Siri Suh, Brandeis University

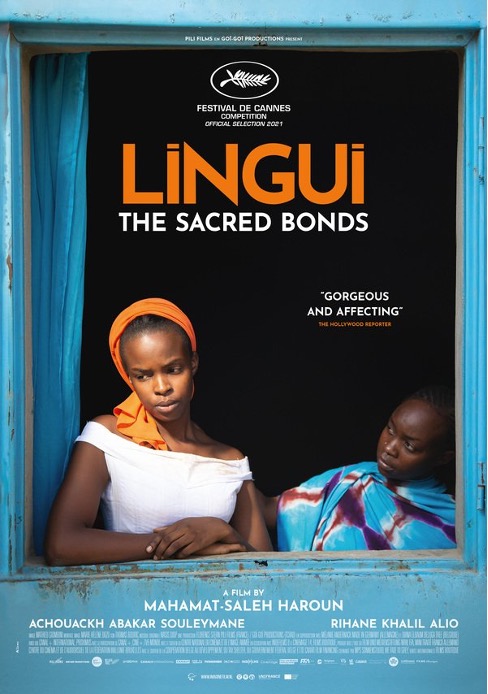

Lingui: The Sacred Bonds offers a vivid portrayal of the dismal realities of seeking abortion in Chad, where legal services are restricted to cases of fetal malformation, rape, incest, or when pregnancy threatens a woman’s life or health. The film follows Amina, a hardworking single mother, in her desperate quest to help her 15-year-old daughter, Maria, terminate an unwanted pregnancy. The search begins in the formal healthcare sector, where Amina and Maria consult with a doctor in a government hospital. Although the physician refuses to perform the abortion at the hospital, saying it’s too professionally risky, he indicates that he can do it at a private clinic, for 1,000,000 Francs (about 1600 U.S. dollars). Discouraged by the exorbitant price, Amina widens her search to informal practitioners, including a traditional healer who not only performs abortions in her home but also female genital circumcision.

Amina and Maria’s story is all too familiar in sub-Saharan Africa, where 92% of all women are subject to restrictive abortion laws, with the consequence that nearly all abortions in sub-Saharan Africa (77%) are classified as unsafe. [1] Although some women consult formal and informal practitioners for abortion services, others attempt to self-induce by ingesting antibiotics, aspirin, malaria prophylaxis, bleach or ground glass, or by inserting catheters, roots or other objects into the uterus through the vagina. With at least 6.2 million abortions occurring in sub-Saharan Africa every year [2], health systems, patients, and their families pay a heavy price for treating emergency complications of unsafe abortion, or post-abortion care, estimated at 171 million U.S. dollars every year [3]. Studies in Nigeria [4] and Zambia [5] have found that women pay morefor post-abortion care than for safe abortions. In Senegal, where I do research on post-abortion care, the average out-of-pocket cost of post-abortion care is 94 U.S. dollars (which amounts to 15% of women’s average salary), and only an estimated third of patients receive pain medication. [6] Post-abortion care services at government hospitals are not only exorbitantly priced and of poor quality, but they also open the door to criminalization, especially for young, unmarried, low-income women seeking services. [7]

Many details in Lingui’s portrayal of the social and economic drivers of clandestine and frequently unsafe abortion resonate with ethnographic research on contraception and abortion in Africa. While modern contraceptive methods are ostensibly available in public and private health facilities, regular contraceptive use may be challenging due to gendered expectations around sexuality and childbearing within marriage. For a young, unmarried woman like Maria, requesting emergency contraception from a midwife in a government clinic or a pharmacist might invite unsolicited interrogation into her sexual life, and even notification of family members. In Niger, anthropologist Hadiza Moussa found that married women often preferred to terminate ill-timed pregnancies rather than negotiate regular contraceptive use with husbands, in-laws, and health workers. [8] Her findings resonate with a recent study in 36 low- and middle-income countries that found a greater likelihood of abortion among married women. [9] Although abortion is not an uncommon reproductive practice, it is deeply stigmatized because it signals a rejection of motherhood, as well as a subversion of male authority over women’s fertility. [10] Women known to have had abortions may be ostracized from their families and communities, or subjected to violence and financial abandonment. Yet, ethnographic research shows that seeking abortion, even under unsafe circumstances, may be preferable to single motherhood, because abortion permits one to hide inappropriate sexuality, prior to or outside of marriage. [11, 12] For precisely these reasons, Amina was banished from her family when she became pregnant before marriage.

