Charlotte C. Wells

University of Northern Iowa

Edward Bulwer Lytton wrote the famously turgid sentence that begins “It was a dark and stormy night” in 1830, but Simon Mirren and David Wolstencroft, creators and “showrunners” of the television series Versailles, find that metaphoric storms also troubled the seventeenth century. It is indeed a night of rain and thunder as Episode One begins. Anne of Austria lies dying with her son, the king of France, as her sole attendant. Like many another dying visionary, she gives young Louis XIV, played by George Blagden, excellent advice for the future. “A king without a castle is not a king at all,” she tells him. “You dream of paradise. Now you must build it for yourself.” [1] So begins Mirren and Wolstencroft’s saga of the building of the great palace of Versailles. The scene is an appropriate introduction to the show and its puzzles. We have here Louis XIV as Gothic hero, startled awake in his royal bed to realize he’s received his mother’s counsel in a dream. The viewer is left to wonder why Anne? Why not Cardinal Mazarin, who was, after all, Louis’ real mentor in statecraft? But that’s Versailles for you. It offers lots of sex, lots of blood, and plenty of male and female cross-dressing, but not much in the way of historical accuracy.

This in spite of the fact that the creators have done their research—or rather they hired historian Matthieu da Vinha, Director of the Research Center of the Château of Versailles, to give them tips on etiquette. [2] Thus most of the events and people who appear on screen were real, but not at the time and not in the way the series suggests. While that is certainly acceptable in a work of fiction, the drama that results significantly distorts the events and personalities of the early years of the Sun King’s personal reign.

The first season claims to present events of 1667-1670. The story line focuses on noble resistance to the Inquiry into the Nobility that Louis began in 1666 to define and detect false nobles—and hence, to the power of the young Sun King himself. A fictional Huguenot villainess, Madame de Clermont, and an equally fictional duke, Cassel, appear to lead the plot to stop the construction of Versailles, although how this will halt the Inquiry never becomes clear. There are some detours from the main story line: Queen Maria Theresa gives birth to a black baby—portrayed as the child of a visiting Senegalese prince—at the end of the first episode. While the second episode shows the fate of the child and the king punishing his wife with brutal sex, it’s hard to see what this has to do with the theme of the series, other than a suggestion that the gold of Senegal will finance the construction of Versailles. Then there is the royal doctor, poisoned by Madame de Clermont for reasons unclear, and whose place is taken by his daughter, Claudine (Lizzie Boucheré). The king insists she dress as a man. There were no female doctors at the court of France, of course. The masquerade might seem reasonable given the overall nonsense—except that Doctor Claudine plays only a very minor role in the series, bandaging wounds (a task that would have been left to lowly surgeons) and announcing she cannot save the poisoned Maria Henrietta. Why bother to have her? [3]

The first season claims to present events of 1667-1670. The story line focuses on noble resistance to the Inquiry into the Nobility that Louis began in 1666 to define and detect false nobles—and hence, to the power of the young Sun King himself. A fictional Huguenot villainess, Madame de Clermont, and an equally fictional duke, Cassel, appear to lead the plot to stop the construction of Versailles, although how this will halt the Inquiry never becomes clear. There are some detours from the main story line: Queen Maria Theresa gives birth to a black baby—portrayed as the child of a visiting Senegalese prince—at the end of the first episode. While the second episode shows the fate of the child and the king punishing his wife with brutal sex, it’s hard to see what this has to do with the theme of the series, other than a suggestion that the gold of Senegal will finance the construction of Versailles. Then there is the royal doctor, poisoned by Madame de Clermont for reasons unclear, and whose place is taken by his daughter, Claudine (Lizzie Boucheré). The king insists she dress as a man. There were no female doctors at the court of France, of course. The masquerade might seem reasonable given the overall nonsense—except that Doctor Claudine plays only a very minor role in the series, bandaging wounds (a task that would have been left to lowly surgeons) and announcing she cannot save the poisoned Maria Henrietta. Why bother to have her? [3]

There may well have been resistance to the demand to document noble status. A bigger problem with Versailles is temporal compression. Its creators collected titillating events from two decades and dropped them all into a relatively brief interval. For example, the probably oxygen-deprived baby who gave rise to the story of a black daughter was born in 1661.

There is a war going on in the background, but which war? Presumably it is the War of Devolution, 1667-1668, but the historical Louis XIV took an active part in that clash. Here Louis broods in the palace, while his brother Philippe seeks glory on the battlefield. (The Battle of Cassel, Philippe’s greatest achievement as a military commander, took place in 1674, not during the War of Devolution.) And if the war is the War of Devolution, also temporally displaced is the often-expressed fear of William of Orange. William was in his late teens and struggling to claim his family’s traditional offices in the Netherlands during the time covered by the series. He did not become betrothed to his cousin Mary Stuart until 1677. Other instances abound; perhaps most blatant is the permanent presence of the entire court at Versailles. Louis did not move there permanently and completely until 1682. Only a few episodes fall into chronological line: the signing of the Treaty of Dover, followed by Henrietta Maria’s death, ends the first season in 1670, which is when the actual events occurred.

