Mary Lynn Stewart

Simon Fraser University (Emerita)

In 2014, two full-length bio-pictures about one of the most famous couturiers of the last half of the twentieth century opened in Paris. The first of these releases, Yves Saint Laurent, is available on DVD and Blue Ray at Amazon (though some versions are in a European format that can be viewed on zone-free players or on a computer). A subtitled version has been shown at some North American film festivals. The second film, Saint Laurent, is slotted for international release by Sony Pictures Classics. The film may not be widely distributed in cinemas because it is two and a half hours long and contains scenes of homoerotic practices in the age before AIDS. At more than one showing in Paris, audience members left the cinema an hour or more before the film ended. If it is released in North America, it will certainly receive an R or even more restrictive rating. Anyone wanting to show the film to undergraduates will have to warn students of the potentially disturbing content. An alternative would be to use clips, since Saint Laurent is packed with scenes that would encourage classroom discussion.

Comparisons and controversy followed the release of the two pictures. One point of comparison, and the most significant source of controversy, derives from the attitude of Pierre Bergé (b.1930) the long-time business and life partner (and eventually husband) of Saint Laurent. Whereas Bergé opened his extensive archives and lent vintage designs to the director of Yves Saint Laurent, Jalil Lespert, he tried to stop the production and distribution of Saint Laurent, directed by Bernard Bonello. Lespert is best known as the lead in Laurent Cantet’s Human Resources (1999) about worker lay-offs while Bonello directed the racy and controversial L’Apollonide or House of Tolerance of 2011. Lespert presents a more sympathetic version of Saint Laurent and Bergé than Bonello, although neither director is sycophantic about either of their main characters. Both films portray Yves as shy, sensitive and immensely talented, charming to the women who surrounded him at work and at play. They also show him as a perpetual adolescent, who petulantly, even perversely hurt the men and women in his life, thus supporting Yves’ own assessment that he “was not so nice.” Bergé is depicted as a protective and almost paternal lover, although Bonello pays more attention to the shrewd businessman who built the Yves Saint Laurent couture house both around the designs and the designer’s public image.

Comparisons and controversy followed the release of the two pictures. One point of comparison, and the most significant source of controversy, derives from the attitude of Pierre Bergé (b.1930) the long-time business and life partner (and eventually husband) of Saint Laurent. Whereas Bergé opened his extensive archives and lent vintage designs to the director of Yves Saint Laurent, Jalil Lespert, he tried to stop the production and distribution of Saint Laurent, directed by Bernard Bonello. Lespert is best known as the lead in Laurent Cantet’s Human Resources (1999) about worker lay-offs while Bonello directed the racy and controversial L’Apollonide or House of Tolerance of 2011. Lespert presents a more sympathetic version of Saint Laurent and Bergé than Bonello, although neither director is sycophantic about either of their main characters. Both films portray Yves as shy, sensitive and immensely talented, charming to the women who surrounded him at work and at play. They also show him as a perpetual adolescent, who petulantly, even perversely hurt the men and women in his life, thus supporting Yves’ own assessment that he “was not so nice.” Bergé is depicted as a protective and almost paternal lover, although Bonello pays more attention to the shrewd businessman who built the Yves Saint Laurent couture house both around the designs and the designer’s public image.

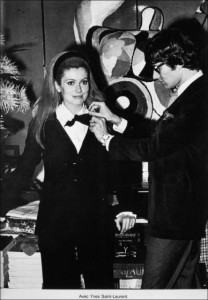

Both films pay as much attention to Yves Saint Laurent’s personal life as they do to his career and make a case that his personal problems, which included depression and mental breakdowns, were connected to his incredible creativity. He is often shown in poor health yet able somehow to pull himself together to draw sketches, select fabrics, add finishing touches to garments, and assemble remarkable and influential collections. Lespert’s movie covers a longer period, with a more positive approach: he tracks Saint Laurent’s career from his recognition by Dior in the early 1950s, to his loss of his position as chief designer for said house, to the establishment of his own label with the help of Bergé, culminating in his highly successful 1976 collection. Bonello focuses instead on the peak of Saint Laurent’s creativity between 1967 and 1976, which were also his drug and alcohol-addled years. He also devotes more attention to Yves’ affair with the debauched Karl Lagerfeld model/protégé, Jacques de Bascher (played by heartthrob Louis Garrel). Some of the excess may be new to viewers unfamiliar with recent, more scholarly biographies of Saint Laurent.[1]