Yet, ethnographic research shows that seeking abortion, even under unsafe circumstances, may be preferable to single motherhood, because abortion permits one to hide inappropriate sexuality, prior to or outside of marriage.

Ethnographic research has found that diverse social networks are crucial to accessing abortion resources and information. [13] A recent study in Burkina Faso found that low-income women with smaller social networks were more likely to experience price gouging by abortion providers and brokers of services and information. [14] Lingui illustrates this price-gouging when the physician initially proposes an exorbitant sum for performing an abortion in a private clinic. Although Amina’s neighbor refuses her offer of sex in exchange for money to pay for Maria’s abortion, ethnographic research suggests that low-income women are particularly vulnerable to sexual coercion by abortion practitioners and brokers.

Lingui also offers important insight into technical practices, professional dilemmas, and the variety of practitioners who provide abortion services in sub-Saharan Africa. The physician at the government hospital initially refuses to provide an abortion on the premises but arranges a procedure at a private facility aptly called “Liberty Clinic.” A traditional healer assures Amina that she regularly performs abortions, among other procedures, in her home. Toward the end of the film, Maria receives abortion services from a nurse or midwife in a small clinic operated from her residence. While the practitioner does not specify the procedure, the display of metal surgical tools suggests that she performed dilation and curettage, which is less safe than other surgical methods like manual or electric vacuum aspiration. When she hands Maria a certificate indicating that she received treatment for obstetric complications, we witness the enormously influential role played by health professionals in determining women’s fates in the aftermath of abortion. By establishing Maria’s non-pregnant status, the certificate permits her to return to school. Although the certificate acknowledges that she was pregnant, it offers a more socially acceptable reason for pregnancy loss than induced abortion: miscarriage.

My research on post-abortion care in Senegal shows that health workers–and midwives in particular–regularly record suspected cases of illegal abortion as miscarriage not only to protect their patients but also themselves from the police. [15] When police raid the Liberty Clinic where Maria is staying overnight, in advance of a scheduled abortion, the scene illustrates the ever-present danger of criminalization for health workers who provide abortion services and, in Senegal, even the legitimate reproductive health service of post-abortion care. The Senegalese health workers I interviewed were aware that at any moment police officers could arrive at the hospital to conduct interrogations about suspected cases of illegal abortion and to requisition related medical documents. When the state prosecutes women for illegal abortion, health workers are sometimes required to provide expert testimony.

Finally, Lingui traces a series of gendered and classed institutional failures that increase the likelihood of unsafe abortion for socially and economically vulnerable women like Amina and Maria. Chad’s abortion law, a remnant of the French colonial period, abandons the poorest women to clandestine and frequently unsafe abortion practices. Although abortion is permitted in cases of rape, women may be reluctant to report such assaults to the police. Maria’s automatic expulsion from school because of her pregnancy evokes additional institutional discrimination against girls and women. The principal seems more concerned with protecting the school’s “image” than inquiring after Maria’s immediate health and safety or negotiating her return to school. Similarly, families may fail to protect and support women and girls with premarital pregnancies. We know that Amina’s family banished her when she became pregnant and, when she learns of Maria’s pregnancy, Amina responds with anger by hitting her daughter. Nor are religious leaders necessarily reliable sources of support. Although Amina’s neighborhood Imam seems to be aware that she is struggling, his expressions of concern are limited to chastising her for not attending the mosque more regularly.