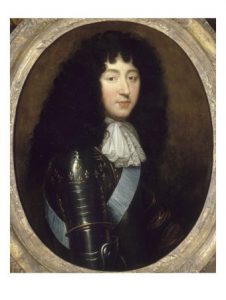

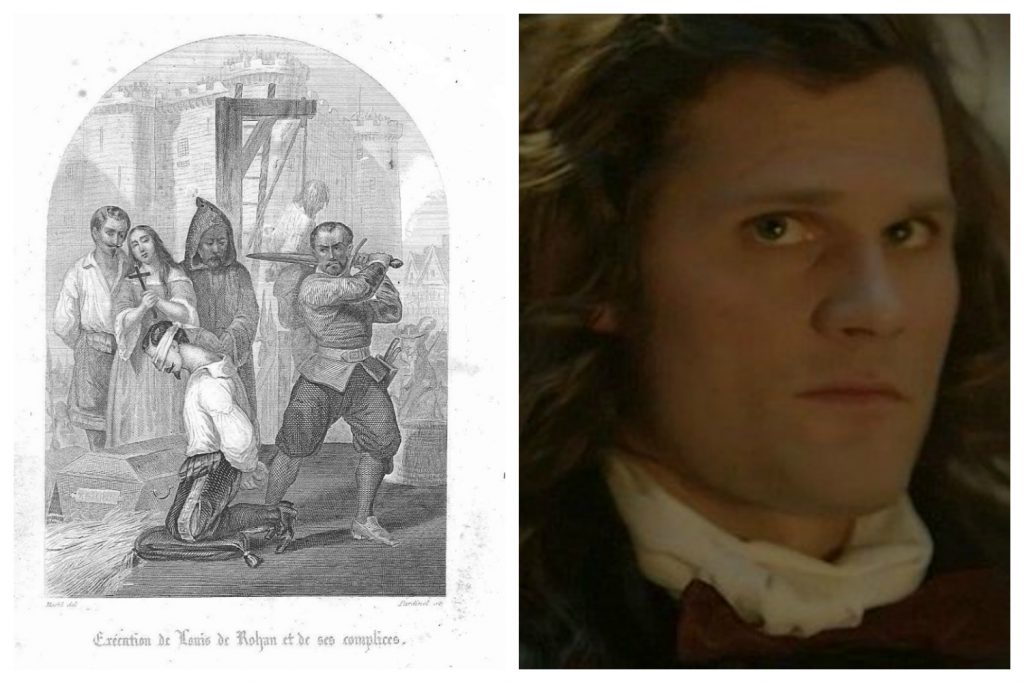

As the season progresses, the pro-nobility and anti-king conspiracy does come closer to reality as it echoes an actual plot, again not entirely in its chronological place—the Latréamont conspiracy. Gilles du Hamel de Latréamont made several attempts to raise a rebellion in Normandy in the 1660s. In its final form, the plot intended to turn Normandy into an independent state, murder the king, kidnap the Dauphin to use him as a figurehead—oh, and destroy Versailles. The Chevalier de Rohan, indeed the king’s childhood friend, but by then exiled from the court and burdened with debt, supported Lautréamont along with a few other discontented nobles. Alert Musketeers uncovered the conspiracy. Nothing came of it, and Rohan was executed in 1674. Here Rohan (played by Alexis Michalik) is the true mastermind of noble resistance, the serpent coiled at the heart of Versailles. The king’s intimate friend and a member of his inner circle, Rohan abuses that trust to kidnap the Dauphin in the season’s final episode [4]. How the Dauphin is to be rescued remains to be seen.

The impression left by all the hurly-burly is that the late 1660s were a very unsettling time indeed in the life of the Sun King. George Blagden plays Louis as someone who shows every sign of being overwrought. He shouts at his council and breaks furniture at moments of particular upset. He rides headlong and unattended through the forest of Versailles, at one point engaging in a stare-down with a pack of wolves.

The impression left by all the hurly-burly is that the late 1660s were a very unsettling time indeed in the life of the Sun King. George Blagden plays Louis as someone who shows every sign of being overwrought. He shouts at his council and breaks furniture at moments of particular upset. He rides headlong and unattended through the forest of Versailles, at one point engaging in a stare-down with a pack of wolves.

