Gregory Monahan

Emeritus, Eastern Oregon University

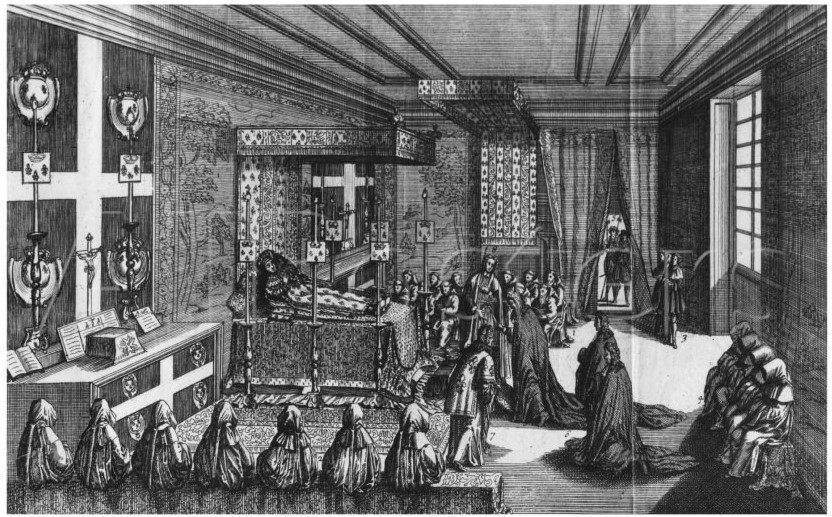

Louis XIV carefully staged the story of his life. That story included a large cast of characters in his court, and the king enjoyed the life-long process of “blocking” his life with them. For those new to that theatre term, “blocking” refers to placing characters in specific locations on a stage in any given scene in order to move the action forward. The king employed an extensive court ceremonial toward this end, using it to enhance not only his own authority, but that of those he favored, who could then “block” their own stories with further “cast” members in a kind of complex, cascading series of plays that moved the system of patronage and clientage from the halls of Versailles deep into the provinces of the French kingdom. When the king realized he was dying in August 1715, he staged that process as he had staged so many others. “I have lived among the people of my court; I want to die among them. They have followed the entire course of my life; it is just that they see me finish.”[1]

That line is not in Albert Serra’s film La Mort de Louis XIV, but it might as well be, since various members of the king’s court are often present around his bed during the film. The Catalonian director is best known for iconoclastic art house films that star amateurs and often feature minimalist sets, but here, he has changed his style completely. Casting professionals, led by Jean-Pierre Léaud, (who began his career as a fourteen-year-old boy in François Truffaut’s 1959 film, Les Quatre Cent Coups) as the king, he also recreates the king’s state bedroom at Versailles in luxurious detail and costumes his characters realistically. With the exception of the first scene, in which the king is being wheeled through his gardens in his “chaise roulante,” the entire 112-minute film takes place in the royal bedroom, the king ensconced in his bed as the theatre of his death unfolds. Aside from the king himself, the main characters are Guy-Crescent Fagon, the chief royal physician, and Louis Blouin, first valet of the king’s bed chamber. Others are present in smaller roles, including the king’s second wife, Madame de Maintenon, the chancellor Daniel Voysin, the royal surgeon Georges Mareschal, and a number of other courtiers and doctors.

In filming this last event of the king’s long life—he was a few days shy of 77 when he died—Serra could draw upon a number of sources. Philippe de Courcillon, marquis de Dangeau, kept a daily journal of events at court for over thirty years. He was allowed into the king’s bed chamber and left the most detailed account of his final illness.[2] The more famous memoirist of the period, Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon, also left a detailed account, although he depended more on the reports of witnesses than on personal experience like Dangeau.[3] Serra himself has mentioned Dangeau, and it is obvious in watching the film that he researched the last two weeks of the king’s life.

That last point takes us to the first question any historian always poses about any historical film. Is it “accurate”? That is always a fraught question for any film made in the present about the past, since it poses all kinds of questions about what “accurate” really means, but rather than fall into a thicket of post-structuralist analysis, I think I can say that the answer, for the most part, is “fairly accurate.” Most of the events that occur around the king’s bed in the film are attested in the sources, even if Serra has reordered some of them, left others out, and invented dialog. The king is shown getting the last rites much later than he did, for example, and a scene in which he arrogantly demands water from a crystal goblet is almost certainly invented, but he did suffer from constant thirst, and he did get the last rites. Serra gives us the famous scene of the king’s brief (and, in this telling, rather touching) speech to his five-year-old great-grandson and heir in which the old king famously advised the boy not to love war so much and to get along well with his neighbors—as clear a case of “do what I say, not what I did” as anyone is ever likely to hear.

