Liana Vardi

University at Buffalo, SUNY

The proliferation of the French “nonfiction novel” is a phenomenon worth thinking about, especially as we try to protect the realm of fact from the invasion of fake news. The nonfiction novel is really factual reportage. Truman Capote, who invented the term, explained it as “a narrative form that employed all the techniques of fictional art but was nevertheless immaculately factual.”[1] The literary envelope turned an otherwise sordid or trivial event into timeless art. Writers unfamiliar with the art of fiction are unable to achieve this. Quite bizarrely, Capote included novelist Rebecca West amongst them: perhaps because it was crucial that the author remain invisible and not appear in the narrative. It was equally important that the author have lived during (if not witnessed directly) the event and could interview the participants: hence the journalistic component. Capote stated, and others after him, that the moment you use real names, you have to stick to what these people have said. In an interview on “fact and fiction” Emmanuel Carrère suggested that the author had a moral duty to quote precisely, whereas Capote had raised the possibility of libel if he altered words.[2]

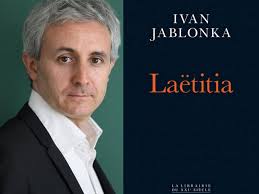

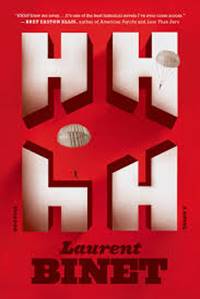

Capote, concerned exclusively with contemporary events, left historical fiction out of the equation yet Laurent Binet makes the very same point about faithfulness in HHhH (2012), the entire novel being a reflection on how far an author can depart from the facts. He very much inserts himself into the book’s narrative, as do Emmanuel Carrère in The Adversary (2000) and Ivan Jablonka in Laëtitia ou la fin des hommes (2016). So what qualifies these books as fiction? This is worth analysing in greater depth especially in the case of Jablonka who is an historian by trade. Historians of France have written novels before. What differentiates this particular one is that it is hard to tell where reportage ends and fiction begins. If it is indeed fiction, then there is misdirection. Jablonka uses the book to argue that the fait divers is a worthwhile object of historical enquiry (chapter 54, “Fait divers, fait démocratique,” 342-50). It offers a window into society. This is hardly original, as the literature on the fait divers demonstrates.[3] Neither is turning from an analysis of the criminal to that of the victim, which is his other stated purpose. Jablonka engages therefore in a double investigation: reassembling the facts about the murder of Laëtitia Perrais in the early hours of 19 January 2011, and digging into the life of the teenager whose life was brutally cut short.[4]

Laëtitia ou la fin des hommes was marketed as fiction. For clues about the way Jablonka structured his story and why he labeled it as fiction, however “real,” one must look at some of his recent work. Ivan Jablonka is a social historian of charitable institutions in nineteenth-century France who teaches at Paris XIII. From his research on abandoned children in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, he moved on to investigate children abandoned during the Holocaust. This touched him personally since his father and his aunt had been left behind in Paris when their parents were arrested in February 1943 and sent to Auschwitz on transport 49. In 2007 he decided, with his father’s enthusiastic help, to find all that could be recovered about his grandparents’ lives. This resulted in the 2012 Histoire des grands-parents que je n’ai pas eus, which garnered three non-fiction prizes. As with Laëtita, Jablonka meant to wrench his subjects from anonymity, and to follow (and contextualize within a broader historical literature) their years in a Polish shtetl, their Communist activism, their flight to Paris, and their death in Auschwitz.

He followed the well-worn format of other searches for relatives’ fate: consulting endless archives, exploring every lead, assembling photographs, speaking to survivors and descendants of survivors, renewing ties with extended family in Argentina, Israel, and the United States.[5] Where there were gaps, he relied on the memoirs of those who experienced a similar fate. For example, in his grandfather’s case, he deduced that he must have been a Sonderkommando in Birkenau. In addition to the horrific ending in the camps, there are equally heart-rending accounts of the misery and fear that were the daily fare of illegal immigrants in Paris’s XXth arrondissement, of the brutal Polish regimes that persecuted Jews and Communists, and of French complicity with the Germans.

As with other works in this genre, each step of the investigation is revealed and detailed, and the findings are questioned and crosschecked until the task is more or less accomplished. The authors know the end, of course, but present the story as a series of unexpected discoveries and false trails to create artificial suspense. Despite this novelistic device, these books are “nonfictions,” as was the case here.

While writing the book on his grandparents, Jablonka found himself questioning the writing of history itself. Soon after the book was published, he produced what he calls its pendant, L’histoire est une littérature contemporaine, manifeste pour les sciences sociales (Seuil, 2014, and in English translation, March 2018).

In its 320 pages Jablonka describes the rise of History in Ancient Greece and its separation from Literature over the longue durée. He examines the practice of each genre since Antiquity, and concludes that it is meretricious to draw a distinction between history/truth and fiction/fake because fiction can be truthful if it adheres to the same project as History’s: to understand the past (or the present). He is careful to distance himself from the “linguistic turn” and the postmodern dismissal of boundaries in writing, because historians remain tasked with explaining the world by means of their disciplinary tools: archival evidence, recourse to existing studies, comparisons, and verification. While they provide answers, the questions they’re asking and their very choice of topic remain too often hidden. The process should become transparent, displaying the scaffolding rather than hiding it. To that end, they should feel free to use the “I” since there is always an I behind the research and the writing.

