Allan Greer

McGill University

Weakened by devastating epidemics and internal divisions, the Wendat (Huron) confederacy of today’s Ontario was crushed in massive raids carried out in 1649 by their Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) enemies. Among the thousands killed in this campaign were four French Jesuits, including two who were tortured to death. The Jesuits had been an important presence in the Wendat country for more than twenty years, though they had only managed to convert a fraction of the population to Catholicism. Yet the gruesome martyrdom of Jean de Brébeuf provided raw material for a historical legend (a term originally connected to the writing of saints’ lives) with Catholic and colonialist overtones that simultaneously memorialized this episode in the history of native North America and transformed it into a story about the courage of a white man in the face of “savage” cruelty.

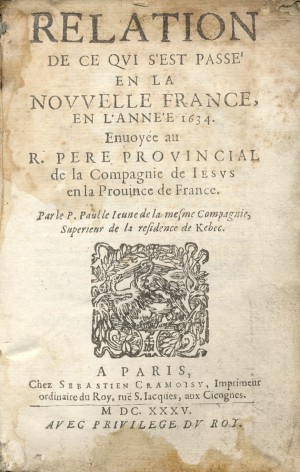

The Jesuit Relations, published in France between 1632 and 1673, provided creative writers of the twentieth century with rich ethnographic, historical and hagiographic materials to weave their own stories about the Jesuits, Wendat and Haudenosaunee. Black Robe, Brian Moore’s novel (1985), made into a film in 1991, is the best-known example; the film has found its way onto many a history course syllabus. While Moore made efforts to humanize his indigenous characters and to temper the European bias of his sources, Black Robe remains white man’s historical fiction, centered as it is upon the trials and tribulations of its Jesuit protagonist. (On this score, the film is a bit more balanced than the book, the result, I’m told, of pressure from indigenous cast members during the course of filming!). In the face of this long tradition of eurocentrism, Joseph Boyden’s The Orenda represents a heartening new departure, one that turns the tables on the Jesuits and brings native characters to the fore.

Without doubt, Boyden is a powerful storyteller, passionately engaged with issues of indigenous identity in Canada. His two previous works both featured native characters: Three Day Road follows two Cree snipers to the trenches of World War I, while Through Black Spruce enters the world of drug dealers and gangs on a reserve in the contemporary north. The Orenda is Joseph Boyden’s most ambitiously historical work to date. It is one thing to cast the mind back to 1914-18, quite another to imaginatively recreate a seventeenth-century setting, at a time when primordial cultural encounters were raw and fresh, and when all characters, native and European, inhabited a universe quite remote from our own. The novelist prepared himself for this journey with research in the Relations, as well as extensive reading in the historical and anthropological secondary literatures.

Without doubt, Boyden is a powerful storyteller, passionately engaged with issues of indigenous identity in Canada. His two previous works both featured native characters: Three Day Road follows two Cree snipers to the trenches of World War I, while Through Black Spruce enters the world of drug dealers and gangs on a reserve in the contemporary north. The Orenda is Joseph Boyden’s most ambitiously historical work to date. It is one thing to cast the mind back to 1914-18, quite another to imaginatively recreate a seventeenth-century setting, at a time when primordial cultural encounters were raw and fresh, and when all characters, native and European, inhabited a universe quite remote from our own. The novelist prepared himself for this journey with research in the Relations, as well as extensive reading in the historical and anthropological secondary literatures.

There is a lot of violence in Boyden’s books, almost as if the author were struggling against noble-savage sentimentalism and sanitized versions of First Nations history that airbrush out aspects that might shock contemporary western mores. In The Orenda, the violence can be almost overwhelming, focusing as it does, not only on armed conflict, but also on the “caressing” of war captives: the slow and exquisitely painful torture of prisoners that was practiced in Iroquoian societies of the past. Historians will be reminded of Inga Clendinnen’s head-on account of Aztec human sacrifice, to contemporary sensibilities the most troubling aspect of Aztec life; rather than soft-pedaling or ignoring human sacrifice, she thrusts its in the reader’s face and then works to understand it in the context of a given time and culture. Boyden deals similarly with Iroquoian torture, refusing easy moral solutions. What counts in the end is the way violence, whether Iroquoian torture or European criminal punishment of the period, is contextualized and balanced with due attention to other dimensions of the society. Like a good historian, Boyden tries to make war and torture comprehensible to readers by drawing unobtrusively on the ethnohistorical literature surrounding the Iroquoian “mourning war complex.” Even so, The Orenda is still a very gory book, one that edges close to the fine line dividing courageous realism from exploitive sensationalism.

