Michael Sibalis

Wilfrid Laurier University

Speaking on the hundredth anniversary of Victor Hugo’s death, Robert Badinter, Minister of Justice, told the French Senate in 1985: “Yesterday, several academic friends, like me great admirers of the poet, and I wondered what symbolic gesture would best honour the poet. We decided to head toward Les Halles to lay some flowers for both Victor Hugo and Gavroche, at the spot where the poet situated the latter’s death at the barricades, to show that this fictional hero, who emerged from the poet’s imagination, has come to incarnate our history and national character perhaps more fully than many real heroes.”[1] Such is the power of Les Misérables.

Since Hugo first published his novel in 1862, there have been more than three hundred French editions (according to the Bibliothèque Nationale catalogue), as well as translations into every major language (at least seven in English alone). Moreover, in whole or in part, Les Misérables has been adapted for the movie screen about sixty times since 1897.[2]

Since Hugo first published his novel in 1862, there have been more than three hundred French editions (according to the Bibliothèque Nationale catalogue), as well as translations into every major language (at least seven in English alone). Moreover, in whole or in part, Les Misérables has been adapted for the movie screen about sixty times since 1897.[2]

In my opinion, the best film version is the 1934 French one (directed by Raymond Bernard), which is available on DVD in the Criterion Collection. At 280 minutes, it offers a relatively complete retelling of Hugo’s novel. But any movie, even the longest, has to condense the massive and rambling novel, which forces directors to make difficult choices as to what to cut. Because moviegoers prefer a happy ending, most films end with Javert’s suicide, which sets Jean Valjean free from ruthless pursuit; most directors have preferred to ignore the hero’s retreat into solitude and his death at the very end of the novel. Other decisions are more dubious and significantly alter Hugo’s tale. For instance, the American 1952 version (directed by Lewis Milestone) entirely eliminates the Thenardiers, while the 1998 version (directed by Bille August) gives Cosette, probably Hugo’s most bland and passive female character, a ludicrous proto-feminist moment when she rescues Marius from Javert’s clutches by turning a gun on the policeman!

The most recent movie version (directed by Tom Hooper) avoids such obvious missteps and manages to convey the broad sweep of Hugo’s story line. It is, of course, the onscreen version of the smash musical by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, first staged in France in 1980, but which became a worldwide phenomenon only after the English-language production premiered in London (1985) and New York (1987). The musical boasts stage productions in 21 languages and 43 countries, with more than 60 million tickets sold. The movie is not an exact recreation of the theatrical experience, however. Cameron Mackintosh, who brought the musical to the British stage and has now produced the film, has explained that “I never wanted the film to just record the show, we wanted to reinvent it. It had to be taken apart …. When you’re watching the film, you’re not aware of how much it’s been altered. It’s much grittier than the original stage version, much more faithful, actually, to Victor Hugo’s original vision.”[3] In truth, the many fans of the original cannot fail but notice this difference (sex, crime and poverty inevitably appear harsher up on screen than across the footlights), as well as others: a number of the songs have been considerably shortened and one new one added, episodes from the book originally left out have been inserted to better tie the story’s episodes together, and there is overall a heightened emphasis on the theme of Christian redemption.

The most recent movie version (directed by Tom Hooper) avoids such obvious missteps and manages to convey the broad sweep of Hugo’s story line. It is, of course, the onscreen version of the smash musical by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, first staged in France in 1980, but which became a worldwide phenomenon only after the English-language production premiered in London (1985) and New York (1987). The musical boasts stage productions in 21 languages and 43 countries, with more than 60 million tickets sold. The movie is not an exact recreation of the theatrical experience, however. Cameron Mackintosh, who brought the musical to the British stage and has now produced the film, has explained that “I never wanted the film to just record the show, we wanted to reinvent it. It had to be taken apart …. When you’re watching the film, you’re not aware of how much it’s been altered. It’s much grittier than the original stage version, much more faithful, actually, to Victor Hugo’s original vision.”[3] In truth, the many fans of the original cannot fail but notice this difference (sex, crime and poverty inevitably appear harsher up on screen than across the footlights), as well as others: a number of the songs have been considerably shortened and one new one added, episodes from the book originally left out have been inserted to better tie the story’s episodes together, and there is overall a heightened emphasis on the theme of Christian redemption.