In its 320 pages Jablonka describes the rise of History in Ancient Greece and its separation from Literature over the longue durée. He examines the practice of each genre since Antiquity, and concludes that it is meretricious to draw a distinction between history/truth and fiction/fake because fiction can be truthful if it adheres to the same project as History’s: to understand the past (or the present). He is careful to distance himself from the “linguistic turn” and the postmodern dismissal of boundaries in writing, because historians remain tasked with explaining the world by means of their disciplinary tools: archival evidence, recourse to existing studies, comparisons, and verification. While they provide answers, the questions they’re asking and their very choice of topic remain too often hidden. The process should become transparent, displaying the scaffolding rather than hiding it. To that end, they should feel free to use the “I” since there is always an I behind the research and the writing.

Through their training, historians fit their findings within a larger framework. They display this to readers through footnotes and bibliographies and Jablonka does not want them to shed this apparatus. He wants them to add another dimension, reviving their ties with literature, sundered in the nineteenth century. Like novelists, they should pay attention to the shaping of a story and its language. Writing being a primary task and not an afterthought, historians and social scientists should invest great effort in their choice of words. Rhetoric would not be amiss. History is a literary art and not a fact-spewing machine, and, whether they realize it or not, historians are already making decisions about the arrangement of their text, even if they do so unthinkingly and formulaically. He thinks a more obvious use of literary techniques can rescue the social sciences from the current lack of interest in what they have to offer. But no matter how he cuts it, his definition of what constitutes “literature” is frustratingly vague. Sometimes it is the freedom to imagine; sometimes it is style or structure.

In my mind, the social sciences get close to literature not through the novel or fiction, but by what I call “writing about the real”: testimonies, in-depth news stories, life stories, autobiographies, travel journals. I reject a definition of literature that stops at novels and fiction. One need only consider masterpieces of literature such as Bayle’s Dictionary and Montaigne’s Essays to see that it means more than fiction. It is in within this framework that one can treat history as contemporary literature.[6] [All translations are mine; the original French versions are located after the Notes.]

This is mixing apples and oranges. Bayle and Montaigne became literature according to a later canon, they were not composed as such, and not all dictionaries or essays are considered classics. He seems to be suggesting, first, that all social sciences become self-reflexive, and second, that they are at their best when they relate contemporary events. Treating literature as a meta-category does not get us any closer to distinguishing between fiction and non-fiction.

There is a certain boldness in demanding that historians produce history as progress reports, although Marc Bloch had already called on historians to point out gaps in their knowledge in The Historian’s Craft, his wartime legacy to the profession. In arguing that there is nothing wrong with vivid imagery and even attributing thoughts to people in the past, Jablonka means for historians to express their personal engagement with their subject rather than hide behind a terse, impersonal tone. He approves of the use of rhetorical devices to reinforce the author’s emotional investment. Jablonka acknowledges that that too strong an engagement might bias the interpretation, but he is confident that he has introduced enough checks and balances to preclude that.

This brings us to Laëtitia ou la fin des hommes where he revisits a fait divers with, he tells us, an historical and sociological eye, and, according to the practice of many nonfiction novelists, he includes himself in the narrative.

The case that drew his attention was the murder of Laëtitia Perrais on the night of 18-19 January 2011 in Pornic in the department of the Loire-Atlantique. She had spent the evening with Tony Meilhon, a drug-addled thief in his early thirties. Despite having a boyfriend she liked and friends she texted constantly, she seemed to be in a reckless mood that day, cheating on her boyfriend with his best friend for a lark and hooking up with Tony. She had been depressed the last few months. After her death, three letters were discovered in which she gave away her belongings, which were taken to be suicide notes. On the afternoon of the 18th, she ran into Tony by chance, at the beach, during her break at the Hôtel de Nantes, where she waited on tables. They went drinking and sniffed some cocaine (something she had not done before). He bought her gloves and picked her up again after her evening shift. They drank in different bars and fooled around in his cousin’s caravan. In the middle of a blow-job (so the forensics would show), she demanded to be driven back to her scooter, threatening to go to the police the next day. Tony dropped her back at the hotel but, in a paroxysm of rage, decided to pursue her (in his stolen car), and knocked her off her scooter 50 meters from her house. He then shoved her inside the trunk, beat her to death, and cut her body into pieces that he tossed in two different ponds. The police found the different limbs months apart. This gruesome murder riveted the nation’s attention all winter.

Figure 1: Laëtitia Parrais

When he grew interested in the case several years later Jablonka revisited every aspect. He read the news reports, watched police video recordings, interviewed participants including Laëtitia’s twin sister Jessica and her friends, visited the sites, and read Laëtitia’s Facebook posts and her innumerable text messages. Although he admits to some failings, Jablonka denies any prurience, claiming that his main motivation was to restore the dignity Laëtitia lost through her terrible death.

