Charles Rearick

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

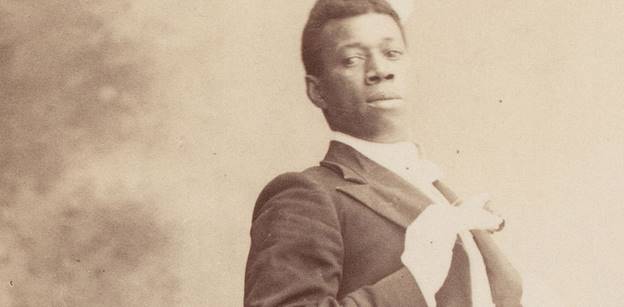

Chocolat is an entertaining biopic about the black clown who became a circus star in Paris around 1900. It recreates scenes from his routines in the ring, which the press covered amply. And it also shows many unrecorded incidents that the screenwriters have made up for their storytelling purposes. Which parts are invented, and which are documented? The viewer cannot tell. But there is a recent, extensively researched book that can help. Anyone interested can check the film version against the findings of a first-rate historian, Gérard Noiriel, whose book appeared about the same time as the movie (early 2016). After devoting six years of research on Chocolat, Noiriel came out with much more information and historical contextualization than were hitherto available. Nonetheless, the documentation remains scant, leaving many gaps. So he used generous doses of imagination to fill in a lot of blanks, and (with Noiriel’s input) the screenwriters used even more.

Chocolat is an entertaining biopic about the black clown who became a circus star in Paris around 1900. It recreates scenes from his routines in the ring, which the press covered amply. And it also shows many unrecorded incidents that the screenwriters have made up for their storytelling purposes. Which parts are invented, and which are documented? The viewer cannot tell. But there is a recent, extensively researched book that can help. Anyone interested can check the film version against the findings of a first-rate historian, Gérard Noiriel, whose book appeared about the same time as the movie (early 2016). After devoting six years of research on Chocolat, Noiriel came out with much more information and historical contextualization than were hitherto available. Nonetheless, the documentation remains scant, leaving many gaps. So he used generous doses of imagination to fill in a lot of blanks, and (with Noiriel’s input) the screenwriters used even more.

What makes the book unusual is that the historian has revealed the process of his research as well as his findings.[1] Through more than 500 pages, Noiriel recounts leads that took him not only into French archives, but also to Cuba, birthplace of Rafael Padilla, who became famous as Chocolat. In writing the book, Noiriel adopted a methodological precept that he took from Marc Bloch: historians should reveal how they found out what they recount. That includes telling about searches that did not uncover anything worthwhile. (Surely all of us have experienced that, but we do not write about it at length.) Further, Noiriel embraces the Romantic historiographical tradition of valuing imagination as a way of infusing life into relics from the past. He, like Jules Michelet, views the historian’s role as bringing the dead back to life. He identifies empathetically with Chocolat and even addresses personal letters to him (“tu”) throughout the book. Explicitly for Noiriel, Chocolat is a “hero.” All this opened the door wide to the filmmakers in their commercial-cinema project of portraying this historical figure.

What makes the book unusual is that the historian has revealed the process of his research as well as his findings.[1] Through more than 500 pages, Noiriel recounts leads that took him not only into French archives, but also to Cuba, birthplace of Rafael Padilla, who became famous as Chocolat. In writing the book, Noiriel adopted a methodological precept that he took from Marc Bloch: historians should reveal how they found out what they recount. That includes telling about searches that did not uncover anything worthwhile. (Surely all of us have experienced that, but we do not write about it at length.) Further, Noiriel embraces the Romantic historiographical tradition of valuing imagination as a way of infusing life into relics from the past. He, like Jules Michelet, views the historian’s role as bringing the dead back to life. He identifies empathetically with Chocolat and even addresses personal letters to him (“tu”) throughout the book. Explicitly for Noiriel, Chocolat is a “hero.” All this opened the door wide to the filmmakers in their commercial-cinema project of portraying this historical figure.

The movie begins with the hero’s first circus performances. An inter-title announces the period as 1897 and the place as northern France. Inside a small circus tent set up in a bucolic valley, the ringmaster dramatically introduces a “strange” and frightening figure, an African “cannibal,” “le roi nègre Kananga.” A wild-looking black man bursts in, startling and threatening audience members. This was anything but a clown act. Auditioning for the same small Delvaux circus was a clown named George Foottit (as his legal name was spelled), whose antics fail to impress the owner. The latter faults Foottit’s act for not being modern and spectacular. Foottit must look elsewhere for work. But before leaving, the clown sees in Rafael Padilla the potential for something new and different: forming a duo, with a white-faced dominator and his black-faced foil. Together they would perform pantomimes and sketches punctuated by slapping, kicking, chases, and some surprising turnabouts. On a nearby hillside Foottit tries out some rough knockabout–kicking his new partner, in his role as the auguste (the pitre or idiot, he explains). To his surprise, Padilla responds by kicking him down the hillside. That is just the first of Padilla’s self-assertive acts, albeit overshadowed by repeated humiliations.

