John Connelly

University of California, Berkeley

In 1917, the young Polish Jew Charles (Karol) Lustiger left his home in Silesia and settled in a community of Polish Jews in Paris.There he met Gisèle-Lea, a young woman from his home town who happened to have the same last name. In 1925 they married and opened a hosiery shop in the eighteenth arrondissement. They had two children: Aron, born in 1926, and Arlette, born in 1930. Just before war broke out in August 1939 they entrusted son and daughter to a gentile family in Orleans for their safety. The following year, just before Easter, Aron expressed a desire to become Christian. In August, the bishop of Orleans took Aron into the Catholic Church, with the Christian name Jean-Marie. Because of his young age, Charles hoped Aron would return to Judaism after the war. Instead, Jean-Marie entered the seminary, and became a parish priest. In 1979, John Paul II tapped him to become bishop of Orleans.

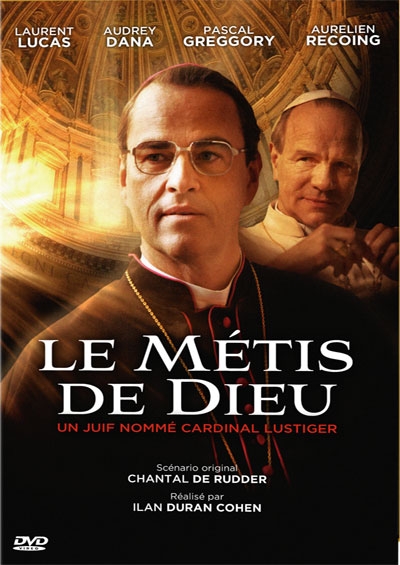

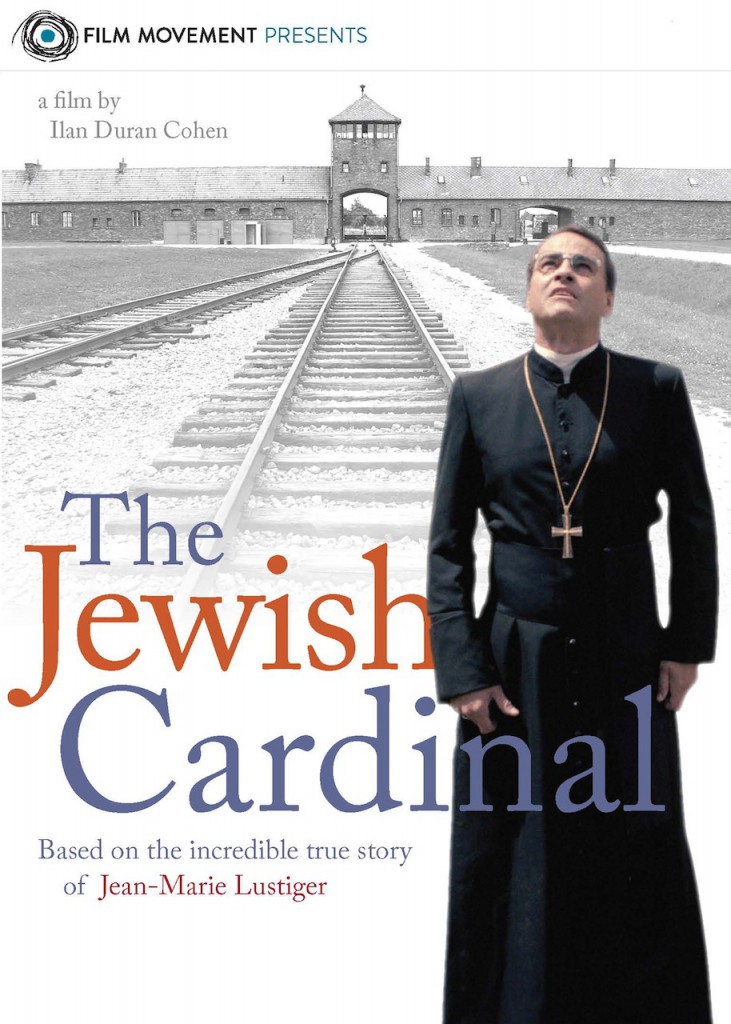

This event is the starting point for Ilan Duran Cohen’s The Jewish Cardinal (Le métis de Dieu). We see middle-aged Lustiger (brilliantly interpreted by Laurent Lucas) hunched over characters in a teach-yourself Hebrew book, preparing for an assignment to Jerusalem, when suddenly “providence” intervenes. He is told to report immediately to the Vatican’s representative to France (the Nuncio) where he receives news of the appointment. If a Pole can be the Pope, the Nuncio tells the stunned Lustiger, then a Jew can be a bishop.