I received Jessica and her relatives’ informed consent; I did everything I could to respect their words, their dignity, their sorrow; I used pseudonyms for several; I left out hatreds and invectives; I was the person who listened before he wrote. But I can’t exclude the possibility that I intruded and was clumsy. It is not easy to escape such flaws when one is conducting an investigation. (336-37)

Figure 2: Kevin (Laëtitia’s boyfriend), Jessica, and Orianne, the Patron’s daughter. 27 January 2011, Maxppp/Presse Océan

To establish a rapport with the professionals involved, Jablonka drew parallels between the historian-as-detective and professional investigators, policemen, magistrates and journalists, all equally engaged in a search for the truth. He thus stretched a fraternal hand to professionals who work from different premises. He convinced enough of his interlocutors to grant him access to all documents related to the case. As he himself explained, sharing a common ethos created a bond, and he developed friendships with several of them. On the other hand, he found he had little to say to the youths he interviewed, although he believed they had a silent understanding. Yet he cannot suppress his contempt for their working-class culture. He has this to say about Laëtitia:

Despite her shopgirl’s romanticism, her total uninterest in politics, and her absolute indifference to the broader culture and life of her society, this spiritual void did not impede the existence of a conscience that vibrated on its own. (191)

Laëtitia’s murder became an affaire d’état once Nicolas Sarkozy, who misunderstood the nature of the case, publicly chastised the Nantes magistrates for letting a known rapist out into the streets. They went on strike. For a brief moment, the strike spread nationally. The perpetrator was not a repeat sex offender, however, but a small-time drug dealer with a violent streak and a prison record. There was no sign that he had raped Laëtitia. He hated sex offenders and had raped a fellow inmate with a stick to demonstrate his distaste. If he posed a threat, psychologists concluded, it lay in the future, as he seemed a woman-hating serial killer in the making.

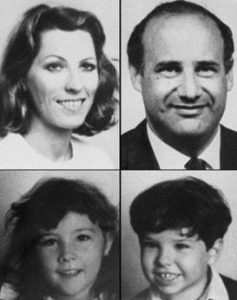

Figure 3: www.parismatch.com, Laëtitia disparition-14756

The book revisits each step of the investigation from the discovery of the girl’s abandoned scooter to a final, tense, blow-by-blow description of her last night. In parallel chapters, Jablonka reconstructs Laëtitia’s and Jessica’s childhood, the domestic violence that sent their mother to an institution, their father’s pathetic efforts to redeem himself, the intervention of social services, the girls’ relegation to foster homes, and how they landed at last with the Patrons, a middle-class family living in Pornic-La Bernerie, a seaside resort not far from Nantes. Unfortunately, the paterfamilias, Gilles Patron, abused Jessica sexually for years as well as other girls in his care, although it is not clear whether or not he laid a hand on Laëtitia (see below).

Figure 4 Gilles Patron and 5: Franck Perrais and his daughter Jessica

In the parts on the twins’ upbringing, Jablonka weighs in with sociological analysis. His quest for Laëtitia’s “sunnier moments” suffers as a consequence. The lives of the sisters – like those of the nineteenth-century foundlings in his academic research – are approached through their suffering.

I acquired a technical language and learned expressions, but I would like instead to recover the murkiness, the vagueness, the tendency to forget, the feeling of helplessnes and incomprehension that exist in a child’s mind, Laëtitia’s, Jessica’s, or of the little child we once were. (47)

This princess deserves a Little Prince in which the solemnity of adults would be excluded:

Daddy beats mommy/ Mommy cries/ They put daddy in the clink/ It’s my fault/ I don’t want to go to jail/ Mommy left/ Will mommy and daddy come back?

Recalling that Jessica remembered the beatings, he adds: “Je n’invente qu’à moitié.” (48) He does not say what half he has invented. Should we consider his statement a page later to be fiction or sociological observation?

The twins learned that when she cries from pain or from distress, mommy just obeys her nature. All those traumas have, so to speak, prepared the terrain. It is in this sense that one can speak of destiny, of lives programmed for violence and submission. (49)

All this is speculation that he ties to a physiology of poverty. As he presents it, the Perrais twins are products of the Nantes underclass, huddled in their HLM (when they are so lucky –the girls live on the street for a while with their father), struggling with unemployment, alcoholism, abuse, violence, prison, learning disabilities, and general dysfunctionality. Extended family does its best, but everyone is trapped, or so it would appear. At cause is a brutal misogynistic society (the title’s “end of men”). Men rule, sometimes with their fists, and women tremble and obey. Thus, in her killer’s eyes, Laëtitia had to die because she dared to defy him.

Every description accentuates poverty and deprivation. At the Patrons’, the girls’ rooms are bare; Jessica’s jewelry is pathetic; her slim photo album also. Jablonka has taken more pictures of his own daughters in one month. The good times get short shrift such as the vacations that the Patrons took them on. Jablonka instead plays up their vocational training, Laëtita’s as a waitress and Jessica’s as a cafeteria cook, as part of their CAP cuisine at the local lycée. Jablonka treat this as their means of escape, their key to a better future than their parents’. Given their background, however, this is the only future possible for these girls, neither one of whom is dim. Jablonska may share all he can find about Laëtitia’s brief life, but I wouldn’t call it a celebration.

