Aubrey Gabel, Columbia University

Since June 24, 2022, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization [1], any artistic representation of abortion has felt all too timely–or all too belated. Audrey Diwan’s 2021 film adaptation of Annie Ernaux’s biographical novel L’événement (Gallimard, 2000), which describes her clandestine abortion in Paris in the early 1960s, hit NYC cinemas in mid-May 2022, a mere month before the Dobbs decision. [2] (On March 3, 2023, the Villa Albertine in New York even staged a live reading of the novel, by physicians, activists, student organizers, writers, and others. [3]) Similarly, a suite of French comics about abortion–commonly referred to by its medical euphemism IVG (Interruption volontaire de grossesse)–have recently appeared. In Il fallait que je vous le dise (2019), the French-Canadian artist Aude Mermilliod recounts her abortion and her encounter with Martin Winckler (nom de plume of Marc Zaffran), a gynecologist who worked in a women’s health clinic before leaving medicine to write semi-autobiographical novels and medical thrillers. Two other recent comics center on the landmark 1975 loi Veil, which legalized abortion in France, and the Mouvement pour la libération de l’avortement et la contraception (MLAC), a feminist activist group that provided clandestine abortions in France and organized trips to countries where abortion was legal: Des salopes et des anges (2021), written by Tonino Benacquista and drawn by Florence Cestac, the first woman to receive the grand prix at the Festival d’Angoulême in 2000, and Le choix (2020), by the writer-illustrator couple Désirée and Alain Frappier.

Like most Francophone reproductive health comics, these three volumes have yet to be translated into English. And yet, their timeliness is not lost on American readers. Nor has it been lost on French readers, who must contend with a growing far-right and Catholic populism that has provoked large-scale anti-gay marriage protests and mediatized paranoia about wokisme and la théorie du genre. Not to mention endless handwringing about Procréation médicalement assistée or PMA (medically assisted procreation), which includes surrogacy (maternité de substitution, currently illegal for all couples) and in vitro fertilization (fécondation in vitro or FIV, legal for single or coupled cis women since 2021) [4]. Nonetheless, the French National Assembly did vote, on November 24, 2022, to enshrine abortion rights in the Constitution–an action that seems far less probable in the United States. [5]

Representing abortion in comics is not, of course, unique to French and French-Canadian publications. In the wake of Dobbs, The Washington Post published a piece by Michael Cavna about political cartoons criticizing the decision, as well as a report by journalist Hannah Good based on interviews with four American women about their abortion experiences, which were translated into comic art by Ana Galvañ. [6] A few years back, Hazel Newlevant, Whit Taylor, and OK Fox developed the Ignatz-award-winning anthology Comics for Choice: Illustrated Abortion Stories, History, and Politics (2017). [7] And a few years before that, Leah Hayes’ no-nonsense how-to guide, Not Funny Ha-Ha: A Handbook for Something Hard (2015), used a hand-scrawled second-person address and red-faced line drawings to walk readers through abortion basics.

Abortion comics like these speak to the relatively recent proliferation of Anglo- and Francophone comics about parenthood, pregnancy, sexism, gynecology, and other issues related to the experiences of women and those with uteruses. These reproductive health comics constitute a corpus of pedagogical or didactic works that represent aspects of reproductive health and sexuality long deemed taboo (like miscarriages and infertility, menopause, or orgasms) or underrepresented (like breast cancer, toxic shock, or endometriosis), related mental health issues (like postpartum depression), and even common medical procedures that remain unnecessarily shrouded in mystery (like how to insert an intrauterine device or IUD). [8]

