Julie Kalman

Monash University

Perhaps it is the heightened effect of reviewing his book, but Robert Harris’s An Officer and a Spy seems suddenly to be everywhere. It has been reviewed in the mainstream press here in Australia just in time for summer holiday reading. The Guardian’s yearly parade of writers and critics listing their book of the year had journalist Simon Hoggart describing the novel as “taut and exciting […] gripping,” and this from a book “where you know the ending” before you pick it up.[1]

Harris has clearly crafted the story of the Dreyfus Affair into an appealing form. Of course, the Dreyfus Affair is the sort of tale novelists dream of. It contains a powerful combination of strong personalities and great drama. Indeed, the only personality in this story that does not leap off the page is that of the protagonist: the man who gives his name to the case. Alfred Dreyfus was famously diffident and reserved. He never satisfied the imagination of those who invested themselves in the Affair either to support or attack him. In many ways, this case presents more complexity than most fiction can handle.

So is Harris’s attempt to draw a story out of these elements successful? Harris does not try to impose a personality on Dreyfus. Rather, he chooses to make Georges Picquart his central character and narrator. Picquart was Alsatian, a graduate of Saint-Cyr, chosen to report on Dreyfus’s court martial to General Mercier. Picquart, generally viewed as an antisemite, was appointed to head the Statistical Section when his fellow Alsatian, Colonel Jean Conrad Sandherr, became ill. It was Picquart who first concluded that Dreyfus was innocent, and he is one of the more fascinating characters in this story. His persistent pursuit of the truth, even at the expense of his own career, reminds us that we cannot simply write off figures like him for their anti-Semitism.. There is no doubt that Picquart made unpleasant statements about Jews. Yet while he professed himself to have been “terrified” when he realised that Captain Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, and not Dreyfus, was the author of the incriminating document, he nonetheless brought the news of Esterhazy’s guilt to his superiors, and persisted in the face of their reluctance to receive his news. For this persistence, he was sent on missions, eventually ending up in Tunisia.

So is Harris’s attempt to draw a story out of these elements successful? Harris does not try to impose a personality on Dreyfus. Rather, he chooses to make Georges Picquart his central character and narrator. Picquart was Alsatian, a graduate of Saint-Cyr, chosen to report on Dreyfus’s court martial to General Mercier. Picquart, generally viewed as an antisemite, was appointed to head the Statistical Section when his fellow Alsatian, Colonel Jean Conrad Sandherr, became ill. It was Picquart who first concluded that Dreyfus was innocent, and he is one of the more fascinating characters in this story. His persistent pursuit of the truth, even at the expense of his own career, reminds us that we cannot simply write off figures like him for their anti-Semitism.. There is no doubt that Picquart made unpleasant statements about Jews. Yet while he professed himself to have been “terrified” when he realised that Captain Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, and not Dreyfus, was the author of the incriminating document, he nonetheless brought the news of Esterhazy’s guilt to his superiors, and persisted in the face of their reluctance to receive his news. For this persistence, he was sent on missions, eventually ending up in Tunisia.