The movie begins with the hero’s first circus performances. An inter-title announces the period as 1897 and the place as northern France. Inside a small circus tent set up in a bucolic valley, the ringmaster dramatically introduces a “strange” and frightening figure, an African “cannibal,” “le roi nègre Kananga.” A wild-looking black man bursts in, startling and threatening audience members. This was anything but a clown act. Auditioning for the same small Delvaux circus was a clown named George Foottit (as his legal name was spelled), whose antics fail to impress the owner. The latter faults Foottit’s act for not being modern and spectacular. Foottit must look elsewhere for work. But before leaving, the clown sees in Rafael Padilla the potential for something new and different: forming a duo, with a white-faced dominator and his black-faced foil. Together they would perform pantomimes and sketches punctuated by slapping, kicking, chases, and some surprising turnabouts. On a nearby hillside Foottit tries out some rough knockabout–kicking his new partner, in his role as the auguste (the pitre or idiot, he explains). To his surprise, Padilla responds by kicking him down the hillside. That is just the first of Padilla’s self-assertive acts, albeit overshadowed by repeated humiliations.

The early scenes show how the duo worked out fast-paced original twists in their clowning routines. Audiences respond to their new acts with laughter and delight. The circus owner and his wife enjoy the bigger crowds and bigger earnings, but they refuse Foottit’s plea for a raise. Then one day a leading Parisian circus director, Joseph Oller, shows up and offers a handsome salary for the duo to perform in his prestigious circus. They accept gleefully and depart for the capital. Padilla has to leave behind a girlfriend, a pretty young equestrian.

The early scenes show how the duo worked out fast-paced original twists in their clowning routines. Audiences respond to their new acts with laughter and delight. The circus owner and his wife enjoy the bigger crowds and bigger earnings, but they refuse Foottit’s plea for a raise. Then one day a leading Parisian circus director, Joseph Oller, shows up and offers a handsome salary for the duo to perform in his prestigious circus. They accept gleefully and depart for the capital. Padilla has to leave behind a girlfriend, a pretty young equestrian.

This entire first segment of the movie is fictional. By the year 1897 Chocolat was already a star in Paris. The small Delvaux circus did not exist. Rafael Padilla did not play the savage in such a circus. This was not where he met the clown George Foottit, and they did not work out their innovative act in such a venue. Foottit was not the creator of their act, and Rafael Padilla did not begin his career as a clown with George Foottit. He had already worked with several others.

Why so much misinformation in the first part? The scenes in the provinces provide a foundation for the rest of the story in several ways. First, they show the reactions of the rural population in an era when almost none had ever seen a dark-skinned man. Fear and racism are clearly manifested, along with reactions of curiosity and fascination. Secondly, the provincial-circus backstory makes the narrative arc simple and familiar: the protagonist rises from a backwater debut to go on to win a contract and stardom in Paris. The second part, however, is historically accurate: for ten years Chocolat performed in the cream of Paris circuses, the Nouveau Cirque in the Rue Saint-Honoré.

Why so much misinformation in the first part? The scenes in the provinces provide a foundation for the rest of the story in several ways. First, they show the reactions of the rural population in an era when almost none had ever seen a dark-skinned man. Fear and racism are clearly manifested, along with reactions of curiosity and fascination. Secondly, the provincial-circus backstory makes the narrative arc simple and familiar: the protagonist rises from a backwater debut to go on to win a contract and stardom in Paris. The second part, however, is historically accurate: for ten years Chocolat performed in the cream of Paris circuses, the Nouveau Cirque in the Rue Saint-Honoré.

The imagined episodes at the outset also help contrast the two main characters. George Foottit, the experienced clown, is ever serious and solitary. Foottit finds nothing that he can enjoy. He is the classic sad clown–sad not only in his performance face, but also in his everyday life, and funny only when working to make others laugh. He is a depressive and (the filmmakers suggest) sexually repressed. In one scene where he drinks alone in a bar, a young gay man offers him a good time; Foottit hesitates, anguished or tempted, but finally walks away. Meanwhile Rafael Padilla, acted with aplomb by Omar Sy, is spontaneous and happy-go-lucky, even ebullient when things go well, even in the small circus. As a big-draw performer in a top-flight Paris circus, he lives high, enjoying the fabled pleasures and luxuries of the great city. This leads him into risky behaviors that ultimately bring about his downfall: high-stakes gambling, excessive drinking, and drugs. He also lacks legal papers, particularly critical for a black immigrant, targeted by an ever-zealous police. At almost every turn, the racist hostility of many awaits him, especially outside the circus.