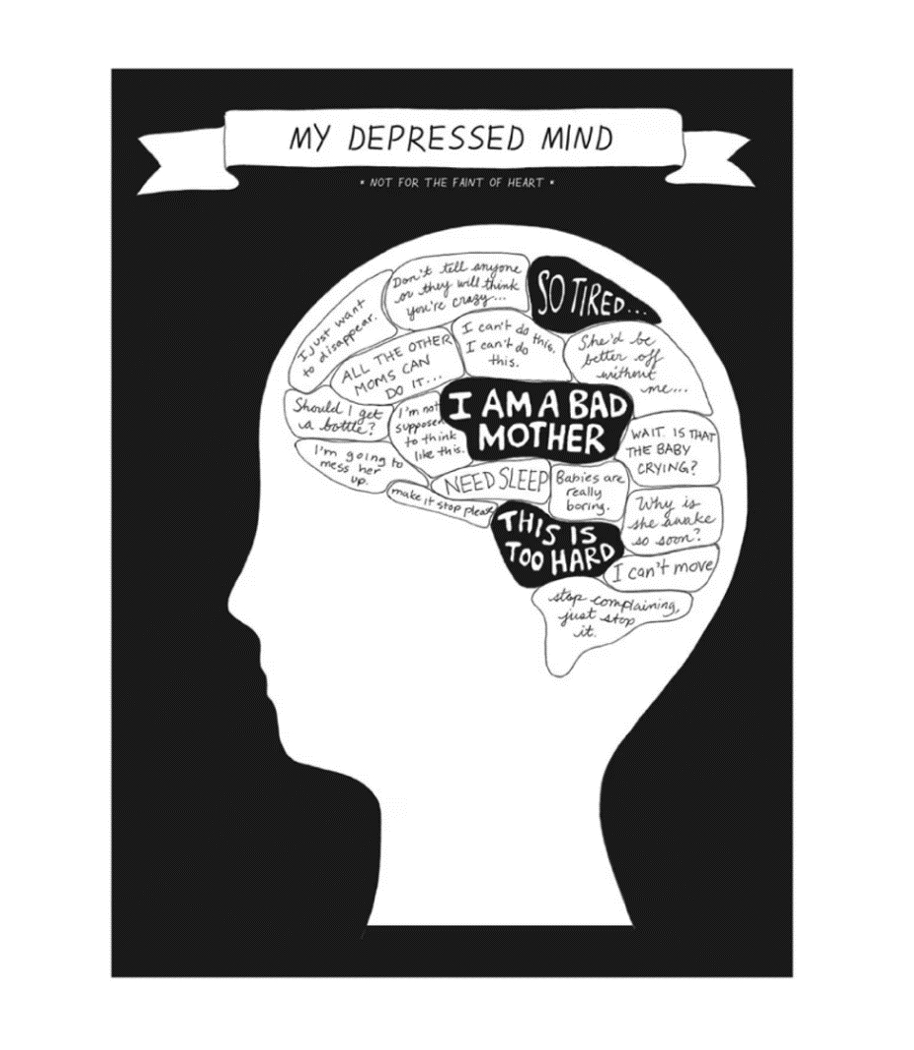

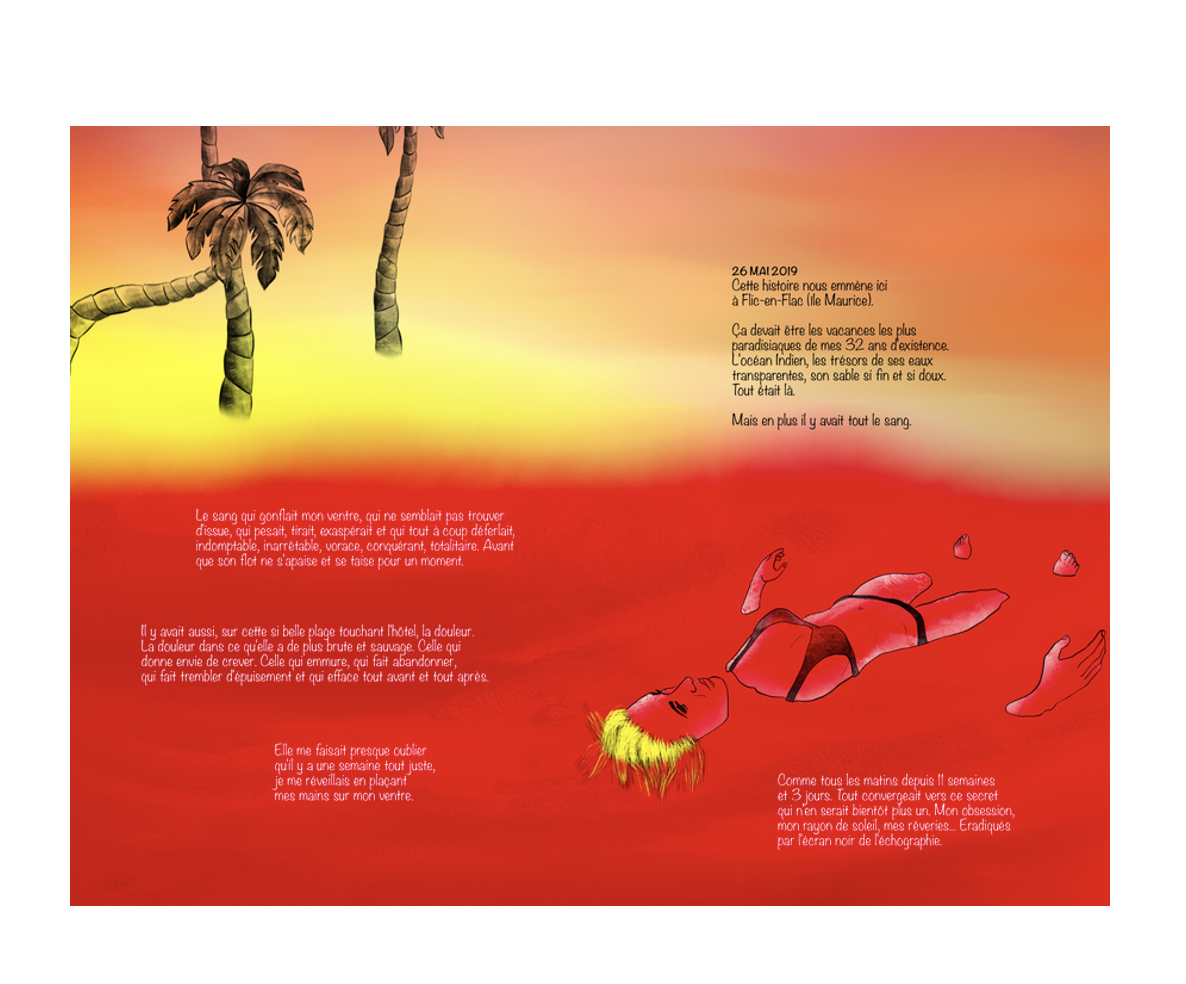

Generically, this corpus varies widely: from non-fiction gag strips written by healthcare professionals to autobiographical or semi-fictional narratives, webcomics, or single-panel frames, written and drawn by the artists themselves. Canadian artist Teresa Wong’s memoir Dear Scarlet (2019), for example, dissects how she, as a woman of Chinese descent, coped with postpartum depression; one minimalist black-and-white panel designs a new brain anatomy based on her shifting emotions (Image 1). Kalina Anguelova illustrates Swiss journalist Cléa Favre’s Ce sera pour la prochaine fois (2022), in panel-less freeform with a haunting color palette, using evocative images, like a woman bathing in a crimson-orange sea of blood, to retell the physically and emotionally excruciating experience of repeated miscarriages (fausses couches) (Image 2). Some comics lean into quirky relatability and border on cutesy, like American artist Lucy Knisley’s Kid Gloves (2019) or Mères Anonymes (2013), by the French duo Gwendoline Raisson and Magali Le Huche. These light-hearted examples often rely on the well-worn stereotype of the frantic, heterosexual mother, who coddles her children too intensely and makes do with fumbling male partners and outdated parenting books, whether it is Dr. Spock or Françoise Dolto. They nevertheless relay the all-too-relatable experiences of childbirth, nursing, and infant-rearing, or psychological concerns, like burn-out. In her account of her struggle with infertility, Un bébé si je peux (2021), Marie Dubois even repurposes whimsy to satirical advantage by depicting her anthropomorphized “lazy” ovaries lying about smoking and watching tv, while she visualizes the PMA process as an absurdist Mario game (Image 3).

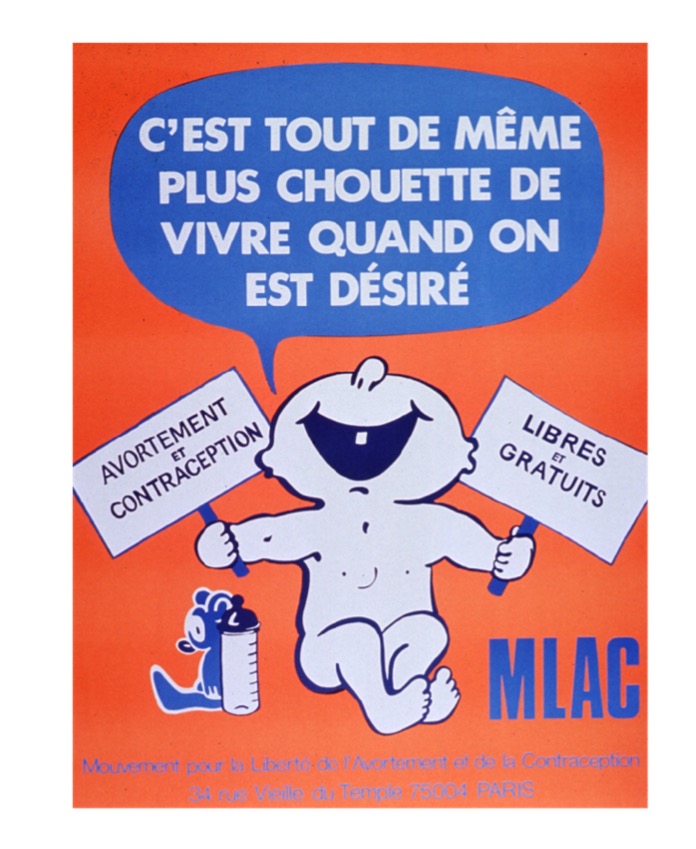

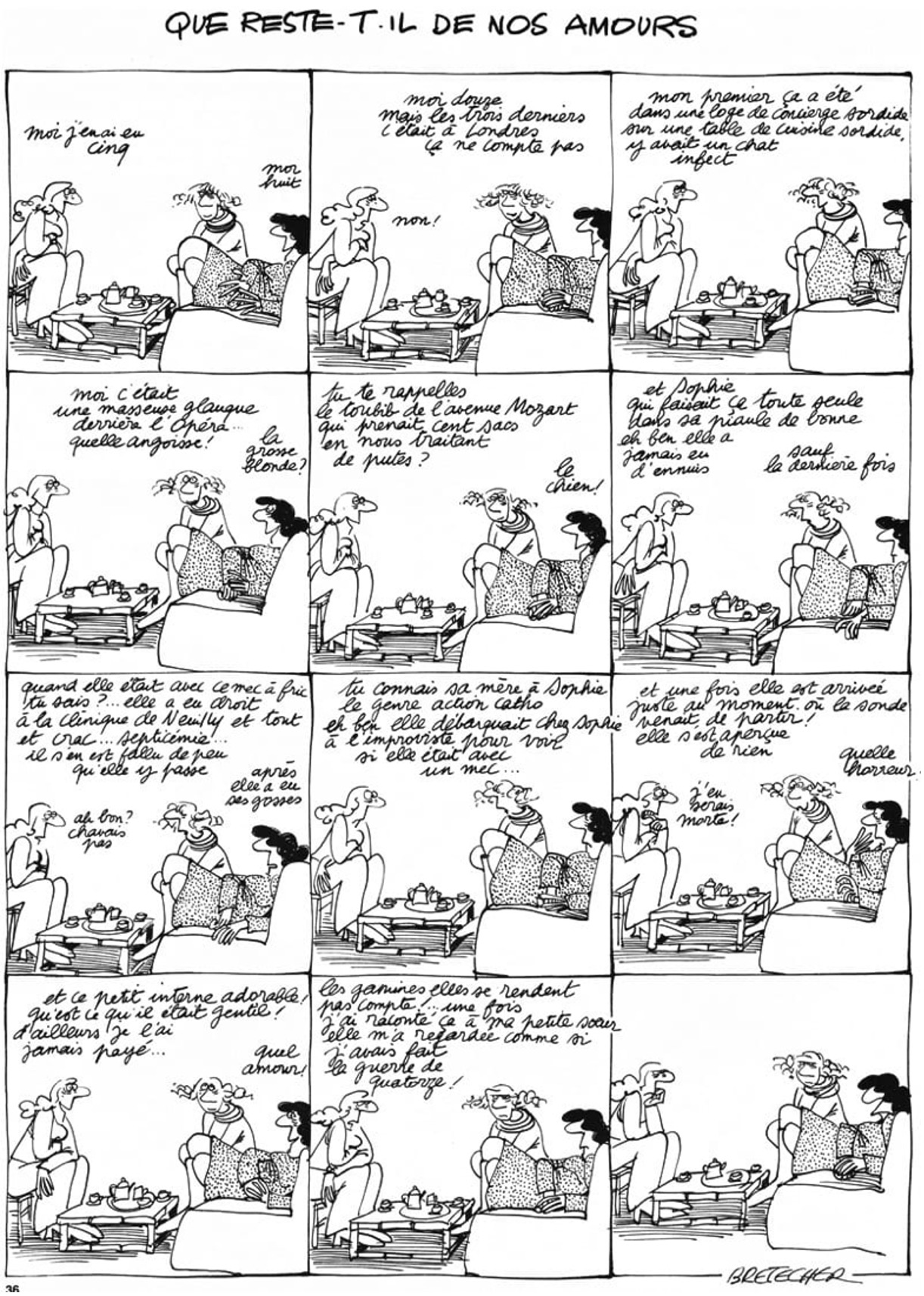

As cultural productions, comics and graphic art have been instrumental in shaping historical opinions about abortion. Contemporary reproductive health comics look back to a tradition of graphic feminist activism that dates to at least the 1970s. Feminist “comix,” or underground comics and ’zines produced outside of syndicates, countered the male gaze of traditional comics, and of the adult comix scene, both of which targeted a predominately male audience and trafficked in sexist and misogynist tropes. Consider the French cartoonist Claire Bretécher, who drew posters for MLAC (Image 4) and produced a long-running strip, Les Frustrés, for Le Nouvel Observateur (1973-1981). Her biting political humor defended and reasserted newly acquired women’s rights. Her panel “Que reste-t-il de nos amours?” is exemplary: a woman seemingly describing past lovers is actually listing her own clandestine abortions (Image 5).