This event is the starting point for Ilan Duran Cohen’s The Jewish Cardinal (Le métis de Dieu). We see middle-aged Lustiger (brilliantly interpreted by Laurent Lucas) hunched over characters in a teach-yourself Hebrew book, preparing for an assignment to Jerusalem, when suddenly “providence” intervenes. He is told to report immediately to the Vatican’s representative to France (the Nuncio) where he receives news of the appointment. If a Pole can be the Pope, the Nuncio tells the stunned Lustiger, then a Jew can be a bishop.

Jean-Marie is not a standard issue priest. He rides a rickety moped and smokes more tobacco than was the norm even for this period. He speaks his mind and his flock adores him. Few know his family history, which is not so much a guarded secret as nobody else’s business. Yet thanks to his appointment to bishop Lustiger’s “background” is now front-page news. The Pope made sure that the new bishop’s conversion from Judaism is mentioned in the announcement. Charles, still running his shop, has a theory: the Vatican believes that the only good Jew is a convert. He has not broken with Jean-Marie but their relations are strained. (Gisèle was murdered at Auschwitz in 1943.[1]) In one shouting-match father accuses son of being ashamed of his Jewishness.

But Jean-Marie is not ashamed. He barges in on the offices of a Catholic newspaper that carried the story about his conversion and instructs the editor that he is not of Jewish background. He is Jewish! With his baptism he renounced nothing. The editor feebly explains that this is a “good story” that he has to tell, but Lustiger storms off. (He was known as Mgr. Bulldozer).

Complications mount. Charles’ last wish is for his son to say Kaddish at his gravesite. (He died in 1982.) Instead, Jean-Marie brings another family member to recite the prayers while he remains silent. There is no minyan. His Jewish niece Fanny is outraged, and vows never to exchange another word with this “hyprocrite.” Jean-Marie believes that a bishop cannot publicly belong to two worlds. He had to choose.

But he does not find peace. Constantly smoking, Lustiger explodes at anyone and everyone in his vicinity. (According to the filmmaker the real man was even more irascible.)[2] His next target is the Polish pope (played by Aurélien Recoing, who like the rest of the cast, is excellent). Charles had warned him: Poles suck anti-Semitism with their mother’s milk. At a first private dinner with John-Paul pouring vodka Lustiger echoes his father’s suspicions. “Holy Father, why exactly did you make me bishop?” The reasons have to do not with Judaism but with Lustiger’s combative and free-spirited resistance to secularization in the Paris milieu.[3] Though Lustiger is often (misleadingly) described as “conservative,” in this scene he promises the Pope that he will not become the Vatican’s “doormat.” Those words turn out to be just right.

Soon Lustiger is archbishop, then Cardinal of Paris, where he works hard at the Pope’s agenda, using radio and press to spread the Gospel to all those whom the Church has alienated. The Pope takes Lustiger as special advisor on trips abroad, for example to Poland in 1983.

Soon Lustiger is archbishop, then Cardinal of Paris, where he works hard at the Pope’s agenda, using radio and press to spread the Gospel to all those whom the Church has alienated. The Pope takes Lustiger as special advisor on trips abroad, for example to Poland in 1983.

Swallowing his fears, Lustiger makes a day trip to Auschwitz from nearby Krakow. What he finds is horrifying beyond expectations.The former death camp is a museum of the communist state, and the former blocks “exhibitions” for nations victimized by the Nazi regime. There is one for France, for Hungary, the Netherlands, Yugoslavia, and so on. In the late 1970s an exhibition opened for Denmark, and after that for the Jews.[4] On the day Lustiger appears, this Jewish exhibition (Block 27) is locked, however. Few seem to know why or care. The educated and sympathetic Polish priest who acts as interpreter cannot understand Lustiger’s rage. What is the “Holocaust”? Did not all nations suffer? (I picked up a brochure at the Museum in 1981 with the following text: “The concentration camp Auschwitz served the realization of the Fascist program of biological destruction of other peoples, especially the Slavic peoples.”[5]

For the audience, the real revelation occurs after Lustiger’s return home. He corrals his friend, archbishop Albert Decourtray of Lyon, and insists they go immediately to the airport chapel where he wants to make a confession. At Auschwitz, Lustiger admits, he could pray neither an “Our Father” of thanks to God, nor Kaddish for his mother.[6] Yet this sinful impiety signals a new conversion, or perhaps reversion. Just before his departure to Auschwitz Théo Klein, president of the Council of Jewish Institutions in France (CRIF), had asked Lustiger to be an advocate “for us.” Both men understand that “us” embraces the Cardinal.