Figure 6: Paris-Match 27 August 2011: la double peine de Jessica Perrais 154057/DR

In France, 160,000 children currently live in foster centers, and while Jablonka cites the laws that allow social services to intervene, he also details how Laëtitia and Jessica were sucked into a constricting Foucauldian system of surveillance, however well intentioned.[7] To compensate for this dreary perspective, Jablonka does not shy away from hyperbole. Speaking of Jessica sitting with him in a cafeteria:

If they knew that this innocuous young woman hid a heroine of our times whose moral strength can serve as a model in moments of small or great distress, the entire refectory would fall on its knees. (332)

And then there is that unfortunate chapter heading: “Laëtitia, c’est moi.” (357)

In what is to me his most disturbing intrusion, Jablonka believes he can pierce Laëtitia’s psychology. For example, how she felt about Tony, providing no proof but a vague reference to the helping professions:

On Laëtita’s side, there is attraction, but it is a generous affection, a feeling of compassion for this man whom life has battered; she feels disgust the moment he demands sex. (312)

He goes so far as to discern a “nursing” complex in her that he ties to her antecedents:

Her “abandonic” past, as psychologists call it, determined the nature of her relations to others – that other that one must seduce, retain, interest, so that he doesn’t abandon you. (316)

Why does Jablonka allow himself such liberties? Nothing in the evidence provided by Laëtitia’s cell-phone texts to her friends supports this. At Meilhon’s appeal in October 2015, as the press and Jablonka report, Jessica stated she did not think that Tony Meilhon had seduced her sister, but he might have influenced her by something he said. Like herself, her sister was trusting and too easily influenced.[8] And Jablonka has to admit another possibility: going with Tony may just have been commonplace adolescent risk-taking. But, he adds, most turn back from the abyss, recall that they are loved, and go back home. Laëtitia had no such internal brakes. “Putting herself in danger voluntarily between five o’clock and midnight has a tragic resonance that is the echo of her childhood.” (319) He cannot go on too long in this vein because the evidence shows that “[I]n the end, Laëtitia said no. No to Meilhon. No to authority and cocaine. No to decisions made for you. No to threats, to harrassment, to beatings, to unwanted sex. She demanded that he take her back to La Bernerie.” (319) “She died a free woman.” (320) He is far from repentant about his psychologizing:

To understand Laëtitia’s torment and because her voice has been extinguished forever, it is necessary to turn to educated fictions [fictions de méthode], that is to hypotheses that can, by their imaginary character, penetrate the secret of a soul and establish the veracity of facts. (253)

He therefore outlines three possible scenarios for Laëtitia’s suicidal urges. It comes down, he believes, to her disappointment that the Patron family had not proven a haven for her and her sister. She had looked for the comfort of a loving family, and had discovered another series of deception. (258) By 2013 Patron had finally been charged with the sexual abuse of minors. Jablonka asked Patron’s lawyer and the judge at his trial, whether they thought that Patron had sexually abused Laëtitia. As far as the judge was concerned, Patron might have done so, but for magistrates, the truth resides in what the law considers objective evidence. Beyond this the truth remains “forever inaccessible.” (256) Jablonka agrees with the judges that the truth is inaccessible and that Patron should be given the benefit of the doubt. But he stubbornly returns to childhood trauma as the guiding force.

Actually, the question is irrelevant. Because it was enough for Laëtitia to have grasped the nature of the relationship between Patron and Jessica for her life to be turned upside down, for her to feel, like she had when she was three, suspended in the air [her father had held her by her feet over a banister], to understand that lies had soiled everything, that violence was ever-present… (257)

Jessica freaked out after learning from her uncle, at Laëtitia’s funeral, about her family’s history of domestic abuse, which Jablonka had earlier stated she remembered on her own, and all she wished was to be adopted by the Patrons. They refused, despite her frantic pleas. Like her sister, Jablonka surmises, she had looked for love and had accepted it came at a price. Despite this, her foster family rejected her. It would seem that Jablonka is projecting Jessica’s delusions onto Laëtita.

Figure 7: Jessica being comforted by Patron at her sister’s funeral

His “literary” touch (and his imagination), his socio-psychological and historical investigation, forge a narrative where the past determines the present. (347)

Yet he muddies the waters again when he returns to the fait divers, and how he means to push it beyond “its mythological resonances and fatalism,” and regard it instead as a microcosm of larger societal forces. But the narrative thread he has chosen keeps returning to the childhood trauma.

As a conclusion, he reflects: “As a novelist ten years ago, I wrote non-truth; at the same time, as a doctoral candidate, I non-wrote the truth. Today, I would like to write the truth. This is the gift Laëtitia has left me.” (349) Citing Patrick Modiano’s speech at the Nobel Prize ceremony in 2014: “…C’est le rôle du poète et du romancier aussi de dévoiler ce mystère et cette phosphorescence qui se trouve au fond de chaque personne.”[9] He adds: “this is also the role of the historian sociologist.” (357) In my mind this is stretching the role of the historian to its breaking point. So why the genre ploy? Rather than proudly acknowledging this work as an example of the new way to write history, he let it be marketed as a novel. It took seven rounds of voting for Laëtitia to win the Médicis prize for fiction. I can understand why. Its ambiguous status would give anyone pause. [10]

***********

Jablonka’s intervenes in his “novel” with socio-historical and psychological analyses. Recent French nonfiction novelists adopt the opposite posture. The work is fiction because of the role they play in it. L’Adversaire by Emmanuel Carrère is considered a model of the French nonfiction novel based on a fait divers, and it also inspired two films. Nicole Garcia’s L’Adversaire (2002) sticks very closely to Carrère’s narrative, but changes the names. Laurent Cantet’s Time Out (L’emploi du temps, 2001) is more loosely based on the events that Carrère relates and delves into the psychology of a man who has been fired from his job and pretends he hasn’t. It isn’t gory, unlike the events of 1993.