His relations with his brother seem to be his deepest emotional tie but they run from anger to studied indifference, with only the occasional dose of reluctant fraternity. For the rest, Blagden’s Louis wears a perpetual half-smile. He wears it when he informs his wife that he didn’t have her adulterous child killed after all, when watching Louise de la Vallière enter a convent (which did not actually happen until 1677) and when discussing life with his gardener, a one-handed veteran who of course offers better advice than all the royal councilors. He lapses into occasional snarls at his brother, though there, too, blandness generally prevails.

Alexander Vlahos’ Philippe is the most sympathetic character in the series, to some degree unhistorically so. The actual Philippe did indeed pursue a long-term relationship with the Chevalier de Lorraine, whose first name is never mentioned in the series—perhaps because he was also Philippe. But Philippe d’Orléans and his first wife perpetually quarrelled, and their household—never seen in the series—was divided between the Chevalier’s adherents and Madame’s in a cold war that often heated up.

Versailles’ Philippe joys in his love for the Chevalier, while still manifesting a wistful affection for his wife and jealousy over her affair with his brother (this never happened, although the king and the princess went through a flirtatious stage). Philippe shows a real gift for military affairs, unlike his brother, who is content to leave it to the generals, yet another distortion of historical reality. In this fantasy Versailles, Louis eventually sends Philippe into battle but frustrates him yet again by pulling him out from fear for his safety. Sibling rivalry reaches its peak in the last episode, when Louis and Philippe sit on either side of the dying Madame, quarreling over which of them is most responsible for her demise. In fact Rohan is most responsible, having suborned one of Henrietta Maria’s maids to poison her mistress. The distraction thus provided allows him to kidnap the Dauphin.

Versailles’ Philippe joys in his love for the Chevalier, while still manifesting a wistful affection for his wife and jealousy over her affair with his brother (this never happened, although the king and the princess went through a flirtatious stage). Philippe shows a real gift for military affairs, unlike his brother, who is content to leave it to the generals, yet another distortion of historical reality. In this fantasy Versailles, Louis eventually sends Philippe into battle but frustrates him yet again by pulling him out from fear for his safety. Sibling rivalry reaches its peak in the last episode, when Louis and Philippe sit on either side of the dying Madame, quarreling over which of them is most responsible for her demise. In fact Rohan is most responsible, having suborned one of Henrietta Maria’s maids to poison her mistress. The distraction thus provided allows him to kidnap the Dauphin.

Perhaps one of the greatest distortions of accepted history comes from the casting of Elisa Laskowski as Queen Maria Theresa. The historical queen was a fair-haired Hapsburg, plain, simple, and unwise enough to commit the social solecism of falling in love with her husband. Laskowski as queen is darkly gorgeous, aloof, and quite intelligent enough to carry out a truly remarkable revenge on her indifferent husband by betraying him with an African. An African prince, granted, but still an African. Highly implausible, since Maria Theresa was probably deeply imbued with the Spanish notion of limpieza de sangre. But in the series’ alternate reality, the viewer has to wonder how Louis, so devious himself, could possibly despise such an intricate mind in such a beautiful body.

The lesser characters do to some degree echo historical reality, though not all are historically real. The biggest surprise is Stuart Bowman as Alexandre Bontemps, First Valet to the king and Governor of Versailles. Bontemps makes it into few history books, but he was unquestionably real and seems to have really enjoyed the king’s trust, though it isn’t likely the Sun King ever invited him to pull up an armchair and sit down by the fire for a chat, as the fictional Louis does. Bontemps’ presence in the series can probably be explained by the fact that da Vinha has written a book about him [5]. Steve Cumyn as Colbert and Joe Sheridan as Louvois look like the characters they portray—though the real Louvois was 26 in 1667 and this version is distinctly middle-aged. But they have little to do. Versailles’ Louis spends scarcely any time at all in their company—much less devoted himself to managing his ministers as the real king did. Anna Brewster as Madame de Montespan conveys some of the real marquise’s iron determination to attract the king, though her beauty belongs to the twenty-first century, not the seventeenth. Tygh Runyan plays Fabien Marchal, the fictional character with the greatest verisimilitude. Marchal is the king’s “chief of security.” His efforts to hunt down the plotters and make the road to Versailles safe for travelers bring to mind the work of Nicholas de la Reynie, which began in Paris in 1667. They even look alike. But one doubts that the actual la Reynie took the time to torture suspects himself, as Marchal does all too often. La Reynie had a large staff, but Marchal operates alone, especially after he is forced to execute Madame de Clermont, with whom he has fallen in love.

Marchal and Clermont’s sex scenes are especially animalistic, but most of the characters seem to be caught up in rutting reason. Sometimes it seems intended to be cute, as when Philippe, interrupted in a session of oral sex with the Chevalier, remarks that it’s fine, because he couldn’t eat another bite. Sometimes it’s just puzzling. Why does the king seem to prefer his women on top? This seems unlikely, given his alpha male personality, as well as historically dubious. Can it be that the showrunners want to give their audience some historical titillation? Women are on display, fully and frequently. Men are not. Even when Philippe and the Chevalier are shown (literally) sleeping with each other, they are cuddled together with all their more personal parts neatly under the covers.