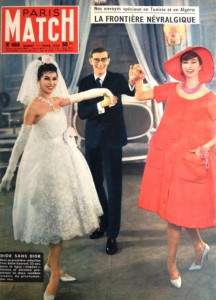

Fashion historians might wish to see both these films to get a better idea of his life and the transformation of his fashion shows from intimate to large, spectacular events. Scenes include behind-the-curtains last-minute prepping of the models, the catwalk, and the reactions of customers, buyers, and fashion journalists. Equally instructive are scenes where Yves inspects and makes alterations to the mock-up designs. However, viewers will find virtually nothing about the labor of cutting, sewing, and finishing carried out in the ateliers. For scenes of that essential aspect of the couture business, fashion historians must turn to the documentary Yves Saint Laurent, 5 avenue Marceau (2002), in which the designer was fully involved. The costumes in both films are exquisite and accurate, partly because many were originals, either loaned by the Yves Saint Laurent Foundation in Lespert’s film or by a private collector, Olivier Châtenet, in Bonello’s film. This meant that the actresses who modelled the clothes were cast to fit the clothing. Garments no longer available in pristine condition were reconstituted from photos and drawings with fabric samples (in the case of most of the colorful garments from the influential Ballets Russes collection of 1976) or by working from a worn version found in a flea market (in the case of the wedding dress shown on the cover of Paris Match in 1958).[2]

Film historians and critics will want to analyze both films for the directors’ style and techniques. Film buffs will want to compare the differences. Lespert takes a conventional bio-pic approach, proceeding more or less chronologically, using date titles to indicate the passage of time, usually, a matter of years. He rarely deviates from this narrative line, beyond flashing forward to Bergé preparing the couple’s extensive art collection for auction after Yves’ death in June 2008. His most extended flashback invokes a trope in many male couturiers’ autobiographies whereby a sensitive young boy draws on the skills of a dressmaking aunt or grandmother,[3] a trope that biographies of Saint Laurent (who drew but did not sew) reconfigure as that of a lonely boy closely attached to his fashionable mother, leafing through her fashion magazines, and drawing dresses.[4] Lespert in fact acknowledges his indebtedness to Lawrence Benaïm’s recently republished biography, Yves Saint Laurent.

Film historians and critics will want to analyze both films for the directors’ style and techniques. Film buffs will want to compare the differences. Lespert takes a conventional bio-pic approach, proceeding more or less chronologically, using date titles to indicate the passage of time, usually, a matter of years. He rarely deviates from this narrative line, beyond flashing forward to Bergé preparing the couple’s extensive art collection for auction after Yves’ death in June 2008. His most extended flashback invokes a trope in many male couturiers’ autobiographies whereby a sensitive young boy draws on the skills of a dressmaking aunt or grandmother,[3] a trope that biographies of Saint Laurent (who drew but did not sew) reconfigure as that of a lonely boy closely attached to his fashionable mother, leafing through her fashion magazines, and drawing dresses.[4] Lespert in fact acknowledges his indebtedness to Lawrence Benaïm’s recently republished biography, Yves Saint Laurent.

Lespert’s version by moments has a documentary feel, due in great part to the excellent acting. Pierre Niney, the youngest member of the Comédie Francaise, seems to incarnate Yves, to the point that I, and other viewers of both films, resisted the charms of the more conventionally attractive actor, Gaspard Ulliel, in Saint Laurent. Guillaume Gallienne, also of the Comédie Francaise, was equally convincing as Bergé in Yves Saint Laurent. Bergé is played by Jérémie Renier in the second version. Although actresses have lesser roles in both films, Charlotte Le Bon and Marie de Villepin, both models as well as actresses, play two of the muses, Victoire and Betty Catroux, and have more of a presence in Lespert’s movie.