Movie critics are sharply divided over the merits and demerits of the movie, albeit in general agreement about the varied singing talents of the cast.[4] Historians – particularly teaching historians – will be more concerned with what the movie has to say about early nineteenth-century France and whether or not it can be of any use in the classroom. There are historical anachronisms, of course, usually minor (like a ten-franc paper note in 1823), but one that is especially flagrant: the display of the tricolour flag under the Bourbon Restoration (indeed, the movie’s opening shot is a bedraggled tricolour trailing in the sea).[5] The movie’s utterly miserabilist depiction of France is even more disconcerting. Apart from a tiny rich minority, the entire population appears poor, dirty and downtrodden, held in check only by the army and police. In such a situation, revolutionary upheaval requires no other explanation (and the film offers none). Violent revolt, as a response to poverty and repression, just seems inevitable. Hugo’s original text is never that simplistic. Offering a broad panorama of French politics and society, the novel certainly can be used as a point of entry into France in the 1830s and 1840s, as Robert Schwartz demonstrated some ten years ago at Mount Holyoke College with History 255,“‘Les Mis’ and ‘Les Media’: Realities and Representations in France of Les Misérables.”[6]

Nevertheless, if the movie captures the imagination of our students (and nothing is less certain; saccharine romance and Broadway tunes likely have limited appeal to today’s twenty-year-olds), it, too, can become an opportunity to educate. The message board of Internet Movie Data Base (IMDb.com) provided a telling example, when one moviegoer posted a particularly obtuse comment: “Fantine is a prostitute but I don’t see why we should suddenly feel sorry for her. She chose to become one. …She’s the one who needs to take responsibility for the use of her body in this unhealthy way.” That observation elicited a flurry of angry responses, including this: “The people who make these anti-Fantine comments need a quick history lesson. …Victor Hugo is fiction but it’s not science fiction set in a world he created, his setting is very real.” It is precisely this setting that can become the subject of classroom discussion and even for student research projects. What were economic conditions under the July Monarchy? How did ordinary people live and work? Who were the criminals? How fair was royal justice? The movie itself may answer none of these questions, except in the most simplistic and caricatural way, but students can be induced to go beyond the shortcomings of cinematic history to develop a better picture of the past.

The movie does a credible job of bringing alive early nineteenth-century Paris, even if the sets look somewhat artificial. The Paris that Hugo wrote about in 1862 was in the process of vanishing before Haussmann’s wrecking crews. In creating the backdrop to his novel, Hugo, living in exile, combined research, memory and imagination.[7] He described Paris as dark, crumbling and dirty, and this was intentional, for, as Claudette Combes has observed:

“The Paris of Les Misérables is a city of gloomy streets because of Jean Valjean’s decisions as a hunted man: he seeks out the neighbourhoods, streets, houses that will best hide him, that will plunge him into the anonymity of the big city. The real reason, however, is that Victor Hugo wants to write a History of the People and he places this History in its real environment: the paving stones and gutters of the streets, the old hovels, the faubourgs.”[8]

The movie does convey a strong sense of Hugo’s city. Apart from monuments like Notre Dame, Marius’s grandfather’s mansion, and an unconvincing Place de la Bastille (filmed somewhere in Britain), it shows nothing but narrow, twisting streets and drab, dark lodgings.

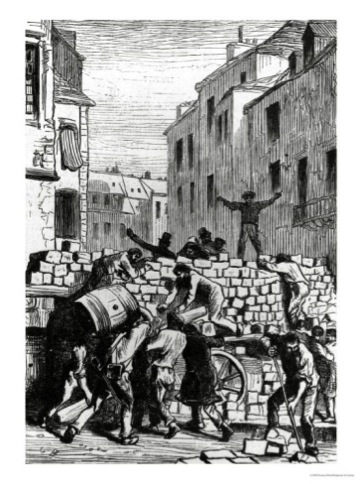

The historical highpoint of the movie is, of course, the failed insurrection of 5-6 June 1832. This was a relatively minor affair in the history of the July Monarchy, although it cost some three hundred lives: about 150 insurrectionists perished in the fighting and at least 131 police and soldiers. The uprising broke out more or less spontaneously, when clashes erupted between the troops and the republican crowd during General Lamarque’s funeral procession. Republican activists raised a number of barricades in the heart of Paris, but the popular uprising that they expected never materialized. The forces of order quickly put down the troubles and the last barricades fell on the morning of the 6th.[9] Charles Walton has recently criticized the film’s representation of the insurrection. “Why does the movie-musical present revolution as pointlessly Utopian rather than as a venerable, if tragic, vehicle of change, as Hugo saw it?” he asks. The answer, he suggests, is “our own pessimistic view of revolution.”[10] This is an astute observation, but it is also worth pointing out that in the 1830s most people, even on the Left, regarded June 1832 as a wasteful and pointless spilling of blood that did nothing to advance change.[11] Marius’s plaintive line – “Oh my friends, my friends, don’t ask me, what your sacrifice was for” – is therefore not in the least anachronistic. Opponents of the regime did try to glorify the uprising as a heroic defiance of tyranny when the surviving defenders of the famous Saint-Merry barricade were tried and convicted in October 1832, but June 1832 was soon eclipsed by later, bigger uprisings (like April 1834, February 1848 and June 1848) and almost forgotten.