The story opens with a dreadful massacre. A Wendat party led by the great warrior Bird surprises a small band of Haudenosaunee at their winter hunting camp and kills everyone except a young girl named Snow Falls. The captive girl is taken back to the Wendat land; Bird adopts her to replace his own daughters who had been killed by the Haudenosaunee in an earlier episode of this protracted struggle. At the same time, a Jesuit named Christophe (We’re on strictly first-name terms with the missionaries.) enters the scene, determined to bring civilization and religion to the benighted savages. There are recurrent armed clashes with the Iroquois, a Wendat visit to the French colonial post of Quebec, an epidemic of Old-World origin that leaves survivors bereaved and despairing. Christophe, eventually joined by Jesuit colleagues, slowly learns the language of the Wendat and acquires a more nuanced understanding of their culture. Snow Falls, another outsider with spiritual gifts, painfully adapts to the ways of her captors.

The story opens with a dreadful massacre. A Wendat party led by the great warrior Bird surprises a small band of Haudenosaunee at their winter hunting camp and kills everyone except a young girl named Snow Falls. The captive girl is taken back to the Wendat land; Bird adopts her to replace his own daughters who had been killed by the Haudenosaunee in an earlier episode of this protracted struggle. At the same time, a Jesuit named Christophe (We’re on strictly first-name terms with the missionaries.) enters the scene, determined to bring civilization and religion to the benighted savages. There are recurrent armed clashes with the Iroquois, a Wendat visit to the French colonial post of Quebec, an epidemic of Old-World origin that leaves survivors bereaved and despairing. Christophe, eventually joined by Jesuit colleagues, slowly learns the language of the Wendat and acquires a more nuanced understanding of their culture. Snow Falls, another outsider with spiritual gifts, painfully adapts to the ways of her captors.

Boyden wonderfully dramatizes aspects of the Wendat-French encounter as described in the pages of the Jesuit Relations. He nicely captures the linguistic gap in an early passage where Christophe (aka “the Crow” or “charcoal” in reference to the Jesuits’ black attire) struggles with the native language in an awkward attempt to proselytize Bird.

“Great Voice, he loves you,” he continues, pointing at me. “Great Voice is son child deer Christ. Christ kill for you to become him. Christ kill me. Die. Death for you. Christ.”…Long wood. Two woods.”…The Crow makes a chopping motion. “His hands are attached. His feet are attached,” he says. “Hurt. He dies you.” He points to me. “You die.” (57-58)

The author skillfully evokes the palisaded villages of the Wendat, the bark-covered longhouses, the boiling pots of sagamite (corn stew), the sounds and smells of village life. Woven into the gripping plot are countless realistic touches: Huron healing rituals, the great Feast of the Dead, etc. He also makes good novelistic use of the dilemmas and internal conflicts of both Wendat and Jesuits: the former resenting the missionaries’ insults to their culture but needing to forebear in the interests of maintaining good relations with the French, the latter vacillating between feelings of disgust for the “barbarism” that surrounds them and contrary feelings of admiration for a culture they are coming to understand.

That said, there are some serious problems with the way The Orenda portrays life in the seventeenth-century contact zone. Historians can be nit-picking killjoys when it comes to historical fiction, but I think it is more than carping to point out that one of the central plot elements of the novel, Bird’s ongoing effort to “adopt” the orphaned Snow Falls, is impossible. Iroquoian kinship in this period revolved around the matrilineal clan. An individual’s identity derived from her mother and her maternal kin. A male warrior like Bird might bring war captives back to the village, but only women could adopt them because women “owned” the families that were the only point of entry into this society. Partly because The Orenda devotes so much space to the daring exploits of brave warriors, with women, such as the sexy shaman Gosling, relegated to minor roles, readers may not realize just how much Iroquoian villages and Iroquoian families were female spaces.

That said, there are some serious problems with the way The Orenda portrays life in the seventeenth-century contact zone. Historians can be nit-picking killjoys when it comes to historical fiction, but I think it is more than carping to point out that one of the central plot elements of the novel, Bird’s ongoing effort to “adopt” the orphaned Snow Falls, is impossible. Iroquoian kinship in this period revolved around the matrilineal clan. An individual’s identity derived from her mother and her maternal kin. A male warrior like Bird might bring war captives back to the village, but only women could adopt them because women “owned” the families that were the only point of entry into this society. Partly because The Orenda devotes so much space to the daring exploits of brave warriors, with women, such as the sexy shaman Gosling, relegated to minor roles, readers may not realize just how much Iroquoian villages and Iroquoian families were female spaces.

