Neil McWilliam

Duke University

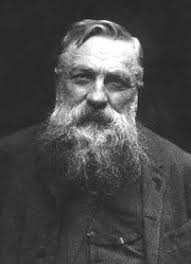

At the time of his death at the age of 77 on November 17, 1917, Auguste Rodin was the most celebrated sculptor – and possibly the most celebrated artist – the world had known since the neo-classical master Antonio Canova some hundred years earlier. Yet, while Canova’s career had largely consisted of a series of unalloyed triumphs, Rodin had been continually dogged by controversy, and his most ambitious commission, The Gates of Hell, for the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris, remains stubbornly incomplete. Despite an often contentious relationship with the public authorities, Rodin bequeathed the entire contents of his studio to the state in 1916, and the Hôtel Biron, which had been his base in Paris since 1908, was inaugurated as the Musée Rodin in August 1919. Recently reopened after extensive restoration, this shrine to the artist’s considerable oeuvre, supplemented by a major holding of the sculptor’s casts at his suburban studio in Meudon, ensures that Auguste Rodin is one of the best documented – and most exhibited – figures in the history of art.

The celebrations marking the centenary of Rodin’s death were truly international, with shows springing up from Brooklyn to Buenos Aires. Appropriately enough, however, the epicenter of festivities was Paris itself, where a comprehensive survey was mounted in the Grand Palais as Rodin. L’exposition du centenaire. Here, the artist was firmly inserted in a sculptural lineage designed to demonstrate “le génie puissant” of “ce poète de la passion, maître incontesté et monstre sacré” who “révolutionne la création artistique avant Braque, Picasso ou Matisse, et la fait à jamais basculer dans la modernité.”[1] To drive home the point, work by contemporary figures such as Joseph Beuys, Georg Baselitz and Anthony Gormley was rather incongruously scattered throughout the show to assert the master’s undiminished impact, while a whole gallery was devoted to artists active since the Second World War to demonstrate the lure of his expressive, agitated treatment of the sculpted form. Coming eight years after a show at the Musée d’Orsay that presented sculpture in Paris between 1905 and 1914 under the provocative title Oublier Rodin?, the Paris exhibition made an aggressive claim for the master’s historic centrality and persistent significance one hundred years after his death.

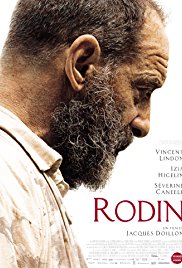

It seems all the stranger, then, that the Musée Rodin, at the forefront of this concerted effort to further burnish the sculptor’s already outsize reputation, should have played a central role in the production of Jacques Doillon’s biopic Rodin, a film so leaden and inert as to effectively embalm the master as a “mort vivant.” Doillon, a veteran of French cinema known for such feature films as La Pirate (1984) and Ponette (1996), initially embarked on a documentary project which developed into a film biography, scripted by the director himself, that focuses on Rodin’s career and personal life over a thirty-year period beginning in 1880. Coinciding with major projects such as The Gates of Hell, The Burghers of Calais, and, most insistently, the monument to Balzac, Doillon’s film covers decades that are pivotal for Rodin’s artistic achievement and hard-earned public recognition. Yet this period in Rodin’s life has also become widely known due to his liaison with Camille Claudel, a sculptor almost twenty-five years his junior who entered his studio in 1884 and had a relationship with him that lasted almost a decade. It ended in acrimony at the master’s refusal to abandon his longstanding partner, Rose Beuret, for the talented younger woman. Already the subject of a 1988 feature film, Bruno Nuytten’s Camille Claudel, the relationship provides the armature for Doillon’s narrative, though the ripe melodrama of the earlier work (“You and I are freaks of nature […],” “You’re dreaming, Rodin, we’re two ghosts in a wasteland”) is largely avoided in this generally austere version of events. The contrast is highlighted by the casting of the principals in the two movies: Isabelle Adjani and Gérard Depardieu turned in larger-than-life performances, pouting and declaiming, where their successors – Izïa Higelin as Claudel and Vincent Lindon as Rodin – opt for a less histrionic, more subdued tone.

In contrast to the operatic quality of Nuytten’s work, Doillon’s film is conceived as a chamber piece – a mood captured in Philippe Sarde’s discreetly effective, and sparingly used, soundtrack. Izïa Higelin is notably self-effacing as Claudel, and her psychological crisis emerges all the more convincingly by avoiding Adjani’s scenery-chewing excess.