Hugo changed all this when he put the failed insurrection at the heart of his story: “Les Misérables enabled [the 5th and 6th of June 1832] to cross the ages, [and] still today to inspire reflection and imagination.”[12] As Maitron’s dictionary of the labour movement notes, “it is difficult to imagine certain events in the revolutionary history of the July Monarchy other than the way Victor Hugo described them.”[13] To be sure, Hugo’s novel is actually rather muddled when disserting on the causes of these Parisian upheavals: “Outraged convictions, embittered enthusiasms, hot indignation, …gallant exaltation, blind warmth of heart, curiosity, a taste for change, …vague dislikes, rancours, frustrations, …discomforts, idle dreams, ambition hedged with obstacles…”[14] There is nothing in this litany about economic exploitation, political rights or social justice! Even so, Hugo portrayed June 1832 as something positive, and defined it as an “insurrection” (insurrection) rather than a “riot” (émeute): “[riot] is born of material circumstances; but insurrection is always a moral phenomenon.” Insurrection, then, was a fight for justice rather than for mere economic interests; it was a struggle on behalf of the whole nation against a small ruling faction, and it looked toward a better future.[15]

The film follows Hugo in giving a moral dimension to the June uprising – heroic sacrifice in a noble cause – but above all it implies that revolution in nineteenth-century Paris arose out of crime and poverty. This, of course, was Louis Chevalier’s thesis, refuted by a generation of research spearheaded by historians like George Rudé and Charles Tilly.[16] Such an interpretation ignores who actually did the fighting – mainly workers in the skilled trades – and pays little attention to ideology. The students – indeed, the film never makes it clear that they are students; moviegoers, unconversant with French history, probably see them as young bourgeois or, in Marius’s case, aristocrats who have a vague sympathy for social underdogs – give no real explanation for their struggle. They wave both the red flag (its significance unexplained) and the tricolour, and their battle cry is a meaningless “Vive la France!” instead of “Vive la République.”

But the real insurrection of 1832 occurred in a very specific ideological context. Disappointed with the establishment of the “bourgeois monarchy” in July 1830, a radical republican movement emerged that was committed to the seizure of power through violent insurrection and advocated the emancipation of the labouring classes. Leo Loubère labels this movement “Jacobin Socialism” and Jill Harsin calls it “montagnardism” or “montagnard extremism.”[17] As Harsin notes, by late 1832 radical republicanism was taking over from moderate republicanism on the Left, “its debut to be marked by the insurrection of 5-6 June 1832 …brought vividly to life by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables.”[18] As the film shows, radical middle-class youths – primarily students in law, medicine and engineering (at the École Polytechnique) – often took a leading role in the republican conspiratorial societies of the day, but (something the film doesn’t show) the masculinity and the pride of the skilled worker, whose social and economic position was being threatened by change, were at the heart of this movement. In his novel, Hugo explains in some detail the “faint revolutionary stir” of the early 1830s, embodied by Les Amis de l’A.B.C. (pronounced abaissé, i.e. “suppressed”) most of whose members were “students having friendly relations with a number of workers.”[19] This society is the fictional counterpart of the historical Société des Amis du Peuple and its successor, the Société des Droits de l’Homme which were behind much of the republican agitation in the early 1830s.

