Philip Nord

Princeton University

Christophe Boltanski’s La Cache is an evocation of the author’s grandparents, Etienne, a doctor, and Myriam, a novelist who published under the pseudonym Annie Lauran. The reader is introduced along the way to the author’s uncles and aunts, themselves a remarkable crew: Jean-Elie, a linguist, Luc, a sociologist, Christophe, an artist, and Anne, a photographer who like her mother used a professional name, in this case Anne Franski. It is a tight-knit clan that lives piled together in a multi-storied apartment on the rue de Grenelle in Paris’ well-heeled VIIe arrondissement. The author himself is part of the scene, moving in at the age of thirteen and camping out in his grandparents’ bedroom for a period alongside uncle Jean-Elie, both cocooned in sleeping bags.

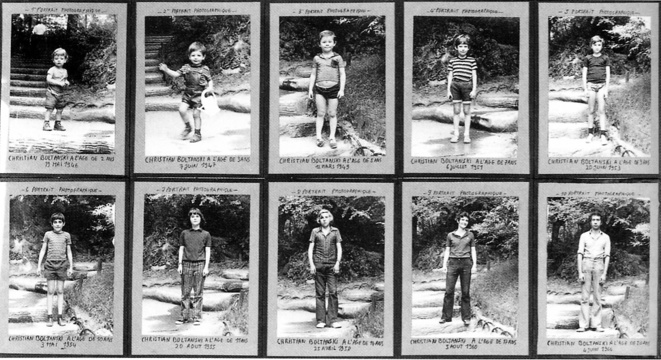

The Boltanskis are a family with secrets. Etienne Boltanski was born a Jew and spent twenty months in hiding during the Occupation. Christophe ferrets out the story, and in this respect La Cache resembles a budding genre of texts that track the consequences of the Holocaust across multiple generations. Daniel Mendelsohn’s The Lost (2006) was pioneering in the field, and Boltanski cites Mendelsohn by name. The author, in pursuit of a past shrouded in silence, talks to relatives, sifts through photos and memorabilia, visits archives, and even travels to the Boltanski hometown, Odessa. The writing is spiced with Yiddish phrases. Mère-Grand, as the grandmother is called, makes borscht. And the trauma of the Occupation years leaves its mark. Grandfather’s reappearance after the war frightens Luc, then still a boy; the author describes uncle Jean-Elie as tight-lipped, an observer of the code of Omertà; and Mère-Grand is determined to hold on tight to her brood. The children were not exactly home-schooled, but they spend a lot of time in the apartment away from class; girlfriends are not encouraged; and Jean-Elie in the end never seems to have moved out, inheriting the apartment when his parents die and staying on.

