Robin Walz

University of Alaska Southeast

It is fabulous news for history teachers and students alike that two of French illustrator Jacques Tardi’s World War One comics, C’était la guerre des tranchées and Putain de guerre!, have been published in English translation by Fantagraphics Books. Having taught both of these books over the past two academic years, it is my experience that the accuracy and visceral imagery of Tardi’s comics have the capacity to invoke a powerfully felt immediacy in today’s undergraduates about the post-traumatic stress of the poilu, the rank and file French foot soldier. I would like to suggest that Tardi’s antiwar comics supersede the reading of classic antiwar novels and even the screening of canonical films about the Great War. The first requires students to conjure up an ever-receding historical sensibility to feel the powerful emotions the authors aimed to convey; the second lock audiences within the limited duration of the film. At their best, comics get to “have it both ways”: flexible duration and a mix of word-and-image that rests upon the reader’s ability to observe and dwell on detail, to interpret the juxtapositions of media, and to follow a narrative from panel-to-panel and page-to-page sequences. And Tardi is a master of the comics medium.

Tardi belongs to the post-WWII generation of illustrators who pushed the French comics genre, broadly referred to as bande dessinée or BD, in a more sophisticated, adult direction.[1] A graduate of the École nationale des Beaux-Arts (Lyon) and the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs (Paris), Tardi began his career drawing covers and writing original stories for the weekly Pilote, and soon after for other popular comics periodicals such as BD, À Suivre, and Charlie Hebdo. His breakthrough comic book was Adèle et la Bête, published in 1976, and his popular “Les Aventures Extraordinaires d’Adèle Blanc Sec” series grew to nine folio editions (Casterman, 1976-2007).[2] In addition to original titles, Tardi has also collaborated with novelists, adapting polars and novels into graphic form: hardboiled detective and crime novels by Léo Malet, Jean-Patrick Manchette, and Didier Daeninckx, as well as the historical novel Le cri du people by Jean Vautrin about the Paris Commune of 1871 (Casterman, 4 vols., 1999). Tardi has received multiple awards for his comics and artwork, including the Grand Prix de la ville d’Angoulême in 1985 and two Eisner Awards in 2011 for It Was the War of the Trenches.

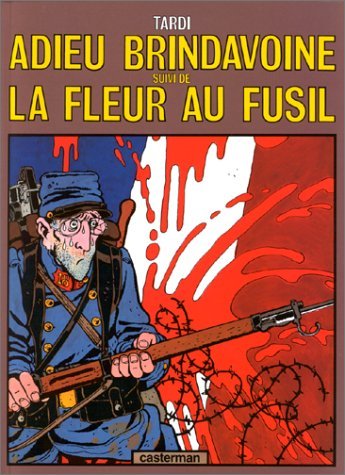

Throughout his career as a graphic artist and illustrator, Tardi has been preoccupied, if not obsessed, with the traumatic effects of the Great War upon ordinary soldiers during and after the conflict. This began with Adieu Brindavoine, a full color comic serialized in Pilote 1972-1973. Its subject was an amateur photographer named Lucien Brindavoine who unsuspectingly becomes entangled in a series of international espionage adventures on the eve of the war. Returning to the character in La Fleur au fusil (“With a flower in his rifle”), published in Pilote the following year, Tardi transforms the naïve Brindavoine into a hapless French infantryman already traumatized a few months into the war. (figure 1).[3]

His story continues in Le Secret de la salamandre, the sixth volume of the Adèle Blanc-Sec series. In 1916 the war-weary Brindavoine cuts and infects himself in the trenches, hoping to become ill enough to be sent home. Two days later, he passes out in No Man’s Land and awakens in a hospital bed to discover that his gangrenous forearm has been amputated. Discharged as a mutilé de guerre, he returns to Paris and sinks into lethargy and heavy bouts of drinking.