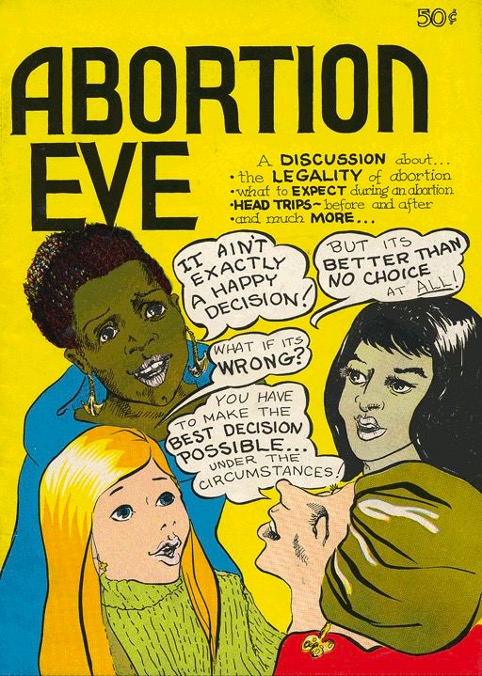

In 1974, U.S. illustrators Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli, the editors of Tits n’ Clits Comix (1972-1987), donned pseudonyms to publish Abortion Eve, which follows five women seeking legal abortions, just after Roe v. Wade (Image 6). [9] They imagine a multiracial community of women who empower each other to make decisions about their own bodies, outside of the purview of medical professionals and men. Women-led comics anthologies, like Wimmen’s Comix (1972-1992) and its offshoot Twisted Sister (1976, 1991, 1994-5), consciously politicized the social by representing women’s everyday fertility concerns, like miscarriages. [10]

If these feminist anthologies and underground comix were published in the U.S., they nevertheless invited international collaboration across nations and languages. French-Canadian author Julie Doucet, the 2022 Angoulême grand-prize winner, published unfiltered, grotesque drawings of hot-button topics (like masturbation or intimate partner abuse) in both France and North America. New-York-based French artist Françoise Mouly, who edited Raw (1980-1991), helped establish and maintain international publishing networks. Iconic American artist Aline Kominsky-Crumb later moved to France, where her daughter, Sophie, now works as a comics artist.

These artists are emblematic of what comics theorist Eszter Szép, drawing on Judith Butler and others, calls a hand-drawn practice of “vulnerable embodiment.” “Vulnerable bodies” evoke a laying bare of the body, or a willing, rather than defensive, exposure of the bodily self–one that calls for an affective response. [11] Drawing on this feminist graphic tradition, reproductive health comics can be pedagogically oriented, but they self-consciously represent such vulnerable bodies, like Favre’s, which demand to be validated, acknowledged, and invested with emotional or political potential.

Reproductive health comics also follow the broader post-#metoo cultural shift–transported into France as #balancetonporc–which has shed light on sexism in film, entertainment, and other industries, including comics itself. At the 2016 Festival d’Angoulême, the continued lack of social recognition for women comic artists came to a head when not a single dessinatrice was nominated for the grand prize. Le Collectif des créatrices de bande dessinée contre le sexisme called for a boycott of the festival, prompting international superstars Joann Sfar, Riad Sattouf, and Daniel Clowes to withdraw their names from the grand prize nomination in solidarity. [12]

In the post-#metoo era, comics about motherhood appear on the spectrum of affirmative feminist propaganda: these texts instruct their readers in basic concepts of twenty-first-century feminism or validate, through a rhetoric of identity politics, the experiences of (mainly heterosexual) mothers. French artist Emma’s webcomics series, published as Un autre regard (2017, excerpts of which were translated as The Mental Load, 2018) illustrates case studies of sexism: birthing procedures that are sometimes unwanted (epidurals) or largely unnecessary (episiotomies) as well as mundane experiences of catcalling and sexual harassment. [13] Emma juxtaposes third-wave feminist talking points–like “mental load” (“la charge émotionelle/mentale”) or the psychological weight of organizing household labor (Image 7)–and broader concerns in Leftist politics–like police violence against Muslims after the 2015 terrorist attacks in France and the murder of Adama Traoré. [14] In this way, she echoes millennial influencer feminists like the Instagram duo #CamilleetJustine (Camille Giry and Justine Lossa), who import American identity politics to challenge a reputedly race- and gender-blind French universalism.

Many didactic comics fit within the growing genre of graphic medicine, a subfield of the medical humanities that studies the implications of integrating comics into healthcare practices. As an interdisciplinary academic field, graphic medicine considers the relationship between graphic art and healthcare discourse, relying on the medium’s generic diversity (including graphic reportage, drawn memoirs about illness, etc.). [15] Like narrative medicine, it has pedagogical and therapeutic aims, but with a more activist bent; the Graphic Medicine Manifesto claims to challenge “dominant methods of scholarship in healthcare.” [16] Didactic comics can instruct healthcare workers in patient-centered care (read: bedside manner and humane treatment) or the diversity of patients and their experiences. Jenell Johnson, the editor of the anthology Graphic Reproduction (2012), emphasizes that graphic medicine offers a “critical incorporation of the caregiver’s or patient’s experiences.” [17] For instance, Johnson describes “never feeling more like a body” than when she underwent fertility treatment, which was ultimately unsuccessful; she claims comics freed her from pre-established “cultural scripts.” [18] Most investigations of graphic reproduction are long-form graphic narratives, but not exclusively (consider British artist Paula Knight’s one-off panels or Natalie Pendergast’s webcomics). [19]

In this context, abortion comics not only help people to anticipate their experiences and feelings during and after the procedure, but double as critical educational material for doctors. For example, Aude Mermilliod’s Le Choeur des femmes (2021) is a graphic adaptation of doctor-author Martin Winckler’s novel by the same name, which centers on Jean Atwood, a gynecological surgery intern who is seduced by the anti-conformist methods of Dr. Franz Karma. (His name evokes Harvey Karman, the doctor who popularized vacuum-aspiration abortion in the U.S., a technique that was later adopted by French militants.) The album offers a straightforward narrativization of Jean’s coming-to-terms with Franz’s unconventional practice. It includes several case studies (a 48-year-old woman who wants to get pregnant or a woman who has twice become pregnant with an IUD) and practical scenes that could readily serve in gynecological training (inserting an IUD or performing a vacuum-aspiration abortion). The novel and its graphic adaptation thus stage teachable scenarios in which Jean (a surrogate for the gynecologist-reader) is encouraged to be more compassionate and less judgmental with her patients.

The reader eventually learns that Jean herself is a complex human being, who is not only bicultural but intersex. This intersexuality does not lead Jean to question her identification as a woman but poses challenges in her sexual and romantic life; her partners are too often ignorant of or stupefied by her anatomy. In a soap-opera-like twist, the graphic adaptation reveals that as a urological intern, Franz assisted the suicide of an intersex individual named Patiente A (Camille), who became distraught after her genital operations were mangled by an overzealous supervising surgeon. Franz, it turns out, was also instrumental in convincing Jean’s father not to operate on her, a decision that provoked Jean’s mother’s suicide and profoundly shaped Jean’s own life and body. This whirlwind story–as absurd as its intrigue may be–is a profound meditation on the diverse physical and psychological effects of pediatric intersex surgeries on individuals. Intersex individuals remain underrepresented or pathologized in medicine, mainstream media, and literary analysis alike. Le Choeur des femmes recalls the memoir of Herculine Barbin–a 19th-century intersex individual who was assigned female at birth, forced to reassign male later in life, and who eventually committed suicide–as well as recent attention brought to historical gender non-conforming individuals by Anne Linton and Rachel Mesch. [20] The graphic adaptation’s persistent message is that French- and French-Canadian doctors are too paternalistic, conservative, and dogmatic, depriving people of control over their own bodies.