But we do not get other speeches, such as the one to his courtiers about their having served him well, or his various conversations with his legitimized sons or his nephew the duc d’Orléans, the future regent, or even a speech to his old friend the Maréchal duc de Villeroy, the future king’s governor, and one of Louis XIV’s oldest friends, that allegedly left the old maréchal in tears. Serra has said that he would have liked to include more of these, but that they would have slowed the film too much, certainly an understandable decision. Likewise, while the bedroom looks fairly accurate, the bed is situated for filmic purposes so that the king can easily see out into the adjoining cabinet, but the royal bed was actually located in the back of a fairly large room, and no such view would have been possible. The bed curtains are always shown drawn back when they would often have been closed, and the king is often pictured on his bed wearing a large and formidable wig, when he did not do so at night. The film implies that Madame de Maintenon did not want to be present, but there is no sign of such reluctance in the sources, and she was there most of the time. In a particularly interesting moment, the king breaks the fourth wall by staring directly at us, as if to accuse us of insufficient respect, but, alas, with Mozart’s 1782 Mass in C Minor playing in the background. It is a great piece of music, but something by Lully might have been less anachronistic.

That said, other scenes are reproduced faithfully, and many of these involve the royal physicians, who struggled to treat an illness they soon realized was terminal. One recent historian has argued persuasively that the king suffered from advanced type-two diabetes brought on by a gargantuan and often uncontrolled appetite, especially for sweets, and contemporary accounts of his constant thirst and the gangrene that began in his left foot and eventually killed him, certainly support that hypothesis.[4] Fagon diagnosed sciatica in the beginning and ordered that the king’s leg be wrapped in warm cloth and that he drink ass’s milk. Later, when a fever was confirmed, Fagon gave the king cinchona, a tree bark concoction containing quinine. Contemporaries and historians have taken him to task for this misdiagnosis, but the physical signs of gangrene did not appear on the king’s leg until fairly late in his illness, and, in Fagon’s defense, the king had often suffered from various forms of pain in his limbs, including repeated attacks of gout.[5] Interestingly, at no time in this last illness was the king bled. Louis XIV did not like the procedure and occasionally vetoed it during his lifetime (probably helping to prolong his life), but the sources do not indicate that there was even a suggestion of this procedure during this last illness.

The film largely treats Fagon and the royal physicians more generously than historians have done. Fagon was, in fact, devoted to science, within the parameters of the Galenic paradigm still dominant at the time. He had gained considerable prestige by virtue of the simple fact that his royal patient had lived so long (as had he—Fagon was the same age as the king, though he looks younger in the film), and he commanded an army of 30 people—other doctors, surgeons, apothecaries, gardeners, and servants—to attend to the king’s health. Saint-Simon thought him “obstinate,” but even if true, such a trait was hardly unusual at the court of the sun king, including in the memoirist himself. Fagon did finally call in doctors from the Sorbonne for a consultation, and they all concluded that gangrene had begun. That confirmed the king in the knowledge that he would not survive this illness, beginning the cascade of speeches mentioned earlier. As the film shows, toward the end, a country physician named Le Brun showed up at the palace with an elixir he swore would cure the king’s gangrene. Lacking any other options, the royal physicians acquiesced and allowed the king to drink it, which he dutifully did. It didn’t work, of course, and the film includes an interesting conversation between the physicians and Le Brun about the efficacy of his elixir. This section ends with Fagon urging the king to have Le Brun arrested as a charlatan, but that would appear to be an invention, since no source I have seen testifies to such an action (Dangeau simply says he ran off when it looked like his medicine wouldn’t work). This rather bizarre intervention showed to what lengths the physicians were willing to go to keep the king alive, and it also underlines another theme, attested by other sources, that his physicians often treated the king’s body as a kind of laboratory for various treatments.[6] Louis XIV tolerated all this, allegedly saying at one point “one must follow the orders of one’s physicians.” Modern patients might well sympathize.