But the real insurrection of 1832 occurred in a very specific ideological context. Disappointed with the establishment of the “bourgeois monarchy” in July 1830, a radical republican movement emerged that was committed to the seizure of power through violent insurrection and advocated the emancipation of the labouring classes. Leo Loubère labels this movement “Jacobin Socialism” and Jill Harsin calls it “montagnardism” or “montagnard extremism.”[17] As Harsin notes, by late 1832 radical republicanism was taking over from moderate republicanism on the Left, “its debut to be marked by the insurrection of 5-6 June 1832 …brought vividly to life by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables.”[18] As the film shows, radical middle-class youths – primarily students in law, medicine and engineering (at the École Polytechnique) – often took a leading role in the republican conspiratorial societies of the day, but (something the film doesn’t show) the masculinity and the pride of the skilled worker, whose social and economic position was being threatened by change, were at the heart of this movement. In his novel, Hugo explains in some detail the “faint revolutionary stir” of the early 1830s, embodied by Les Amis de l’A.B.C. (pronounced abaissé, i.e. “suppressed”) most of whose members were “students having friendly relations with a number of workers.”[19] This society is the fictional counterpart of the historical Société des Amis du Peuple and its successor, the Société des Droits de l’Homme which were behind much of the republican agitation in the early 1830s.

Hugo’s barricade also reflects history. Hugo placed it on the Rue de la Chanverrerie (which he spelled Chanvrerie), described as one of “those dark, twisting, alleys running between tenements eight storeys high.”[20] This street, wedged between the Rue Mondétour and the Rue Saint-Denis, disappeared with the construction of the Rue Rambuteau in the late 1830s.[21] Although no barricade rose there in 1832, Hugo did draw on events at the Saint-Merry barricade and its lead defender Charles Jeanne (Hugo even mentions Jeanne and his barricade several times in the novel). This barricade blocked the intersection of the Rue Aubry-le-Boucher, the Rue Neuve Saint-Merry and the Rue Saint-Martin. The rebels set up their headquarters in a tavern at 30 Rue Saint-Martin, which is today roughly the site of the Café Beaubourg’s touristy terrace. Hugo also incorporated incidents from other Parisian insurrections, including 1848, but there are clear parallels between his fictional barricade and the Saint-Merry barricade. Among other things, like Javert, Inspector Vidocq in disguise infiltrated the barricade’s defenders in order to assess their strength, and a fourteen-year-old found among the dead likely inspired Hugo’s creation of the street-urchin Gavroche.[22] But in making students rather than workers the defenders of his barricade, Hugo – and the movie – distort history. Two-thirds of the insurgents in June 1832 were workers, the other one-third shopkeepers and clerks.[23] Although a few students – la jeunesse des écoles – apparently did engage in the fighting, they were by far the exception.[24] More specifically, the fourteen dead recovered at the Saint-Merry barricade, like those in Les Misérables, were almost all unmarried men in their twenties or early thirties, with a young boy of fourteen and an “old man” of sixty-three. But, apart from an élève en pharmacie, they were not at all the students portrayed in the novel or the film, but skilled craftsmen (tailor, cabinetmaker, house painter, bootmaker, baker …).[25]

If we ignore this gross misrepresentation of who actually did the fighting and dying, the movie’s depiction of the construction, defense and taking of a barricade is realistic – and almost a lesson in nineteenth-century street combat. (The gigantic and improbable barricade in the Place de la Bastille, seen in the movie trailer, appears only in the film’s coda, when the entire cast of characters, both dead and alive, reappear to belt out “Do You Hear the People Sing?”.) Costumes, sets and certain action scenes in this version of Les Misérables succeed in bringing aspects of the French past alive, but when dealing with complex social and political conditions, the movie resorts to cinematic oversimplification and caricature and therefore falls short. Even so, the film is dramatic, moving and immensely entertaining. As for students, they can probably get something of value out of it, but only if they are encouraged to look beyond what is shown on screen.

If we ignore this gross misrepresentation of who actually did the fighting and dying, the movie’s depiction of the construction, defense and taking of a barricade is realistic – and almost a lesson in nineteenth-century street combat. (The gigantic and improbable barricade in the Place de la Bastille, seen in the movie trailer, appears only in the film’s coda, when the entire cast of characters, both dead and alive, reappear to belt out “Do You Hear the People Sing?”.) Costumes, sets and certain action scenes in this version of Les Misérables succeed in bringing aspects of the French past alive, but when dealing with complex social and political conditions, the movie resorts to cinematic oversimplification and caricature and therefore falls short. Even so, the film is dramatic, moving and immensely entertaining. As for students, they can probably get something of value out of it, but only if they are encouraged to look beyond what is shown on screen.

Tom Hooper, Director, Les Misérables (2012), Color, 158 min, UK, Working Title Films, Cameron Mackintosh Ltd.

- Journal officiel de la République française: Débats parlementaires: Sénat, Année 1985 #20 (23 May 1985), Séance du 22 mai, 626.