Along with developing Brindavoine’s story, Tardi produced an antiwar graphic novel in black and white titled La Véritable histoire du soldat inconnu (“The True Story of the Unknown Soldier,” Futuropolis, 1974). In this fantasy, an unknown man, a fiction writer of some sort, traverses dream landscapes that include a number of brothels, each inhabited by sexually threatening women, including “Josiane l’Éventreuse” (“Josiane the Ripper”). His nightmarish journey ends in the Passage Pommeraye in Nantes where he encounters a masked, naked old woman in furs, whom he recognizes as La Mort Volante (“Flying Death”), the title of his own novel. The old woman’s skeletal image explodes as the man cries out, “My head!” The panels move from the author being shot in the head to representing him as a dead soldier in a trench. His nonplussed comrades, who have no clue who he is, agree that he must have been some stupid author. Tardi suggests that this may be the pitiful corpse placed in the “Tomb of the Unknown Solider” on the Champs-Elysées.

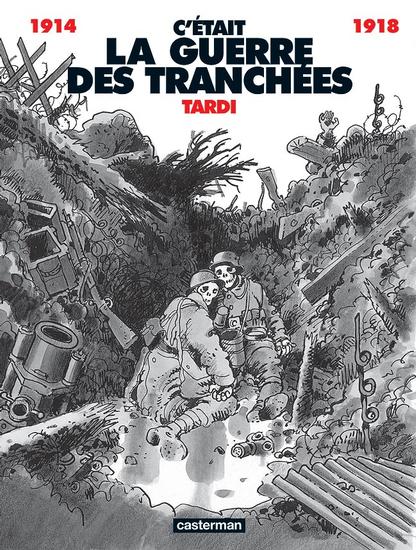

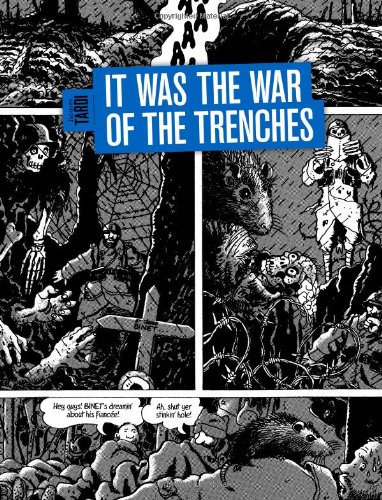

A decade later, Tardi returned to the Great War in C’était la guerre des tranchées (“It was the war of the trenches”), a series previously serialized in the monthly À Suivre (1982, 1993), and as a paper theater project called Le Trou d’obus (“The Bombshell Hole,” Imageries Pellerin, 1984) (figure 2). In contrast to his earlier First World War comics, Tardi adopts a more realist style, reminiscent of Hergé’s “clear line” technique of placing cartoon figures within highly detailed backgrounds. To guarantee the accuracy of the details, Tardi consulted World War One historian Jean-Pierre Verney about wartime photographs and used him as fact-checker. However, C’était la guerre des tranchées is not a documentary account of the war, but depicts the stories of ordinary French soliders: the sentry Binet who ventures out into No Man’s Land in search of his lost comrade, Faucheux; Private Desbois executed for cowardice, because he and other members of the 3rd Company Infantry returned to their trench rather than continue a futile assault; Private Huet, who offers himself up as sacrifice to German gunners to atone for having shot a Belgian woman and her children while exchanging fire with the Germans two years earlier; the happy-go-lucky Bouvreuil, who crafted souvenir trinkets for his pals in the trenches, entangled on barbed wire on No Man’s Land and shot by his comrades, even while his wife, a munitions factory worker, reads a postcard she has just received from him; and many more such individual stories.

Tardi’s purpose in telling these horrific and fatalistic tales about ordinary French soldiers is to convey the multiple and ambivalent feelings of these men, ranging from naïveté to cynicism, anger to resignation, passion to enervation, hope to despair. Tardi’s foreword, in Kim Thompson’s translation of the Fantagraphics edition, explains:

It Was the War of the Trenches is not the work of an “historian”… This is not the history of the first World War told in comics form, but a non-chronological sequence of situations, lived by men who have been jerked around and dragged through the mud, clearly unhappy to find themselves in this place, whose only wish is to stay alive for just one more hour, whose overarching desire is to return home… in one word, for the war to be over! There are no “heroes,” there is no “protagonist” in this awful collective “adventure” that is war. Nothing but a gigantic, anonymous scream of agony.[4]

Scores of men are slaughtered on the pages, and those who survive are permanently physically and psychologically scarred. Tardi’s graphic novel fits within the modern antiwar tradition of invoking sympathy for the victimized ordinary soldier, sent to slaughter by the generals and politicians. This bitter perspective is reinforced in two collaborations with polar writer Didier Daeninckx, the adaptation of Daeninckx’s novel, Le Der des ders (Casterman, 1997), and an original co-authored story, Varlot Soldat (L’Association, 1999).

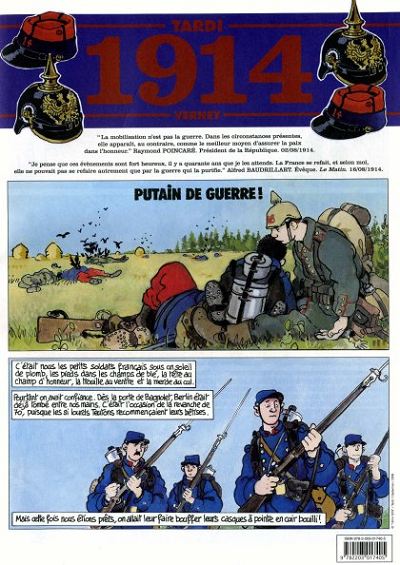

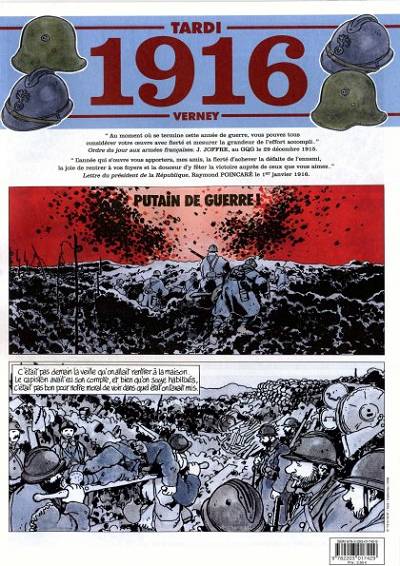

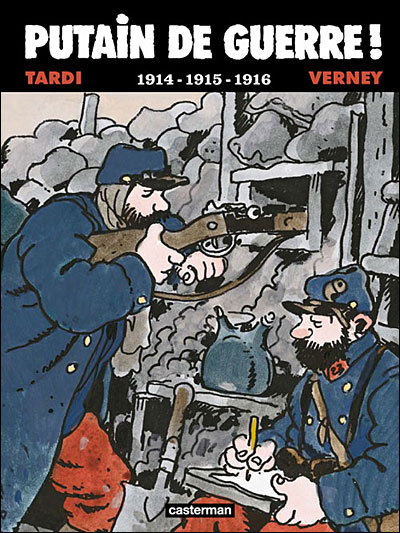

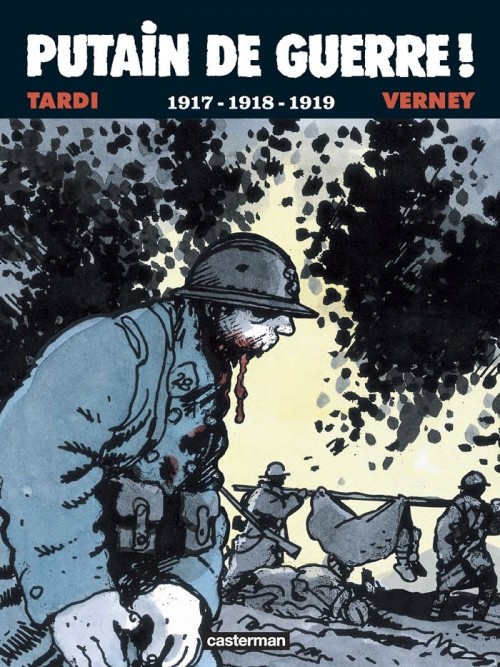

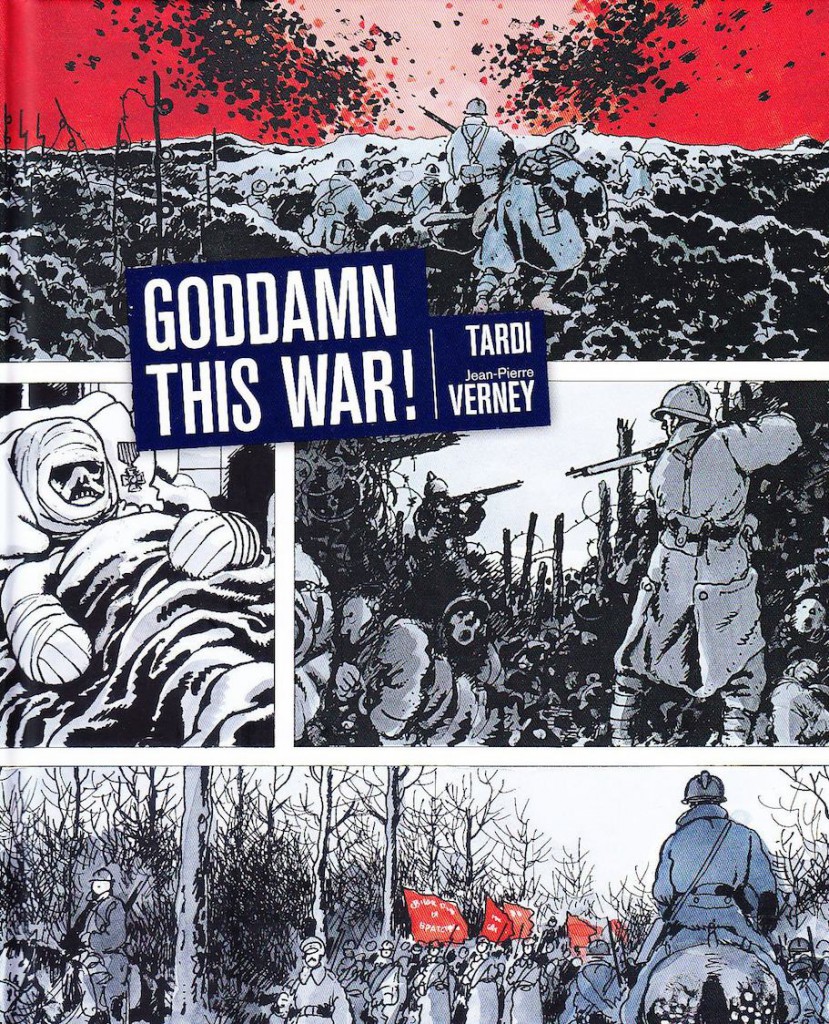

In 2008, to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the end of WWI, Tardi teamed up with historian Jean-Pierre Verney to produce a year-by-year chronicle of the war years, 1914-1919, called Putain de guerre! (“What a fucked up war!” or Goddamn this War! in the Fantagraphics translation) (figures 3 and 4).

Originally issued as a series of large-format newspaper tabloids, each installment of twenty pages was divided into a story written and illustrated by Tardi and a section of documentary photographs and that war-year’s chronology provided by Verney. Tardi blends his “Everyman-solider” approach with big-scale imagery and facts, which, together with Verney’s commentaries, offer a more comprehensive account of the First World War. While the focus remains primarily on the experiences of French troops, Putain de guerre! includes visual and documentary information about Germans, Belgians, Brits, and Russians, colonial troops in the service of Great Britain and France, and Americans, when they entered the conflict. Major battles are identified, some information is included about events beyond the Western Front (such as the Italian campaign and Gallipoli), and numerous scenes depict the hospitalization of the wounded. An unidentified first-person narrator tells the story, who is only fully revealed in the last panel of the final episode (although the visually discerning reader may guess which soldier it is earlier). This device helps to keep the larger visual drama of the war at the forefront. Tardi also adds to the authenticity of the story by peppering the written narrative with soldier’s argot from the period, whose meaning remains somewhat opaque to a contemporary reader. Following the newspaper-size installments, Putain de guerre! was issued by Casterman in two volumes, with Verney’s commentaries and an argot glossary at the end of each (figures 5 and 6).