In the next scene (from 1985), Decourtray tells Lustiger of Polish Carmelite nuns who have installed themselves in a former theater on the edge of Auschwitz I to pray for the dead. (The Nazis had stored poison gas in this building.) Jewish leaders object: Christianization of camps like Auschwitz will cause people to forget that the overwhelming majority of victims were Jews. Urged on by Klein, Lustiger flies to Rome and causes a hesitant pope to permit secret negotiations between Jewish leaders and four Catholic prelates (Lustiger, Decourtray, Belgian and Polish cardinals).[7] At the Swiss chateau Pregny (in 1986 and 1987) they work out a deal whereby the nuns must leave within two years, transferred to a spot in the city of Oświęcim, a reasonable distance from the camp.

But the nuns won’t budge. In 1988 they erect a 26ft. tall wooden cross near the “convent” and not far from Block 11, the death block. Lustiger, in flowing red regalia, descends upon an unsuspecting John Paul II in the tranquility of his retreat at Castel Gandolfo. The pontiff explains his hesitation to become involved. The important issue for him is the battle with Polish Communists for the souls of his countrymen. The atheist government had laid claim to Auschwitz as a symbol of Polish patriotism and for decades brainwashed Polish children. He must recapture it for Catholic Poland, and the nuns appear unwitting accomplices.The struggle to get them out is an unwelcome distraction.

But the nuns won’t budge. In 1988 they erect a 26ft. tall wooden cross near the “convent” and not far from Block 11, the death block. Lustiger, in flowing red regalia, descends upon an unsuspecting John Paul II in the tranquility of his retreat at Castel Gandolfo. The pontiff explains his hesitation to become involved. The important issue for him is the battle with Polish Communists for the souls of his countrymen. The atheist government had laid claim to Auschwitz as a symbol of Polish patriotism and for decades brainwashed Polish children. He must recapture it for Catholic Poland, and the nuns appear unwitting accomplices.The struggle to get them out is an unwelcome distraction.

Yet under Lustiger’s browbeating and evident grief the Pope relents and promises to release an edict causing the nuns to go. Viewers have a sense of closure and the film moves ahead to 2007, the year of Lustiger’s death. His last wish, he tells Fanny, is that Kaddish be said before his funeral at Notre Dame. The rabbis and priests can figure out the details.

In real life things were not so simple. The film portrays the Pope promising to eject the nuns in 1989, but in fact they did not leave (and he did not act decisively) until 1993. Perhaps the Vatican moves more slowly than suits a TV drama. There are other inaccuracies, some tiny. The Pope would not have served a French Cardinal vodka. We know nothing about what John Paul actually said to Lustiger, but would he have told him that his successor in Krakow, Cardinal Franciszek Marcharski, was a liberal “without a backbone”? What exactly was the Pope’s thinking about the convent? I could not find an answer in any of the leading biographies.

The filmmaker, Israeli-born French Jew Ilan Duran Cohen anticipates such questions in a frame shown before the credits. His film is fiction “inspired” by the life of Jean-Marie Lustiger. Yet he and screenwriter Chantal Derudder know a lot about the real Lustiger because they spent five years researching his life. And in fact, their approach is not so different from that of other writers who nestle fiction in actual history. If history fails so does fiction. I was enjoying Alice McDermott’s book Charming Billy (winner of the National Book award in 1998) until she portrayed two US soldiers as being released from the army after VE day in 1945. That almost never happened (they were kept for the anticipated invasion of Japan).The false history broke the spell of the fiction and I could not continue reading.