Reproductive health comics evoke the (politically) vulnerable body and, when read side-by-side, expose subtle cultural differences between the U.S. and France. Some reproductive health concerns–like unexpected pregnancies, difficulty learning to nurse, or postpartum depression– transcend cultural barriers, while others lay bare specific taboos or norms. French authors, for instance, joke about abortion or drinking during pregnancy, topics that are still largely out of bounds in many American contexts. Being an unemployed single mother in a French state with readily accessible social security becomes more of a psychological matter–a problem of isolation or excess time–than an imminent existential crisis. Mermilliod’s Le Choeur des femmes, like Emma’s Un autre regard, highlights conventions in the French medical field–like being entirely naked for annual physical examinations or giving birth while lying on one’s back–that are not practiced elsewhere. As Dr. Karma notes, speaking English means having access to research on medical interventions not commonly available in France, like pain treatment, cancer prevention, reparative surgery for sexual organs, surrogacy, and gender transition therapy (“démarches de transition”). [21]

Similarly, the gender essentialism of Raisson and Le Huche might rub many American millennials the wrong way, as their “anonymous mothers” find themselves in crisis after giving birth to boys, guffaw at the idea that men might help at home, and incessantly compare themselves to a beautiful Italian actress, and mother of eight, “Monica” (an avatar of Monica Bellucci, mother of two?). [22] If Francophone comics have a narrower understanding of gender identities and parenting roles, comics that are explicitly about motherhood, in both English and French, generally fail to represent complex parent-child relationships, notions of inheritance and belonging and burgeoning gender identity, the very questions that make Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006) and Who is my Mother? (2013) particularly compelling. [23]

The glaring heterosexuality and gender essentialism of many reproductive health comics writ large makes AK Summers’s Pregnant Butch: Nine Months Spent in Drag (2013), even more urgent. A few years before Maia Kobabe’s ground-breaking memoir Gender Queer (2019) would be banned from school libraries across the U.S., Summers’ powerful novel relayed the painful experience of gender dysphoria during pregnancy. The narrator, Teek, is a self-identified butch lesbian whose ideal gender representation is a boyish Tintin, complete with the iconic hair flick, and who conceals the physical condition of pregnancy by adopting a “fat mechanic” disguise. Despite their best efforts, Teek struggles with the emotional and physical changes induced by pregnancy. [24] Summers borrows iconic or conventional graphic imagery–from ukiyo-e prints to superhero comics–to push back against aggressively femme representations of the lesbian mother and to masculinize childbirth. For example, during labor, the narrator appears beneath a giant, onomatopoeic “No!,” humorously leaning away from a Hokusai-like swell, a visual metaphor for contraction cycles. [25] After the birth, a full-page panel depicts them as a topless boxer with a black eye, leaning back in the corner of a ring, casually cradling a breastfeeding infant with a gloved hand. [26] Summers’s clever play with gendering norms, both in and outside of comics, creates a distinctly butch depiction of pregnancy.

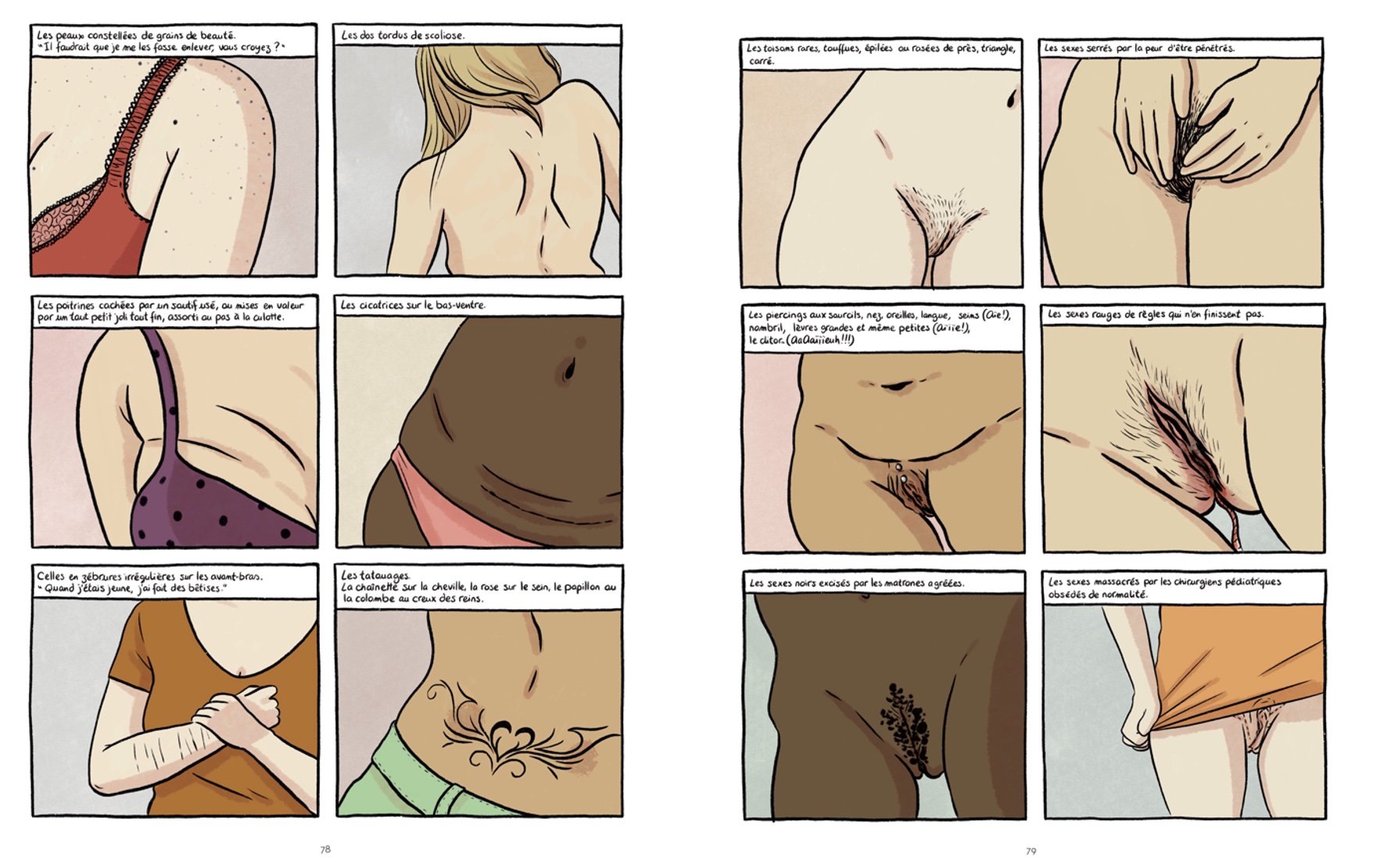

French reproductive health comics also demonstrate the relative dearth of BIPOC voices in graphic medicine–despite the disproportionate impact of negative healthcare experiences on them–and the increased influence of intersectional feminism. [27] If intersectionality is signaled by the occasional presence of a veiled or a Black or Brown woman, controversial practices, like female circumcision are often presented casually and through an overtly Western gaze, without any additional framing. On a masterful double page in which Mermilliod recreates (and desexualizes) Gustave Courbet’s painting L’origine du monde (1866), via a diversity of vaginal and vulva types, she nevertheless describes: “sexes noirs excisés par les matrones agréées” (black sexual organs excised by approving matrons) (Image 8). [28] While Black women are certainly not absent elsewhere in the volume (as in the frame of “lower abdomen scars” on the facing page), the condemnation of female circumcision is immediate, presumed to be enacted by women, and comes without any discussion of the cultural contexts in which it is practiced.

Comparisons between French comics and their Anglophone translations can also be revelatory. Inspired by a crisis of womanhood she experienced after breast cancer, Sohn’s Vagin Tonic (2018) is a detailed “user’s manual,” which tackles almost every imaginable issue related to vaginas and uteruses, including female ejaculation and cosmetic surgery. Sohn interviews friends and family members who represent diverse conceptions of heterosexual womanhood: child-bearers and mothers, women with only one breast, childless women, and so on. Liz Frances, the editor of the English translation, published as Vagina Love (2022), takes this gesture a step further, correcting the book’s implicit heterocentrism with Sohn’s blessing. Sohn drew new pages based on testimony from Bishakh Kumar Som, an Indian-American trans woman artist, and Shelby Criswell, a non-binary artist, and references other trans women, non-binary folks, and a bearded woman. [29] Som, who authored a graphic memoir about transitioning, Spellbound (2020), describes womanhood as a psychic and mental state; she refutes the assumption that one needs surgical or hormonal interventions to transition socially (Image 10). Chloe, a cisgender artist with short hair who often gets mistaken for a man, embeds the whole social construction of womanhood in the statement: “I proclaim myself to be a woman, I discovered myself as a woman, and society has chosen to recognize me as a woman.” [30] Criswell, the author of Queer as all Get Out (2021), affirms that being gender non-conforming or non-binary is an act of self-definition: “YOU decide that for yourself, and not anyone else” (Image 11). [31] As with Sohn’s missing breast post-cancer, the lesson is that being a woman is not an anatomical or hormonal state, nor a societal position. Sohn empowers the individual to model a gender expression that feels best for her. This identitarian position is didactic and pedagogical, but also activist, given widespread anti-trans rhetoric and legislation in the U.S. and France.

It is against this backdrop that I want to consider abortion comics. Anglophone and Francophone abortion comics, like other reproductive health comics with roots in graphic medicine, typically educate readers in abortion methods, and especially in the U.S., how to access abortion. They personalize and diversify abortion experiences, pushing back against dominant medical and political discourses. But they also shed light on what reproductive health comics avoid. Most importantly, why do many (but not all) pedagogical comics about fertility, anatomy, and sexuality remain largely silent about abortion? (Vagin Tonic and Mères anonymes mention abortion but do not discuss it, forgoing a prolonged description of abortion methods or experiences. [32]) This relative silence is most visible in American examples, which frequently elide the abortion debate entirely. Even those refuting essentialist representations of motherhood conspicuously separate abortion from reproductive health. When abortion access is in crisis throughout the U.S., this oversight–or apoliticism?–is dangerous for ongoing legal debates and the people impacted by them.