On the 9th and 10th of January 1993, Jean-Claude Romand murdered his wife, his two small children, his parents, and their dog, in their homes in the Jura, then drove to Paris to kill his mistress, who beat him off and was able to escape. Determined to end it all, Romand returned home, set his house on fire, and took an overdose of pills, but survived. The case became a national sensation once it was revealed that Romand had lived his life as a prime imposter. Unable to face exams, he had failed his first year at medical school and for years re-registered in year two, eventually claiming that he had been certified as a neuro-surgeon and was teaching at a university, conveniently far away from home. He then pretended to work for the World Health Organization across the border in Geneva.

He actually made a living by conning his relatives and friends into giving him their savings, telling them that he had insider knowledge through his Genevan contacts and could get them higher rates of return by opening secret accounts for them. The scam continued for years, mainly because none of the victims needed the money immediately. However, once he ran out of close relations (and quite likely killing his father-in-law, who was getting too inquisitive), Romand set his sights on acquaintances seeking short-term investments, including his mistress. As pressure began to mount for him to produce the interest and then refund the capital, he “ran out of options,” and butchered those closest to him.

He actually made a living by conning his relatives and friends into giving him their savings, telling them that he had insider knowledge through his Genevan contacts and could get them higher rates of return by opening secret accounts for them. The scam continued for years, mainly because none of the victims needed the money immediately. However, once he ran out of close relations (and quite likely killing his father-in-law, who was getting too inquisitive), Romand set his sights on acquaintances seeking short-term investments, including his mistress. As pressure began to mount for him to produce the interest and then refund the capital, he “ran out of options,” and butchered those closest to him.

Carrère, who attended the trial, sought to understand why Romand chose to do nothing with his life and why he turned to violence as the only way out. He initiated contact with the killer, who had meanwhile metamorphosed in jail into a repentant Christian. Romand acknowledged his culpability, but treated his actions as his path to God. It was still all about him.

The façade that Romand had established of a good family man, helpful neighbour, and upstanding citizen, Carrère attributes to his tough upbringing and the passivity required to survive his authoritarian father. He learned from childhood to dissimulate so that pretending became a way of life. Intrigued by how he whiled the hours while he was “away,” Carrère establishes a parallel between the writer who idles away time while his fictions build inside him to Romand’s days spent in hotel rooms or walking the Jura hills. In the end, however, the man turns out to be, disappointingly, utterly uninteresting.

When Carrère wrote the novel, he was struggling with religious issues, the existence of evil in particular: the adversary of the title is the devil.[11] He wonders what in him has drawn him to this monster, so that the fait divers becomes a vehicle for self-questioning as well as confrontation with the Other. The writing took a long time. Carrère had difficulty finding the right tone. He tried changing perspectives, writing from the vantage-point of Romand’s friend Luc, but that didn’t sound right either. Over five years, he wrote different versions, abandoned the project, and then picked it up again once he realized that he had to insert himself into the story.[12] He would use the case to investigate himself. This was to be his last novel. Since then he has been writing biographies and other non-fiction works, but always retaining the personal angle.

When Carrère wrote the novel, he was struggling with religious issues, the existence of evil in particular: the adversary of the title is the devil.[11] He wonders what in him has drawn him to this monster, so that the fait divers becomes a vehicle for self-questioning as well as confrontation with the Other. The writing took a long time. Carrère had difficulty finding the right tone. He tried changing perspectives, writing from the vantage-point of Romand’s friend Luc, but that didn’t sound right either. Over five years, he wrote different versions, abandoned the project, and then picked it up again once he realized that he had to insert himself into the story.[12] He would use the case to investigate himself. This was to be his last novel. Since then he has been writing biographies and other non-fiction works, but always retaining the personal angle.

While the fait divers has long been an inspiration to novelists, Laurent Binet tackles the problematic encounter of history with fiction in historical novels. In HHhH, whether as gimmick or sincere questioning, he comments repeatedly on the limits that real events place on the author who attempts to fictionalize them. How much can a writer invent, given the weight of available facts, and the lack of evidence about the inner thoughts and mental state of the people involved? He hesitates each time he projects a thought or a dialogue onto one of his subjects, and shares his reticence with the reader. In effect, the real dialogue in the book is between the author and himself about what he can and cannot write. This technique forces the reader to detach from the story and to contemplate, along with Binet, how we approach the past.

HHhH (standing for the German joke “Heydrich is Himmler’s brain”) recounts the assassination in the Czech capital on 27 May 1942 of the “Butcher of Prague” and mastermind of the Final Solution, SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich. Operation Anthropoid was conceived in London to show that, despite the takeover of Czechoslovakia by the Germans, national resistance and the hope for reunification were not dead. The Sudetenland, Bohemia, and Moravia had been absorbed into the Reich; Slovakia had set up a separate government that collaborated with the Nazis. The two men parachuted into Heydrich’s Protectorate to assassinate him were deliberately chosen to represent the indivisible union of the two principal nationalities. Josef Gabčik was a Slovak and Jan Kubis,̌ a Moravian. Both were Czech patriots who had fled their country for Poland in 1938, fought there in 1939, and finally escaped to France where they joined the Foreign Legion. They saw action in spring 1940 and, after the debacle, like several thousand other Czech soldiers, ended up in Britain. There they trained in Scotland for special missions. They were meticulous, professional, and aware that theirs was a suicide mission. Gabčik was more outgoing than Kubiš but both were friendly and well liked. They had girlfriends in England and found others in Prague. It is unclear whether they had met before coming to England, but they got along famously.

