loosely inspired by the work of Honoré de Balzac,” (librement inspiré de l’œuvre d’Honoré de Balzac) Marc Dugain’s 2021 film, Eugénie Grandet, follows the basic plot of the source novel, which is set in Saumur during the Bourbon Restoration. Twenty-three-year-old Eugénie lives with her parents in an old, damp, poorly maintained house, waiting in vain for her miserly father to arrange for her to marry. Her Parisian cousin Charles arrives one evening only to learn that his father has gone bankrupt and committed suicide. During the few days he spends with the family, Eugénie falls in love with him, and they promise themselves to one another before Charles leaves to seek his fortune in the colonies. After her father’s death several years later, Eugénie discovers that she has inherited a huge fortune, but also that Charles has returned to France and is planning to marry someone else.

Although the film retains the outline of this story, Marc Dugain introduces significant changes to render more visible key themes of Balzac’s 1833 novel and make them accessible to contemporary viewers. Above all, the film explicitly explores limits on female agency in a patriarchal society and the role of money as a form of empowerment.

To critique the excessive power of men over women and of money over society, Balzac portrayed Eugénie and her mother as living under complete control of the miserly father / husband, Monsieur Grandet, whose decision not to dower his daughter keeps her from experiencing what Balzac believed all women find most satisfying: love, marriage, and children. The book is in many ways a tragedy, depicting the unfulfilled life of a provincial woman whose only experience of love is brief and disappointing. At the same time, the novel depicts Grandet’s obsession with gold as an exaggerated version of the general tendency in post-revolutionary society to prioritize money over all else. Eugénie’s cousin Charles also devotes his life to chasing money, fleeing France after his father’s bankruptcy to seek his fortune in the slave trade. When he returns and his future in-laws refuse to consent to the marriage he hopes to enter, Eugenie chooses to cover Charles’s outstanding debts with a portion of the fortune she inherited at her father’s death, reflecting the power she has gained from money as well. Balzac’s novel highlights the unfair and unhappy consequences of an intensely patriarchal society and the contradictions of the emerging capitalist system but offers no method for resisting those structures.

Marc Dugain’s film provides such a method. By tracing Eugénie’s evolution from a passive daughter shaped only by her experiences of home and church, to an independent woman who exercises her power over the men and women around her, the film highlights her growing resistance to patriarchal society and its money-grubbing tendencies. If Eugénie and her mother appear to accept their subordination to Grandet at the film’s beginning, by its end, Eugénie is not only in control of her own life but shaping the lives of others thanks to her large inheritance.

Eugénie Grandet is in many ways a beautiful film. The acting is excellent, and the setting produces an atmosphere that matches the house described in Balzac’s novel: rooms are dark, undecorated, and simply furnished, with only the dim light provided by a single window. Cracked, brown walls look like they haven’t been painted in decades. The film immediately draws viewers into this world, one in in which the women have so little stimulation that their emotional and intellectual lives have shut down. The contrast between the Grandet home in Saumur and those of their Parisian relatives, who enjoy spacious, beautifully decorated rooms, could not be greater. That contrast helps viewers understand how and why Charles would have assumed that his uncle was poor when he saw how the family lived.

The opening scenes of the film offer a powerful juxtaposition between the realms in which female and male characters act and the extent to which each can choose how to exercise agency. First, we see Eugénie at church struggling to find something to confess and asking whether it is a sin to wish for a great love. We then jump to her father, outdoors, negotiating the sale of stones from a church he purchased during the Revolution. The next scene portrays the Grandet women’s everyday existence and the unchanging rhythm of their lives. Seated near a window sewing in the dim light, Eugénie asks her mother when she will be able to marry. Her mother responds that her father will not let her end up a spinster. When the clock strikes five, mother and daughter silently put down their needlework, head to the table for their evening meal, and wait with blank facial expressions for Grandet to join them. He arrives breathless and satisfied, happy about his negotiations with the stone merchant. Charles’s unexpected arrival takes on even more significance because of what we have seen of the women’s otherwise routine existence. Eugénie feels pity and eventually love for to her cousin, which leads her to do all she can to help him, even betray her father’s trust by giving her cousin a sack of gold coins she had received as birthday gifts over the years.