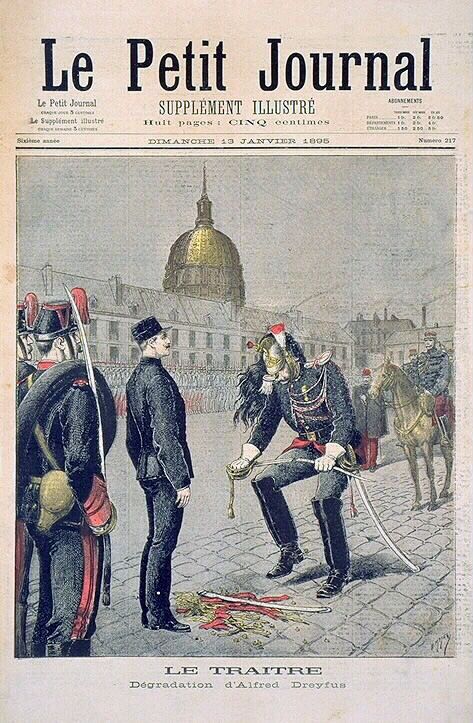

Harris picks up on one aspect of Picquart’s story. After Dreyfus was found guilty of treason, and before he was shipped off to Devil’s Island, he was subjected to a public degradation, where he was stripped of his insignia, and his sword was broken in two. Harris opens An Officer and a Spy with Picquart reporting to Mercier, Minister of War, on the degradation. But he fills out Picquart’s character, too. Harris gives him a difficult invalid mother. Picquart struggles with baser instincts. His mother is a burden, but he loves her. Picquart is also given a mistress, his childhood friend and sweetheart Pauline. At one point he takes a younger lover, and reflects on the fact that Pauline, at 40, gets undressed in the dark, while Blanche, at 25, basks in her nakedness. Were these signposts? Are we being prepared for Picquart’s other struggles? Is the existence of an invalid mother a way for the reader to identify with Picquart, while his later adventures might not be?

Harris seeks, too, to take the reader inside the army. He lets officers such as Picquart’s colleague at the Statistical Section, Henry, Minister of War, General Auguste Mercier, Deputy Chief of Staff Gonse and Chief of Staff Boisdeffre speak their minds, and in this way explains why they viewed Dreyfus as the perfect traitor. After all, if not Dreyfus, then it would have to be an insider, someone that these men were close to. If Dreyfus were guilty, then this rotten egg could easily be removed, and the army need barely be disturbed. In this way Harris vividly illustrates how Dreyfus’s Alsatian origins, his Jewishness, his personality, and his wealth combined to make him the ideal traitor. This is, perhaps, where the skilled novelist has license to do what the historian can’t, and generally won’t do. Harris brings the protagonists to life by giving them personal lives, putting words in their mouths, and letting them tell the story. This is how the Affair becomes a compelling tale in his hands.

His book’s claim to be compelling is made all the stronger because, as he tells us, it is based on historical research. He lists his sources in an appendix, and this lends his novel the authority of facts. Harris’s Picquart, Henry, and even Dreyfus are legitimated because of his reliance on George Whyte, Michael Burns, Jean-Denis Bredin, and Ruth Harris, not to mention his own primary research. This gives the reader a sense that history becomes intimate and knowable.

His book’s claim to be compelling is made all the stronger because, as he tells us, it is based on historical research. He lists his sources in an appendix, and this lends his novel the authority of facts. Harris’s Picquart, Henry, and even Dreyfus are legitimated because of his reliance on George Whyte, Michael Burns, Jean-Denis Bredin, and Ruth Harris, not to mention his own primary research. This gives the reader a sense that history becomes intimate and knowable.

My experience of An Officer and a Spy, however, was that there were jarring notes that undermined my ability to suspend disbelief. Harris puts platitudes in the mouths of his characters, designed to communicate the feel of the era to its witness, Picquart, and thus to the reader. Thus, for example, from his sickbed, retired Colonel Sandherr tells Picquart that “This is why we lost in ’70 – the nation is no longer pure.” (46) General Gonse tells Picquart that it is impossible to review Dreyfus’s conviction since this “would tear the country apart.” (243) These explanatory passages read as though they have been pasted on. Minor details, such as Harris having his characters refer to the judge in Dreyfus’s trial as “Monsieur President,” come across as affectation since they are incorrect. (Surely the more accurate appellation in this case would Monsieur le Président, as in the French, or, just simply, Mr President.) Details such as this one niggle, because this is a book that makes claims to authority on the basis of deep research.

More significant, though, is the way that Harris deals with Picquart’s attitude to Dreyfus and to Jews more generally. Anti-Semitism – the term itself only recently developed – was not uncommon in fin de siècle France. Jews were often co-opted into discourses that expressed anxiety over the nation’s virility, following the terrible loss of 1870-1, and in the face of the bourgeois liberalism that now ruled. Early in the book, Harris has Picquart mouth antisemitic tropes. When Picquart witnessed the degradation, he describes Dreyfus being paraded before the crowd, as “a Jewish tailor counting the cost of all that gold braid going to waste. If he had a tape measure around his neck, he might be in a cutting room on the rue Auber.” (13) Harris also quotes the Jewish journalist and Dreyfusard Bernard Lazare’s statement that “Picquart is energetically anti-Semitic.” In response, Picquart muses:

How am I to answer this? Perhaps by observing that if the true measure of a man’s character, as Aristotle says, is his actions, then mine have hardly been those of an energetic anti-Semite. Still, there is nothing like an accusation of anti-Semitism to get all one’s old prejudices flowing, and I write bitterly to a friend: ‘I knew that one day I would be attacked by the Jews, and notably by the Dreyfuses…’ Thus our beautiful cause descends into tantrums, disappointment, reproaches and acrimony.

This is where the fictional genre undermines the story. Picquart’s attitudes to Jews were complex, and it is this, rather than an ailing mother or two mistresses, that makes him interesting and important. Tropes about Jews, his own origins in Alsace, his military nationalism, and a sense of justice that comes through in his actions, all battle within him. What is compelling and significant about Picquart is this tension between himself and his milieu. The Dreyfus Affair did not fall and rise as a “beautiful cause.” Rather, it was a complex knot from start to finish, and Picquart personifies this. I learned this from countless hours steeped in the historical context. And it is precisely context that suffers in Harris’s work. The historian in me wants to explore Picquart’s complexity, and reflect on the many possibilities it offers for understanding late-nineteenth century France. However, rather than allow Picquart to be conflicted, Harris redeems him. This involves, first, a telegram from Clemenceau appointing Picquart Minister of War. Second, in what Simon Hoggart admiringly calls “a terrific anticlimax – if that’s possible,” Harris stages an encounter between Alfred Dreyfus and Picquart. Their intimate conversation forms the epilogue to the book. Picquart, now a General, receives Dreyfus in his office. Dreyfus is still the awkward, stubborn man he has always been. He has come to see Picquart to insist that he should be promoted, in recognition of the years of service that he missed. Picquart is obliged to reply, “in exasperation,” that this is not possible. Yet, appalled by the way their only conversation will end, Picquart suggests to Dreyfus that he himself had only attained his high rank because of his involvement in the Affair, and thus because of Dreyfus himself. Dreyfus, with the privilege of the final word replies thus: “No, my General, […] “you attained it because you did your duty.” (479) With this narrative artifice – the only time that Dreyfus speaks, other than to proclaim his innocence before hostile crowds – Harris has the spy offer the officer a path to redemption. Or is it Dreyfus the officer who makes the offer to Picquart the spy? One of the interesting things about Harris’s book is this ambiguity at its heart.

Yet Hoggart’s admiration of what he perceives as a climactic anticlimax is significant. (I don’t agree with his reading, I must say. To me, it reads more like quiet triumph. It is no accident that Harris gives Dreyfus the last word and that it is addressed to Picquart.) Harris has captured the inherent drama in this story. He offers us insight into the psychology of the main characters, which comes to life in his skilled hands. He has magnified the strong personalities, and made Picquart central, accessible and just likeable enough to carry us through. Yet Harris’s complexity is not that of an historical work, and here lies the tension between the response of a fiction lover and that of an historian, between the ways in which Harris’s book does and doesn’t work. His is not the complexity that an historian would seek to bring to light: the interaction between people, events, and their context. In this sense, fiction cannot trump historical research.

However, there are ways in which An Officer and a Spy supplements the historical narrative. The give-and-take between these different aspirations to convey different sorts of truths is what made Harris’s book a frustrating read. But this tension also makes An Officer and a Spy a useful way to think about the ways in which historical writing and fiction can overlap, compete, and complement one another.

- The Guardian, 23 November 2013.

Robert Harris, An Officer and a Spy was published in England in September 2013 by Hutchison, and will be released in the United States on 28 January 2014 by Knopf