Ethan Katz

University of Cincinnati

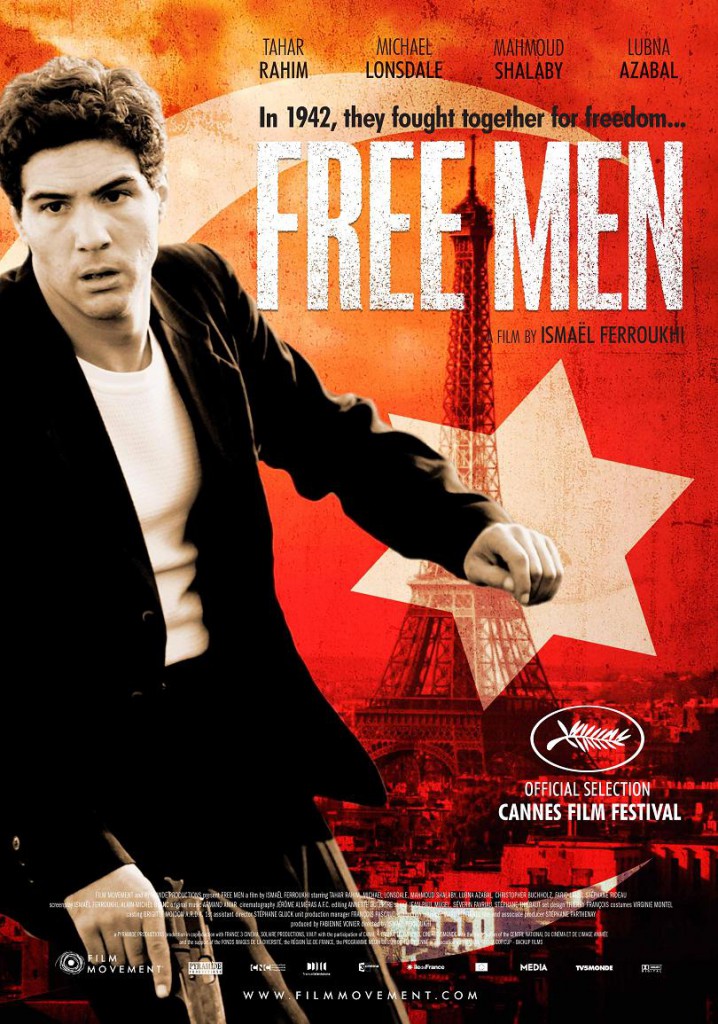

Amidst the torrent of attention given in recent years to the history of France during World War II, the place of Muslims under Vichy and the Occupation has remained relatively neglected. Yet tens of thousands of North African Muslim laborers resided in wartime France, and faced challenges – from ethics to allegiance, to politics, to subsistence – that at once echoed and diverged from those of the rest of the French population.[1] For these reasons alone, Moroccan-born French director Ismaël Ferroukhi’s 2011 film Les Hommes libres will be of substantial interest to teachers and students of French history and culture. The film paints a fascinating portrait of life in Occupied Paris, incorporating North African laborers and their music, culture, religion, and politics into the period’s cinematic landscape. At the same time, through its timely subject matter and its at once serious and selective use of historical research, it raises questions about the relationship between history and memory. Thus the film, if carefully framed, has the potential to stimulate productive scholarly and classroom discussion.

Les Hommes libres, based in part on actual historical figures and events, centers around Younes, a fictionalized Algerian laborer in Occupied Paris (the director describes him as a composite character from real historical actors). Younes, played by the rising star Tahar Rahim, begins the film as an apolitical black marketeer, trafficking in goods like cigarettes and coffee. Soon caught and apprehended for his illegal activities by French police, in exchange for his freedom Younes agrees to become an informant at the Grande Mosquée de Paris; he is instructed to report on all visitors to the rector of the mosque, Si Kaddour Benghabrit. Within the walls of the mosque, Younes and the film’s viewers are introduced to two actual historical figures who will assume central importance in the film. These are Benghabrit, and Salim Hallali, an Algerian-born Jewish singer whom the rector has chosen to protect (Hallali performs regularly in the mosque’s courtyard and at an adjacent café). Here we also encounter other important characters: Younes’ old friend Ali, who has been urging him to join the Resistance as a universal fight for freedom (“today in France, tomorrow in Algeria”); Leïla, an Algerian woman who works in the mosque and whom we later learn is a major communist résistante; and Major Von Ratibor, a German officer who comes regularly to the mosque and seems to have an affable rapport with Benghabrit.