Marchal and Clermont’s sex scenes are especially animalistic, but most of the characters seem to be caught up in rutting reason. Sometimes it seems intended to be cute, as when Philippe, interrupted in a session of oral sex with the Chevalier, remarks that it’s fine, because he couldn’t eat another bite. Sometimes it’s just puzzling. Why does the king seem to prefer his women on top? This seems unlikely, given his alpha male personality, as well as historically dubious. Can it be that the showrunners want to give their audience some historical titillation? Women are on display, fully and frequently. Men are not. Even when Philippe and the Chevalier are shown (literally) sleeping with each other, they are cuddled together with all their more personal parts neatly under the covers.

The series is beautifully produced, with a variety of French chateaux standing in for Versailles-in-the-making; some of the filming is actually done in the palace itself. The costumes are sumptuous, and the lighting effectively sets a dark and brooding mood. There’s very little of the sun from which Louis took his symbol, and perhaps that’s one way to sum up the series. The characters are mired in metaphorical darkness. We see nothing of the actual work Louis XIV did to unify and uplift his country. We see nothing of the true problems of the seventeenth-century French monarchy. We don’t see much of the actual work and planning that went into the construction of Versailles. For that matter, we never really see why the king does not care to live in Paris—all he says is that he isn’t king of Paris, he’s king of France.

The series is beautifully produced, with a variety of French chateaux standing in for Versailles-in-the-making; some of the filming is actually done in the palace itself. The costumes are sumptuous, and the lighting effectively sets a dark and brooding mood. There’s very little of the sun from which Louis took his symbol, and perhaps that’s one way to sum up the series. The characters are mired in metaphorical darkness. We see nothing of the actual work Louis XIV did to unify and uplift his country. We see nothing of the true problems of the seventeenth-century French monarchy. We don’t see much of the actual work and planning that went into the construction of Versailles. For that matter, we never really see why the king does not care to live in Paris—all he says is that he isn’t king of Paris, he’s king of France.

It would be difficult to use Versailles in the classroom, at least for historical purposes. It might work as an example in a discussion of the evolution of the costume drama, and for the historical trivia buff, the game of figuring out what actually happened and what did not is fascinating. But the events are too compressed and the characters and relationships too distorted to allow any insight into the real achievements and failures of Louis XIV and his great palace. The BBC has renewed the series for two more seasons, and Season Two will be available in the US, again on Ovation, in fall 2017. Indications are that the darkness will grow darker, with the Sun King sunk in debauchery and his dream of light at risk [5].

This reviewer has somehow become the FFFH house expert on historical schlock, a duty normally full of entertainment, if not uplift. This time it was painful. On the official schlockometer, Versailles is the perfect 10. It doesn’t have the historical resonances of some of the Three Musketeers versions (2016); it doesn’t provide any mythic guidance for teenage girls (Reign, 2014). All it offers is beautiful and ruthless people fornicating and scheming and, frankly, the denizens of the real Versailles did those things a lot better. Avoid at all costs!

David Wolstencroft and Simon Mirren, Creators,Versailles, 2015, Series 1, 10 x 52 min, France, Canada, CAPA Drama, Zodiak Fiction and Documentaries, Incendo Versailles Productions Inc, Canal +.

NOTES

- Versailles, episode 1. First broadcast November 16, 2015 by Canal +. Written by David Wolstencroft and Simon Mirren and directed by Jalil Lespert.

- ABC Action News interview with George Blagden and Alexander Vlahos. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B7HpsoPFlzw

- The Latréamont conspiracy and Rohan’s part in it are laid in out in detail by Alfred Maury, “Une Conspiration républicaine sous Louis XIV – Le Complot du Chevalier de Rohan et de Latréamont,” Revue des Deux Mondes, 3e période, tome 6, 1886 (pp. 376-406). https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Une_Conspiration_r%C3%A9publicaine_sous_Louis_XIV_-_Le_Complot_du_Chevalier_de_Rohan_et_de_Latr%C3%A9amont/0. Accessed February 19, 2017.

- Mathieu da Vinha, Alexandre Bontemps, Premier valet de chambre de Louis XIV, éd.Perrin, “Les métiers de Versailles,” Paris, 2011.

- Nancy Tartiglione, “Versailles Season 2 Courted by BBC, Amazon UK,” Deadline Hollywood, Oct. 17, 2016. http://deadline.com/2016/10/versailles-bbc2-amazon-midnight-sun-global-sales-french-drama-trend-mipcom-1201837390/. Accessed February 20, 2017.