Denise Fisher

Australian National University Centre for European Studies*

May 1988. The French territory of New Caledonia had been in the grip of civil war, euphemestically known as ‘les evénéments,” for over seven years. For decades, many white Europeans and indigenous Kanaks alike had been seeking greater autonomy and even independence, the latter a goal of the largely Kanak-based coalition, the Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS). The French State itself had generated expectations of greater autonomy after World War II, when it created the French Community of overseas territories, but in New Caledonia, it had shown a pattern of granting elements of autonomy only to revoke them in successive statutes ever since – twelve in all, from 1958 to May 1988. Frustrations had mounted, and from 1982 had degenerated into violent protests to which the French responded by increasingly firm administration and control.

On the island of Ouvéa, as part of a broader protest, a pro-independence Kanak group decided to attack a police station at Fayoué, killing four policemen and taking four as hostages to a remote cave near Gossanah. They were seeking revocation of the latest statute, named after Minister for Overseas Departments and Territories, Bernard Pons, and wanted to annul imminent local territorial elections. Their timing proved to be disastrous: the incident – timed on the eve of the local vote which they wanted to abrogate – also occurred between the first and second rounds of the 1988 French presidential elections. The stakes for the French therefore sky-rocketed as then Prime Minister, conservative Jacques Chirac, competed with the left candidate François Mitterrand for the Presidency. Neither wanted to appear weak over the issue. What had started as an audacious local challenge to French authority, confronted the power of the French Republic at the highest level. The French Republic responded accordingly, sending in crack troops to rescue the hostages, resulting in 21 more deaths (19 Kanaks and 2 more French policemen). Both Chirac and Mitterrand had signed the orders to attack.

On the island of Ouvéa, as part of a broader protest, a pro-independence Kanak group decided to attack a police station at Fayoué, killing four policemen and taking four as hostages to a remote cave near Gossanah. They were seeking revocation of the latest statute, named after Minister for Overseas Departments and Territories, Bernard Pons, and wanted to annul imminent local territorial elections. Their timing proved to be disastrous: the incident – timed on the eve of the local vote which they wanted to abrogate – also occurred between the first and second rounds of the 1988 French presidential elections. The stakes for the French therefore sky-rocketed as then Prime Minister, conservative Jacques Chirac, competed with the left candidate François Mitterrand for the Presidency. Neither wanted to appear weak over the issue. What had started as an audacious local challenge to French authority, confronted the power of the French Republic at the highest level. The French Republic responded accordingly, sending in crack troops to rescue the hostages, resulting in 21 more deaths (19 Kanaks and 2 more French policemen). Both Chirac and Mitterrand had signed the orders to attack.