Given the criminalization of surgical abortions or efforts to limit the distribution of abortion medications in many parts of the U.S., it is no surprise that American comics adopt, by default, a militant stance. They normalize the experience of abortion, pointing to the sheer number and diversity of individuals who have had or seek them, and they provide additional resources to readers, like information about pro-choice organizations. While the need may be less pressing, French abortion comics are not devoid of this political impulse; in Le choix, Desirée Frappier frequently condemns historical (and modern-day) Catholic anti-abortion activism. More broadly, both French- and English-language abortion comics humanize the experience of abortion, not just by detailing the variety of circumstances that lead someone to want an abortion, but by pointedly including women who, like Ernaux in the 1960s, simply do not want to be pregnant or have children–no justification needed. All abortion comics discuss medical procedures from the individual or patient’s perspective. Even in the best of circumstances, abortions are uncomfortable and painful or happen under the wary eye of (often moralizing) healthcare professionals. Most importantly, these comics, like Abortion Eve, all involve processing feelings surrounding abortion, whether it be societally induced guilt or shame, fear, anxiety, ambivalence, or even relief.

As in reproductive health comics, reading French and English abortion comics side-by-side highlights cultural differences. Some are differences of medical practice. Francophone comics overwhelmingly represent vacuum aspiration abortions, while Anglophone comics, like Hayes’s how-to book, describe a broader array of abortion methods, including medications like mifepristone and misoprostol, a combination sometimes called Plan C, which can also be used to induce miscarriages (as is the case in Favre). Plan C’s double purpose is even more relevant given ongoing efforts to ban or criminalize the use and distribution of these medications: to criminalize medication abortion is effectively to criminalize a safe miscarriage. The Comics for Choice anthology, which includes short comics drawn by American cartoonists from across the U.S., also highlights historical abortion methods that proved less popular over time, like the so-called “D&C” (dilation and curettage) method, practiced by the militant underground Jane collective (1969-1973) in Chicago, among others. [33] D&C is still widespread in the American imaginary, especially among older women, but no longer widely practiced. In both languages, however, the tendency towards euphemism–whether it be using the terms IVG and D&C or a reluctance to detail medical procedures–poses striking pedagogical problems. Does medical terminology depersonalize and depoliticize the experience of abortion? Is it better to provide a detailed overview that warns patients of potential stumbling blocks–like excessive bleeding or armed guards outside of a clinic–or does that scare them out of using resources they desperately need?

This demonstrates the political import of an anthology like Comics for Choice, published in 2017 to defend a “fundamental reproductive right that continues to be stigmatized and jeopardized.” [34] In partnership with the activist organization We Testify, which highlights the abortion stories of BIPOC individuals and those in abortion deserts, the volume self-consciously represented people who had had abortions across the gender spectrum (including lesbians, transgender men, and non-binary folks) and from states across the U.S. (ranging from the very restrictive Texas to very liberal cities like NYC or Washington DC). [35] This ethnic, cultural, and regional diversity underscored the challenges of abortion access in 2017, like states in which cost was long prohibitive (thus requiring non-profit abortion funds). But this situation has only worsened, as abortions have since been banned or narrowly limited in more than a dozen states. Highlighting the hurdles that abortion seekers encountered in Texas or Tennessee even when the procedure was legal, these comics educated readers about national and international abortion law. Consider the Hyde Amendment, a rider to federal appropriations bills since the 1970s that bans the use of federal funds for abortion, or the Mexico City Policy (the Global Gag rule), which prohibits international NGOs that perform or promote abortions from receiving U.S. dollars. [36] If strips in the anthology denounced regional abortion laws or targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP laws), they also showcased local activism which, despite the efforts of heroic women, failed: like Wendy Davis and her 2013 filibuster against an anti-abortion law in Texas or Senator Dr. Dorothy Brown’s attempt to protect abortion in cases of rape and incest in Tennessee in 1967. [37] Across the black-and-white volume, real-life stories vary in artistry and content, depicting ex-Catholics and devout Jews, East Texan and Cincinnati-born Latinas, those who were remorseful or totally unapologetic, as well as activists, clinic escorts, doulas, and doctors. This is the real benefit of a comics anthology: no single personal account, mode of activism, nor larger history of abortion purports to be representative, especially in the U.S., especially now. Nor did the editors seek, like Johnson in her anthology, to produce a singular narrative frame that would regularize our affective response across examples.

Finally, let us consider the French-language comics mentioned at the outset. Alain and Désirée Frappier’s Le choix traces the history of the Veil Act alongside that of the author herself, an enfant non-désiré (unwanted child) who suffered familial neglect, isolation (due to severe asthma), and abuse at the hands of her father. Bolstered by a critical bibliography that retrieves the visual culture of the 1970s (like the MLAC poster mentioned above), Le choix pairs Désirée’s personal history as a MLAC militant with case studies of friends and friends’ mothers in postwar France, many of whom did not benefit from birth control (which was not legalized until the loi Neuwirth in 1967) or basic reproductive health education. The volume’s high-contrast, black-and-white imagery tends realist but occasionally, scenes appear as blurry vignettes, like those treating the 1974-5 French Assembly debate of the loi Veil. Simone Veil, the French Minister of Health at the time, stoically admitted to having an abortion, before a French National Assembly composed exclusively of men. This heroic, activist choice subjected her to horrifying sexist and antisemitic slander by her peers and the press.

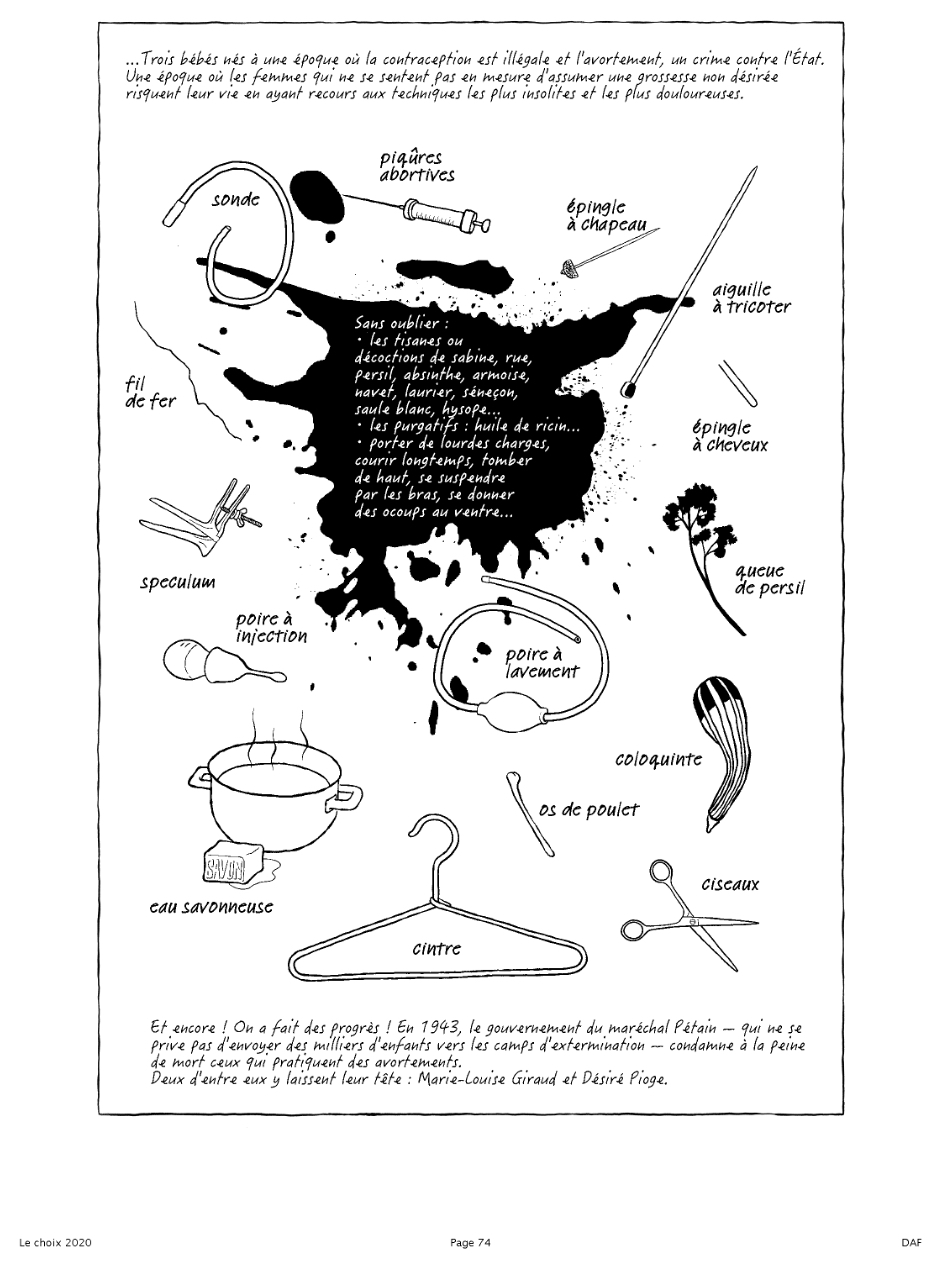

Alongside this polemical national debate, Désirée’s burgeoning activism grew out of witnessing the frequent complications (like septicemia) associated with clandestine abortions. Her realism is textual rather than visual, however, and her representations of physical pain and death tend to be indirect or metaphorical. See, for instance, a double page depicting the contents of a MLAC suitcase used to practice la méthode Karman or a panel depicting the many tools of clandestine abortion (Images 12 & 13). These instruments signal not only the serious medical procedures undertaken by self-trained activists, but the many, unspoken methods to which women and those with uteruses have traditionally resorted. The violence that a lack of access to birth control and abortion has inflicted on women is sometimes self-imposed, out of necessity.