Figure 8: Jan Kubiš and Josef Gabčik.

The plane that carried them above the Czech countryside on 28 December 1941 included other men with different missions. They would all meet again in Prague. When the assassination plans seemed stalled, the SOE parachuted two other Czechs to push the mission forward, one of whom would betray them to the Germans during the manhunt in June 1942.

Half of Binet’s book deals with Heydrich’s rise in the Nazi hierarchy, his commitment to the “purification” of the Reich, and his plans for the annihilation of 11 million Jews. Heydrich, it was rumoured, had Jewish ancestors, but Binet does not indulge in psychological guesswork about the effect this may have had on him, focusing instead on Heydrich’s career. Discharged from the navy in 1929 after being charged with rape – an accusation that his well-connected fiancée managed to have quashed — helped by his “Aryan” looks, pushed by his ambitious wife who was already a member of the Nazi Party, the former lieutenant refashioned himself as a dedicated Nazi. Put in charge of a nascent Gestapo surveillance unit, Heydrich turned it into a highly efficient department amassing information on dignitaries who visited the brothel he set up in Berlin. He became invaluable to Himmler (as well as a potential rival) and had the confidence of the Führer. He was a natural to oversee the elimination of the Jews and other enemies of the Reich. While working out the details of mass annihilation that he would present at Wansee on 20 January 1942, he was acting-governor of Bohemia and Moravia, sent there to repress all resistance activities. While enjoying the high life that came with his new position, he ruled his protectorate ruthlessly, spreading terror throughout Prague and the countryside. Rumours were rife that he was about to be transferred to Paris, so, with no time to lose, the paratroopers had to act quickly. Heydrich’s movements and routines had been meticulously tracked during weeks of preparation, and a location had emerged as the least unsuitable for an attack, along a twisty road where his car would have to slow down.

Since their arrival, Gabčik and Kubiš had managed to gain the support of what remained of the Czech resistance. They were hidden by local families and their new girlfriends. Perhaps, Binet speculates, they even allowed themselves to imagine that they might survive. On the morning of 27 May, they attacked Heydrich’s convertible black Mercedes as it wound its way to Prague Castle. Gabčik’s Sten gun jammed as he stood in front of the car, in full view of Heydrich and his driver. Acting quickly, Kubiš threw a grenade that blew up the back of the car. Fragments hit their main target, but Heydrich nonetheless staggered out of the vehicle, chasing Kubiš while his driver chased Gabčik. Both men managed to escape, convinced that they had failed. But Heydrich had been wounded and collapsed in the street. He was rushed to hospital and on 4 June succumbed to septicemia caused by horse fibers from the car’s upholstery that had penetrated his wounds. The Germans launched a manhunt in earnest, and hundreds of soldiers searched apartment block after apartment block. The Czech resistance hid seven parachutists in the crypt of an Orthodox church. They were denounced. It is there, after a six-hour battle with 800 German troops, that they succumbed on 18 June. The reprisals were horrific. The village of Lidice, suspected of harbouring partisans, was razed to the ground and all its inhabitants murdered.

These are dramatic events in and of themselves, as Binet makes plain. Why invent when there is such rich material? It is not that Binet doesn’t allow himself to speculate throughout about what the participants might have felt or thought, but he then chides himself and retracts any assertion he cannot prove. Despite presenting his book as fiction, he cannot break his implicit “contract” with the reader to report only the truth.

The recent films Anthropoid (2016) and HHhH (2017), both of which tell the story of Heydrich’s assassination, are not bound by any such commitment and take liberties with the “real story.” Anthropoid leaves Heydrich out entirely, except for a minute onscreen as he is hit by the blast in his car, to focus entirely on Gabčik and Kubiš, reinvented to differentiate them, as if the story itself were not remarkable enough. Rather than the professional, matter-of-fact and happy-go-lucky soldiers described by Binet, presumably based on witness accounts (and on this score, the film HHhH is more accurate), Anthropoid shows them as tense and ill-informed, partly so that other characters can fill them in on the situation in Heydrich’s Protectorate. Gabčik, played by Cillian Murphy, is a bundle of nerves throughout, yet the clear leader of the two. Jamie Dornan’s Kubiš is a more retiring figure who “does not want to die” and whose hands tremble when he holds a gun, but he rallies each time since History cannot be denied. Everyone speaks in what we must suppose to be a Czech accent, which is irritating.

The film HHhH (distributed in English as The Man With the Iron Heart) spends a long time on Heydrich’s career. Jason Clarke is miscast in the title role, more tormented than the psycho-sadist he ought to be portraying. His resemblance to Ted Cruz annoyed me throughout. Moreover, although Operation Anthropoid eventually gets underway, the real dramatic tension in the movie lies not with the plot to kill Heydrich but within the Heydrich menage, as a distraught Lina Heydrich (Rosamund Pike) realizes that her husband likes his job more than her and pines tearfully for him. History tells us that Lina was a harpy who thrived in Prague. Operation Anthropoid gets less screen time, requiring shortcuts and pure invention, the very thing that Binet warns us against.