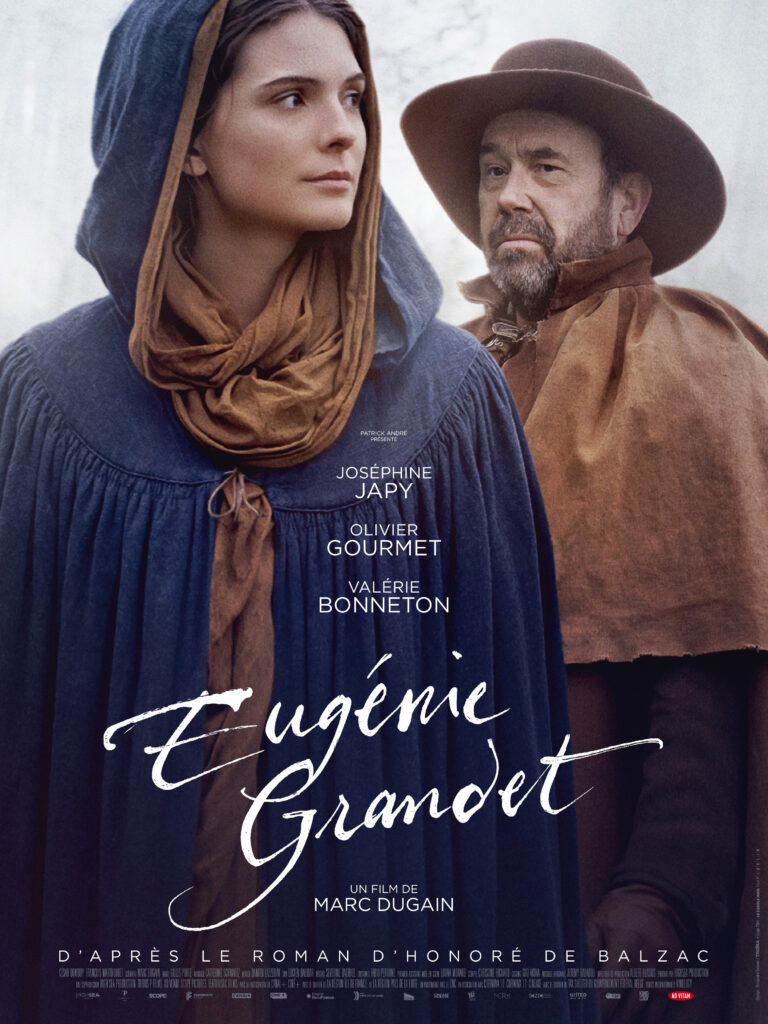

As the film progresses, the actress who plays Eugénie, Joséphine Japy, subtly reveals Eugénie’s transformation. We see the resentment in her eyes when her father criticizes her for taking long walks with her cousin rather than staying home to work. Eugénie’s evolution toward outright resistance becomes most visible in a scene at the dinner table with her father, five years after her mother’s death and not long before his own. When Grandet asks Eugénie what she did that day, she responds bitterly, “I led this life that you chose for me, a life where nothing happens.” (J’ai mené cette vie que vous avez choisi pour moi, une vie où il ne se passe rien.) (1:16:30) That is the beginning of a monologue in which she laments that women can do nothing except wait for “men to decide” (la volonté des hommes). Eugénie finally accuses Grandet of killing her mother, who saw death as relief from the life her husband had forced on her. When Grandet asks Eugénie why she no longer attends mass as she used to do so assiduously, she replies: “I understood that God is nothing but an invention of men to oppress us more.” (J’ai compris que Dieu n’est qu’une invention masculine pour nous soumettre encore.) (1:18) Although Balzac would never have written this kind of dialogue, the scene allows the character to articulate thoughts that a young woman like Eugénie arguably could have had and demonstrates her growing resistance to her father’s control over her life and to male domination in general.

Beyond its critique of the unfairness of patriarchal society, the film draws attention to the period’s obsession with money and the power it carried. We see this fixation in Grandet’s willingness to cheat and dissemble to turn a profit, including a plan to satisfy his brother’s creditors while making a profit himself and in scenes related to the sale of wine to Dutch merchants visiting Saumur. Grandet says nothing while at a raucous meeting in which local winemakers negotiate collectively with the merchants, but he manages to outbid his competitors by secretly negotiating on his own. The members of his community may resent Grandet’s methods, but they fear and respect his business acumen. His money allows him to dominate the local economy and the people around him, including his banker and lawyer, who obsequiously cater to his whims in the hope that Grandet will allow Eugénie, his sole heir, to marry into their families. Once Eugénie inherits her father’s wealth, she too dominates everyone around her, though she does it with kindness, as when she doubles the annuity her father had promised their loyal servant, Nanon, in his will. Before rejecting her provincial suitor’s proposal of marriage, Eugénie asks if he knew how wealthy she was all along, voicing her awareness of how much money played a role in his wooing of her. She then travels by herself to Paris to pay off Charles’ debts and refuses to rekindle their relationship once he learns that she was not in fact poor. Money allows her to choose how to live her life and to forsake marriage and the possibility of love in the name of freedom.

In highlighting Eugenie’s growing assertiveness in ways that Balzac’s novel did not, Marc Dugain manages to bring the themes of agency and resistance to the surface and so, perhaps, to cast the novel and its commentary on society in a new light.

In exposing these spaces for female agency and freedom within a patriarchal society, the film raises questions about agency in general and resistance to oppression. All of us live under constraints that limit our ability to act, limitations based on societal norms, economic realities, familial responsibilities, and so on. The extreme constraints placed on Eugénie by her miserly father may seem to efface her agency, to give her virtually no space to act on her wishes, or even to understand what her wishes may be. But once her father dies and she inherits his fortune, Eugénie can and does exercise agency. Money gives her the power to shape men’s lives. Even in the novel, with its less visible empowerment of the character, Eugénie manages to exercise agency. By informing Charles that he missed the opportunity to marry into one of France’s wealthiest families and marrying a man who will accept marriage on her terms (giving her hand, but not her heart or her body), Eugénie takes revenge on Charles while also shaping his destiny. She then chooses how to lead her life and how to spend her money.1 In highlighting Eugenie’s growing assertiveness in ways that Balzac’s novel did not, Marc Dugain manages to bring the themes of agency and resistance to the surface and so, perhaps, to cast the novel and its commentary on society in a new light.

As scholars of the period know, the Napoleonic Code drastically limited women’s freedom to act. Married women lived under legal guardianship of their husbands, single women under that of their fathers or another adult male relative. However, women were not wholly without power, another point that the film underlines. In a scene that might surprise those unfamiliar with French inheritance law, Grandet’s lawyer reminds him that, should his wife die, his daughter will inherit the property that Madame Grandet brought to the marriage, including their home. When Grandet expresses rage at the possibility of losing control over any of “his” property, the notary suggests that Eugénie be encouraged to renounce her inheritance rights. Despite Grandet’s belated effort to save his wife by forgiving his daughter for giving away her gold, Eugénie’s mother dies, and in the next scene, we see the daughter signing the paperwork as her father looks on with a satisfied expression. Although he has managed to maintain control over his wife’s property, the scene reminds viewers that even in this highly patriarchal society, married women’s property remained theirs, even if their husbands managed it. This was not the case in the Anglo-American world.

Because of its thoughtful rendering of early nineteenth-century provincial France, including property management, family dynamics, and women’s place in society, I could imagine assigning this film in a class focused on modern French or European history. It engages with many of the issues typically covered by such courses, including the French Revolution’s impact on ideas about property and wealth, and the rise of modern capitalism. The film could also lead to interesting discussions about gender and class in early nineteenth-century France, as well as the feminization of religion. However, I do not think I would assign the film without also assigning the book, in part because many of Eugénie’s actions (walking unchaperoned in the countryside with her cousin and later traveling to Paris by herself, for example) move too far beyond the period’s norms for women of her class. Requiring students to read the novel and watch the film could inspire stimulating discussions about how rewriting Eugenie’s story permits reconsideration of questions related to women’s autonomy in nineteenth-century France and beyond. Such conversations could offer an opportunity to reflect on how social norms, economic systems, and family responsibilities limit our range of actions, and how one might exercise agency within given structures or even resist them outright.

- Marc Dugain, Eugénie Grandet (2021) France. 104 mins. Ad vitam, Highsea, Tribut P., & Scope Pictures.

- Honoré de Balzac, Eugénie Grandet (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Bibliography

Richard M. Berrong, “Art, Transformation, Liberation: Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet,” Romance Quarterly 60 (2013): 175-183.

Notes

- In his analysis of the novel, literary scholar Richard Berrong emphasizes Eugénie’s agency vis-à-vis the question of marriage: “She has her suitor, the Président de Bonfons, make clear to Charles that, in abandoning her for the titled but ugly and not rich Mlle d’Aubrion, he has just thrown away a chance to marry one of the colossal fortunes of France. Then, having crushed Charles where she knows it will hurt him the most, the calm and collected Eugénie proceeds to set up a life without her cousin … in which she exercises complete freedom of action.” Berrong, “Art, Transformation, Liberation: Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet,” Romance Quarterly 60 (2013), 179. ↩︎