Le choix is notable for its journalistic rigor. It draws on the strategies of documentary film making, integrating, for example, talking-head interviews with journalists and militants who supported legalizing abortion before the loi Veil, including Xavière Gauthier who has also published a memoir, and gynecologists Monique Valentino and Jacques Milliez, who describe treating women dying from clandestine abortions. [38] The volume depicts events like the 1972 Bobigny trial, during which the iconic feminist lawyer Gisèle Halimi defended a young woman accused of having had an abortion, and the 1973 Manifeste des 331, by doctors who openly performed abortions in Grenoble. [39]

Perhaps because it is steeped in BD reportage, some of Le choix’s most poignant moments are marked by visual metaphors, like the repeated image of a woman, seen from behind, soaking in the bath, which appears both inside the volume and on the cover art. During the Veil trial, Désirée’s mother casually reveals that she had had three abortions. Throughout the volume, the bath serves not only as a metonym for the mother’s depression (she is coldly distant and bathes alone incessantly) but also for clandestine abortions practiced in tubs (to accommodate bleeding). As Désirée explained in interviews, her mother did have abortions in the household bathroom, using a sonde or probe, the same method practiced in Ernaux’s case. Children, Désirée explains, bear enduring memories of a mother-in-crisis: “We should not oblige people to have children… Children bear the silence of their mothers, a silence that transforms into enduring sorrow.” [40] Bodily vulnerability is a generational trauma: unsayable abortions and silences about even basic birth control are carried from parent to child. An epigraph from the artist-illustrator couple’s website is also informative here:

Living memory is not born to serve ink. Rather, it has the vocation of being a catapult. It does not want to arrive at a safe haven but leave port. It does not renounce nostalgia, but it prefers hope, with its dangers, its inclement weather.

Eduardo Galeano, The Open Veins of Latin America. [41]

The Frappiers’ documentary comics do not pacify historical memory by fixing it in inked time and space. They revive that memory in the present. They activate nostalgia with stories of bygone MLAC activism or Veil’s heroism while nuancing and politicizing it. Désirée also documents how trauma marks us irrevocably, whether experienced directly or via familial osmosis. This is another affective reminder with political stakes: we must safeguard legal abortion not just for this generation, but for the next.

While Aude Mermilliod’s pastel-colored Il fallait que je vous le dise recounts more recent memories, it echoes Le choix’s investment in the lives of real women by narrating Mermilliod’s own abortion. Having become pregnant while using an IUD–a common theme across reproductive health albums–Mermilliod depicts with humor the emotional rollercoaster of being torn between her imagined future as a mother and the reality of her precarious living conditions. In a two-page spread, she appears in miniature before an enormous ultrasound, aghast at her pregnancy, as a tech demonstrates the growing fetus adjacent to an IUD. [42] (In Spooky Womb, British cartoonist Paula Knight draws a similarly alienating out-of-body experience, in which a woman sees, in her peripheral vision, her uterus winking at her. [43]) Mermilliod treats her abortion with bitter humor. The aggressive noise of the vacuum, figured by lettered onomatopoeia that gradually overwhelm the page, drowns out her internal monologue and snuffs out her ability to think. [44] The abortion’s aftermath–days of bleeding and a hastily abandoned one-night stand with a Ukrainian man–stretch our temporal sensibilities to suggest that abortion is not so much an event as a period of psychological and bodily vulnerability (much like Favre’s miscarriage). In this way, Mermilliod draws on a fundamental aspect of the medium, the ability to render time as space, or rather, to characterize the doubly “drawn-out” time experienced by a vulnerable woman.

Mermilliod’s beautiful, wordless watercolors of herself naked, bleeding, wandering in an idyllic forested landscape, or being massaged–an attention that returned her to her own body (“retour chez moi”)–conclude about halfway through the volume, before circling back to the framing narrative about her staged encounter with doctor-author Martin Winckler. This peach-colored frame story details Winckler’s coming-of-age as a feminist activist and gynecologist, and his burgeoning writing career (although neither Mermilliod’s album nor the comic adaptation of Le Choeur des femmes comments on his surprising choice to represent himself as an intersex woman). Winckler credits his politicization–really his humanization–to the women around him; nurses and doctors who pushed him to identify with women, and the many anonymous patients who consciously and unconsciously revealed to him their own vulnerable bodies. As the text across one sequence explains:

And of course, there was a little of every patient I met. Those whom I’ve forgotten, like those inscribed in red ink on my memory. / Those who smiled, those who cried, those who already had children, those who laughed nervously… / Those who were afraid, those who were angry with me, those who got on my nerves, those who were barely 13 years old… / Those who came from far away, those who said ‘thank you,’ those who were quiet, those who pulled on their hospital gowns, those who didn’t understand how this could have happened to them… [45]

Like Comics for Choice, Mermilliod and Winckler underscore the sheer diversity of women’s experiences and validate them. By “seeing from below,” they humanize the doctor and his extensive experience, modeling a physician who consciously empathizes with his patients.

The final French-language abortion album in this corpus, scriptwriter Tonino Benacquista’s collaboration with Florence Cestac, Des salopes et des anges, is more of a buddy comedy about MLAC and abortion than a complex historical or psychological investigation. The story follows three women who take a MLAC bus to London to get abortions: Maïté (22 years old) is a carefree woman whose pregnancy disrupts the plans of her career-minded boyfriend; Anne-Sophie (30) is a bourgeois housewife with two children and a conservative Catholic husband, pregnant with her lover’s child; and Odile is a free spirit MLAC militant who remains in London after the procedure. Cestac’s iconic quirky Muppet-like figures–known for their voluptuous noses and minimalist mouths–are depersonalized types (the wayward youth, the militant, the bourgeoise) that are in keeping with the volume’s quaint, milk toast tonality and its occasional groaner jokes. If light-hearted, the album makes two clear conceptual claims: figuring abortions as something that no woman need justify and as a site of sisterly bonding (the trio meets again annually for the rest of their lives).

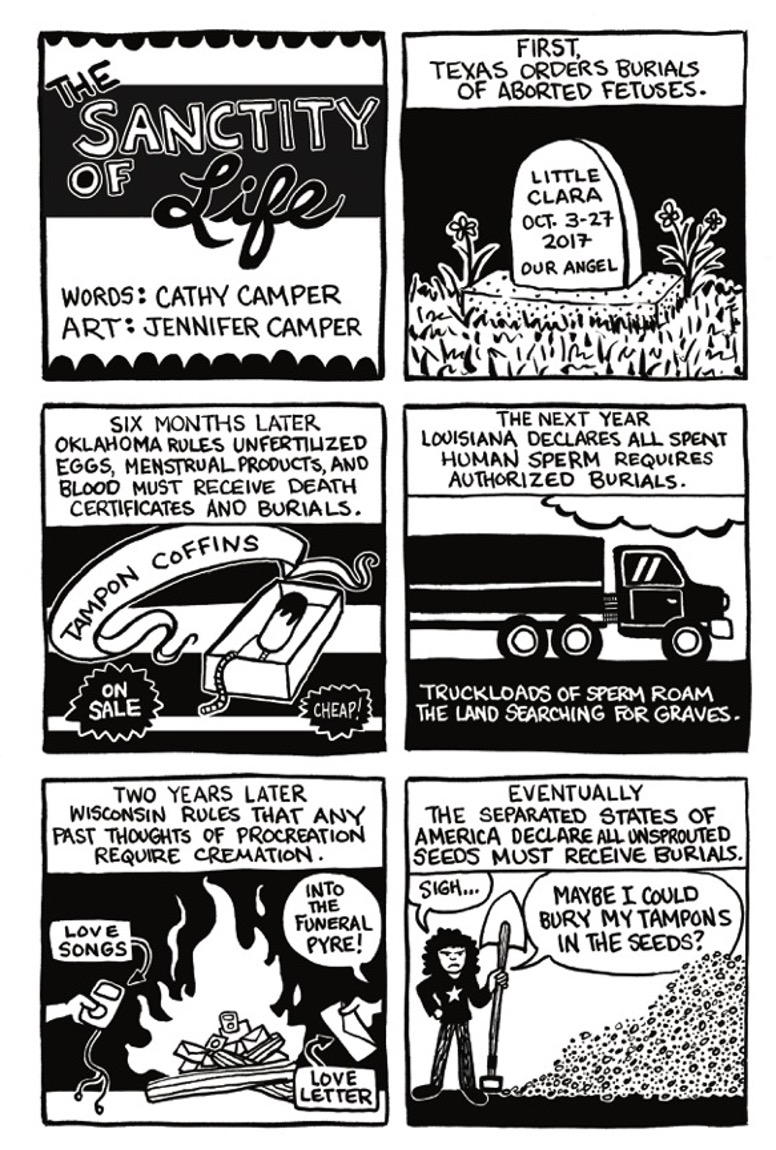

If the volume succumbs to middling comic plotlines–Maïté’s boyfriend, Jean-Paul, chases her bus and gets trapped in a hippie van–it also opens with a beige-colored prehistory of abortion dating back to Babylonia. Here, Cestac’s drawings, like political cartoons, harness the full communicative power of the single-panel frame. While the imagery is distinctly cartoonish, in frame after frame, faceless, anonymous women–more vulnerable bodies–are hanged, poisoned, put to death, die from infection, or bleed out from botched surgeries. Cestac’s bitter humor recalls similarly dark cartoons published in the Washington Post or Comics for Choice. Consider Jennifer Camper’s “horror show” of objects used in illegal abortions (like the Frappiers’ own) or a sequence in which the artist, based on text by Cathy Camper, follows the Texas law requiring the burial of aborted fetuses to its satirical endpoint: it first depicts the burial of fetuses, then menstrual products and sperm, and, finally, past thoughts (Image 14). Sometimes the only way to document the true violence inflicted on women by State and society is through humor. [46]

This essay hardly exhausts the rich field of reproductive health and abortion comics but a consistent thread runs throughout: the vulnerable body asks for an affective response. Abortion comics, and comics writ large, have the peculiar strength of bearing witness, through the artist’s vision and hand, to the felt experiences that make us human. Living with fertility should be mundane but denying access to basic healthcare, contraception, and abortion makes it anything but.