The imagined episodes at the outset also help contrast the two main characters. George Foottit, the experienced clown, is ever serious and solitary. Foottit finds nothing that he can enjoy. He is the classic sad clown–sad not only in his performance face, but also in his everyday life, and funny only when working to make others laugh. He is a depressive and (the filmmakers suggest) sexually repressed. In one scene where he drinks alone in a bar, a young gay man offers him a good time; Foottit hesitates, anguished or tempted, but finally walks away. Meanwhile Rafael Padilla, acted with aplomb by Omar Sy, is spontaneous and happy-go-lucky, even ebullient when things go well, even in the small circus. As a big-draw performer in a top-flight Paris circus, he lives high, enjoying the fabled pleasures and luxuries of the great city. This leads him into risky behaviors that ultimately bring about his downfall: high-stakes gambling, excessive drinking, and drugs. He also lacks legal papers, particularly critical for a black immigrant, targeted by an ever-zealous police. At almost every turn, the racist hostility of many awaits him, especially outside the circus.

The film does not reveal that Foottit was English and did not speak French well. As a foreigner, he had the same outsider status as Rafael Padilla, except for the color of his skin. He forms both a working relationship and a friendship with the immigrant “other.” Foottit is almost the only male in the film who interacts with Chocolat without blatant racism, but he is not wholly exempt from it–in the circus ring and beyond it. For one thing, he gives his partner only half of what he pockets himself.

Except for the small-circus owner’s malicious wife, the French women in the film exhibit no prejudice. Two fell in love with Chocolat. The first is Camille, the performer on horseback, who teaches Chocolat to read and write, introduces him to Shakespeare, and encourages him in his early efforts at clowning. The second is a Parisian mother of two, Marie Hecquet Grimaldi, who marries him, encourages him in his theatrical debut as an actor, and lovingly supports him to the end. (The moviemakers portray her as a nurse and a widow with two children, but according to the historical record she was a married woman who chose to live with Chocolat and then divorced her husband.)

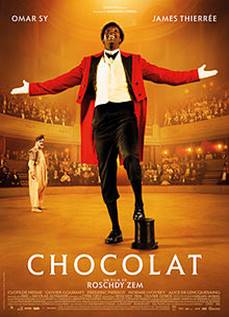

The glory time of Chocolat in the Nouveau Cirque is the high point of the narrative arc. Several slapstick sketches show him at his clowning best. Decked out in a brilliant red tailcoat, Chocolat shines as the cheery simpleton–not always as dumb as he appears–usually on the receiving end of slaps and kicks by the severe white-faced clown. The high-society audience responds to the duo with hearty laughter and applause. Chocolat was a celebrity. As a crowd-pleaser at Tout Paris‘s favorite circus, he earned big money and spent it on fine clothes, a new automobile, gambling, and Parisian women picked up in cabarets. He was the subject of an early Lumière movie, a figure in the Musée Grévin, and an icon in posters and merchandizing. He was the first black star in France, the object of adulation of both the well-to-do and children.

A scene at the Universal Exposition of 1900, however, inserts a troubling note. When Chocolat happens upon some black Africans on display as “savages,” one of them spots the impeccably dressed Rafael standing out amid the many French visitors and tries to communicate with him. But the differences (language first of all) are too great, and a dismayed Chocolat turns away, unsettled by their contrasting fates.

Having achieved acclaim as a circus clown, Rafael Padilla begins to question his identity and his place in society. He wants to be more than the slapped-and-kicked dimwit clown, the victim of his white partner. He longs to be recognized and respected, not caricatured or stereotyped. He wants to be an artist. Several experiences reinforce this. One is the trauma of spending time in jail as a sans-papier immigrant after the police stop him in the street. There he suffers sadistic torture by the police. Then a fellow prisoner, a Haitian intellectual, prods and taunts him to recognize his servile condition and the systemic racial injustice in French society. Afterward he somberly reflects on his life and remembers watching his enslaved father being ridiculed by white masters in Cuba. From then on, he begins asserting himself—first of all, by standing up to Foottit and the businessman Joseph Oller. Marie Hecquet Grimaldi, his beautiful Parisian bourgeoise mistress encourages him to pursue his acting ambition, introducing him to the theater director Firmin Gémier.

