Marco Deyasi

University of Idaho

Cézanne et moi, the new film by director Danièle Thompson, is a lush period piece centering on the friendship of Emile Zola (Guillaume Canet) and Paul Cézanne (Guillaume Galienne). Thompson, best known for her comedies, has created a film that will appeal to viewers of shows like Downton Abbey. Like these series, her film presents an idealized view of the past, along with some dramatic and emotionally charged scenes. There are several montages of laughter, food, and companionship in the peaceful sunshine of Provence. Few viewers will be able to resist this vision of a pleasant and comfortable bygone age. At the same time, the film targets a more sophisticated audience through the casting of classically trained actors from the Comédie-Française (Guillaume Gallienne, Laurent Stocker, and Christian Hecque).

The film may prove less satisfying for an academic audience. For a film about a writer and a painter, it says very little about art. The focus is on the relationship of the two men who famously fell out with the publication of Zola’s novel, L’Œuvre, a critical look at both the conservative society of Aix-en-Provence and the avant-garde milieu of modern art. Zola’s thinly veiled failed painter, Claude Lantier, was drawn, as Cézanne was fully aware, from his own life.

The film may prove less satisfying for an academic audience. For a film about a writer and a painter, it says very little about art. The focus is on the relationship of the two men who famously fell out with the publication of Zola’s novel, L’Œuvre, a critical look at both the conservative society of Aix-en-Provence and the avant-garde milieu of modern art. Zola’s thinly veiled failed painter, Claude Lantier, was drawn, as Cézanne was fully aware, from his own life.

The film moves back and forth in time, showing us events in the lives of the two protagonists. The director connects these events, like the salon or the band of Impressionists into which Cézanne has problems fitting, and key artists like Manet and Monet. We see less of the literary scene and instead are privy to some of Zola’s frustration at the reception of his work, and finally his engagement in the Dreyfus Affair.

From the very first frames, the film sets up a visual equivalence between the fine arts (painting) and literature. We see a close-up of a writer scratching away on paper. A few minutes later, the camera focuses on paints being mixed on a palette. The logo design and opening credits reinforce the theme: the title appears on the screen like Cézanne’s signature marked on a canvas.

Both Zola and Cézanne were outsiders in aristocratic Aix. Cézanne’s father made a good living as a banker, but as “new money,” he was not part of the local elite. A scene in the film points to Zola’s own marginal position: his family is poorer than the Cézannes and an acquaintance tells the schoolboy that his last name is not French. He and Zola seem to have had Romantic visions of making it in Paris despite being misunderstood in the provincial town in which they grew up.

Early in the film, Cézanne’s passionate rejection of academic art is shown as he curses and denounces the old-fashioned aesthetics and subjects celebrated at the Salon (the annual art show that drew thousands) demonstrated in the paintings accepted by its jury. Manet is mentioned by name more than once, alerting the viewer to his historical role as the godfather of modern art and the model for younger artists. There are occasional references to Balzac, perhaps the literary equivalent for Zola to Cézanne’s Manet.

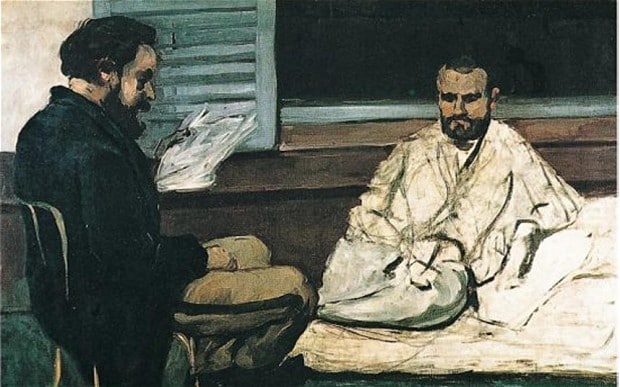

In a typical scene, Zola and Cézanne sit lazily in a small boat under the Provençal sun. Zola explains to his friend the concept behind a new series of novels that he envisions that would become Les Rougon-Macquart. Later, Cézanne is shown being inspired by the landscape and experience of life in Provence, finally finding his footing in the new plein air style. At one point, he stops and contemplates Mont Sainte-Victoire, glimpsed between some trees, reminding viewers of the famous series of paintings he would produce near the end of his life. In such moments, Thompson seems to be claiming that Zola and Cézanne’s art emerged primarily from a close observation of reality. While both men might have agreed, this allows Thompson to avoid the discursive and mediated character or all art. This is a conventional idea often repeated by my students. Hard questions about how art is constructed don’t come up, because in this vision, art directly represents reality. Visual and literary form, as well as cultural politics, end up ignored. As a result, Thompson reinforces a popular misconception about how art works. This is a missed opportunity.

In a typical scene, Zola and Cézanne sit lazily in a small boat under the Provençal sun. Zola explains to his friend the concept behind a new series of novels that he envisions that would become Les Rougon-Macquart. Later, Cézanne is shown being inspired by the landscape and experience of life in Provence, finally finding his footing in the new plein air style. At one point, he stops and contemplates Mont Sainte-Victoire, glimpsed between some trees, reminding viewers of the famous series of paintings he would produce near the end of his life. In such moments, Thompson seems to be claiming that Zola and Cézanne’s art emerged primarily from a close observation of reality. While both men might have agreed, this allows Thompson to avoid the discursive and mediated character or all art. This is a conventional idea often repeated by my students. Hard questions about how art is constructed don’t come up, because in this vision, art directly represents reality. Visual and literary form, as well as cultural politics, end up ignored. As a result, Thompson reinforces a popular misconception about how art works. This is a missed opportunity.

In fact, art—whether literary or visual—scarcely figures in the film at all. We see Cézanne attack his canvases in moments of frustration and rage, putting his foot through them several times. But we don’t see much in the way of the results of his psychological struggle. Only late in the film do we look over his shoulder to see the canvas he is working on. Likewise, there is a brief scene of Zola reading aloud from a novel to a small audience. The specific works that these men created, and for which they are renowned, are somehow absent. Thompson’s interest is clearly in the psychological struggles of artistic creation and the contrast between the two men. Zola achieved fame and success early on, whereas Cézanne took a long time to develop his style. At the end of his life, Cézanne was celebrated for the individuality of his “mark” or style as well as for incipient abstraction of his images. Both characteristics were essential to the Symbolist movement and central to modern art from 1885 onwards. [1]

In fact, art—whether literary or visual—scarcely figures in the film at all. We see Cézanne attack his canvases in moments of frustration and rage, putting his foot through them several times. But we don’t see much in the way of the results of his psychological struggle. Only late in the film do we look over his shoulder to see the canvas he is working on. Likewise, there is a brief scene of Zola reading aloud from a novel to a small audience. The specific works that these men created, and for which they are renowned, are somehow absent. Thompson’s interest is clearly in the psychological struggles of artistic creation and the contrast between the two men. Zola achieved fame and success early on, whereas Cézanne took a long time to develop his style. At the end of his life, Cézanne was celebrated for the individuality of his “mark” or style as well as for incipient abstraction of his images. Both characteristics were essential to the Symbolist movement and central to modern art from 1885 onwards. [1]

Because little is really known about Cézanne’s personal life, it is hard to disentangle the fictional character of Lantier from his real-life analog, especially because Zola’s creation became a model for later writers. [2] Cézanne’s surviving letters provide only fragmentary information about his personality and ideas. Later accounts, as Mary Tompkins Lewis notes, are unreliable because they are filtered through the authors’ own agendas and interests. This includes Zola’s writings and those of Joachim Gasquet, another of Cézanne’s friends and chroniclers. [3]

Indeed, Thompson has interwoven episodes from Zola’s novel into her ostensibly biographical film. In one scene, Cézanne tells Zola of a new idea for a painting, one that he will call Plein Air—the title of Lantier’s fictional masterpiece. Thompson thereby foreshadows later events, but she does so by mingling fact and fiction. As we know, Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe was Zola’s model, and Cézanne himself was inspired by Manet’s avant-gardism and rejection of the staid and conventional academic classicism that dominated the state-run Salon. Manet’s painting, like his later work, Olympia, was a succès-de-scandale that shocked the establishment with its frank nudity in modern settings.

The powerful scene where Cézanne’s wife, in tears, accuses him of loving his painting more than her is likewise taken from Zola’s novel. There, the fictional painter obsesses over an unfinished painting of a pious woman, hoping to manifest all of his genius in a single work. There are only faint echoes of the real Cézanne in such dramatic scenes.

In a remarkable set-piece at the Salon des Refusés, the alternative art show organized by the Impressionists to exhibit work that the Salon had rejected and that have become canonical, Cézanne is shown taking offence at the Philistines who mock modern art. He leaps at one, attacking him and they fall down in a tangle of limbs. Here, the director has taken liberties for the sake of drama, rendering physical what was otherwise an aesthetic and philosophical disagreement.

The Cézanne we see in this film is rude and foul-mouthed, aggressively antagonizing friends and family. Such an interpretation comes, in part, from the subjects of his early paintings, which are figuratively and visually dark. They include violent and overtly sexual subjects like The Rape, which Lewis has identified as depicting Pluto abducting Proserpina. [4] In A Modern Olympia, Cézanne’s attempt to out-do Manet, he represents the sexualized subject matter of modern prostitution, while including a self-portrait that hints at his own predilections. There is some evidence for this. Letters dating from when he was a schoolboy show his interest in lurid sexual subjects and reinforce the impression that his early art demonstrated the same fascination. Cézanne did indeed behave disagreeably, especially in Paris. [5] He adopted an exaggerated Provençal accent, cursed, and wore shabby, unfashionable clothes. He seems to have reveled in rebellion and defiance, acting out the stereotype of the uncouth hick. Some of his volatility perhaps reflected the persistent self-doubt revealed in his letters and his acute sensitivity to criticism of his art. When in Provence, however, Cézanne was polite and cordial, unlike what we see in the film. [6] Cézanne’s self-presentation might reflect Courbet’s, the Realist painter from the Jura who presented himself similarly in the Paris of the 1850s. While Manet was the consummate refined city-dweller, Cézanne patterned his early career on Courbet’s by rejecting the Salon and the aristocratic ideology behind it. But Cézanne’s apparent hatred of Paris might also have expressed a rising Provençal nationalism, embodied most significantly in the career and works of Frédéric Mistral who came to prominence when Cézanne was young.

Later in life, Cézanne would refer to his early paintings done with a palette knife as his manière couillarde. The crudeness of this expression points to the raw virility that the painter no doubt imagined was the source of his talent. Zola agreed. His letters show that he associated original and avant-garde artists with masculinity. [7] Cézanne thereby fashioned himself as a kind of intuitive, unsophisticated artist—a framing that seems to point the way towards later artists like Picasso who also celebrated virility and spontaneous creativity.

Cézanne has usually been understood in relation to subsequent developments in abstract (non-representational) painting. As an art historian, I sometimes find it hard to look at Cézanne’s work and not see glimmers of Picasso and his revolutionary aesthetic. Early critics and artists like Maurice Denis and André Lhote agreed that Cézanne was a precursor of modern painting, even if Cézanne himself did not fully achieve the greatness that he sought. [8] Cézanne’s posthumous reputation was cemented around the time of his death. A major retrospective show of his art in 1907 famously influenced the Cubists.

The final scene of the film shows Zola returning to Aix-en-Provence, celebrated by the locals. Cézanne, by then a recluse, rushes to greet his old friend and perhaps mend their friendship. But as he stands in the crowd that has collected around the famous author, he overhears Zola give his verdict that Cézanne was “an aborted genius.” Once again, Thompson has taken a text (Zola’s line appeared in a review) and turned it into an oral statement that can be communicated more easily on screen. We and the camera anxiously follow the painter as he huffs and puffs his way into town. We see his face fall as he hears his former friend’s dismissive judgement. It’s good cinema that tugs on the viewers’ heartstrings, but it’s not the way it happened.

The end credits roll over a montage of Cézanne’s paintings, ones that slowly morph from a view of Mont Sainte-Victoire into a painting of it, morphing further into other paintings. As before, the director seems to be saying that art emerges directly from the temperament of the artist as s/he contemplates reality itself.

Overall, Cézanne et moi is too episodic. Despite the highly divisive politics of the late-nineteenth century, major historical events are addressed with a mere remark or two. For instance, the Franco-Prussian war and the establishment of the Third Republic are dispatched through Zola’s mention that he is a republican. The Dreyfus Affair is addressed as airily. Blink and you’ll miss it. There is no discussion of how Zola or Cézanne engaged with their world. The former’s politics are alluded to in his criticism of literature’s failure to represent the workers. The cultural politics of the latter are absent, despite easily available information of how they tapped into politically conservative strands of Symbolism. [9] The politics that do appear are consistent with a twenty-first century celebration of French national culture. Zola and Cézanne come across as representatives of le patrimoine, with this film as a respectful tribute to them and to the culture that made France great. While such a position may be part of the current political debate over French identity in the face of increasing diversity, it doesn’t tell us much about how these particular individuals made France great. Thompson’s film has little to say about why we should continue to study Cézanne and Zola.

Danièle Thompson, Director, Cézanne et moi (2016), France, Color, 117 min, G-Films, Pathé, Orange Studio, France 2 Cinema, Umedia, Alter Films.

NOTES

- Richard Shiff’s classic study, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1984), remains essential for understanding art at the end of the century.

- Aruna D’Souza, “Paul Cézanne, Claude Lantier and Artistic Impotence,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol. 3, no. 2, Autumn, 2004.

- Mary Tompkins Lewis, Cézanne (London: Phaidon, 2000), 4.

- Richard Verdi, Cézanne (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), 34.

- Lewis, 63.

- Nina Athanassoglu-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence: The Painter in his Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 19.

- Athanassoglu-Kallmyer, 26.

Richard Shiff, “Mark, Motif, Materiality: The Cézanne Effect in the Twentieth-Century,” in Critical Readings in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, ed. Mary Tompkins Lewis (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). - Paul Smith, “Joachim Gasquet, Virgil and Cézanne’s Landscape: ‘My Beloved Golden Age’”, Apollo, CXLVII/439, October, 1998, 11-23.