As a visual and textual medium, comics are polyphonic, allowing different and conflicting voices, emotions, and registers to somehow coexist. This essay implicitly demonstrates a distinct preference for non-fiction or autobiographical narratives, which necessarily play with polyphony as they navigate between testimony, history, journalism, and drawn art. In this corpus, drawn imagery often serves to imagine or abstract what cannot be said. But sometimes even a single frame–like Cestac’s woman seated in a pool of her own blood–speaks in a way that narratives cannot.

As a pedagogical exercise, I would encourage students to read across languages and cultures, as I have done here. Juxtaposing examples from France, the U.S., and Canada allows students to track how similar histories played out differently, sometimes to catastrophic ends, in parallel Western nation-states. This comparative view especially shines a light on the slow violence imposed on vulnerable bodies: whether it be conventions of gynecological practice or the complex and constantly changing mechanisms for accessing care. Documentary comics, especially Le choix and Mermilliod’s albums, or comic anthologies, are distinctly well suited to diversifying human experience. They highlight how different individuals, across generations, practically and psychically managed reproductive crises, in varying socio-cultural contexts. Yet, just as reproductive health comics disproportionately highlight white, heterosexual women–except perhaps for Comics for Choice or Menopause: A Comic Treatment–this corpus is also distinctly Western. Consider this testimony, in absentia, to the utterly unspeakable clandestine abortions, still practiced in most of the world. When will their lives and bodies be drawn? As it stands, these international, reproductive histories often appear embedded in others, but they, too, deserve to be drawn on their own terms. [47]

If these artists testify to, or imagine, the violence of history and the State, they do so with consistent philosophical and ethical stakes. They endlessly reiterate what we should not have to debate: that women and people with uteruses deserve to make health decisions, safely and comfortably, on their own terms. Bodily and psychic autonomy prevails, first and foremost. This is a radical rejection, not just of conservative male politicians who relentlessly inject the State into our bodily lives, but the subtle ways in which medical institutions patronize us or dictate our behaviors. These authors also polemically reject pre-established cultural scripts or narrative conventions. Many of them never have children and flatly refuse any similarly “happy ending” to justify abortion. Most also deny us sublimations that would transform a fundamentally bodily experience (and memory) into something else. This is a distinctly literary form of activism: refusing to write stories the way that (some) people want to read them. They also narrativize and make visible the complexities of a bodily experience that French and North American cultures have too long obscured–and continue to silence.

Bibliography

Marguerite Abouet, Aya de Yopougan, with drawings by Clément Oubrerie (Paris: Gallimard, 2005-2010)

— Aya de Youpougan: Life in Yop City, with drawings by Clément Oubrerie (Montréal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2012)

Herculine Barbin, Herculine Barbin: being the recently discovered memoirs of a nineteenth-century hermaphrodite (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980)

— Mes souvenirs: histoire d’Alexina-Abel B (Paris: La Cause des Livres, 2008)

Tonino Benacquista, Des salopes et des anges, with illustrations by Florence Cestac (Paris: Dargaud, 2021)

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006)

— Who is my Mother? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2013)

Clément Baloup, Mémoires du Viet Kieu (Antony (Hauts-de-Seine): La Boîte à bulles, 2012-2020)

— Vietnamese Memories (Los Angeles, CA: Life Drawn, an imprint of Humanoids Inc., 2018)

Comics for Choice. No copyright or publication date. http://comicsforchoice.com/about.

Comics for Choice: Illustrated Abortion Stories, History, and Politics, Eds. Hazel Newlevant,

Whit Taylor, and OK Fox (Hazel Newlevant, 2017)

Shelby Criswell, Queer as all Get Out (Brooklyn, NY: Street Noise, 2021)

Marie Dubois, Un bébé si je peux (Paris: Massot, 2021)

Emma, Un autre regard: trucs en vrac pour voir les choses autrement (Paris: Massot, 2017)

— The Mental Load, A Feminist Comic (New York; Oakland; London: Seven Stories Press, 2018)

Annie Ernaux, L’événement (Paris: Gallimard, 2000)

— Happening, trans. Tanya Leslie (New York; Oakland; London: Seven Stories, 2019)

Joyce Farmer, “Joyce Farmer: Day 4,” The Comics Journal, May 12, 2011. https://www.tcj.com/joyce-farmer-day-four/.

Cléa Favre, Ce sera pour la prochaine fois (Lausanne: Éditions Favre, 2022)

Désirée and Alain Frappier, “Bios,” author website. https://dafrappier.weebly.com/bios.html

— Dans l’ombre de Charonne (Paris: Éditions Mauconduit, 2012)

— Le choix (Paris: Steinkis, 2020)

Agatha French, “How I Got Through My Miscarriages,” New York Times, November 22, 2022, updated November 23, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/22/magazine/miscarriage-grief.html.

Xavière Gautier, Avortées clandestines (Paris: Éditions Mauconduit, 2015)

Gendry-Kim, Keum Suk, Grass, translated by Janet Hong (Montréal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2019)

The Graphic Medicine Manifesto, Eds. Eds. MK Czerwiec, Ian Williams, Susan Squier, Michael

J. Green, Kimberly R. Myers, Scott T. Smith (University Park, Penn.: University of Pennsylvania UP, 2015)

Graphic Medicine International Collective, copyright 2007-2023, https://www.graphicmedicine.org/why-graphic-medicine/

Graphic Reproduction: A Comics Anthology, Ed. Jenell Johnson (University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012)

Leah Hayes, Not Funny Ha-Ha: A Handbook for Something Hard (Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books, 2015)

Magali Le Huche and Gwendoline Raisson, Mères Anonymes (Paris: Dargaud, 2013)

No Author, “L’Assemblée nationale vote pour l’inscription du droit à l’avortement dans la Constitution,” Le Monde with Agence-France-Press, November 24, 2022. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2022/11/24/l-assemblee-nationale-vote-pour-l-inscription-du-droit-a-l-avortement-dans-la-constitution_6151455_823448.html.

Brice Laemle and Cécile Bouanchaud, “PMA pour toutes: que change la loi de bioéthique dans la procédure?” Le Monde, June 29th, 2021.

Anne Linton, Unmaking Sex: The Gender Outlaws of Nineteenth-Century France (Cambridge, UK; New York, NY: Cambridge, 2022)

Lucy Knisley, Go to Sleep (I Miss You) (New York: First Second, 2020)

— Kid Gloves (New York: First Second, 2019)

Maia Kobabe, Gender Queer (Portland, Or.: Oni Press, 2019)

Menopause: A Comic Treatment, Ed. M.K. Czerwiec (RN, MA) (University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020)

Rachel Mesch, Before Trans: Three Gender Stories From Nineteenth-Century France (Stanford, Ca.: Stanford, 2020)

Aude Mermilliod, Le Choeur des femmes (Brussels: Le Lombard, 2021)

— Il fallait que je vous le dise (Brussels: Casterman, 2019)

Natalie Pendergast, Partum Me (Wolfville, Canada: Conundrum Press, 2023)

Lucie Servin, “L’avortement en mémoire du corps des femmes,” L’Humanité, Feb. 23rd, 2015. https://www.humanite.fr/culture-et-savoirs/avortement/lavortement-en-memoire-du-corps-des-femmes-566361.

Lilli Sohn, Vagin tonic (Brussels: Casterman, 2018)

— Vagina Love: A User’s Manual (Brooklyn, NY: Street Noise, 2022)

Bishakh Som, Spellbound (Brooklyn, NY: Street Noise, 2020)

AK Summers, Pregnant Butch: Nine Months Spent in Drag (New York: Soft Skull Press, 2013)

Eszter Szép, Comics and the Body (Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State UP, 2020), 6-10.

Teresa Wong, Dear Scarlet (Vancouver, British Columbia: Arsenal Pulp, 2019)

Notes

[1] All images are copyrighted and used with the explicit permission of artists and/or their publishers, except for a few that are public domain. The Dobbs decision overturned both Roe v. Wade (1973), which guaranteed that abortion was a constitutional right, and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), which allowed states to regulate aspects of abortion outside of national law.