For pedagogic purposes, what distinguishes Tardi’s First World War bandes dessinées is not his antiwar diatribes, which follow a century-long tradition in novels, memoirs, and movies, but the ways in which he skillfully employs the comics medium to deliver those messages. In this regard, the publication of It Was the War of the Trenches and Goddamn this War! is invaluable for English-speaking undergraduates, for, to my knowledge, no other World War One comics tell such stories so well (figures 7 and 8).

In order to fully explore the meaning of Tardi’s comics, students must first be introduced to the language of comics and the medium’s form, with analytical tools provided by such foundational works as Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art (Poorhouse Press, revised edition 1990) and Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (HarperCollins, 1993). Some of the formal features I discuss when using comics as a source in the classroom include: the basic elements of the cartoon panel (iconic characters, background images, expression marks, word balloons, captions, image and word juxtapositions), panel to panel transitions (separated by the “gutters” between panels), the sequencing of panels for storytelling purposes; page layout (single page, opposing pages, turning the page); the range from realism (detailed, individual) to cartooning (general, universal). Once these basic features are understood, in my experience, students readily engage in insightful analyses and develop sophisticated interpretations of what they see and read (far more quickly and perceptively than with either novels or movies).

Fantagraphics Books has performed a tremendous service by providing PDF samples of the English versions of Tardi’s First World War comics on its website. The excerpt from the opening pages of It Was the War of the Trenches, at this link, comes from Le Trou d’obus episode (the images are in black and white, although the original were colorized). The first three pages provide a visual background and information about trench warfare in 1917. On the fourth page the panels spiral in descending arcs to draw the viewer’s attention to the bottom of the page that introduces Binet, the story’s ordinary soldier, lying dead in the muddy bombshell hole, surrounded by horrific carnage and debris. The next page takes us back in time to Binet as a sentry, and the viewer adopts his point of view through the oval in the middle of the page that follows another soldier, Faucheux, moving across No Man’s Land. The large horizontal panel on the top of page 6 charts Binet’s hours of vigil, with a night view on the left and a day view on the right, with the devastation of No Man’s Land in-between. The layout of the page then switches to three vertical panels showing men in the trenches preparing to head into town for a few days’ leave, continuing on the next page. In another transition, on page 8, Tardi introduces the reader to a dozen portraits of the various “types” of foot soldiers in this company, skillfully drawn to individuate them while simultaneously retaining the simplified, “universal” Everyman approach. The next page contains a single frame –whose sheer size emphasizes its importance – with a portrait of Binet in the lower right corner. In a series of captions, Binet ruminates on his apartment building back home, on all the neighbors in that building for whom he feels disdain, on a France he detests composed of similar buildings and people, and he wonders why he should die for any of this. Nine pages into the comic book, the reader-viewer has already been bombarded with visual and textual information that arouses sympathy for the doomed Binet.

Goddamn this War! gathers all the war years in one volume. The 1914 episode is included in its entirety in the Fantagraphics Books PDF preview, at this link. Each page is composed of three horizontal panels in the “clear line” style and in full color, which accentuates the ridiculousness of the French army’s bright red and blue uniforms. The narrative is delivered through caption boxes, rather than by word balloons, adding a distancing effect that heightens the “objective” perspective of its anonymous narrator. Sometimes Tardi’s panels are mirrored on opposite pages to emphasis the parallel experiences of belligerent nations. Pages 4 and 5, for example, display the similar enthusiasm of patriotic crowds in August 1914 as their troops parade through the streets and then board trains, with the French on the left page and the Germans and Austrians on the right. Pages 8 and 9 reverse the perspective with the combatants facing off in an early field skirmish, with German gunners on the left and the French infantry on the right. Sometimes a single page tells a story, as on page 6 where the middle panel depicts animal slaughter sandwiched between panels showing “human meat” and slaughter on the battlefield. Pages 13-15 add an international dimension with the inclusion of allied Moroccan, British, Belgian, and Scottish troops, whose significance is conveyed by caption boxes more than by visual imagery.