In the movie Rafael Padilla quits his partnership and clowning career abruptly during a performance at the Cirque Nouveau. After slapping a dumbfounded Foottit with unscripted force, he prances out of the ring alone in hopeful triumph (according to Noiriel’s research, the breakup did not happen that way). Outside the circus he had already pressed his luck too far by gambling and piling up ruinous debts. A Corsican underworld boss orders his thugs to catch Chocolat in the street, and they brutally beat him. But the decisive reversal of fortune comes just after he realizes his dream of acting Shakespeare’s Othello. The movie shows bits of the performance in Gémier’s avant-garde theater (actually, according to the historian, not mounting Othello or any of Shakespeare’s works). His acting debut goes well, but at the end racist men in the audience loudly reject him as an actor, shouting “scandale” and “back to the circus!”

The last part of the movie skips over almost a decade in which Chocolat faded from public view and fell on hard times. He died before his fiftieth birthday–in November 1917. The last scenes of the movie show an old, sick, and forgotten Padilla in his death bed in a shabby circus trailer in Bordeaux. The screenwriters work in some relief from the sad ending by having a humbled Foottit show up to pay homage to his former partner and reaffirm their friendship.

The last part of the movie skips over almost a decade in which Chocolat faded from public view and fell on hard times. He died before his fiftieth birthday–in November 1917. The last scenes of the movie show an old, sick, and forgotten Padilla in his death bed in a shabby circus trailer in Bordeaux. The screenwriters work in some relief from the sad ending by having a humbled Foottit show up to pay homage to his former partner and reaffirm their friendship.

In judging this movie and Noiriel’s historical work, we should note that the aim behind both was not just to present an entertaining historical drama. One of the objectives was to combat discrimination and racism–by telling the story of a black immigrant’s struggles and accomplishments against all odds. In an interview in Libération, Gérard Noiriel declared that he wanted to give young people a hero with whom they could identify–someone quite different from such classic figures as Jeanne d’Arc and Napoleon.[2]

Does the movie succeed? The answer is open to discussion. In my view, Chocolat does come across with some heroic traits–as a courageous, talented, inventive performer, who certainly suffered wrongs from the racism in French society. But it is hard to fit Chocolat into the long-established cultural frame of heroes, a tradition dominated by “great” military or political leaders and artists and writers, followed more recently by athletes and show-biz stars. Perhaps he can be viewed as a tragic hero, although his life did not have the classical ending of a decisive downfall. The last part of the movie–the vicious beating after out-of-control gambling, his failed effort as an actor, and his dying as a forgotten has-been—goes against the project of hero-making. The movie leaves him an isolated, down-and-out man on his deathbed. His mold-breaking accomplishments as a new kind of celebrity, challenging discrimination and racist mindsets in France, were obviously limited and transitory. Without suggesting anything like a “happy ending,” I was left thinking that more could be made of Chocolat’s longer-term contribution to French culture–as an innovative entertainer, a path-breaking black star, and a pioneer of therapeutic clowning in hospitals, for example. Such questions might be raised with students after a showing of the film.

Does the movie succeed? The answer is open to discussion. In my view, Chocolat does come across with some heroic traits–as a courageous, talented, inventive performer, who certainly suffered wrongs from the racism in French society. But it is hard to fit Chocolat into the long-established cultural frame of heroes, a tradition dominated by “great” military or political leaders and artists and writers, followed more recently by athletes and show-biz stars. Perhaps he can be viewed as a tragic hero, although his life did not have the classical ending of a decisive downfall. The last part of the movie–the vicious beating after out-of-control gambling, his failed effort as an actor, and his dying as a forgotten has-been—goes against the project of hero-making. The movie leaves him an isolated, down-and-out man on his deathbed. His mold-breaking accomplishments as a new kind of celebrity, challenging discrimination and racist mindsets in France, were obviously limited and transitory. Without suggesting anything like a “happy ending,” I was left thinking that more could be made of Chocolat’s longer-term contribution to French culture–as an innovative entertainer, a path-breaking black star, and a pioneer of therapeutic clowning in hospitals, for example. Such questions might be raised with students after a showing of the film.

The movie and the book have brought him back into public consciousness, but to what effect? Can the well-known French expression “je suis chocolat” (“I’m screwed / I’ve had it”) lose its negative meaning? The open question is whether the revived public memory will center on the talented, barrier-breaking performer and his brief time of glory or on the painful story of racism and injustice.

Roschdy Zem, Director, Chocolat (2016), France, Color, 119 min, Mandarin Films, Gaumont, Korokoro.

NOTES

- Gérard Noiriel. Chocolat: La véritable histoire d’un homme sans nom. Montrouge: Bayard, 2016.

- Interview of Gérard Noiriel by Natalie Levisalles, “Chocolat, tu t’es battu, tu as été l’acteur de ta vie,” in Libération, 6 January 2016.