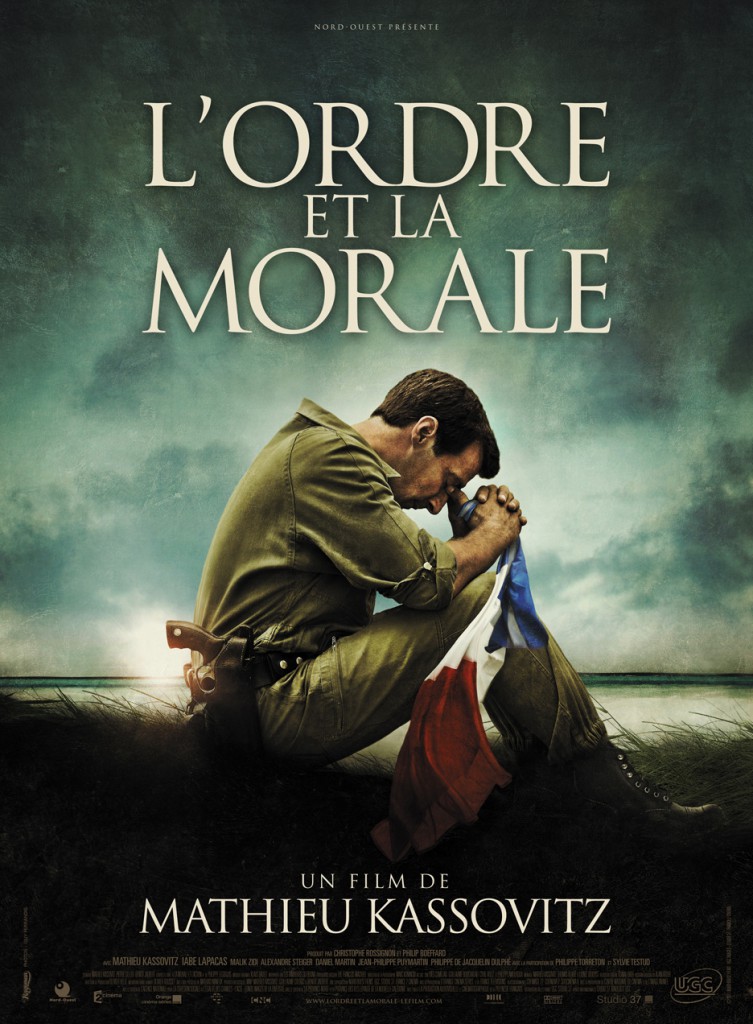

Mathieu Kassovitz’ film, L’ordre et la morale,or Rebellion in its English release, captures the strong sentiment, confusion, misunderstanding and political intensity of the May 1988 events. It rehearses the sequence of events through the eyes of Colonel Legorjus (played by Kassovitz), a mediator initially sent to negotiate, but whose role is presented as preempted by the political decision, taken during the height of the French presidential campaign, to mount an assault. Based on the autobiographical book by Legorjus,[1] it is a story of violence, military force and brutality, tactical errors, betrayal, and, “Order and Morality” (“L’ordre et la morale”) with all the irony and paradox the situation entailed.

The production was controversial, filmed in the neighbouring French territory of French Polynesia because, with the wounds of the incident still raw twenty four years later, the indigenous inhabitants of the New Caledonian island of Ouvéa refused to let him film there. Pro-French leaders reportedly tried to prevent filming in French Polynesia.[2] One Kanak involved in the Gossanah hostage-taking, later imprisoned by France, Benoît Tangopi, has written that the film is inaccurate and that Legorjus presented a biased version of his own role.Tangopi claimed Legorjus meant to deceive the Kanak hostage-takers, not to negotiate genuinely with them.[3] Four of the principal French figures depicted in the film (Minister Pons, General Vidal who headed the army during the assault, his offsider Colonel Benson, and the Deputy Public Prosecutor Jean Bianconi) have also formally protested the film’s depiction of their own roles. Another senior French figure, Michel Rocard, who led a peace mission shortly after the events depicted in the film, has confirmed that, sadly, the film was only too accurate.[4] It is not surprising that individuals on both sides disagree with Kassovitz’ version of events. For the film discredits both French officials and the FLNKS while highlighting Legorjus’s role. The question of whether this is simple poetic license in the interest of art, a deliberate misrepresentation of the truth, or simple inevitable subjectivity of the author-protagonist, will remain an issue surrounding the film. Perhaps, precisely because it seems to have displeased figures on both sides, the film may thereby reveal some essential truths, regardless of issues of objectivity.

The largest cinema owner in New Caledonia declined to show the film in New Caledonia, apparently under pressure from pro-French political forces probably concerned about sparking violence. In the event, the film was shown there by smaller operators, a month after its French release. It is a credit to the French State that the film was made on French soil at all, with the support of France 2, a public television station, and that the film was indeed shown in New Caledonia, to audiences that comprised Europeans and Kanaks alike. Cinemas were full, and the run had to be extended.[5] There was no violence, a testimony to how far the peoples of New Caledonia have come since the events the film portrays.