Les Hommes libres, based in part on actual historical figures and events, centers around Younes, a fictionalized Algerian laborer in Occupied Paris (the director describes him as a composite character from real historical actors). Younes, played by the rising star Tahar Rahim, begins the film as an apolitical black marketeer, trafficking in goods like cigarettes and coffee. Soon caught and apprehended for his illegal activities by French police, in exchange for his freedom Younes agrees to become an informant at the Grande Mosquée de Paris; he is instructed to report on all visitors to the rector of the mosque, Si Kaddour Benghabrit. Within the walls of the mosque, Younes and the film’s viewers are introduced to two actual historical figures who will assume central importance in the film. These are Benghabrit, and Salim Hallali, an Algerian-born Jewish singer whom the rector has chosen to protect (Hallali performs regularly in the mosque’s courtyard and at an adjacent café). Here we also encounter other important characters: Younes’ old friend Ali, who has been urging him to join the Resistance as a universal fight for freedom (“today in France, tomorrow in Algeria”); Leïla, an Algerian woman who works in the mosque and whom we later learn is a major communist résistante; and Major Von Ratibor, a German officer who comes regularly to the mosque and seems to have an affable rapport with Benghabrit.

Even while Younes quickly becomes suspicious of certain individuals and activities in the mosque, he also strikes up a close friendship with Salim Hallali (there are even occasional hints of emotional involvement), and grows intrigued by the cause and activities of the Resistance. Thus the film’s hero grows increasingly reluctant to pass real information to the French police. In time he chooses to join the Resistance. On one of his first missions, he arrives a few hours too late to help the Jewish family to whom he had to deliver false papers and finds their children hiding with a neighbor. Despite initial misgivings, he makes the split-second decision to take the children with him. He brings them to the mosque for shelter, where, against the objections of another mosque official, Benghabrit defends their presence, insisting that “these children are our children” and must be protected.

Slowly, the surveillance of the Germans and the French police tightens around the mosque, and officials become increasingly wary of the rector, suspecting that he is sheltering Jews (including Hallali). Ultimately, Benghabrit protects Hallali with both false papers and the inscription of his father’s name on a tomb in the Franco-Muslim cemetery of Bobigny. Meanwhile, Leïla is arrested in a roundup. Younes participates in a rescue mission at the Franco-Muslim hospital that culminates in a shootout, where Ali loses his life but Younes escapes with Sarah, the older of the two Jewish children. Not long after, camouflaged by worshipers at the mosque, Younes and other resisters usher Sarah and her brother Eli to safety on a boat awaiting them in the River Seine. After yet another violent confrontation that affirms Younes as a courageous resistance fighter, the film concludes with short scenes from the period of the Liberation, linking explicitly the struggles against fascism and colonialism.

Both as cinema and historical portrayal, there is much for viewers to appreciate in this film. With its slow-moving plot this is hardly a wartime thriller, but it is beautifully shot; careful editing and special effects evoke the period effectively. Much of the action occurs in and around the mosque (because the Grande Mosquée de Paris did not grant permission to use the actual site, Ferroukhi filmed these segments in Morocco)[2] and nearby Arab cafés. They highlight the important and still-neglected reality of Muslims’ sizable presence in interwar and wartime Paris. The segments on Salim Hallali’s performances expertly capture the flavor of such settings. The actor (Mahmoud Shalabi) and the singer (Pinhas Cohen) defty recreate this forgotten Jewish founder of the Flamenco in Arabic — whose longtime collaboration with Muslim musicians embodied a bygone era of cultural cross-fertilization – for a new generation of viewers and listeners. Likewise, Tahar Rahim’s sensitive performance as Younes conveys the process of fear, indecision, and courage experienced by those who moved from relative indifference to active resistance. Michael Lonsdale’s convincing turn as Benghabrit offers insight into the balancing act that Philippe Burrin has termed “accommodation,” which often accompanied resistance, particularly for public figures monitored closely by the authorities.[3] In the classroom, each of these components could be highlighted for students. The film therefore communicates the larger atmosphere and challenges of the period, not only those particular to Muslims, but those experienced by the French population more broadly.

Yet certain of these same evocative portrayals — of Benghabrit mostly as a courageous, principled agent of resistance and protection; of the mosque as the heart of a small network of North African Muslim resisters; and of Algerian laborers as likely to see the anti-colonial and anti-fascist battles as one and the same – contain significant lapses. As we shall see, the selectivity here creates additional challenges but also opportunities for teaching the film. The director has clearly taken his cue mostly from an increasingly popular portrayal of Benghabrit and the mosque as emblems of heroic resistance. A magazine story on the subject was in fact, Ferroukhi has said, his initial inspiration for the film project. Indeed, several scenes are directly indebted to Derri Berkani, an Algerian-born French filmmaker, who depicted the role of the mosque in a 1991 documentary, and who is credited as consultant for Ferroukhi’s screenplay.[4] We can gauge Ferroukhi’s use of historical evidence from the scene where Major Von Ratibor reads to Benghabrit, word-for-word, the contents of an actual archival document that researchers (myself included) have cited, and that Berkani and others use to support their story. In the document, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs expresses its grave suspicion that the personnel (particularly the “imam”) of the Grande Mosquée are furnishing Jews with false certificates attesting that they are Muslim. Although the memo exists, the film implicitly dates it much later in the war (1942) than it actually appeared (September 1940),[5] and suggests misleadingly that the so-called imam in question was another official at the mosque, rather than Benghabrit himself.