Another significant formal dimension of Goddamn this War! is the gradual muting of colors into a monochrome landscape by the final two pages of the 1914 part. For the years 1915-1918, gray dominates and in this dreary world Tardi employs color to great effect. Large patches of pale yellow and bright red mean explosions, spent cannon shell casings, and body mutilations. The occasional appearance of color makes the target-images stand out among all the gray tones: the biplanes of “heroic” aviators are rendered in full color, Russians troops who refuse to continue fighting carry red flags, newly arrived Americans sport brown uniforms, and brightly colored medals are pinned on the ashen mutilés de guerre. The limited reintroduction of color in the midst of the gray tones serves a specific goal in the 1919 episode, suggesting that after the war, the world has only been partially restored and its participants have been permanently traumatized.

A few features distinguish this English translation of Putain de guerre! from Tardi’s original version, beginning with the combination of all six war years into one volume. The soldier’s argot that peppers the narration in Putain de Guerre! with a corresponding glossary have disappeared from this edition. Perhaps as a compensation, Fantagraphics Books has added an English translation of La Chanson de Craonne (“The Song of Craonne”), the anti-military song sung by French troops following the disastrous Chemin des Dames offensive in 1917 (banned in France until 1974), that in the original Tardi had referred to but not reprinted.[5] Jean-Pierre Verney’s documentary photographs and his commentary are included at the end under the title, “World War One: An Illustrated Chronology.” Verney’s war chronicle supplements the bande dessinée in important ways. It situates Tardi’s antiwar polemics within a full-blown historical context. Above all, Fantagraphics Books translation of Jacques Tardi’s comic books has reinvigorated the traumatic story of World War One for contemporary readers.

Jacques Tardi, It Was the War of the Trenches. Ed. and trans. Kim Thompson. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2010.

Tardi and Jean-Pierre Verney, Goddamn this War! Ed. Kim Thompson. Trans. Helge Dascher. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2013.

Illustrations

Figure 1: Cover of Adieu Brindavoine suivi de La Fleur au fusil (Casterman, 1979).

Figure 2: Cover of C’était la guerre des tranchées (Casterman, 1993).

Figure 3: Cover of newspaper format Putain de guerre! 1914 (Casterman, 2008).

Figure 4: Cover of the newspaper format Putain de guerre! 1916 (Casterman, 2008).

Figure 5: Cover of Putain de guerre! 1914-1915-1916 (Casterman, 2008).

Figure 6: Cover of Putain de guerre! 1917-1918-1919 (Casterman, 2009).

Figure 7: Cover of It Was the War of the Trenches (Fantagraphics Books, 2010).

Figure 8: Cover of Goddamn this War! (Fantagraphics Books, 2013).

- For recent treatments in English of the French comics industry, formal analysis and historical contexts, see: Laurence Grove, Comics in French: The European Bande Dessinée in Context (New York: Berghahn Books, 2012); Joel E. Vessels, Drawing France: French Comics and the Republic (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010); Mark McKinney, the Colonial Heritage of French Comics (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011); Charles Forsdick, Laurence Grove, and Libbie McQuillan, eds., The Francophone Bande Dessinée (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2005); and, Matthew Screech, Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), which contains a chapter on “New Visions of the Past: Jacques Tardi.”

- The first four Adèle Blanc-Sec stories have been translated and published by Fantagraphics Books as The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc Sec, Vol. 1 Terror Over Paris and The Eiffel Tower Demon (2010), and Vol. 2 The Mad Scientist and Mummies on Parade (2011).

- An English translation of Adieu Brindavoine and La Fleur au fusil is being prepared by Fantagraphics Books under the title, The Astonishing Exploits of Lucien Brindavoine (forthcoming 2013).

- Fantagraphics Books has included Tardi’s “Foreward” and “Special Thanks” to documentary historian Jean-Pierre Verney on its website, at this link.

- Many versions of La chanson de Craonne are available for downloading via internet vendors. I recommend the version sung by Eric Amado (1973).