Laura Mason

Johns Hopkins University

We first see a hand scratching mosquito bites. The image reminds us that Versailles was built in a swamp, setting the stage for the backstairs view of life in the royal palace that follows, and it serves as an apt metaphor for the bearer’s desire to know Marie-Antoinette. For it is that bearer’s frustrated effort to become indispensable to her seductive, self-absorbed sovereign that drives Farewell, My Queen’s subtle exploration of court life on the eve of its extinction. Like Chantal Thomas’ novel of the same name, Benoit Jacquot’s film follows the fictional Sidonie Laborde’s movement through a crowd of familiar historical figures during three increasingly tense days in July 1789.[1] As the queen’s reader, Sidonie is well placed to follow the confusion that is sparked by news of the Bastille’s fall, eavesdropping on her mistress, on the nobles who crowd the palace, and on the myriad underlings with whom she shares in the business of keeping the vast court going.

Jacquot represents this world as both strange and familiar. Farewell, My Queen was filmed at Versailles but takes its distance from a contemporary glamour to find the crowded, smelly palace that W.H. Lewis so memorably described.[2] Gray, badly-plastered stairways, a cluttered library that also serves as an archivist’s bedroom, and a chaotic kitchen annex where soldiers and servants chatter while gobbling food stand in sharp contrast to the warm elegance of the queen’s private apartments and the chilly beauty of the Hall of Mirrors. At the same time, Jacquot finds a contemporary touchstone, rendering the royals as celebrities. The king, in particular, appears a remote figure whom hangers-on struggle to glimpse, pressing up against the palace grillwork to watch him greet the people and dashing wildly through the Hall of Mirrors to see him leave council chambers.

Jacquot represents this world as both strange and familiar. Farewell, My Queen was filmed at Versailles but takes its distance from a contemporary glamour to find the crowded, smelly palace that W.H. Lewis so memorably described.[2] Gray, badly-plastered stairways, a cluttered library that also serves as an archivist’s bedroom, and a chaotic kitchen annex where soldiers and servants chatter while gobbling food stand in sharp contrast to the warm elegance of the queen’s private apartments and the chilly beauty of the Hall of Mirrors. At the same time, Jacquot finds a contemporary touchstone, rendering the royals as celebrities. The king, in particular, appears a remote figure whom hangers-on struggle to glimpse, pressing up against the palace grillwork to watch him greet the people and dashing wildly through the Hall of Mirrors to see him leave council chambers.

But the movie’s real subject is the queen and the noisy, nosy court that becomes a character in itself. The genius of Thomas’ perspective, which the film adopts, is to see Marie-Antoinette through the eyes of someone neither intimate nor remote. Previous films that have taken the queen as their subject– whether Sofia Coppolas’ Marie-Antoinette of 2006, or the 1938 melodrama of the same name with Norma Shearer– limited their capacity for critique by focusing too narrowly on the woman herself: asking viewers to identify with the queen’s travails at court, they can only mourn her as tragically misunderstood. Thomas and Jacquot, by contrast, produce a much more complex portrait by standing at a slight remove to find a Marie-Antoinette both seductive and obnoxious. When she turns her attention on Sidonie, she brims with affection and vulnerability that the younger woman drinks in. But the queen cannot focus her attention on anyone or anything for long. Satisfied in every whim, she seems fundamentally incapable of following an idea or even the single chapter of a book to its conclusion, flitting from subject to subject as her servants dance to keep up. We see too the self-absorption that such uncomplaining service fosters. By alluding to these qualities before the Bastille looms into view, Farewell, My Queen establishes them as elements of Antoinette’s character rather than mere responses to crisis, making visible her appeal and callousness without idealizing or demonizing.

Jacquot’s most notable departure from Thomas’ novel is to transform Gabrielle de Polignac from royal friend to lover. Although we don’t see the women embrace, there is plenty of heavy-handed suggestion: Polignac boldly marching from the queen’s apartments at dawn, Marie-Antoinette’s expression of fascinated desire, Sidonie’s visual positioning as surrogate lover when she gazes at Polignac’s naked body while the latter sleeps. The supposed relationship between Marie-Antoinette and Polignac adds a measure of suspense to a movie that occasionally drags, but it is not especially persuasive dramatically. Polignac is even more self-absorbed than the queen so that when we learn that she reputedly died of a broken heart after their separation, it hardly rings true. However, for those who use this film in the classroom, Jacquot’s version of Polignac’s role at court and his preference for allusion over illustration may spark interesting conversations about pornography against the queen and how it gained such purchase.