Likewise, in the above-mentioned scene when Benghabrit declares “these children are our children,” he is quoting, nearly verbatim, a hand-written note in Kabyle that Berkani discovered in 2004. Dating from wartime Paris, it calls upon Muslim laborers to protect Jewish children, probably in the context of a major rafle. The trouble, however, as I have noted elsewhere, is that no archival record links this note to Benghabrit or the mosque.[6] More broadly, although there is evidence that the mosque saved a few Jews, no surviving records point to anything approaching the figure of roughly 1700 people advanced by Berkani and other leading advocates of the story. Ferroukhi’s film, what is more, completely overlooks Benghabrit’s cooperation with Vichy’s Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, as late as 1944, in confirming that several Mediterranean Jews who sought to pass as Muslim were not in fact Muslim.[7]

Ferroukhi is on surer ground with the story of Salim Hallali, one that the singer himself repeated many times, including the detail of the fabricated tomb in the Franco-Muslim cemetery (though there appears to be no historical basis for the scene where Hallali must show the tomb to the German officer to avoid arrest). He is also correct that the Franco-Muslim hospital, also under Benghabrit’s control, clearly sheltered wounded resisters and/or Allied soldiers. The issue of Algerian nationalists fighting fascism, however, is more of a mixed bag. The film is right in showing the refusal of nationalist leader Messali Hadj to collaborate with Vichy, and the 17 years of forced labor to which he was sentenced as a result. It is misleading, however, to suggest that most nationalists followed Messali’s lead and joined the Resistance. In fact, some leading figures in Messali’s organization, the Parti Populaire Algérien, reached out to the Germans and eventually did propaganda work for the occupiers. Their motivations were complex, born primarily from opposition to the French colonial presence in North Africa. Greater display of divergent Muslim positions would have demonstrated that, in reality, Muslims were no more immune to collaboration than any other sector of the French population.[8]

I have discussed these issues at greater length [accessible at this link]. Indeed, I humbly suggest that a combination of the film with the above-cited research can afford a rich opportunity for teaching. Utilizing Les hommes libres alongside a scholarly article covering much of the same material would enable students to compare and contrast the ways that filmmakers and historians approach historical situations. Moreover, some familiarity with French Muslims’ complex wartime history would make students appreciate better certain aspects of the film. For instance, Benghabrit’s frustration that the mosque has been “placed in danger” by Younes and his comrades underscores the Muslim leader’s wartime effort to safeguard his own position and that of his institution. Likewise, students might reflect on one of the film’s subplots: the double game played by one of Younes’ friends and his collaboration with the pro-German forces. The film’s very title invites discussion with its suggestion of not only a common struggle for freedom but also the basic liberty to choose for good or for evil under even the most challenging of conditions.

Les Hommes libres reminds us that films that provide great opportunities for teaching are not necessarily the most accurate. More fundamentally, at a time when Muslims’ place in France provokes public discussion, Ismaël Ferroukhi’s film is a powerful reminder of the historical complexities surrounding this issue and of its place in various strands of French collective memory.

- Historians have given various figures for France’s Muslim population at the fall of France in 1940, with estimates ranging from 50,000 to 100,000.

- Given that the Grande Mosquée de Paris was modeled quite consciously on Moroccan mosque designs, the chosen filming site is quite resminiscent of the actual one. Regarding the mosque’s design and its basis, see Naomi Davidson, Only Muslim: Embodying Islam in Twentieth-Century France (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012).

- See Philippe Burrin, France Under the Germans: Collaboration and Compromise, trans. Janet Lloyd (New York: New Press, 1996).

- Une Résistance oubliée…La mosquée de Paris de 40 à 44 (1991), film directed by Derri Berkani, 26 minutes, 1991.

- The chronological hints come from the fact that the first roundup of Jews (1942) occurs in the film shortly before the memo appears, as does the growing connection between the Resistance and certain Algerian nationalists, which took place substantially only after the August 1941 Atlantic Charter

- See Ethan Katz, “Did the Paris Mosque Save Jews? A Mystery and Its Memory,” Jewish Quarterly Review 102.2 (2012): 256-87. A French translation of the article is forthcoming in Diasporas: Histoire et Sociétés, December 2012

- Ibid. This issue had already been visited, before Ferroukhi began research for his film, in Jean Laloum, ‘‘Des Juifs d’Afrique du Nord au Pletzl? Une presence méconnue et des épreuves oubliées (1920–1945),’’ Archives Juives 38, No 2 (2005): 47-83.

- Regarding the sometimes-successful Nazi efforts to recruit Muslims in France and North Africa, see, among others, Charles-Robert Ageron, “Les populations du Maghreb face à la propagande allemande,” Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale 29, no. 114 (1979): 1-39; Raffael Scheck, “Nazi Propaganda Toward French Muslim Prisoners of War,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies, forthcoming.

Thanks for posting this excellent review, Ethan, and for sharing your expertise on the subject with us. I like the film I lot, but for the reasons you say I think it works better when shown alongside your JQR article (that’s what I did when we showed the film in San Diego)!

Pingback: Les Hommes libres | Foreign Language Arabic