In an effort, perhaps, to really “get inside the heads” of his seventeenth-century Hurons and French, Boyden chose a particularly difficult narrative technique. Alternating among his three principal characters, Bird, Snow Falls and Christophe, he tells his tale as a series of inner monologues, recounting episodes from the point of view of the Wendat warrior, the Iroquois captive and the Jesuit missionary, complete with their respective judgements and emotional reactions. It might have been easier to recount words and actions from an external vantage point, but The Orenda scrolls out as a procession of thought bubbles. That means that the author constantly faces the challenge of imagining, not only what his characters did and not only what they thought, but who/what they thought they were. What would the self-consciousness of a Huron man of this period have been? How would he have understood himself as an element of his clan, his nation: in relation to living Hurons and dead? What sorts of connections would he have assumed between his self and the selves of “non-human persons,” including different animal species and spiritual forces? None of us really knows what it felt like to be a Huron circa 1649, but Boyden’s narrative strategy forces him to invent such a consciousness. In places, his characters’ thought processes ring true; all too often their subjectivities seem to reflect twenty-first century understandings of human relations. Nowhere is this more evident than in the account of a wedding: the proud and anxious father of the bride ruminates over the young couple’s prospects, all very much in the style of a modern suburban patriarch.

The Jesuits of The Orenda are no more believable as seventeenth-century figures than are the Wendat. Two junior missionaries, Isaac and Gabriel, come across as slightly ridiculous caricatures. The author treats Christophe with more respect than the others, but gives him a rather narrow set of motivations and an impoverished consciousness. Stubborn and courageous, this Jesuit endures pain and misery, but for what? He seems to think that the Indians need to change their evil ways in order to avoid burning in Hell, but we get little sense of the man beyond that simple impulse. We learn nothing of his personal background; there are no traces of the classical education that Jesuits were famous for, little evidence of their profound ambivalence about contemporary European society, hardly a hint of the deep currents of mysticism that pervaded the New France missions. Instead Christophe seems to function as a stand-in for a very large and impersonal transhistorical force: the juggernaut of colonialism that would do its best to crush indigenous America under its wheels.

The Orenda has been hailed in Canada as a breakthrough novel that has brought native history and native literature to a broad public. Personally, I feel that Joseph Boyden’s two earlier books contributed more effectively to that laudable goal. For all its literary merits, The Orenda is not ideally suited for use in the history classroom. Better to put students directly in touch with the Jesuit Relations themselves.

Joseph Boyden, The Orenda, Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2013

Apart from being set in the 1600s, there is no content that

reveals the Wendat, Anishinaabeg, or Haudenosaunee’s deeply philosophical

relationship to the land, unless one considers trudging

through the snow on inadequately depicted snowshoes as profoundly insightful. In

spite of the author and many critic’s claim, The Orenda

does not offer any insight whatsoever into the spiritual worldview or

complexities of the indigenous peoples of the time. To claim the young female narrator and

her Anishinaabe mentor as ‘spiritually gifted” is ridiculing the depth and

significance of my spirituality as a traditional indigenous person. Boyden’s

depiction, and Wab Kinew’s defense of it, both ridicules and dishonors the

traditional spiritual knowledge and practice of the Anishinabeg, by reducing it

to trickery and mysticism (much like the conversion tactics of the Jesuits). There within lies a missed opportunity to truly craft a voice from the medicine woman’s perspective.This is a work of absolute fiction strictly based on the

historical writings of the Jesuit missionaries of the day, whose largely exaggerated

propaganda served to financially support their Christian mission. Boyden did

not dig deep enough (or at all?) into indigenous research to give his First

Nation portrayals accurate historical and cultural treatment. There was no reference to traditional

government structures in place at the time; no mention of a Council of Elders,

no reference to the matrilineal society in which they lived, and no referral to

traditional ceremony. Instead, Boyden portrays his Wendat characters as members

of a community void of structure and their own spiritual women, largely left to

fend for themselves within the confines of the clan. Additionally, the author draws

an unrepresented, insultingly shallow and stereotypical depiction of the

Haudenosaunee. Boyden depicts his indigenous world in the same primitive

light as 1950s textbook accounts. The novel is

preferentially Jesuit in perspective and effectively delves into the religious

plight of the Black Coats that came as part of a bigger social and political

agenda. These Jesuit-based accounts served to perpetuate the noble savage, the

warring savage, and the childlike savage needing civilization and enlightenment,

making Boyden’s work a regression of First Nation/Canadian relations. This work is a skewed and detrimental account presented -and sadly understood – as Canadian history, that is still trying to right itself.How terribly sad that yet again, the indigenous people of this land are

being stereotyped by, this time, their own Jesuit-educated writer who, by his

own Métis hand, brings his Native

ancestors and their descendants back into the spectrum of racist stereotypes.

It is already so very difficult being indigenous in this country, but more so

when we are betrayed by misguided public voices. If Boyden depended less

on the Jesuits’ often exaggerated historical accounts, he may have written a much

different book which, in turn, would have made a much deeper – and culturally

accurate – impression upon both worlds. Let us lay our tobacco down for our

ancestors and pray that one day, they will finally be understood – by firstly

our own and then – by misinformed others.

Pingback: Hurons and Jesuits Revisited: Joseph Boyden&rsq...