Saint Laurent (2014) – Trailer English Subs by unifrance

Conversely, Saint Laurent is an arty, nonlinear film. Bonello makes allusions to Proust that add nuance about decadence for those who know their Proust. He foreshadows Yves’ decline, notably in an early scene of Yves lying unconscious on the ground, against a bleak cityscape. This initial depiction is disorienting, because it comes without explanation of when it happened or what took place. Once it is repeated in chronological order, we understand that it is part of Yves’ self-destructive lifestyle. In both films such a scene displays Bergé picking up the pieces after Yves engages in reckless behavior.

Bonello makes use of split screens, notably projecting the famous Liberation collection on one half of the screen and shots of the May ’68 demonstrations and university and factory occupations on the other half. The juxtaposition is meant to suggest that the collection was Saint Laurent’s response to, and reflection of, the insurrection. Certainly this was the take of the fashion house’s publicity and most contemporary fashion reporters faithfully repeated it. But, if the collection was a response to the times, was it necessarily a reflection of the insurrection? Might not the divided screen express a dissonance between Saint Laurent (and by extension, the whole couture business) and the insurgents? I was never convinced by the contemporary publicity about the collection. Having studied how couture houses in close collaboration with fashion magazines set about creating cults of designers, and unable to forget Saint Laurent’s lavish and dissolute life style depicted later in the same film, I prefer to interpret the divided screen as dissonance. Other students of fashion disagree and such disagreement can be productive. If used in a fashion history seminar, this split screen sequence, beefed up with some historical context, should prompt a lively discussion of what is involved in couture publicity.

Saint Laurent is more of an impressionistic portrait than a life story. By impressionistic I do not mean to imply that Bonello’s portrait is light and sunny, quite the opposite. The film is, however, composed of evocative scenes that stay in the viewer’s eye and mind. A striking example has Yves with a long-time customer who tries on one of his mannish jacket, shirt and pant outfits, not long after he introduced his gender-bending “smoking” jacket and tuxedo for women.The customer looks awkward and worries about looking masculine until Yves opens the top buttons of her shirt, lifts and artfully arranges her collar, and adds a necklace and bracelet. The customer/actress relaxes into the clothing and as she does, becomes more feminine and modern in appearance. The scene economically conveys the notion that style is much more than fashion and spotlights Saint Laurent’s dandy effect, his major innovation in women’s clothing of the late 1960s and 1970s.

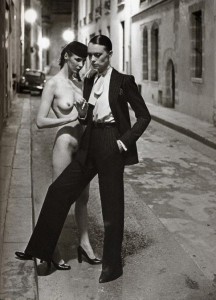

The gender issue is once more addressed in an amusing scene, albeit less persuasively. It depicts the shooting of the famous Helmut Newton (1920-2004) advertising photograph for Vogue in 1975, in which one model is naked save for hat and heels and another is mannishly coiffed and attired in a Saint Laurent suit posed in lamp-lit side street reminiscent of a B movie. The two models remark how cold they are and one asks the other what it is all about; the other replies that the photographer is playing with masculine codes. The audience, myself included, chuckled, as my undergraduate students had, a few years back, when I asked them to interpret the shot in a lecture on fashion photography. But I wonder whether models were as knowledgeable about gender analyses in 1975 as we are today.

The gender issue is once more addressed in an amusing scene, albeit less persuasively. It depicts the shooting of the famous Helmut Newton (1920-2004) advertising photograph for Vogue in 1975, in which one model is naked save for hat and heels and another is mannishly coiffed and attired in a Saint Laurent suit posed in lamp-lit side street reminiscent of a B movie. The two models remark how cold they are and one asks the other what it is all about; the other replies that the photographer is playing with masculine codes. The audience, myself included, chuckled, as my undergraduate students had, a few years back, when I asked them to interpret the shot in a lecture on fashion photography. But I wonder whether models were as knowledgeable about gender analyses in 1975 as we are today.