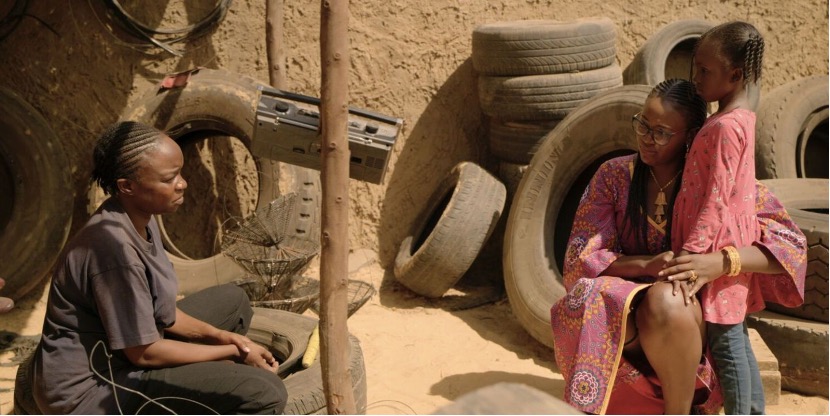

The most reliable forms of support for women in times of need come from other women, through the lingui or “sacred bonds” of sisterhood from which Haroun’s film takes its title. Amina can finally afford to pay for a safe abortion for Maria when her sister, Fanta, insists that Amina take and sell her gold jewelry. When the Liberty Clinic is raided by police, a nurse hurriedly refers Maria to another health worker for help. After that health worker performs the abortion, she refuses Amina’s payment, essentially providing the service (including the medical certificate of miscarriage) at no cost. Despite Amina’s initial fury over Maria’s pregnancy, she devotes herself to helping her daughter identify a safe abortion provider. Later, Maria helps guide her mother home after Amina confronts the neighbor who raped her daughter. When Amina learns from Fanta that her niece may have to undergo circumcision, at her father’s insistence, she refers her sister to the traditional healer who provides fake circumcision services. Perhaps one of the most subversive scenes in the film unfolds as Fanta’s husband generously rewards the women in attendance at his daughter’s circumcision ceremony. Amina and Fanta exchange sly grins across the courtyard as he pompously throws wads of cash to the ululating guests, blissfully unaware that he has been duped. And if Lingui focuses overwhelmingly on the strength of women’s relational commitments, we see at least one man contribute to the “sacred bonds”: a young man who saves Maria from drowning when she tries to commit suicide, accompanies her home, and refuses Amina’s offer of payment with the explanation that he was simply “doing his duty.”

Although Lingui offers devastatingly realistic images of abortion practices and itineraries in Africa, it is less attentive to other important social, economic, and technological dimensions of abortion. First, the film glosses over important class differences that significantly shape abortion networks and outcomes. Amina is a single mother who earns a living by fashioning iron stoves that she sells for 3000 Francs (a little under 5 U.S. dollars), and lives with her daughter in a low-income neighborhood on the outskirts of N’Djamena, where open sewage trickles onto the unpaved streets. Yet, her daughter attends the same school as a young woman who can host a birthday party at a fancy hotel, where champagne is available alongside soft drinks. If Maria could realistically move in the same social circles as the wealthy birthday girl, the abortion information available through those networks, facilitated by social media apps like WhatsApp, might obviate the need to involve her mother. Ethnographic research suggests that wealthy women have greatest access to social networks of friends, family members, health workers, and abortion brokers that are critical to the exchange and circulation of information about abortion providers and medications. [16] Additionally, with the increasing availability of abortion medications like misoprostol in formal and informal healthcare sectors in cities like N’Djamena, more women are opting for self-administered, pharmaceutical approaches that offer more discretion–and greater safety if used correctly– than surgical procedures performed by health workers. At least one brand of misoprostol, called Misodia, is registered in Chad, and thus available for sale in pharmacies and health facilities.

Sadly, available epidemiological and demographic data suggest that, when it comes to abortion, happy endings for young women like Lingui’s Maria are rare. Young, low-income women face a particularly high risk of death or complications related to abortion, precisely because they lack the financial resources and social capital required to access safer methods. A young woman of Maria’s class background could probably not afford surgical services in a high-end clinic with amenities for overnight stays. She would be more likely to swallow bleach, insert roots or other objects into her uterus, or throw herself off a roof or down some stairs to terminate her pregnancy. If she survived, she might well require emergency post-abortion care services, available but not necessarily affordable at a government hospital. If she could pay for that post-abortion care, she would face intense questioning by health workers, and possibly arrest and incarceration. Finally, even if she managed to evade criminalization, she might face diminished prospects for a secure marriage because her fertility had been impaired by unsafe procedures.