In the end, Anthropoid’s great virtue lies in its dramatic recreation both of the assassination and of the final resistance of the seven parachutists in the Karel Boromějský Greek Orthodox church, a thrilling action-packed finale. Kubiš succumbs to his wounds but Gobčik and several others commit suicide rather than surrender to the Germans. This outcome is expedited in HHhH, where in the end only Gobčik and Kubiš survive and shoot each other as the water with which the Germans have flooded the crypt envelops them.

At first sight, the nonfiction novel seems to be an oxymoron. Nonetheless it has been invading our fictional space, blurring the line between fact and fiction. This may be a passing phase. Emmanuel Carrère abandoned writing novels after L’Adversaire, and turned to biography that still includes references to his own life. Laurent Binet’s new novel, La septième fonction du langage (Paris: Grasset, 2015) is a fanciful investigation of the “murder” of Roland Barthes, even if the characters are real. There are also fake nonfiction novels. My favorite is Delphine de Vigan’s D’après une histoire vraie (2015, in English, Based on a True Story, 2017). So we shouldn’t be taken in by the semblance of veracity, unless all the facts are verifiable, Google to the rescue. More worrisome is when historians cannot make up their minds about what they are writing: reportage? fiction? Ivan Jablonka claims that history should be written in a new way with historians frankly admitting what they know and don’t know. They must still use their disciplinary tools to get at the past, but might intervene more openly in the text and use their imagination. Imagination, as I understand him to say, is not quite intuition but rather educated hypotheses. So what makes Laëtitia ou la fin des hommes fiction rather than his new kind of history? What did he turn it into fiction? I have tried to guess but I might be totally wrong. Maybe reading into people’s souls is not the problem.[13] Then if not that, what? It is well written but not a “literary” masterpiece. Maybe Jablonka tossed a coin. We are faced with a quandary: piles of his book can be found both in the fiction and social history sections of the French bookstore Gibert Joseph. That is not his doing, of course, but when fictional modes become interchangeable with historical writing, historians should get worried.

Ivan Jablonka, Laëtitia ou la fin des hommes, Paris: Seuil, 2016

Ivan Jablonka, L’histoire est une littérature contemporaine, manifeste pour les sciences sociales, Paris: Seuil, 2014 (English version 2018)

Ivan Jablonka, Histoire des grands-parents que je n’ai pas eus, Paris: Seuil 2012 (English version 2016)

Laurent Binet, HHhH, Paris: Grasset, 2009 (English version 2012)

Emmanuel Carrère, L’Adversaire, Paris: P.O.L, 2000 (English version 2001)

NOTES

[1] See George Plimpton’s interview of Truman Capote in “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel,” New York Times Book Section, 16 January 1966. http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/capote-interview.html; also Geoff Dyer, “’Based on a True Story’: the Fine Line Between Fact and Fiction,” The Observer, 6 December 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/dec/06/based-on-a-true-story–geoff-dyer-fine-line-between-fact-and-fiction-nonfiction

The French also refer to Roland Barthes, “Structure du fait divers” in Essais critiques (1964), Oeuvres complètes, volume II, Paris: Seuil, 2002, pp.442-51.

[2] Emmanuel Carrère on fiction and non-fiction (11 January 2010) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SHl2FOvE3gA

[3] The honourable history of the fait divers’ influence on French literature from the eighteenth century to the present day is described by Minh Tran Huy in Les écrivains et le fait divers, une autre histoire de la littérature, Paris: Flammarion, 2017.

[4] See his interview in http://www.lefigaro.fr/livres/2016/11/02/03005-20161102ARTFIG00156-ivan-jablonka-l-histoire-d-un-extraordinaire-prix-medicis.php

[5] See for example Daniel Mendelsohn, The Lost: A Search for Six of the Six Million. New York: Harper Collins, 2006. Philippe Sands, East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2016, and Hisham Matar, The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between. New York: Viking Press, 2016. For an excellent commentary on the genre, see the review of The Lost: http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/books/2006/09/the_triumph_of_the_real.html

[6] http://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2014/10/02/paul-veyne-et-ivan-jablonka-l-histoire-peut-s-ecrire-pleinement_4499430_3260.html The Nobel prize for literature was awarded only three times for “nonfiction” writing: to Bertrand Russell, Winston Churchill, and Elias Canetti. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/themes/literature/espmark/

[7] France2, journal de 20 heures, 2 July 2017, http://www.francetvinfo.fr/replay-jt/france-2/20-heures/immersion-une-enfance-entre-parentheses_2265883.html.

[9] His definition of “ficitions de méthode” and his prescriptions for a new approach to the social sciences, are summarized in: http://blogs.histoireglobale.com/quand-les-fictions-deviennent-methode-rencontre-avec-ivan-jablonka_4102

[10] The official Nobel prize English translation states this as follows, pp.12-13: “It is the role of the poet and the novelist, and also the painter, to reveal the mystery and the glow-in-the-dark quality which exist in the depths of every individual.”

[11] See Christophe Reig, Alain Remestaing, and Alain Schaffner, eds., Emmanuel Carrère, Le point de vue de l’adversaire. Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2016.