In contrast to the operatic quality of Nuytten’s work, Doillon’s film is conceived as a chamber piece – a mood captured in Philippe Sarde’s discreetly effective, and sparingly used, soundtrack. Izïa Higelin is notably self-effacing as Claudel, and her psychological crisis emerges all the more convincingly by avoiding Adjani’s scenery-chewing excess.  As Rodin, Vincent Lindon adopts a haunted, depressive demeanor, scarcely roused into life even when indulging in a joylessly solemn threesome with his students Gwen John and Hilda Flodin or chasing the stolid Rose Beuret around the bedroom in her heavy flannel nightdress. Lindon most closely resembles the sculptor as captured by Claudel in her bust of 1888-89 (Musée Rodin, Paris) – his head emerging behind a long, closely cropped beard, with high cheek bones and a heavy brow, his expression aspiring to tortured profundity but conveying little more than gloomy reserve. For much of the film, Rodin appears wounded and embattled, retreating from the outside world – of which we see little in the film’s two hours – into the private realm of the studio, where he rarely raises his voice above a mumble made all the more impenetrable by the whiskers enveloping the actor’s mouth.

As Rodin, Vincent Lindon adopts a haunted, depressive demeanor, scarcely roused into life even when indulging in a joylessly solemn threesome with his students Gwen John and Hilda Flodin or chasing the stolid Rose Beuret around the bedroom in her heavy flannel nightdress. Lindon most closely resembles the sculptor as captured by Claudel in her bust of 1888-89 (Musée Rodin, Paris) – his head emerging behind a long, closely cropped beard, with high cheek bones and a heavy brow, his expression aspiring to tortured profundity but conveying little more than gloomy reserve. For much of the film, Rodin appears wounded and embattled, retreating from the outside world – of which we see little in the film’s two hours – into the private realm of the studio, where he rarely raises his voice above a mumble made all the more impenetrable by the whiskers enveloping the actor’s mouth.

In some ways, Lindon’s taciturn delivery perfectly complements the unconvincingly wooden dialogue, which is the central flaw in this prosaically didactic production. French defenders of Rodin have berated “Anglo-Saxon” critics – who have overwhelmingly dismissed the film as clichéd, tedious, and pretentious – for failing to perceive the film’s profundity and poetry, misled by their naïve expectations of the biopic genre. Yet such a defense fails to reckon with the crudely reductive ways in which Rodin, his friends, lovers, and pupils, discuss both the artist’s career in particular and the creative process in general. Much of the film consists of a series of disquisitions on art, predominantly between Rodin and Claudel, but also conscripting contemporaries such as the painters Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne, and writers Octave Mirbeau and Rainer Maria Rilke. These are overburdened with expository baggage (“On a vécu nos plus belles années à Bruxelles, Rose,” “Avec l’Âge d’airain, j’avais été accusé de tricherie. D’avoir moulé directement sur le corps de mon modèle … Il y a trop de vie dans mes sculptures”[2]), sophomoric aesthetic “insights” (“tout ce que je veux faire, c’est d’être vrai” – on Balzac before a skeptical committee headed by Émile Zola, for whom “Vous avez réduit Balzac à une masse informe”)[3] and awkward critical scene-setting (Mirbeau tells Rodin that with the Balzac “Vous avez provoqué le dernier scandale du siècle, après Manet et Courbet. Vous ne vous rendez pas compte. Votre Balzac est une oeuvre totale. À côté de votre colosse, les autres sculptures ont l’air de poupées de coiffeur,”[4] before launching into an interminable list of supporters – Gauguin, Renoir, Monet, etc., etc. – who have contributed to a subscription for the work’s completion). Doillon’s film is, of course, often visually striking: dominated by pale colors in the dusty-white décor of the studio, the apparitional gleam of the sculptor’s plaster models, and the equally spectral effect of the artists’ enveloping smocks. But this visual sheen (often drowned in symbolically resonant shadows) hardly salvages enough poetry in the face of the relentlessly prosaic quality of the dialogue.

In some ways, Lindon’s taciturn delivery perfectly complements the unconvincingly wooden dialogue, which is the central flaw in this prosaically didactic production. French defenders of Rodin have berated “Anglo-Saxon” critics – who have overwhelmingly dismissed the film as clichéd, tedious, and pretentious – for failing to perceive the film’s profundity and poetry, misled by their naïve expectations of the biopic genre. Yet such a defense fails to reckon with the crudely reductive ways in which Rodin, his friends, lovers, and pupils, discuss both the artist’s career in particular and the creative process in general. Much of the film consists of a series of disquisitions on art, predominantly between Rodin and Claudel, but also conscripting contemporaries such as the painters Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne, and writers Octave Mirbeau and Rainer Maria Rilke. These are overburdened with expository baggage (“On a vécu nos plus belles années à Bruxelles, Rose,” “Avec l’Âge d’airain, j’avais été accusé de tricherie. D’avoir moulé directement sur le corps de mon modèle … Il y a trop de vie dans mes sculptures”[2]), sophomoric aesthetic “insights” (“tout ce que je veux faire, c’est d’être vrai” – on Balzac before a skeptical committee headed by Émile Zola, for whom “Vous avez réduit Balzac à une masse informe”)[3] and awkward critical scene-setting (Mirbeau tells Rodin that with the Balzac “Vous avez provoqué le dernier scandale du siècle, après Manet et Courbet. Vous ne vous rendez pas compte. Votre Balzac est une oeuvre totale. À côté de votre colosse, les autres sculptures ont l’air de poupées de coiffeur,”[4] before launching into an interminable list of supporters – Gauguin, Renoir, Monet, etc., etc. – who have contributed to a subscription for the work’s completion). Doillon’s film is, of course, often visually striking: dominated by pale colors in the dusty-white décor of the studio, the apparitional gleam of the sculptor’s plaster models, and the equally spectral effect of the artists’ enveloping smocks. But this visual sheen (often drowned in symbolically resonant shadows) hardly salvages enough poetry in the face of the relentlessly prosaic quality of the dialogue.