In agreeing to the making and release of the film, French authorities were perhaps acknowledging the significance of the events at its heart. For it was the failure of the heavy-handed assault on Kanak hostage-takers at Gossanah which resulted in Mitterrand’s dispatching a peace mission to New Caledonia after his re-election, a mission under Rocard which produced conciliation and paved the way for the June 1988 Matignon/Oudinot Accords. But feelings ran very deep. Less than a year later, the pro-independence leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou and his deputy were assassinated by a disaffected supporter. Nonetheless, the Matignon Accord agreements, later transformed and extended in the 1998 Nouméa Accords, produced the peace and tolerance, and economic prosperity, which have prevailed in New Caledonia since.

By releasing the film in New Caledonia, the French authorities have been mindful of the need to remember the lessons of the past. All sectors of society in New Caledonia – indigenous Kanaks (who make up over 40% of the population); the longstanding white community (about a third); and others, including newly-arrived Polynesians from the other French Pacific territories (about 10%) [6] — are being invited to remember. To remember that less than thirty years ago people on both sides (Kanak and white, pro-independence and pro-France) lost their lives over the future of New Caledonia. A reminder is crucial now, as the Nouméa Accord expires in 2018 and preparation for a long-promised independence vote, with all its attendant risks, is beginning.

Kassovitz’ film underlines what is at stake, portraying efforts by some passionate Kanaks to promote independence, pitting them against the might of the French State. His portrayal of the lead negotiator, who believed he had been hired to avert violence by winning the confidence of the ringleaders, is certainly sympathetic. We witness Legorjus’ increasing sense of betrayal and helplessness as he watches events overtaken by the charged election campaign back in mainland France.

Kassovitz sets the scene with skill, relating the increasing engagement of French forces as the hostage situation develops, and interweaving the parallel, and often opposing, interests of the police, for whom Legorjus works; the army; the politicians; and the local Kanak people, including ordinary villagers and elders, some employed for the French authorities, and the hostage takers who each have differing motivations, concerns and loyalties. Legorjus arrives prepared to do his duty as negotiator, only to see his role marginalized and even used to deceive the hostage-takers as French political decision-makers decide to mount an assault.

The French cracking of a nut with the proverbial sledgehammer is a recurrent theme, evident the moment Legorjus lands in Noumea, ready to negotiate. The airport is crawling with soldiers prompting his newly arrived police commander to observe “Shit, it’s a virtual invasion.” We learn that over 300 French crack troops have been deployed to deal with a handful of Kanak hostage-takers. The French war-council actually considers using a 250 kg laser-guided bomb, napalm and 20 mm cannons. The film depicts the often-senseless violence, culminating with the assault on the cave, pitting French Special Forces against untrained and poorly armed Kanaks. Finally, once the assault is accomplished, we see at least one Kanak prisoner summarily executed by French troops, and, as the film draws to a close, the suggestion that the ringleader, Dianou, was murdered.

Kassovitz uses symbolism expertly, contrasting the well-equipped and uniformed French troops with the bedraggled Kanaks in their shorts and t-shirts. Legorjus and his team fit somewhere in-between, initially wearing civilian clothes but donning uniforms for their military operation. While highlighting the underlying Kanak disposition to discuss and talk through problems, Kassovitz does not shy awa from the violence of the Kanak hostage-takers, which he depicts as born of desperation and a feeling of oppression.

Kassovitz displays a masterful command of the complex competing interests in New Caledonia, which persist to this day. The leader of the hostage-takers, Dianou, prescient in his early judgement that there would inevitably be a French assault (“that is how you solve your problems”), says that he could not go back. If he didn’t persist, all those who had died in the past (not just the four policemen killed in the hostage-taking, but all the victims of the recent civil war) would have died in vain. From his perspective, the bloodshed and French inflexibility could be explained by the desire to exploit nickel, the red gold of New Caledonia, which represents over a quarter of the world’s reserves.

Kassovitz portrays Legorjus agonizing over his choices, although he finally does follow the orders he has been given to participate in the attack, going against his personal values and morality, motivated ultimately by his sense of duty and love of his country. Dianou offers a direct parallel, of course, for he too is motivated by a cause and commitment to his country, Kanaky. And, like Legorjus, he is powerless in the face of French might. Both characters are portrayed with sensitivity and sublety. We end up sympathising with both.