The filmmaker, Israeli-born French Jew Ilan Duran Cohen anticipates such questions in a frame shown before the credits. His film is fiction “inspired” by the life of Jean-Marie Lustiger. Yet he and screenwriter Chantal Derudder know a lot about the real Lustiger because they spent five years researching his life. And in fact, their approach is not so different from that of other writers who nestle fiction in actual history. If history fails so does fiction. I was enjoying Alice McDermott’s book Charming Billy (winner of the National Book award in 1998) until she portrayed two US soldiers as being released from the army after VE day in 1945. That almost never happened (they were kept for the anticipated invasion of Japan).The false history broke the spell of the fiction and I could not continue reading.

For me such a situation did not emerge in The Jewish Cardinal. Perhaps it would if I knew more of what actually happened. Let’s call the vodka a symbol for the Polish Pope’s outpouring of charisma. Not completely implausible and “true” in a deeper sense. And perhaps slavish attention to detail can disrupt the pursuit of deeper historical questions.

Cohen was attracted to Lustiger because of the problem of reconciliation: how did this man manage to “reconcile with himself, with his father, with the Jews and the Christians.”[8] Reconciliation became a problem for Lustiger because of a choice he made as a boy, and his refusal to annul that choice as a man. (We now know that Lustiger’s parents also went through baptism during the war, so that the bishop of Orleans could produce a document stating they were Catholic.) [9] The tension between Jewish and Christian identities in the born Jew approaches resolution only as he climbs to the top of a Christian institution. The more Catholic Lustiger became, the freer he was to act, if not as a Jew, then with the Jews. “By the death of his mother,” the Chief Rabbi of Paris said in 1981, Lustiger “is identified with the sorrow of our people.”[10]

Over the decades we see an evolution in bishop Lustiger’s views from reasoned but unfeeling defense of Christian positions to empathetic understanding – and propagation – of Jewish ones. “The relation of the church to the Vichy regime,” he wrote in 1987, “is the same as the general attitude of the French population in relation to Vichy, to the resistance and to the Germans. The history of this period remains obscure and painful; I am struck that it is almost impossible to approach it, even today.”[11] This may have been a defensible rendering of the past, but it was also deeply insufficient for a prelate of the French Catholic Church. Ten years later Lustiger inspired and promoted a very different declaration by French bishops read at the deportation camp Drancy, from which Gisèle Lustiger had been deported:[12]

Although courageous actions in defense of persons were not lacking, we must acknowledge that indifference largely prevailed and, in the face of the persecution of Jews, especially the multi-faceted anti-Semitic laws passed by Vichy, silence was the rule and words in favor of the victims the exception…

Today we confess that silence was a mistake. We also acknowledge that the Church of France at that time failed in its mission of educating consciences and that she thus bears with the Christian people the responsibility of not having helped rescue in the early stages when protest and protection were possible and necessary, even though there were numerous acts of courage later on. …

We acknowledge this reality today because this failure of the Church of France and its responsibility toward the Jewish people are part of its history. We confess this sin. We beg God’s forgiveness and ask the Jewish people to hear our words of repentance.

Henri Hajdenberg, Klein’s successor as president of CRIF, thanked the bishops; their words were “without compromise, without concession. Your request for forgiveness is so intense, so poignant, that it cannot but be heard by the survivors and their children.”[13]

One does not have to be Jew or Christian or adherent of any religion to follow Lustiger on his path of reconciliation. Cohen the storyteller takes us along for the journey, and more deeply into Lustiger’s life than a historically accurate documentary could.The haunting loss of his mother, portrayed searingly on the screen, helped elicit what biographer Henri Tincq calls “paroles inouïes”[14] spoken at Drancy, words never heard before but necessary for French bishops and the French church. The message of solidarity appears universal.

But a historian might note that the message is also particular. Virtually everyone in the Catholic hierarchy who engaged meaningfully for a reconciliation with Judaism before the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s was, like Lustiger, a convert, a person whose life produced tension, tension that became unbearable as he or she sought to mourn dead Jewish parents and relatives as Christians. Until 1965 Christian theology taught that the Holocaust was punishment by God for Jews’ “lack of faith.” The Catholic priest who helped draft the Vatican II document that broke with this theological anti-Judaism had lost his mother at Auschwitz. Like Lustiger he was also a convert, and like Lustiger, somehow felt he continued to be Jewish. Though he helped give the Church new language, he had no words to capture his own situation.