Doillon’s film is one of the latest representatives of a remarkably durable cinematic genre – the artist biopic – which in the last two or three years alone has drawn on the lives of figures such as J.M.W. Turner, Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Egon Schiele, and Paula Modersohn-Becker.[5] Since Vincente Minelli’s seminal (and still remarkably watchable) Lust for Life, the 1956 film biography of Van Gogh, the biopic has played an important role in fueling the persistent myth of artistic difference, exploring the psychological burden of the creative personality, and the irreducible otherness of the artist’s lifestyle and moral habitus. Often highly colored or downright lurid, the biopic fictionalizes the artist’s life in ways that often show scant regard for historical accuracy (or even rudimentary credibility: Mick Davis’s 2004 Modigliani, starring Andy Garcia, is exemplary in this – and only this – regard). At times, directors have attempted to reverse the trend, demythologizing lives all too prone to the mystifying gaze – here Maurice Pialat’s Van Gogh (1991, starring Jacques Dutronc) is a worthy, though deeply dull, experiment in treating the painter as a credible individual rather than a walking cliché. To a more limited degree, Doillon seems to have aspired to something similar by freeing Rodin from the more restrictive accoutrements of the fabled genius. In doing so, however, he has left a hollowed out, tedious figure who spends much of his time talking about art with a banality that belies the extraordinary talent manifested in the works that surround him. It is in this painful discrepancy between an etiolated filmic discourse and the plenitude of Rodin’s achievement that one is, I believe, justified in accusing Doillon’s work of pretention, as many critics have done. Its pretention lies not in any high-flown language or abstruse references but in the bathetic misfit between the central character’s inability to convince us of his aesthetic insight and creative power, and the actual achievement his legacy represents. Doillon’s Rodin (and his acolytes) sound pretentious because they voice views and ideas that claim to provide insight, but finally obfuscate (and irritate) in their stale superficiality. Though the viewer is offered interesting glimpses of the practical production of sculpture, the mind behind this creative enterprise remains elusive. In this regard, despite Doillon’s frequently didactic tone, one learns little of substance: as an introduction to the artist – in a classroom setting, for example – although the film presents potentially useful details of studio practice, it is hard to see it as entertaining, enlightening or enthusing its audience.

Doillon’s film is one of the latest representatives of a remarkably durable cinematic genre – the artist biopic – which in the last two or three years alone has drawn on the lives of figures such as J.M.W. Turner, Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Egon Schiele, and Paula Modersohn-Becker.[5] Since Vincente Minelli’s seminal (and still remarkably watchable) Lust for Life, the 1956 film biography of Van Gogh, the biopic has played an important role in fueling the persistent myth of artistic difference, exploring the psychological burden of the creative personality, and the irreducible otherness of the artist’s lifestyle and moral habitus. Often highly colored or downright lurid, the biopic fictionalizes the artist’s life in ways that often show scant regard for historical accuracy (or even rudimentary credibility: Mick Davis’s 2004 Modigliani, starring Andy Garcia, is exemplary in this – and only this – regard). At times, directors have attempted to reverse the trend, demythologizing lives all too prone to the mystifying gaze – here Maurice Pialat’s Van Gogh (1991, starring Jacques Dutronc) is a worthy, though deeply dull, experiment in treating the painter as a credible individual rather than a walking cliché. To a more limited degree, Doillon seems to have aspired to something similar by freeing Rodin from the more restrictive accoutrements of the fabled genius. In doing so, however, he has left a hollowed out, tedious figure who spends much of his time talking about art with a banality that belies the extraordinary talent manifested in the works that surround him. It is in this painful discrepancy between an etiolated filmic discourse and the plenitude of Rodin’s achievement that one is, I believe, justified in accusing Doillon’s work of pretention, as many critics have done. Its pretention lies not in any high-flown language or abstruse references but in the bathetic misfit between the central character’s inability to convince us of his aesthetic insight and creative power, and the actual achievement his legacy represents. Doillon’s Rodin (and his acolytes) sound pretentious because they voice views and ideas that claim to provide insight, but finally obfuscate (and irritate) in their stale superficiality. Though the viewer is offered interesting glimpses of the practical production of sculpture, the mind behind this creative enterprise remains elusive. In this regard, despite Doillon’s frequently didactic tone, one learns little of substance: as an introduction to the artist – in a classroom setting, for example – although the film presents potentially useful details of studio practice, it is hard to see it as entertaining, enlightening or enthusing its audience.