[2] See also Annie Ernaux, Happening, trans. Tanya Leslie (Seven Stories, 2019).

[3] This reading was part of the annual Nuit des idées, see Villa Albertine’s website: https://nightofideas.org/new-york/schedule/#schedule-4963.

[4] A June 2021 bioethics law expanded access to PMA procedures, like IVF and sperm donations, to lesbian couples and single ciswomen but excluded transmen. See Laemle and Bouanchaud.

[5] See LeMonde with AFP, “L’Assemblée nationale vote pour l’inscription du droit à l’avortement dans la Constitution.” Published Nov. 24, 2022. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2022/11/24/l-assemblee-nationale-vote-pour-l-inscription-du-droit-a-l-avortement-dans-la-constitution_6151455_823448.html

[6] Michael Cavna, “Cartoonists Passionately take on the Supreme Court’s abortion decision,” The Washington Post, June 27, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/comics/2022/06/27/cartoons-abortion-supreme-court-dobbs/. Hannah Good, “These Comics Show There is NO Typical Abortion Story,” The Washington Post, Oct. 31st, 2022. Updated Nov. 1, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/interactive/2022/abortion-comics/.

[7] See the WeTestify website, updated April 4, 2021, https://www.wetestify.org/stories, which provides information about the storytellers and illustrators, as well as an interactive map of over 200 stories of abortion. See also the Comics for Choice website.

[8] For discussions of various aspects of reproductive health, see edited volumes like Johnson’s Graphic Reproduction: A Comics Anthology (2012), which includes reprinted feminist comics by Joyce Farmer and others, alongside new, original work, or M.K. Czerwiec’s Menopause: A Comic Treatment (2020), which includes graphic artwork by well-known artists like Lynda Barry, Roberta Gregory, Ellen Forney, A.K. Summers, Joyce Farmer, and Jennifer Camper. See Lili Sohn’s Vagin tonic (2018), translated as Vagina Love: A User’s Manal (2022), for a catch-all pedagogical manual about vaginas, which includes discussions of toxic shock and endometriosis. The insertion of a stérilet (IUD) is described in detail in Aude Mermilliod’s Le Choeur des femmes (2021). Farmer’s contribution to Menopause depicts a postmenopausal woman pleasuring herself with a vibrator, see Farmer, “Antique Restoration: Do Menopausal Women Even Get Horny?” Menopause: A Comic Treatment 124-128.

[9] Excerpts of this comic are reprinted as Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli, “Abortion Eve,” Graphic Reproduction 17-54. Farmer wrote an essay about the comic and her own abortion, see Farmer, “Joyce Farmer: Day 4,” n.p.

[10] Diane Noomin, an editor of Twisted Sister, later documented her own miscarriages, see Noomin, “Baby Talk: A Tale of Four Miscarriages” (1994). For a recent review of the strip, see French, “How I Got Through My Miscarriages,” n.p.

[11] For a discussion of affective vulnerability, see Szép, Comics and the Body 6-10. Szép does not use Kominsky-Crumb or Doucet as examples, but focuses on other Anglophone artists like Lynda Barry, Ken Dahl, Joe Sacco, Miriam Katin, and Katie Green.

[12] For the website of the international collective, which includes a charter, testimonies, and list of members, see https://bdegalite.org/.

[13] See Emma, Un autre regard, n.p.and The Mental Load: A Feminist Comic 32-41, 54-69. For other discussions of episiotomies, see Sohn, Vagina Love 198.

[14] Emma, Un autre regard n.p. and The Mental Load 2-22, 71-82, 145-158.

[15] Graphic medicine as a subfield was founded in 2007 by Dr. Ian Williams. The Graphic Medicine International Collective, founded in 2019, is a non-profit organization that brings together comics and medical professionals. It began after the publication of The Graphic Medicine Manifesto (2015) but has been organizing an annual conference since 2010. See the website of the Graphic Medicine International Collective.

[16] “Introduction,” Graphic Medicine Manifesto, n.p.

[17] Jenell Johnson, “Introduction,” Graphic Reproduction 2-16, especially 15, and 4-7.

[18] Johnson, “Introduction,” 2, 10.

[19] See Paul Knight, “X-Utero: A Cluster of Comics,” Graphic Reproduction 86-88. See Pendergast’s forthcoming Partum Me and her strips at her Instagram handle @nataliebpendergast.

[20] See Barbin, Mes souvenirs and Barbin, Herculine Barbin. See also Linton, Unmaking Sex and Mesch, Before Trans. Sohn’s Vagina Love also warns against pediatric intersex surgeries, see Vagina Love 154-5.

[21] Mermilliod, Le Choeur des femmes 86, 88-89, 90-91.

[22] Le Huche and Gwendoline Raisson, n.p.

[23] Bechdel is incidentally a great reader of late 19th-century and early 20th-century French literature, sexuality, and psychiatry, causally inserting historical (pathologizing) psychiatric terms like inversion in her works.

[24] Summers 81.

[25] Ibid 95.

[26] Ibid 110.

[27] Johnson laments the lack of BIPOC authors in her anthology, attributing it in part to her inability to commission new comics. See Johnson, “Introduction,” 14, note 15.

[28] Mermilliod, Le Choeur des femmes, 79.

[29] Sohn, Vagina Love 22-23, 27.

[30] Sohn, Vagina Love 21.

[31] Sohn, Vagina Love 24.

[32] Sohn’s otherwise highly detailed overviews–of vaginal anatomy, menstruation, menopause, birth control methods, etc.–includes one page that mentions abortion in passing, with no explanation of the methods and a link to Planned Parenthood. See Sohn, Vagina Love 174.

[33] See “Jane,” written by Rachel Wilson and art by Ally Shwed, Comics for Choice 41-51.

[34] See the statement on the volume’s website, “About us.”

[35] For instance, see “My Voice, My Choice,” written by a Black woman from Chicago’s South Side, Brittany Mostiller, with art by Lilly Taing; “The Outcasts,” written by Heidi Williamson with art by Julia Krase, set in a dystopian Atlanta in 2037, where women are jailed for abortion, miscarriages, and other fertility issues; and “October” is written by the trans artist Kris Louis, Comics for Choice 60-67, 94-104, 144-152. Menopause: A Comic Treatment also represents a diversity of genders and sexualities, including a comic by Black genderqueer artist Ajuan Mance (“Any Day Now,” 66-73) and by transmasculine artist KC Councilor (“Cycles,” 74-77).

[36] See “Undue Burdens,” written and drawn by Hallie Jay Pope, Comics for Choice 51-55.

[37] For mentions of Brown or Davis’s filibuster, see “They Called Her Dr. D,” written by Dr. Cynthia Greenlee with art by Jaz Malone; “The Unruly Mob,” written by Lindsay Rodriguez with art by Lucy Haslam; and “Coming Out: A Texas Abortion Story,” written by Sam Romero with art by Erin Lux, Comics for Choice 22-35, 68-76, 77-87.

[38] See Gauthier.

[39] The Frappiers have produced other BD reportages, notably a volume about the 1962 Charonne massacre, during which several anti-Algerian War activists were crushed in the Charonne metro station. See Désirée and Alain Frappier, Dans l’ombre de Charonne.

[40] “On n’oblige pas les gens à avoir des enfants…. Les enfants portent les silences de leur mère, des silences qui se transforment en chagrins qui durent.” See Servin for an interview with Desirée Frappier, my translation.

[41] The epigraph in French is from Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano’s Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971), see Désirée and Alain Frappier’s website, my translation.

[42] Mermilliod, Il fallait que je vous le dise 33-34, my translation.

[43] Paula Knight, “Excerpts from Spooky Womb,” Graphic Reproduction 69-80, 70.

[44] Mermilliod, Il fallait que je vous le dise 52-53.

[45] “Et bien sûr, il y avait un peu de chaque patiente rencontrée. Celles que j’ai oubliées comme celles inscrites au fer rouge dans ma mémoire. / Celles qui souriaient, celles qui pleuraient, celles qui avait déjà des enfants, celles qui riaient nerveusement… / Celles qui avaient peur, celles qui m’en voulaient, celles qui me tapaient sur les nerfs, celles qui avaient à peine 13 ans… / Celles qui venaient de loin, celles qui disait ‘merci’, celles qui se taisaient, celles qui tiraient sur les chemises de nuit, celles qui ne comprenaient pas comment ça avait bien pu leur arriver…” Mermilliod, Il fallait que je vous le dise 154-55, my translation.

[46] See “The Sanctity of Life,” written by Cathy Camper with art by Jennifer Camper, Comics for Choice 21, 105.

[47] For example, see Marguerite Abouet’s multi-volume series, Aya de Yopougan (2005-2010), set in Ivory Coast in the 1970s, focuses on the lives of young women, who are sexually active, but without basic reproductive education. See also Clément Baloup’s Mémoires du Viet Kieu (2012-2020), which tells stories of women living in the Vietnamese diaspora in France and the US, some of whom confront the lifelong trauma of rape in American war camps. Finally, see Keum Suk Gendry-Kim gorgeous Grass (2019), which recounts the life of a Korean comfort woman, in sexual slavery organized by the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII.