Volume 2, Issue 2

The American love story with Paris, rudely interrupted by the “Freedom Fries” episode, has recently revived with a vengeance in the form of memoirs, scholarly analyses, and a string of “chick-lit” romances. It is our great luck that Woody Allen has chosen to ride the crest of this wave with a fond look at the city and the days when Americans came in droves to fulfill their artistic dreams. Although the phenomenon of Americans in Paris is two centuries old, the Lost Generation remains its most powerful embodiment, the huge success of the exhibition of the Stein family as art collectors [showing in San Francisco, Paris, and New York] being yet additional proof. In managing to bring this particular moment of the past and present together in so entertaining a fashion, Woody Allen has offered those of us who teach the history of Paris on North American campuses a great vehicle for discussion, as Jeff Jackson demonstrates. Anyone who presumes that the myth of Paris as a Bohemian haven for writers is dead and gone might take a look at Douglas Kennedy’s The Woman from the Fifth, “soon to be a major motion picture,” which offers a less rosy version of the transplantation. The fascination, one should note, is mutual, and the French remain as mesmerized by Manhattan as Americans by the City of Lights.

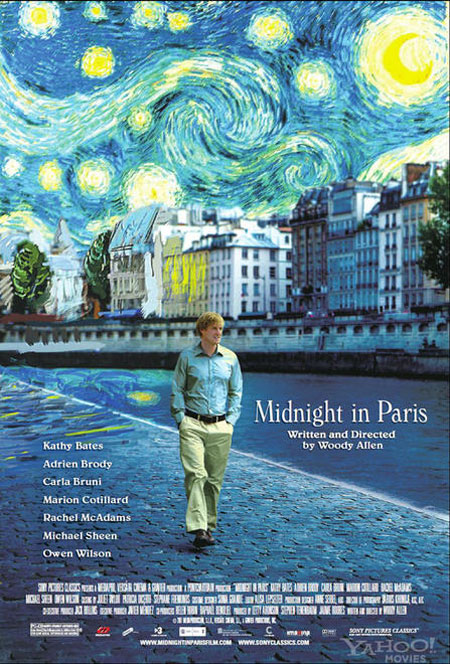

Midnight in Paris

Jeffrey H. Jackson

Rhodes College

Woody Allen is one of those rare American film directors who is widely appreciated by French audiences and critics. Perhaps it comes as no surprise that Allen would choose to craft a cinematic love letter to Paris. But Midnight in Paris is not about the city as much as it is about the American fascination with and romanticization of Paris. Allen employs the tales Americans have constructed about the City of Light to ruminate on larger themes of nostalgia, memory, and history. Paris provides the perfect backdrop for such an exploration, Allen implies, because the American imagination of Paris is bound up with these issues. Even Americans who have never been to Paris are somehow nostalgic about it.

The film begins as a satire targeted at some of the stereotypical Americans who visit Paris. Owen Wilson plays the “Woody Allen character,” Gil: a frustrated Hollywood hack screenwriter who yearns to become a serious novelist. He regrets leaving Paris many years earlier, but has now returned with his fiancée Inez (Rachel McAdams) and her parents, in hopes of drinking in some of the city’s beauty. For all his success in Hollywood, Gil is a would-be bohemian who longs for the artists’ inspiration of a garret apartment. He loves Paris in the rain for its beauty, while the people around him simply find it inconvenient. Unfortunately, Gil’s future wife and in-laws are the “ugly Americans” who go to Paris for business or shopping, but care about little else. They complain about the traffic, go to American movies, and see almost nothing of the city outside a few high-end retail destinations. They enjoy the luxurious aspects of Paris, but can’t wait to return to LA. When Gil mentions the idea of moving there, he is roundly ridiculed.

The film begins as a satire targeted at some of the stereotypical Americans who visit Paris. Owen Wilson plays the “Woody Allen character,” Gil: a frustrated Hollywood hack screenwriter who yearns to become a serious novelist. He regrets leaving Paris many years earlier, but has now returned with his fiancée Inez (Rachel McAdams) and her parents, in hopes of drinking in some of the city’s beauty. For all his success in Hollywood, Gil is a would-be bohemian who longs for the artists’ inspiration of a garret apartment. He loves Paris in the rain for its beauty, while the people around him simply find it inconvenient. Unfortunately, Gil’s future wife and in-laws are the “ugly Americans” who go to Paris for business or shopping, but care about little else. They complain about the traffic, go to American movies, and see almost nothing of the city outside a few high-end retail destinations. They enjoy the luxurious aspects of Paris, but can’t wait to return to LA. When Gil mentions the idea of moving there, he is roundly ridiculed.

Along the way, Gil and Inez run into another American couple, Paul and Carol (Michael Sheen and Nina Arianda) who make things worse. Paul is the “pseudo-intellectual” who believes himself an expert on all things French and is not ashamed to flaunt it. He gets into an amusing disagreement with a guide at the Rodin museum, played by French first lady Carla Bruni-Sarkosy, allowing Allen to ridicule another variety of American abroad. Allen’s mockery is not merely funny. These characters provide the foils for the film’s main conceit. On a series of midnight walks, Gil is whisked away by a 1920s roadster transporting him back to the era of the Lost Generation. Each evening, Gil the frustrated writer meets and learns from his literary and artistic heroes. He encounters F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Cole Porter, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, T.S. Eliot, and many others. Gertrude Stein (Kathy Bates) takes Gil under her wing, reads his manuscript — a tale of a man who works in a “nostalgia shop” selling trinkets from the past — and gives him advice about how to shape it into a better novel. She suggests he find an antidote to the meaningless of existence.