None of this is to underestimate how hard it is to convincingly convey a sense of the creative act and the sensibility behind it – not that creation should be understood as mysterious or mystical, but that it is a careful, deliberative process all too easily transformed into a reductively impassioned tussle with the void. Different directors have more or less successfully animated their subjects with some semblance of psychological credibility and creative insight – Peter Watkins’s extraordinary, painstaking Edvard Munch of 1974 is perhaps the supreme example – but often enough the artist biopic is an exercise in reaffirming the foundational myths of creative individuality and the heavy psychological toll it reputedly takes. Doillon’s Rodin is a deeply despondent individual who seemingly achieves serenity only in the absorption of modeling or drawing. Rodin ends with the master sitting before a dais on which two female models cavort and contort as his hand unthinkingly traces their forms on a seemingly inexhaustible pile of drawing paper. At the end of a film in which the sculptor has experienced – and inflicted – more than his fair share of unhappiness through his relations with women seemingly ready to sacrifice themselves at the altar of genius, Doillon offers us the familiar cliché of the female nude as an object of aesthetic gratification, of disinterested contemplation and transcendence, liberating the creator from the ordeals of the world. Tormented by public incomprehension and the emotional turmoil of a traumatic relationship (from which – unlike Claudel – he emerged unscathed), the artist seemingly comes to life, revitalized by visual sensation – beyond words.

None of this is to underestimate how hard it is to convincingly convey a sense of the creative act and the sensibility behind it – not that creation should be understood as mysterious or mystical, but that it is a careful, deliberative process all too easily transformed into a reductively impassioned tussle with the void. Different directors have more or less successfully animated their subjects with some semblance of psychological credibility and creative insight – Peter Watkins’s extraordinary, painstaking Edvard Munch of 1974 is perhaps the supreme example – but often enough the artist biopic is an exercise in reaffirming the foundational myths of creative individuality and the heavy psychological toll it reputedly takes. Doillon’s Rodin is a deeply despondent individual who seemingly achieves serenity only in the absorption of modeling or drawing. Rodin ends with the master sitting before a dais on which two female models cavort and contort as his hand unthinkingly traces their forms on a seemingly inexhaustible pile of drawing paper. At the end of a film in which the sculptor has experienced – and inflicted – more than his fair share of unhappiness through his relations with women seemingly ready to sacrifice themselves at the altar of genius, Doillon offers us the familiar cliché of the female nude as an object of aesthetic gratification, of disinterested contemplation and transcendence, liberating the creator from the ordeals of the world. Tormented by public incomprehension and the emotional turmoil of a traumatic relationship (from which – unlike Claudel – he emerged unscathed), the artist seemingly comes to life, revitalized by visual sensation – beyond words.

Jacques Doillon, Director, Rodin (2017), Color, 116 min, France, Belgium, USA, Les Films du Lendemain, Artémis Productions, Wild Bunch.

NOTES

- “The powerful genius” of “this poet of passion, unquestioned master and giant” who “revolutionized artistic creation before Braque, Picasso or Matisse, and moved it definitively towards modernity.” From the publicity for the exhibition on http://www.grandpalais.fr/fr/evenement/rodin-lexposition-du-centenaire (page consulted January 18, 2018).

- “We spent our best years in Brussels, Rose,” “With the Age of Bronze they accused me of trickery. Of having taken a cast directly from my model’s body … There is too much life in my sculptures.”

- “The only thing I want is to be true”; “You have reduced Balzac to a shapeless mass.”

- “You provoked the century’s final scandal, after Manet and Courbet. You fail to recognize that. Your Balzac is a total work of art. Next to your colossus, other sculptures look like hairdressers’ dummies.”

- Mike Leigh, Mr. Turner, starring Timothy Spall (2014); Danièle Thompson, Cézanne et moi starring Guillaume Gallienne, (2016); Édouard Deluc, Gauguin – Voyage de Tahiti, starring Vincent Cassel (2017); Dieter Berner, Egon Schiele: Tod und Mädchen, starring Noah Saavedra (2016); Christian Schwochow, Paula, starring Carla Juri (2016). Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s 2017 Loving Vincent broke new ground in a well-worn genre by constructing a 94-minute film entirely of stop-motion images based on Van Gogh’s painted oeuvre.