Issue 4

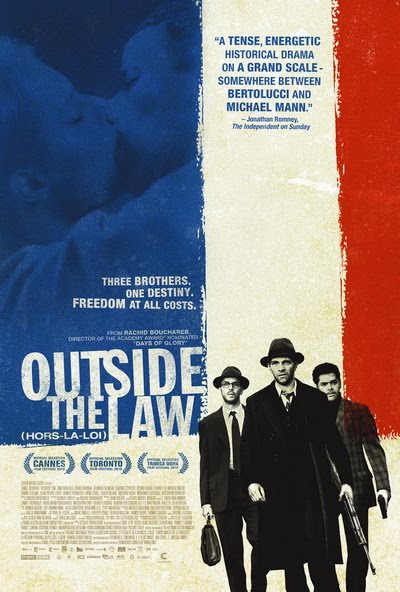

Hors la loi (2010) is one of a number of recent French films dealing with the Algerian War. Mon colonel (2006, Laurent Herbier, director) revisits the use of torture through the eyes of a traumatized French lieutenant. Despite being shot in Algeria, the film focuses on the French experience. The TV drama Nuit noire [English version: October 17, 1961] (2005, Alain Tasma, director) depicts the events leading up to the infamous massacre of demonstrators in Paris in 1961 from multiple perspectives: that of the policemen (all the way from the hapless victim of reprisals to Prefect of Police Maurice Papon who organizes the repression), members of the FLN (who are divided on tactics), French supporters of the Algerian cause, and innocent bystanders caught in events. Set mainly in the 18th arrondissement, it offers glimpses of the Nanterre bidonville. Outside the Law takes us even further into the heart of the bidonville. The movie’s parti pris is to present events from the perspective of Arab Algerians eking a miserable living in France and to account for their increasing militancy. Whether the rendition is accurate or not, an issue our reviewer addresses, the film gives us new ways of discussing the war, exile, and terrorism with our students.

Hors-la-loi/Outside the Law

Todd Shepard

Johns Hopkins University

Outside the Law deploys the filmic language and narrative conventions of two popular cinematic genres –historical epic and gangster film – to drive a sweeping narrative that begins and ends in Algeria, stops briefly in Vietnam, Germany, and Switzerland, but takes place primarily in France. It is north of the Mediterranean that this story about a family of Algerians grapples most intensely with the questions of violence, the law, justice, and the relationship between French and Algerians. The French state and its accomplices first forced all of these questions upon them in North Africa, expelling the family from their ancestral farm in 1925, killing father and daughters in Sétif on May 8, 1945, calling one son, Messaoud, into the army (he is captured by North Vietnamese troops at Dien Bien Phu) and placing the second, Abdelkader, in a Paris prison for his nationalist activism. It is to be near him that the third son, Saïd, convinces their mother – who, like the two daughters, has no name – to leave Sétif behind. They settle in the bidonville of Nanterre. It is 1955.

The story that follows ends inside the Porte de Lilas metro station, when Saïd and Abdelkader are both dragged by police officers off the wagon. Abdelkader is a leader of the Parisian Front de Libération National (FLN); Saïd has risen through the Parisian pègre to run both a cabaret (“La Casbah”) and a boxing club. Abdelkader forces Saïd to cancel the prize-fight he has dreamt of holding between his boxer (“the Algiers Kid”) and the current champion of France. The only fight that matters that night, however, is between the French state and the Algerian population of the département of the Seine. It is October 17, 1961. On the quai, Abdelkader summons the crowds of Algerians, men and women who cower as police billyclubs rain down on them, to take up the chant: “Independence Now!” With one shot, a policeman kills Abdelkader. Saïd looks on. The screen fades to sepia as documentary images of crowds celebrating Algerian independence in July 1962 (with the green, white, and red crescent flag colored in) frame the credits.

The story that follows ends inside the Porte de Lilas metro station, when Saïd and Abdelkader are both dragged by police officers off the wagon. Abdelkader is a leader of the Parisian Front de Libération National (FLN); Saïd has risen through the Parisian pègre to run both a cabaret (“La Casbah”) and a boxing club. Abdelkader forces Saïd to cancel the prize-fight he has dreamt of holding between his boxer (“the Algiers Kid”) and the current champion of France. The only fight that matters that night, however, is between the French state and the Algerian population of the département of the Seine. It is October 17, 1961. On the quai, Abdelkader summons the crowds of Algerians, men and women who cower as police billyclubs rain down on them, to take up the chant: “Independence Now!” With one shot, a policeman kills Abdelkader. Saïd looks on. The screen fades to sepia as documentary images of crowds celebrating Algerian independence in July 1962 (with the green, white, and red crescent flag colored in) frame the credits.

To tell this story of the Algerian Revolution, director Rachid Bouchareb relies on archetypes – of the mother, the land, the fraternal ties that bind, and the blood that always chases blood – to anchor the film’s architecture. His insistent use of citations does similar work, notably of well-known scenes from Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (for example, of the condemned nationalist taken from his cell and guillotined, while other Algerian prisoners look on and chant) and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, I and II (for example, Saïd’s execution of the Muslim notable, or caïd, who had carried out the French order that drove the family from their land), but many others, too (such as the replay of a scene when Alain Delon and his men were in North Vietnamese custody in the thriller The Centurions). One family – one mother and three sons – caught up in history, which reads as tragedy.

Messaoud and Abdelkader die struggling for Algeria’s independence; Saïd just wants to succeed. Still, he expects that, when he does – when his “Algiers’ Kid” becomes champion of France when “La Casbah” becomes the jewel of Paris night life – the French will be forced to recognize what Algerians can do. The exchange between Abdelkader and Saïd as the Kid warms up for the fight that will not take place in Paris, on October 17, 1961 is telling. Saïd: “Imagine it, an Algerian champion of France! It will be a great day.” Abdelkader: “No, that will be when an Algerian is Algerian champion. Your boxer isn’t French. He must fight for Algeria.” What is telling, at least for the historian, is that this scene – and the film as a whole – tells us more about today than about 1961 or 1962.

This much-anticipated film is the follow-up to director Rachid Bouchareb’s Days of Glory (2006), which stormed the French box-office to much praise and to quite direct political effect. The story of three Algerians who served in the French Army during World War II moved President of the Republic Jacques Chirac to end the “crystallization” of pensions for French military veterans from the republic’s former colonies; those who were still alive were to receive pensions similar to other French veterans. Like Days of Glory, Outside the Law opened at the Cannes Film Festival (2010), stars the well-known French actors Jamel Debbouze, Roschdy Zem and Sami Bouajila, and was Algeria’s Oscar nominee for best foreign film. Yet the new film was quite poorly received by French critics (historians, most particularly) and failed to attract a substantial audience. It has also inspired quite a bit of controversy, which was directly linked to this French reticence.

Before the film came out – and before he or anyone connected to him had seen the film – the right-wing (UMP) deputy Lionnel Luca attacked Outside the Law for its “revisionism” (read: negationism) which resulted, he claimed, in an “anti-French” screed. His knowledge of what was wrong with Bouchareb’s as-yet-unreleased opus came from an internal report on the script produced by the Service historique of the Ministry of Defense. The report claimed that the “the errors and anachronisms are so numerous and so flagrant that any historian can pick them out.” The “script contains so many untruths that it was clearly written without any serious historical research.” Luca expressed his shock that the French government had subsidized “this anti-French film.” A far-right “Committee for Historical Truth-Cannes 2010” – with the slogan “Crusade on the Croisette” – announced its intention to demonstrate at the Film Festival to deter politicians from “the contrition demanded by a band of Mafioso Jihadists.” The deputy, the mayor of Cannes, and over twelve hundred protestors gathered to “honor French victims of the Algerian war” and to protest the film’s “falsification of history.” Extensive security was deployed for fear, as Le Point magazine reported, that “bags of blood” would be hurled at the film’s stars and director on the red-carpeted steps, but there were no actual incidents. Still, Luca reported that “the film I just saw is partisan, militant, pro-FLN… It’s far worse that what we had heard.”[1]

When the film was released, French historians quickly stepped in to give their opinion of the film; most were very critical. The film does make numerous historical errors and is full of anachronisms. Yet one key element of many critiques was that the film was “pro-FLN.” On France-Culture, historian Pascal Ory affirmed that it was “98% an FLN film” while Fabrice d’Almeida stated that, if they saw the film, “the p’tit gars de banlieu would be subjected to the same bad history lesson they would have endured had they remained in Algeria.” Like most works of fiction, this film is not a history lesson. Nor is it particularly successful, at once overly long and too schematic in its narration. It has the weaknesses of Days of Glory but few of its strengths (although the acting remains strong). Negative comments by Ory and d’Almeida indicate, however, that historians should pay attention to the way French historians position themselves today.[2]

As the French historian Malika Rahal points out, the response to d’Almeida is that “the youths in the suburbs were born in France and could not have stayed in the Maghreb had they wanted to.” What is more, these historians have no clue what the Algerian government teaches its students. The film’s brief depiction of the violence in Sétif in May 1945 does present an inaccurate version of events that comforts Algerian nationalist sensibilities. The disdainful presentation of those Algerians who fought and worked with the French – notably the so-called harkis – and factually incorrect summary of what distinguished the FLN from its nationalist rival, the Algerian National Movement (MNA), clings tightly to versions of the past that the Algerian government advances. Yet the film repeatedly challenges FLN propaganda: the main action takes place in the metropole and most of the violence is perpetrated by the FLN on other Algerians, as the organization seeks to force them to support its goals, its methods, and its leadership. This vicious vanguardism is far from the FLN’s claims to be a “nation in struggle” and that the Algerian leadership still argues led to victory. Indeed, what is shocking is not that French official sources helped finance the film but rather that the Algerian government used up almost its entire film budget to support Bouchareb’s project.

More important, however, is the effort of French historians to monopolize the use of history tout court. The accusation that Bouchareb was an Algerian government mouthpiece manifests this. Besides another round of anti-Algerian racism, which surprises only because Days of Glory had been such a feel-good event, with an upbeat practical resolution, the debate around Outside the Law revealed the ongoing war many French historians have conducted against so-called porteurs de mémoires (bearers of memory). The term, as Jim House points out, reworks the porteurs de valises label affixed to the non-Algerian metropolitans who transported money, raised by the FLN from Algerian workers in France, to FLN contacts in Switzerland.[3] It is now used to castigate “victimization activists” whose claims to know and teach about the past arises from their suffering – real or affected – rather than the science of history. If professional historians were given the time, resources, and control of all discussions about the past, then the truth about the Algerian War – as well as slavery and overseas colonization more broadly – would emerge. These underlying suppositions are quite visible in the introductory pages of most recent French works on the Algerian conflict. They instruct the reader that what “historians” do is different. Only historians truly understand what to do with documents, so that what follows is “history” (good) rather than mere “memory” (bad). While I share their high estimation of rigorous archival research, I am also convinced that we, our students, and other people can get more from taking seriously the way other scholars, artists, or politicians discuss the past than from maintaining that only professional historians know what happened. Historians raise different questions, but their place is not to adjudicate debates of the day, or to try and close them down.

Bouchareb situates his film in the much-debated and very painful past that Algeria and France share. Like historians and the diverse porteurs de mémoires – from those who speak as pieds noirs, or harkis, or who were tortured by French forces – his work insists that this past still matters greatly to France as well as Algeria. Unlike some of the commentaries it provoked, Outside the Law has the merit of moving beyond a simple division between a “French” vision versus an “Algerian” vision and of ripping apart easy assumptions about who is good and who bad. Its story is not simply “pro-French”/“anti-French,” or “pro-FLN”/“anti-FLN.” Despite this particular film’s failure to attract a big audience or to change the debate that it re-ignited, one can only hope that more studies, works of fiction, or films – French, Algerian, or other – will be produced.

Until then, Bouchareb’s work can still be useful in our classrooms. I would not show it in its entirety. Because of its length and its other narrative weaknesses, this is not a film that will capture the attention of most viewers. Nor does it accurately capture key moments in the conflict over Algeria. Its depiction of the bidonville of Nanterre, however, is quite revelatory; more broadly, its focus on Algerians living around Paris speaks to many current discussions of immigration and October 17, 1961. It would also be interesting to have students compare this film’s analysis of the FLN’s attraction and victory with that proposed in the Battle of Algiers. Finally, if advanced students were interested in exploring how the “memory” versus “history” debate has developed as corporatist reaction as well as historical scholarship, the brouhaha around the film’s release could be a compelling topic.

- “Polemique autour du prochain film de Rachid Bouchareb,” Le Figaro (April 29, 2010); consulted on-line on March 4, 2011, at http://www.lefigaro.fr/festival-de-cannes/2010/04/29/03011-20100429ARTFIG00408-polemique-autour-du-prochain-film-de-rachid-bouchareb-.php . “Un millier de manifestants contre ‘Hors-la-loi’,” L’Express (May 21, 2010); consulted on-line on March 4, 2011, at http://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/politique/un-millier-de-manifestants-contre-hors-la-loi_893913.html.

- Their comments noted in Malika Rahal, “‘Hors-la-loi’: Un film dans l’Histoire,” Mediapart (October 3, 2010), consulted on March 4, 2011, at http://www.mediapart.fr/node/96333.

- Neil MacMaster and Jim House, Paris 1961: Algerians, State Terror, and Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 189.

Rachid Bouchareb, Director, Hors la loi (Outside the Law), France, Algeria, Belgim/Color, Tesallit/Agence Algérienne pour la Rayonnement Culturel (AARC)/EPTV/Tassili Films, etc., Running Time: 138 min.