Jacquot’s most notable departure from Thomas’ novel is to transform Gabrielle de Polignac from royal friend to lover. Although we don’t see the women embrace, there is plenty of heavy-handed suggestion: Polignac boldly marching from the queen’s apartments at dawn, Marie-Antoinette’s expression of fascinated desire, Sidonie’s visual positioning as surrogate lover when she gazes at Polignac’s naked body while the latter sleeps. The supposed relationship between Marie-Antoinette and Polignac adds a measure of suspense to a movie that occasionally drags, but it is not especially persuasive dramatically. Polignac is even more self-absorbed than the queen so that when we learn that she reputedly died of a broken heart after their separation, it hardly rings true. However, for those who use this film in the classroom, Jacquot’s version of Polignac’s role at court and his preference for allusion over illustration may spark interesting conversations about pornography against the queen and how it gained such purchase.

As important as the queen herself is the court that vibrates around her. Here, the film beautifully visualizes two generations of cultural history by conjuring a material world in which oral and textual played equally important parts. We see the uncertain circulation of news as we follow Sidonie’s efforts to cadge information about events in Paris and we come to appreciate how little anyone really knows when she lingers in a dark hallway crowded with frightened court nobles. Moving among the shadows cast by candlelight, Sidonie listens as men and women who are literally and figuratively in the dark share word of what may have taken place at the Bastille and what might happen next. A few search for their names in a pamphlet that targets the “286 heads that must fall,” and one old man faints after finding his there.

The gossip and ephemera that populate this dark hall co-exist in the film, as they did in the eighteenth century, with the familiar books and frivolous journals that circulate in more brightly lit spaces. Sidonie’s status as a reader allows us to consider the prominence of texts in privileged lives, even those with the limited intellectual horizons of the queen. Sidonie’s dickering with lady-in-waiting Mme. Campan about whether a funeral oration or chapter two of Marivaux’s Vie de Marianne is more likely to improve Marie-Antoinette’s mood underscores both books’ intimate familiarity to everyone involved. When the queen loses interest in the one chosen and asks Sidonie to read from a journal de la mode instead, we begin to suspect just how much reading material was available. These and other scenes that allude to texts– the court historian’s crowded library– and material life– in the form of a subplot about a piece of embroidery that marchande de mode Rose Bertin solicits from Sidonie– make this an illuminating film. Even those concerned with the Revolution only in passing will find here an unusually rich representation of privileged culture.

It is as a film about the French Revolution, however, that Farewell, My Queen raises particularly interesting questions about fiction, genre and historical memory. Although director Benoit Jacquot remains tightly focused on July 1789, his film foreshadows the Terror through its characters’ allusions to popular violence after the taking of the Bastille and Marie-Antoinette’s fearful predictions of what will happen to the royal family if it does not flee. Seen from a historian’s perspective, such telescoping seems to endorse Simon Schama’s infamous dictum that “the Terror was merely 1789 with a higher body count” but this is more properly familiar literary license, which allows the event to resonate beyond itself.[3] There is too the film’s subject and mood: although we see Versailles with Sidonie, she is little more than a cipher who brings it into focus. The film’s real subjects are court and queen, and Sidonie’s regret at their passing suffuses its final moments. In this sense, Farewell, My Queen is like most films about the French Revolution in putting elites’ experience front and center. Whether Abel Gance’s Napoleon, André Wajda’s Danton, Eric Rohmer’s The Lady and the Duke, or Ettore Scola’s La Nuit de Varennes, recently reviewed here, “the people” exist as a backdrop for the trials and tribulations of falling nobles or rising bourgeois.[4] And this despite a historiography rich in popular actors and our common knowledge that the Revolution was driven by popular activism. Undoubtedly, this is because film makers find greater drama in the power plays of famous revolutionaries or the inevitable decline of an obsolete class.