- See “Adaptations of Les Misérables,” Wikipedia. And also the beautifully illustrated catalog of the exhibition at the Musée Carnavalet, 10 October 2008-1 February 2009): Danielle Chadych and Charlotte Lacour-Veyranne, Paris au temps des Misérables de Victor Hugo (Paris: Paris-Musées, 2008).

- Richard Ouzonian, “The Big Interview: Cameron Mackintosh,” Toronto Star, 15 December 2012, E3.

- See http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/les_miserables_2012/

- In case anyone needs reminding, the restored Bourbons banned the tricolour in 1814, which became France’s official flag again only in 1830.

- See www.mtholyoke.edu/courses/rschwart/hist255-s01/index.html

- Claudette Combes, Paris dans les Misérables (Nantes : CID éditons, 1981) and Émile Tersen, “Le Paris des Misérables,” Europe, Revue Mensuelle 394-395 (February-March 1962):92-109.

- Combes, Paris dans Les Misérables, 69.

- Thomas Bouchet, Le roi des barricades: Une histoire des 5 et 6 juin 1832 (Paris: Seli Arslan, 2000); Jill Harsin, Barricades: The War in the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, 1830-1848 (Palgrave Macmillan: NY and Houndmills, 2002), 57-64; Mark Traugott, The Insurgent Barricade (University of California Press: Berkeley, LA, London, 2010), 1-7, 267-68.

- Charles Walton, “The Missing Half of Les Mis: The Film’s Pessimistic View of Revolution – and Ours,” Foreign Affairs, 2 January 2013, online (www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/138737/charles-walton/the-missing-half-of-les-mis).

- Bouchet, Le roi des barricades, 65.

- Bouchet, Le roi des barricades, 156.

- “Hugo,” in Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier français, ed. J. Maitron, 3 vols. (Paris: Éditions ouvrières, 1964), 2:357.

- V. Hugo, Les Misérables, trans. Norman Denny, 2 vols. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980), 2:187.

- Hugo, Les Misérables, 2:187-207 (quotation 193). This translation renders émeute as “revolt” rather than “riot.” See also Bouchet, Le roi des barricades, 164.

- Louis Chevalier, Classes laborieuses et classes dangereuses à Paris pendant la première moitié du XIXe siècle (Paris: Plon, 1958), translated as Labouring Classes and Dangerous Classes in Paris during the First Half of the Nineteenth Century (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973). See Barrie M. Ratcliffe, “Classes laborieuses et classes dangereuses à Paris pendant la première moitié du XIXe siècle? The Chevalier Thesis Reexamined,” French Historical Studies 17, No. 2 (Fall 1991): 542-74.

- L. Loubère, “The Intellectual Origins of French Jacobin Socialism,” International Review of Social History 4 (1959): 415-31; Harsin, Barricades, 6.

- Harsin, Barricades, 57.

- Hugo, Les Misérables, 1:555-56.

- Hugo, Les Misérables, 2:219.

- See the map at http://www.chanvrerie.net/paris/1849fragment.html

- Thomas Bouchet, À Cinq heures nous serons tous morts! Sur la barricade Saint-Merry, 5-6 juin 1832: Charles Jeanne (Paris: Vendémiaire, 2011). On pp. 152-162, Bouchet analyses Hugo’s use of this barricade. See also Bouchet, “La barricade des Misérables,” in La Barricade, ed. Alain Corbin and Jean-Marie Mayeur (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1997), 125-35; and the discussion in Combes, Paris dans les Misérables, 157-77. For Vidocq, Bouchet, Le roi des barricades, 28.

- Harsin, Barricades, 60.

- Jean-Claude Caron, “Aux origins du mythe: l’étudiant sur la barricade dans la France romantique (1827-1851),” in La Barricade, 185-96; the insurrection of 1832 is discussed on 191-92. He concludes, however (195): “The barricade does not involve the middle class, but masons, carpenters, unskilled laborers, even if middle-class youths in uniform or civilian dress play a directing role. The Hugolian representation of the barricade of June 1832 has at least the merit of ideological clarity: the student sympathizes there with the child [Gavroche], himself a symbol of that generous but unthinking people who must be guided, educated, controlled.”

- Bouchet, À Cinq heures nous serons tous morts!,104-05.

I’m a lay person, not a historian. I found this a super lucid presentation of complex background issues about the 1832 uprising and a helpful discussion of the way both Hugo’s novel and the movie engage with those issues. Thanks!