If the film makes any serious error, it is in underestimating just how much work the king continued to do during his last illness. He persisted in holding meetings of his councils and working individually with his ministers from his bed until just a few days before his death, and he often had himself carried to his wife’s apartments at night to hear music and chat with courtiers, until the pain became so extreme he simply didn’t enjoy it anymore. This king was deeply devoted to his royal tasks, and he seldom allowed any of his many illnesses and ailments to interfere if he could possibly avoid it, a devotion on which contemporaries often remarked. But, again, filming endless council meetings or sessions in which the king studied correspondence with his ministers would not exactly aid the pacing of a film that is already remarkably static in scene and action.

If the film makes any serious error, it is in underestimating just how much work the king continued to do during his last illness. He persisted in holding meetings of his councils and working individually with his ministers from his bed until just a few days before his death, and he often had himself carried to his wife’s apartments at night to hear music and chat with courtiers, until the pain became so extreme he simply didn’t enjoy it anymore. This king was deeply devoted to his royal tasks, and he seldom allowed any of his many illnesses and ailments to interfere if he could possibly avoid it, a devotion on which contemporaries often remarked. But, again, filming endless council meetings or sessions in which the king studied correspondence with his ministers would not exactly aid the pacing of a film that is already remarkably static in scene and action.

Indeed, it may seem from this description that Serra’s film will be about as interesting as watching paint dry, but I did not find it so. Perhaps there is simply the sense of being a voyeur, but the film offers some interesting observations about early modern medicine as well as a fairly good take on the court of France’s most famous king at the very end of his reign. Whether undergraduate students would find it too slow I must leave to my colleagues to judge. The Avengers it is not, but it is definitely worth a look, especially for historians of science, medicine, and the courts of early modern monarchies. If it concentrates almost entirely on the king’s physical body rather than the symbolic one so famously analyzed by Ernst Kantorowicz (whose glory his successors would try to live up to) it does so in a way that the king himself might have approved.[7] Indeed, given his devotion to the theatre of his own life, the only difference could well be that, given the choice, Louis XIV would certainly have insisted on directing the film himself.

Albert Serra, Director, La mort de Louis XIV/The Death of Louis XIV, 2016, 115 min, Color, France, Spain, Portugal, Capricci Films, Rosa Filmes, Andergraun Films, Bobi Lux.

NOTES

- Jean Buvat, Journal de la Régence, cited in Joel Cornette, La mort de Louis XIV. Apogée et crépuscule de la royauté (Paris: Gallimard, 2015), p. 14. Despite the fact that the latter book shares its title with the film, it is largely concerned with analyzing the history of the monarchy using the king’s death as a fulcrum.

- Philippe de Courcillon, marquis de Dangeau, Journal du marquis de Dangeau avec les additions inédites du duc de Saint-Simon 19 vols. (Paris : Firmin Didot, 1854-1860), 16:9-11; 16:97-136.

- Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon, Mémoires de Saint-Simon, ed. Arthur de Boislisle, 43 vols. (Paris: Hachette, 1879-1928), 27:176-211; 27:257-295. Those seeking an account in English can consult Mark Greengrass’s fine translation of François Bluche’s biography of the king, since that author used Dangeau, Saint-Simon, and others in his own detailed narrative: François Bluche, Louis XIV, trans. Mark Greengrass, (New York: Franklin Watts, 1990), 599-613.

- Stanis Perez, La santé de Louis XIV. Une biohistoire du roi-soleil (Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2007), 133.

- One scene in which a collection of prosthetic eyeballs painted to simulate various ailments are compared to the king’s own eye is clever, but I can find no evidence that such a practice ever existed, even though seventeenth-century Paris was a center for the production of prosthetic eyes.

- They even kept a detailed journal of the king’s ailments and their various treatments. Unhappily, that journal ended in 1711, but it is still a valuable source for early modern medicine in general and the health of Louis XIV in particular: A. Vallot, A. Daquin, et G.-C. Fagon, Journal de Santé de Louis XIV (Grenoble: Jérôme Millon, 2004). This edition has a fine introduction by Stanis Perez. The notion of learning from their mistakes is encapsulated in the film’s clever last line, but I will allow those who want to see the film to enjoy that without a spoiler from me.

- Ernst Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1937 [reprint, 2016]).