The emotional core of the movie is Gil’s romance with Adriana (Marion Cotillard), a lover of and model for Picasso. Here the film becomes a straightforward love story: the hero is engaged to the “wrong” woman but realizes it when he meets the “right” woman with whom he falls in love. Unfortunately for Gil, the “right” woman lives in the 1920s. His love for Adriana also serves as a metaphor for his (and Allen’s) feelings about the city: like Paris, she is beautiful, enigmatic, and everyone loves her, but he can’t possess her because she inhabits another time.

The scenes set in the past are often corny evocations of famous people; Hemingway spouts a string of Hemingway-isms about writing, truth, death. They are also effective because they fuel Gil’s romantic view of Paris in opposition to the “ugly Americans” with whom he spends time in the present. Nostalgia warps the past into what we want it to be, and Allen’s depictions of famous writers and artists are fantastical visions of how he (and maybe we) might like them to look and act if he were to ever meet them in person. Their very unreality is precisely their charm.

The central themes of nostalgia and myth-making about the past can lead to some of the most fruitful discussion for students since fantasies about Paris are still part of the experience of many Americans who go or dream of going there. Viewing this film alongside Hemingway’s books, Fitzgerald’s stories, or the work of other 1920s-era authors such as Janet Flanner or Malcolm Cowley, would be thought-provoking as would a reading of parts of Mark Twain’s much earlier satire of American travelers, Innocents Abroad. Including the French perspective on Americans in the 1920s from Georges Duhamel’s America the Menace or Paul Morand’s New York would also enrich the conversation about trans-Atlantic perceptions. Incorporating the work of several scholars who have written about the American fantasy of Paris as well as the realities of the 1920s would also be extremely instructive for students. Being an expatriate was never as simple or fun as Allen makes it seem. Brooke Blower’s Becoming Americans in Paris, Charles Rearick’s Paris Dreams, Paris Memories, Harvey Levenstein’s Seductive Journey, and Patrice Higgonet’s Paris: Capital of the World among several other works could help students situate the often difficult issues of expatriation and trans-Atlantic exchange in the early twentieth century while also complicating the questions Allen raises. Vanessa Schwartz considers Franco-American myth-making specifically in the medium of film in her book It’s So French! and a viewing of some of the “Frenchness” films she discusses, such as An American in Paris (1951), could help put Allen’s work within a richer cinematic context.

Ultimately, the film asks us to consider the question why does the dream of Paris still seem more powerful for Americans than the reality? This question is especially important since Allen engages in quite a bit of myth-making of his own. Paris in this film is remarkably unified, something established with the opening montage. Focusing on major landmarks and vistas, Allen jumps around the city showing each for a few seconds, thereby equating every part of the tourist’s Paris. Characters move quickly through the urban space as though every neighborhood were in close proximity. Students might ponder what Allen includes and excludes, both in the past and the present. For instance, there are relatively few ordinary French people in the film, an interesting omission which Hemingway also commits in A Movable Feast. It should also come as no surprise that this is a sanitized version of Paris. There is nothing troubling here, no banlieues, poverty, or construction. Nostalgia erases those elements of Allen’s experience. There are mentions of Pigalle, and one very brief scene in the area’s prostitute-filled streets. However, Allen does not acknowledge that Pigalle’s reputation as a sexually liberated zone was precisely why many American writers and artists traveled to Paris.

Perhaps Allen chose to focus on the 1920s because the Lost Generation shaped much of the twentieth century version of the American in Paris fantasy. His love of 1920s jazz is also well-known since most of his films open with a tune from that era, and Allen has been a successful working clarinetist with a band which plays New Orleans-style jazz (see the 1997 documentary Wild Man Blues about his band’s European tour). Ironically, there is almost no jazz performance, and very few African-Americans are depicted in the film despite their importance to the artistic scene. Paris in the 1920s was racially integrated in a way that the US would not be for decades. Gil and the Fitzgeralds make a quick trip to Bricktop’s where we see Josephine Baker dancing. However, we do not meet her, nor do we see any other jazz musicians or dancers; Sidney Bechet only shows up in the soundtrack. Students might read my book Making Jazz French, Tyler Stovall’s Paris Noir, or Matthew F. Jordan’s Le Jazz, or autobiographies by Bricktop, Bechet, or Langston Hughes and ask why Allen chooses to omit this part of the story.

By the end of the film, Allen has deflated much of the American in Paris nostalgia fantasy. Gil, perhaps finding the antidote to the meaningless of existence after all, realizes that he must live in the present, surrounded by the people and the problems of his own time. But Allen thoroughly embraces the ongoing belief in Paris as the place for writers, artists, and filmmakers to find inspiration. Gil leaves his fiancée, not for a woman but rather for the City of Light, where he decides to stay so that he can finish his novel. In many ways, Allen does here what he did for New York in his earlier films: the city becomes an integral character exerting a force larger than the people within it. Students might find an interesting comparison with how French filmmakers have depicted their own city in nostalgic terms, with viewings of Le Fabuleux destin d’Amélie Poulain and Paris je t’aime as the most obvious examples. But there are hundreds of films about Paris from which to choose since the city has been depicted from the beginning of motion pictures. Allen has not shown us a new vision of Paris, but he has delivered an entertaining one, which can inspire American audiences to reconsider their relationship with a city which seems both familiar and strange at the same time

Woody Allen, Director, Midnight in Paris (2011) Spain, USA/Color, Gravier Productions, Mediapro, Televisió de Catalunya (TV3), Versàtil Cinema, Running Time: 94 min.