Released in 2021, Lingui reminds audiences in the global North and South that access to safe abortion care cannot be taken for granted. In 2012, Savita Halavanappar died of a septic miscarriage at a hospital in Ireland because doctors refused to treat her while her fetus was still alive. In 2015, Anna Yocca was transported to a hospital emergency room in Tennessee, U.S. after using a coat hanger in her bathtub to terminate a pregnancy of twenty-four weeks. Following the 2023 reversal of Roe v. Wade in the U.S., an estimated 29% of American women find themselves living under prohibitions or severe restrictions on access to abortion. [17] And yet, decades of epidemiological evidence from the global North and South make clear that the availability of safe, legal abortion reduces risks of death and injury related to unsafe abortion. Restrictive abortion laws do not protect women’s health. Their sole purpose is to control women’s sexuality and reproduction. In countries like Chad and the U.S., the most vulnerable women pay the high cost of such laws not only with precious time and money but, too often, with their bodies and their lives.

Mahamet-Saleh Haroun, Lingui: The Sacred Bonds (2021) France, Chad, Germany, Belgium. 87 min. Ad Vitam (2022)

Notes

[1] Akinrinola Bankole et al., “From Unsafe to Safe Abortion in Sub-Saharan Africa: Slow but Steady Progress,” Guttmacher Institute, August 24, 2022, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/from-unsafe-to-safe-abortion-in-subsaharan-africa.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Michael Vlassoff et al., “Estimates of Health Care System Costs of Unsafe Abortion in Africa and Latin America,” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 35, no. 03 (2009): 114–21, https://doi.org/10.1363/3511409.

[4] Stanley K. Henshaw et al., “Severity and Cost of Unsafe Abortion Complications Treated in Nigerian Hospitals,” International Family Planning Perspectives 34, no. 01 (2008): 040–051, https://doi.org/10.1363/3404008.

[5] Divya Parmar et al., “Cost of Abortions in Zambia: A Comparison of Safe Abortion and Post Abortion Care,” Global Public Health 12, no. 2 (2015): 236–49, https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1123747.

[6] Colin Baynes et al., “Understanding the Financial Burden of Incomplete Abortion: An Analysis of the out-of-Pocket Expenditure on Postabortion Care in Eight Public-Sector Health Care Facilities in Dakar, Senegal,” Global Public Health 17, no. 9 (2021): 2206–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1977972.

[7] Siri Suh, Dying to Count: Post-Abortion Care and Global Reproductive Health Politics in Senegal (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2021).

[8] Hadiza Moussa, Alice J. Kang, and Barbara M. Cooper, Yearning and Refusal an Ethnography of Female Fertility Management in Niamey, Niger (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2023).

[9] Djibril M. Ba et al., “Factors Associated with Pregnancy Termination in Women of Childbearing Age in 36 Low-and Middle-Income Countries,” PLOS Global Public Health 3, no. 2 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001509.

[10] Anuradha Kumar, Leila Hessini, and Ellen M.H. Mitchell, “Conceptualising Abortion Stigma,” Culture, Health & Sexuality 11, no. 6 (2009): 625–39, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050902842741.

[11] Wolf Bleek, “Avoiding Shame: The Ethical Context of Abortion in Ghana,” Anthropological Quarterly 54, no. 4 (1981): 203, https://doi.org/10.2307/3317235.

[12] Jennifer Johnson-Hanks, Uncertain Honor: Modern Motherhood in an African Crisis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

[13] Clémentine Rossier, “Abortion: An Open Secret? Abortion and Social Network Involvement in Burkina Faso,” Reproductive Health Matters 15, no. 30 (2007): 230–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-8080(07)30313-3.

[14] Seydou Drabo, “The Domestication of Misoprostol for Abortion in Burkina Faso: Interactions between Caregivers, Drug Vendors and Women,” Global Maternal and Child Health, 2022, 57–71, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84514-8_4.

[15] See Suh.

[16] See Drabo.

[17] Liza Fuentes and Guttmacher Institute, “Inequity in US Abortion Rights and Access: The End of Roe Is Deepening Existing Divides,” Guttmacher Institute, January 25, 2023, https://www.guttmacher.org/2023/01/inequity-us-abortion-rights-and-access-end-roe-deepening-existing-divides.