Late in life this priest, John Oesterreicher, in retirement at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, happened upon writings of Jean-Marie Lustiger that gave him language to understand himself. Stored away in Oesterreicher’s private papers one can find a Xerox of an interview with Cardinal Lustiger gave to Israeli journalists in 1981: [15]

I never claimed to be at the same time a good Jew according to the requirements of the rabbis and a good Christian according to the requirements of the church. But I am sure you understand that I cannot repudiate my Jewish condition without losing my own dignity and the respect I owe to my parents and to all those to whom I belong; that is true both in times of persecution and in times of peace… what I can say is that in becoming a Christian I did not intend to cease being the Jew I was then. I was not running away from the Jewish condition. I have that from my parents and can never lose it. I have it from God and He will never let me lose it.

The totality of humanity according to God’s plan is made up of Israel and the nations, who are to be finally united in the one and only Covenant. If you put things that way, it is clear that the last days have not yet been fulfilled… the figure of the messiah is a hidden one. Christians tend to forget sometimes that they are still waiting for the coming in glory of their Messiah…Israel on the other hand must remain faithful as long as the times are not accomplished; it is still loved by God because of his election and because of the Patriarchs. God’s gifts and his call cannot be abolished.

In the margin of the section on Israel remaining “faithful” Oesterreicher had impressed a thick exclamation mark. Lustiger had given him a way of making sense of history, but also of himself. Whether or not we can calls Lustiger a revolutionary as Cohen does, he used his formidable intellect and irrepressible personality to push to fruition certain obscure teachings worked out by theologians like Oesterreicher, officially correct, but all but unknown to the Catholic flock. In a sense what he achieved was reconciliation of the Church with itself.

Ilan Duran Cohen, Director, Le métis de Dieu [The Jewish Cardinal], 2013, Color, 96 min, France, A Plus Image 4, Arte France, Arte, CNC, Euro Media France, Fugitive Productions, Scarlett Productions, TV5 Monde.

- She was arrested in Paris in September 1942 for not wearing the “Jewish star.” Henri Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger: Le cardinal prophète (Paris, 2012), 47.

- “The Jewish Cardinal Opens 17th UK Film Festival” The Times of Israel, 30 October 2013.

- Lustiger said in 1981: “je dirai que mon origine juive n’a sans doute pas déterminé le choix du pape, mais une fois ce choix arrêté, elle a certainement du contribuer a ce qu’il s’obstine a me nommer, pour peu que cette origine juive lui ait été présentée comme une objection.” Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger, 159

- (That occurred in 1978.)

- Danuta Czech, “Das KL Auschwitz als Vernichtungslager,” in Kazimierz Smolen, et al, eds., Ausgewählte Probleme aus der Geschichte des KL Auschwitz (Verlag Staatliches Auschwitz Museum, 1978), 56.

- After returning, he issued a statement, co-signed with Decourtray: “En ce lieu ou la cendre des victimes est mêlée pour toujours a la terre et a la mémoire d’un peuple, ou la terre crie de l’offense qui lui a été faite, on ne peut que faire silence.” La Croix, 25 June 1983, cited in Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger, 185.

- Daneels of Brussels and Macharski of Krakow.

- He originally wanted to entitle the film “Reconciliation,” as he explains in this interview.

- Henri Tincq calls it a “baptême de complaisance,” and comments that “La suite des événements montrera que ce certificat n’aura pas été d’un grand secours pour les parents du futur cardinal.” After the war, Charles tried to obtain a nullification of the baptisms of his children. Aaron Jean-Marie refused, claiming that he had not been “forcé par les circonstances de l’Occupation et les premières mesures antijuives de Vichy.” In school he continued to refer to himself as Aron, while his schoolmates called him Jean-Marie. Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger, 41

- Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger, 163.

- Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger, 201.

- “Declaration of Repentance by Roman Catholic bishops of France,” September 30, 1997 at

- http://www.sacredheart.edu/faithservice/centerforchristianandjewishunderstanding/documentsandstatements/declarationofrepentancebytheromancatholicbishopsoffranceseptember301997/

- Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger, 198.

- Tincq, Jean-Marie Lustiger, 197.

- “Christians, Jews, and Cardinal Lustiger,” The Catholic Digest, August 1986, 61, 66. The original appeared in the Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth 6, 15, 21 January 1982; cited in Jean Duchesen, ed. Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger on Christians and Jews (Paulist Press, 2010), 1. For more on Oesterreicher, see my From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933-1965 (Harvard UP, 2012).