This objection is not raised to bemoan how movies about the French Revolution fail to “get it right,” but to highlight the distinct aims of history and fiction, and to underscore their fundamental interdependence. As the very existence of FFFH attests, movies about the past serve an important need. More than just teaching tools, they temporarily free us of the constraints of adequate documentation and scholarly argument to imagine how the past felt. It is a project that enlivens our writing as much as it enlivens our teaching and private conversations. Simultaneously entering into and standing apart from fictions about the past allows us to play with persons and fact and, in so doing, develop a deeper sense of them. Meanwhile, the best of those films foster the empathy of more casual viewers, hopefully enlivening their sense of what was at stake in the French Revolution or the Wars of Religion or the struggle for Algerian independence and suggesting how the past is both different from and like our own time. In the best cases, historical scholarship moves in the other direction, offering texture and scope even to films that dispense with facts we consider important. These are important issues that one might raise in the classroom when teaching a film like Farewell, My Queen, encouraging students to think critically about how a fiction film’s narrative constraints shape its particular account of the past and what we can and cannot learn from that. I, for one, will raise the persistent absence of “the people,” hoping not only to explain and correct for it pedagogically but, perhaps, to plant a seed in the mind of a future film maker.

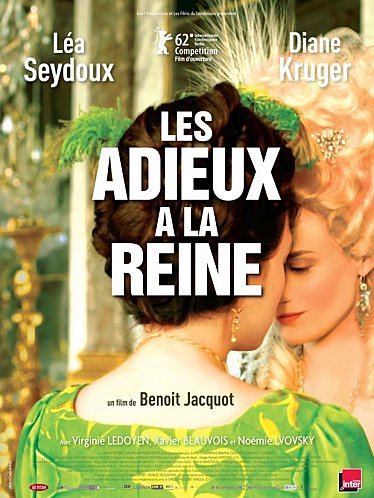

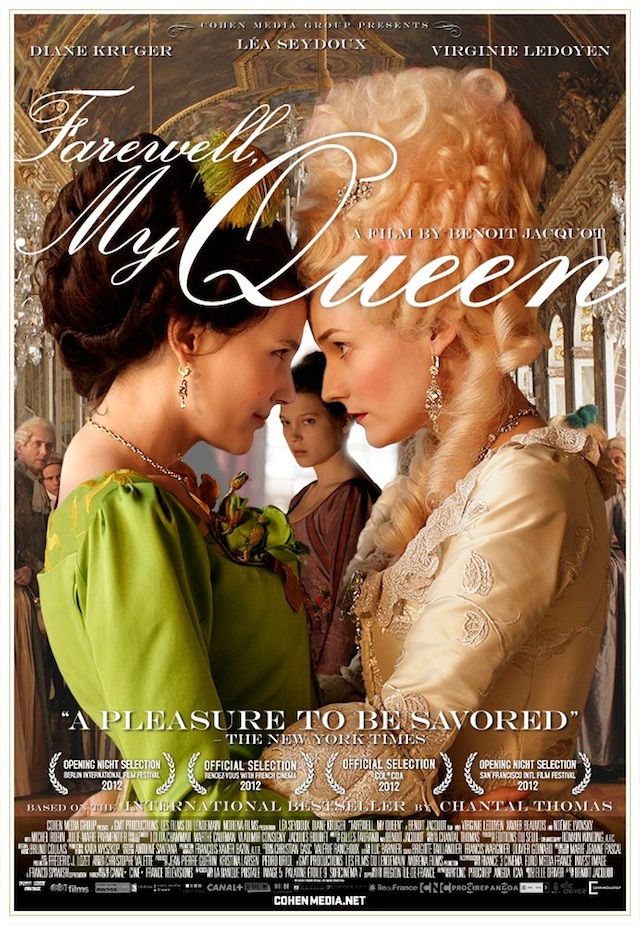

Benoît Jacquot, Director, Les adieux à la reine [Farewell, My Queen] (2012), 100 min., Color, France, Spain, GMT Productions, Les Films du Lendemain, France 3 Cinéma

- Chantal Thomas, Les Adieux à la Reine (Paris: Seuil, 2002), translated by Moishe Black as Farewell, My Queen (New York: Touchstone, 2003).

- W. H. Lewis, The Splendid Century (New York: William Morrow and co, Harper/Collins,1953).

- Simon Schama, Citizens (New York: Vintage,1990) p. 477.

- Jean Renoir’s Popular Front classic, La Marseillaise, stands alone in celebrating the Revolution as a popular achievement. Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade takes the people as its subject but with profound ambivalence, setting its re-enactment of the Revolution in the insane asylum of Charenton.