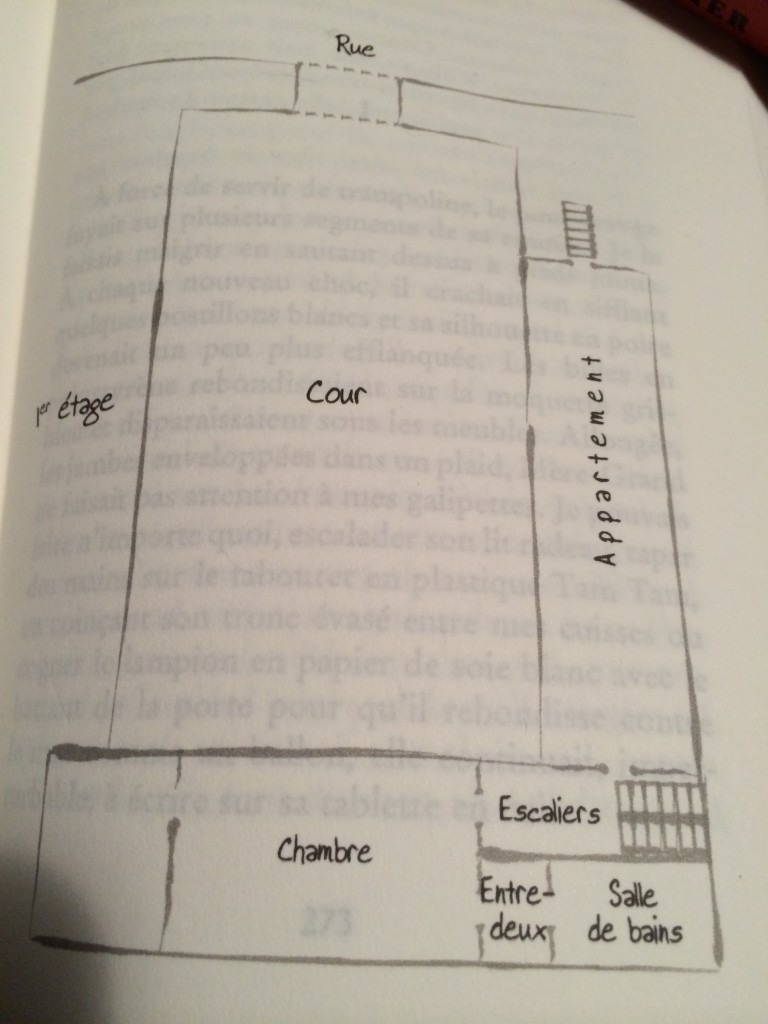

It would not be right, however, to sum up La Cache as a second-generation Holocaust memoir. The book’s dust jacket describes it as a “true novel,” and it behooves the reader to reflect for a moment on what such a descriptor might mean. Boltanski’s prose is rich in savory and well-chosen words. The writing is artful, and so too is the book’s construction. It is written as a tour of the apartment, starting with the family car parked in the courtyard just outside, then moving indoors to the kitchen, and after that proceeding room by room and floor by floor upward to the last space of all, the loft. Along the way the reader is treated to Boltanski’s childhood memories, playing at toy soldiers with uncle Christian in the salon or sledding down the steps from the first floor to the rez-de-chaussée on a pillow. The apartment is a rambling space, littered with furnishings and objects, and these are catalogued in wistful, sometimes humorous detail. Along the way, family stories are recounted that yield up a trove of revelations.

Figure 1: The Boltanski brothers in 1959 (Jean-Elie, Luc, and Christian) source: C. Boltanski, Catalogue of the books, 1992, n° 16 http://archives.carre.pagesperso-orange.fr/Boltanski%20Christian.html

Mère-Grand contracted polio as an adult, but she is a proud woman who refuses to use prosthetics or a cane. She was born into a large, Catholic family that was rightwing, a brother landing in trouble after the war because of too close ties to the Vichy regime. Her parents were cash-strapped, and she was sent as a girl to live with a wealthy benefactress in provincial Mayenne, a woman of faith and the author of pious texts. Mère-Grand, however, rebelled against the world of convention she was born into, marrying a Jewish man and becoming involved in Communist politics, but the revolt was not complete, for after all, she became, like her benefactress, a writer, and not just that, she inherited the benefactress’s land-holdings.

Figure 2 Christian BOLTANSKI: Photographie de ma petite soeur en train de creuser sur la plage de Granville. 1969. Same source.

Then there’s aunt Anne who turns out not to be the author’s biological aunt, for she was adopted and adopted under circumstances that are never spelled out.The professional pseudonym that she invents for herself, Anne Franski, is a melding of two names: Anne Frank and Boltanski, an understandable choice, it would seem, given the grandfather’s Jewish ancestry.

Yet the question of the grandfather’s Jewish identity turns out to be a vexed one. He was circumcised but not told that he was Jewish until later in life. He was from an immigrant family and in certain respects traced an upward trajectory that was characteristic of so many immigrant Jewish boys, distinguishing himself in school and going on to become a doctor. Yet, in the end, grandfather’s story was not so typical. He served in a medical capacity on the front lines in the Great War and was profoundly shaken by the experience. He returned an unsettled man and wound up seeking solace in the Roman Catholic faith. He converted, and when he later married, it was not in synagogue but in church.

As our cicerone conducts us from one space to the next, the complexities accumulate, and there is even some confusion. So many family members bear more than one name. Multiple generations are in play, and it is not always clear who belongs to which one. And then the pieces fall into place. That moment of clarity arrives in the chapter titled “Entre-deux.” The entre-deux is a liminal space, about the size of train compartment, located on the first floor between the bathroom and the grandparents’ sleeping quarters. It’s also elevated in relation to the nearby landing, reached by climbing a couple of stairs, and what that means is that there’s a hollow underneath that can be turned into a hiding place, la cache of the title.