French Minister Pons’ responses have their own ironies and complexities. When Legorjus calls on him to avoid the needless shedding of blood by negotiating rather than mounting an assault, Pons responds, “Sometimes it is the only way to restore order and morality.” This makes plain that New Caledonia’s fate was decided on the other side of the world, subject to higher political interests and time-tables.[7]

The characterization of the Kanak independence leaders and the film’s topicality are enhanced by the use of some of the actual protagonists’ family members as actors, showing how far New Caledonia has come since 1988. For example, Djubelli Wea, one of the hostage-takers who later shot and killed the revered Kanak leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou, is played by a close Wea relative, Macki. Members of the Wea family took on a number of other roles. The FLNKS figure, Franck Wahuzue, is played by respected Kanak writer Pierre Wakaw Gope.

The dignity and wisdom of Kanak tradition and custom, and of the Kanak elders, are successfully conveyed and contrasted with French duplicity. The tactical planning session is a solemn occasion, with poorly dressed Kanaks standing around the elder, heads bowed, listening respectfully and speaking in turn. We are shown the importance of the symbolic cloth, “le manou.” The message of the elders is epitomized in the statement: “Le parole doit être respectée” (“one must keep one’s word”), a reminder to the French of unfulfilled promises.

This resonates as we recall Legorjus’ promises to Alphonse Dianou that his men would not be killed, and then see him take part in the assault that killed most Kanak hostage-takers (including Dianou), and the subsequent gratuitous executions of Kanak prisoners by French troops. At one point in the fray, we hear a French soldier shout out: “Surrender now, I give you my word as a French officer that you have nothing to fear,” highlighting the extent of the betrayal, not only of Legorjus’ pledge but of French honour. Finally at the end of the skirmish, the dying Dianou tells Legorjus: “ My men… you promised me.” Nonetheless Legorjus concludes that he must stand by what he did, because “if the truth hurts, lies kill.”

There are other betrayals (for example, of Legorjus by Minister Pons) but assuredly the key message of the film is a reminder to the French and the pro-France forces in New Caledonia that their promises under the Noumea Accord – including the key promise of the long-deferred referendum on independence – must be fulfilled.

Mathieu Kassovitz, Director, L’ordre et la morale (2011), Color, 136 minutes, France, NRP Entreprise, Cofinova 7, Nord-Ouest Productions

* The author (denisemfisher@gmail.com) is Visiting Fellow, Australian National University Centre for European Studies, Canberra and is a former Australian diplomat who has served as Australia’s Consul-General in Noumea, New Caledonia (2001-2004), and as Australian High Commissioner to Zimbabwe (1998-2001).

- Philippe Legorjus, (and Jean-Michel Caradec’h) La morale et l’action, Paris, Éditions Fixot, 1990.

- Nic Maclellan, “Remembering the Ouvéa Massacre”, Islands Business, December 2011.

- Benoît Tangopi, blogsite probe.20minutes-blogs.fr accessed 1 December 2011.

- Statement 3 November 2011 by former Minister Bernard Pons, General Jacques Vidal, Colonel Alain Benson, and magistrate Jean Bianconi, on domtomnews.com. However, Michel Rocard, who headed the mediating mission sent by Mitterrand in 1988 which resulted in the Matignon Accords, has said that the film is “alas, accurate”, in Youtube interview of 9 November 2011.

- Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes 22 December 2011.

- Taken from 1996 and 2009 census figures, Institut de la Statistique et des études économiques website.

- There were other small ironies to Kassovitz’s production, not the least being the use of the office of the French Polynesian local President as the set for the French administration office, where Legorjus meets with Minister Pons. Irony, since those sumptuous quarters were built by a former local French Polynesian leader, Gaston Flosse, and in my extensive experience of visiting senior officials in all French Pacific territories, I have never seen a French government office as palatial as that built by Flosse.

Excellent film about how self-interested politicians can’t ever be trusted. Hope the Kanak nation get its independence asap!