In the end, both films lack adequate historical and cultural contexts. Three examples will suffice. Although both films acknowledge Yves’ origins in Algeria and how the troubles over the Algerian War induced his breakdown and subsequent discharge from the army, they might have done more with decolonization and the colonial elements and especially the North African influences in his collections. Second, these films rightly note the role of Christian Dior in identifying and promoting the young Yves and also briefly mention stylistic similarities to Chanel’s dandy look. However, they fail to situate his style within the fashion trends of the 1960s and 1970s. Third, both films show how Yves was inspired to create his Mondrian dress from a book on Mondrian, but they leave out other cultural influences (such as the theatre) on his designs. Of course, the same might be said of most of publications on Saint Laurent or more precisely his style.[5] Anyone who has been influenced by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s work on the 1960s and 1970s fashion revolutions believes that individual creators are manifestations of the field of cultural production.[6] Of course, bio-pics are by definition about individuals and these two films cover long swathes of Saint Laurent’s life, making a more nuanced and contextualized approach difficult and perhaps impossible. Bonello’s version could easily be cut by half an hour or more, while still leaving little room for a more historically grounded approach. Whatever my reservations, the two movies succeed in covering the designer’s long career and mental states, each in its own way offering great viewing pleasure and many opportunities for interpretation, historical and otherwise.

In the end, both films lack adequate historical and cultural contexts. Three examples will suffice. Although both films acknowledge Yves’ origins in Algeria and how the troubles over the Algerian War induced his breakdown and subsequent discharge from the army, they might have done more with decolonization and the colonial elements and especially the North African influences in his collections. Second, these films rightly note the role of Christian Dior in identifying and promoting the young Yves and also briefly mention stylistic similarities to Chanel’s dandy look. However, they fail to situate his style within the fashion trends of the 1960s and 1970s. Third, both films show how Yves was inspired to create his Mondrian dress from a book on Mondrian, but they leave out other cultural influences (such as the theatre) on his designs. Of course, the same might be said of most of publications on Saint Laurent or more precisely his style.[5] Anyone who has been influenced by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s work on the 1960s and 1970s fashion revolutions believes that individual creators are manifestations of the field of cultural production.[6] Of course, bio-pics are by definition about individuals and these two films cover long swathes of Saint Laurent’s life, making a more nuanced and contextualized approach difficult and perhaps impossible. Bonello’s version could easily be cut by half an hour or more, while still leaving little room for a more historically grounded approach. Whatever my reservations, the two movies succeed in covering the designer’s long career and mental states, each in its own way offering great viewing pleasure and many opportunities for interpretation, historical and otherwise.

Jalil Lespert, Director, Yves Saint Laurent, 2014, Color, 106 min, France, Belgium, Wy Productions, SND, Cinéfrance 1888, Hérodiade, Umedia.

Bertrand Bonello, Director, Saint-Laurent, 2014, Color, 150 min, France, Belgium, Mandarin Films, EuropaCorp, Orange Studio, Arte France Cinema, Scope Pictures.

- Alicia Drake, The Beautiful Fall: Fashion, Genius and Glorious Excess in 1970s Paris (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2007) covers the combination of drug, drink, sexual excess and fashion innovation in the 1970s, paying as much attention to Lagerfeld and his coterie as she gives to Saint Laurent and his coterie.

- Hannah Marriot, `Yves Saint Laurent movie: a costume designer`s biggest challenge,` The Guardian, 18 March 2014, and “Anaïs Romand on designing costumes for ‘Saint Laurent, Style, ’May 16, 2014.

- Christopher Breward, “Couture as Queer Auto/biography,” in A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk (New Haven: Yale U.P. in cooperation with the Fashion Institute of Technology, 2013) p, 118 and 121, identifies both the trend to couturiers writing autobiographies and the trope in many of their autobiographies.

- Laurence Benaïm, Yves Saint Laurent, new ed. (Paris: Grasset, 2002).

- A partial exception would be Yves Saint Laurent Style (New York: Abrams, 2008), especially the contributions of a fine fashion historian, Florence Müller.

- Pierre Bourdieu and Yvette Delsaut, “Le Couturier et sa griffe: Contribution à un théorie de la magie,” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociale; I (Jan. 1975), and “Haute Couture and Haute Culture,” in Sociology in Question (London: Sage, 1993).