This is indeed what happened during the war. In 1942, Mère-Grand, taking stock of the danger her husband is in, realizes that he has to vanish, and a scheme is concocted to make his disappearance convincing. The grandparents get a divorce. The story is circulated that Etienne Boltanski has moved to the southern zone, and it’s arranged to have letters written in his hand sent from there to Paris. Yet, all the while, grandfather is really concealed beneath the entre-deux, a secret that Jean-Elie is in on but not Luc. Grandfather comes out at night to sleep with Mère-Grand who in fact becomes pregnant. By a stroke of luck, the Liberation arrives before the baby, saving the family from some awkward explanations, and that is how uncle Christian came into the world.

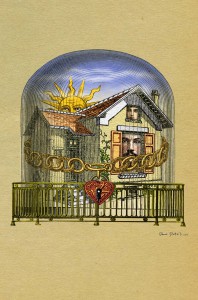

The “between two floors” is an actual space, the “belly button” of the household as the author describes it. But it’s also a way of being, the grandfather’s first of all, who is wedged between two faiths, Jewish and Catholic. It also the grandmother’s who owns property and counts mean-spirited Vichyssois among her relatives, even as she herself socializes with bohemian types and distributes the Party newspaper, L’Humanité, on Sundays. In fact, it is that of the whole Boltanski clan, and the author finds a telling image for this state of in-between-ness: the family Christmas tree which was decorated at the top with the yellow Star of David that the Occupation authorities had obliged grandfather to wear.

But what about the author himself? La Cache is a story about grandparents, but, of course, it is also one about Christophe Boltanski. He too has his secrets. His father, Luc, was an FLN sympathizer during the Algerian war, and his mother, unnamed, hid an FLN operative sought after by the police, who was later caught. The author’s parents went into hiding in their turn, not in “the hiding place” (though that option was considered), but elsewhere. Christophe was born not long thereafter, the circumstances of his own birth replicating those of uncle Christian.

And then, sometime in the mid-seventies for reasons never explained, the author leaves his own family to relocate to the rue de Grenelle sanctuary. He sleeps in the grandparents’ room but later moves upstairs to the loft. That’s where uncle Christian’s atelier is located, and at one end of the room, Luc fashions a space apart for his son, separated from the rest by a sliding panel. Here, Christophe settles in and pictures himself hunted after by enemies of all kinds. He imagines escaping through a skylight to the roof or concealing his presence altogether behind a fake wall, thereby transforming, if only in imagination, his own corner of the loft into a hiding place, yet one more. There are hiding places everywhere then: the entre-deux, Christophe’s bedroom in the loft, and, indeed, the rue de Grenelle apartment itself, understood as a refuge where the Boltanski tribe in its entirety can wall itself in against an unwelcoming world beyond.

Figure 5 source: http://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2015/08/27/les-boltanski-en-lieu-sur_4738260_3260.html

In this light, the notion of in-between-ness takes on yet one more layer of meaning. It is grandfather’s hiding space, of course. It is also that mix of religions that the author himself works so hard to sort out. He could have left it all behind after all. His mother wasn’t Jewish; his father was a convert; and he himself is named Christophe. Yet Boltanski opts instead to look through the drawers of his grandfather’s secretary and to pull out the yellow star that is stored within and bring it to view. But there is yet a third meaning to in-between-ness. The Boltanski family lives poised between its life inside the rue de Grenelle apartment and the world out-of-doors. The author talks of his father Luc struggling to escape, and he will make an escape of his own. Christophe Boltanski is drafted and performs his military service in Cairo working at a Francophone newspaper of progressive and cosmopolitan views, beginning a career in journalism and letters that he has pursued ever since. La Cache represents a going back, a return indoors, but a return in the company of readers who are introduced into a family circle that is bound tight: bound from without by the pressures of an often hostile world and bound from within by an intensity of emotion, centered on the indomitable and regal figure of the author’s Mère-Grand. It is with her death, that this “true novel” ends.

La Cache is a compelling book, deeply felt and crafted with art and feeling. It won the Prix Femina for 2015, and it is not hard to see why.

Christophe Boltanski, La Cache, Paris: Stock, 2015.