[12] Emmanuel Carrère on L’Adversaire (11 January 2010) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yVqY9PXJs-k.

[13] While Libération shares my interpretation of the fictional aspects, unlike me, it celebrates the hybrid. http://next.liberation.fr/livres/2016/11/02/en-primant-laetitia-d-ivan-jablonka-le-jury-du-medicis-celebre-l-hybridation-des-genres_1525711

source for Jablonka’s grandparents photograph: https://crehist.hypotheses.org/1011

QUOTATIONS FROM LAËTITIA IN THE ORIGINAL FRENCH, in the order in which they appear.

[a] A mes yeux, les sciences sociales se rapprochent de la littérature non par le roman, mais par ce que j’appelle les « écrits du réel » : témoignages, grands reportages, récits de vie, autobiographies, carnets de bord. Je m’inscris en faux contre une définition de la littérature qui se résume soit au roman, soit à la fiction. Il suffit de prendre de grands chefs-d’œuvre de la littérature, comme le Dictionnaire de Pierre Bayle ou les Essais de Montaigne, pour voir que ce n’est pas de la fiction. C’est dans ce cadre-là qu’on peut dire que l’histoire est une littérature contemporaine.

[b] J’ai reçu le consentement éclairé de Jessica et de ses proches; j’ai tout fait pour respecter leur parole, leur dignité, leur peine; j’ai remplacé certains noms par des pseudonymes; j’ai passé sous silence des haines, des invectives; avant d’écrire, j’ai été celui qui écoute. Mais je ne peux pas exclure d’avoir été moi-même intrusif et maladroit. Il n’est pas facile d’échapper à ces travers quand on mène une enquête. (336-7)

[c] Si son romantisme de midinette se conjuguait à un apolitisme total, une indifférence absolue à la culture et à la vie de la cité, ce néant spirituel n’empêchait pas une conscience vibrante d’elle-même. (191)

[d] J’ai appris des termes techniques, des expressions savantes, mais j’aimerais au contraire retrouver le flou, le vague, la propension à l’oubli, le sentiment d’impuissance et d’incompréhension qu’il y a dans l’esprit d’un enfant, Laëtitia, Jessica, ou le tout-petit que nous fûmes.(47)

[e] Pour cette princesse, il faudrait écrire un Petit Prince où la gravité et le sérieux des adultes n’auraient pas droit de cité.

Papa tape maman/ Maman pleure/ On a mis papa au coin/ C’est ma faute/ Je ne veux pas aller en prison/ Maman est partie/ Est-ce que papa et maman vont revenir? [48]

[f] Pour les jumelles, l’idée s’est imposée que, quand elle crie de douleur ou pleure de détresse, maman ne fait qu’obéir à sa nature. Tous ces traumatismes ont, pour ainsi dire, préparé le terrain. C’est en ce sens qu’on peut parler de destin, de vies programmées pour la violence et la soumission. (49)

[g] S’ils savaient que dans cette jeune fille anodine se dissimule une héroïne de notre temps, dont la force morale peut servir de modèle dans les petits et grands malheurs de l’existence, c’est tout le réfectoire qui se mettrait à genoux. (332)

[h] De la part de Laëtitia, il y a de l’attirance, mais c’est une affection généreuse, un sentiment de compassion pour ce grand cabossé de la vie; elle éprouve du dégoût dès qu’il réclame du sexe. (312)

Son passé “abandonnique” comme disent les psychologues, a determiné la nature de son lien à autrui –autrui qu’il est nécessaire de séduire, de retenir, d’intéresser, pour qu’il ne vous abandonne pas. (316)

[i] Sa mise en danger volontaire de 17 heures à minuit, a une résonnance tragique qui est l’écho de son enfance. (319)

[j] À la fin Laëtitia a dit non. Non à Meilhon. Non à l’autorité, non à la cocaïne. Non aux décisions qu’on prend à votre place. Non aux menaces, au harcèlement, aux coups, aux relations sexuelles forcées. Elle a exigé qu’il la ramène à La Bernerie. (319) Elle est morte en femme libre. (320)

[k] Pour comprendre le tourment de Laëtitia, et parce que sa voix s’est éteinte à jamais, il est nécessaire de recourir à des fictions de méthode, c’est-à-dire à des hypothèses capables, par leur caractère imaginaire, de pénétrer le secret d’une âme et d’établir la vérité des faits. (253)

[l] Pour comprendre le tourment de Laëtitia, et parce que sa voix s’est éteinte à jamais, il est nécessaire de recourir à des fictions de méthode, c’est-à-dire à des hypothèses capables, par leur caractère imaginaire, de pénétrer le secret d’une âme et d’établir la vérité des faits. (253)

[m] Mais au fond, la question n’a pas vraiment d’importance. Car il a suffi que Laetitia saisisse la nature de la relation entre M. Patron et Jessica pour que la vie bascule, pour qu’elle se sente, comme à trois ans, suspendue dans le vide, pour qu’elle comprenne que le mensonge avait tout gangrené, que la violence était toujours là…(257)

[n] Romancier il y a dix ans, j’ai écrit du non-vrai; thésard à la même époque, j’ai non-écrit du vrai. Aujourd’hui, je voudrais écrire du vrai. Voilà le cadeau que Laëtitia m’a offert. (349)