Sandrine Sanos

Texas A & M University, Corpus Christi

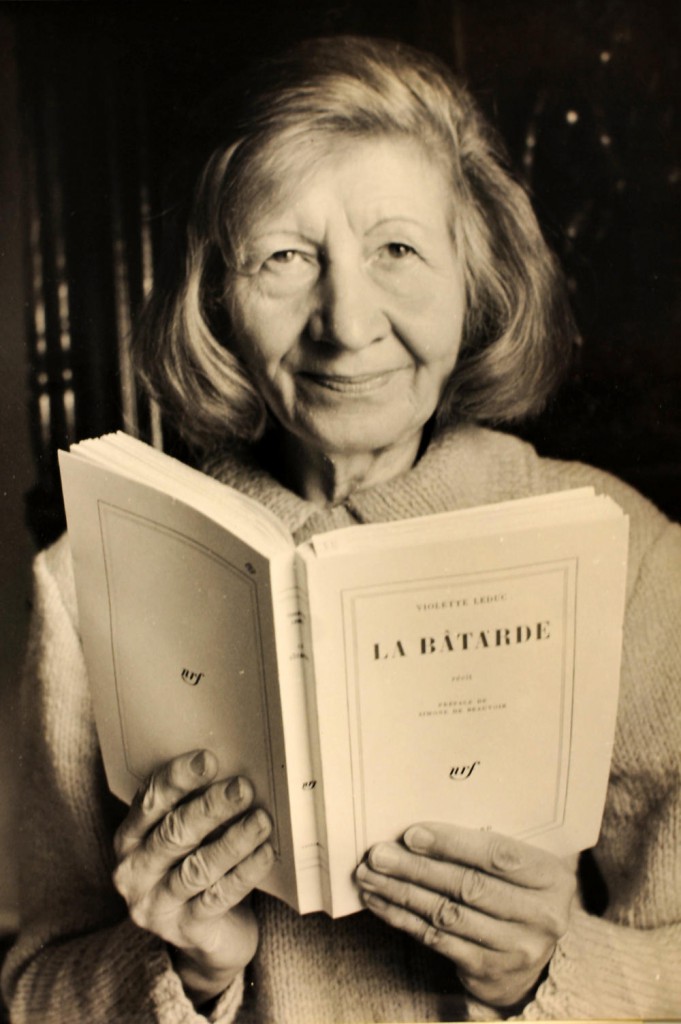

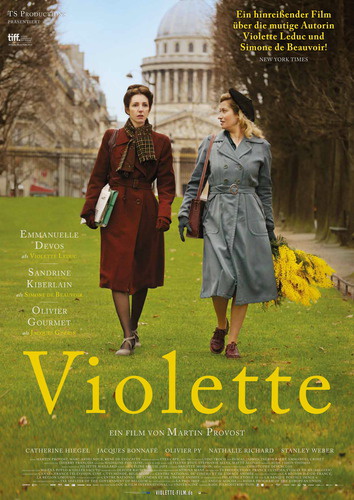

In 1964 Simone de Beauvoir wrote a long and eloquent preface for Violette Leduc’s autobiography, The Bastard [La bâtarde]. She praised the book for revealing “a woman turning to her self’s innermost secret and telling her story with the most daring honesty as if there was no one around to listen.” Leduc’s work told the story of her illegitimate birth, her cold and uncaring mother, her lesbian relationships, an unhappy marriage and abortion, life during the war, poverty, and black market activities, and her fateful meeting with second-rate gay writer, Maurice Sachs, who first encouraged her to write. For Beauvoir, Leduc’s prose revealed “a world full of noise and fury, where love can often take the shape of hatred, where a passion for life exhausts itself into screams of despair; a world devastated by loneliness […].” Martin Provost’s 2013 film, simply titled Violette, faithfully brings to life Leduc’s life. Yet, despite its promises, moments of emotional strength, and the praise it has garnered, the film’s conventional imagination and academic style fail to evoke Leduc’s’ “world of noise and fury.”

The biopic is certainly in vogue these days, with a renewed interest in the postwar era and the “trente glorieuses.” Violette was released but months before films on other famous postwar figures, such as the celebrated account of Yves Saint Laurent’s life, YSL by Jalil Lespert (that his partner Pierre Bergé approved), soon followed by an “unauthorized” Saint-Laurent by Bertrand Bonello.[1] Like these, Provots’s film eschews conventional chronology. Instead, the focus is on the making of a writer, beginning in 1942 when Leduc embarked on her first autobiographical story, ending with the publication of La Bâtarde in 1964 when she finally achieved recognition. Violette draws its veneer of authenticity and historical accuracy from the participation of Leduc’s champions, René de Ceccatti (who co-authored the script) and Carlo Jansiti (the author of the only biography to this day)[2]

The biopic is certainly in vogue these days, with a renewed interest in the postwar era and the “trente glorieuses.” Violette was released but months before films on other famous postwar figures, such as the celebrated account of Yves Saint Laurent’s life, YSL by Jalil Lespert (that his partner Pierre Bergé approved), soon followed by an “unauthorized” Saint-Laurent by Bertrand Bonello.[1] Like these, Provots’s film eschews conventional chronology. Instead, the focus is on the making of a writer, beginning in 1942 when Leduc embarked on her first autobiographical story, ending with the publication of La Bâtarde in 1964 when she finally achieved recognition. Violette draws its veneer of authenticity and historical accuracy from the participation of Leduc’s champions, René de Ceccatti (who co-authored the script) and Carlo Jansiti (the author of the only biography to this day)[2]

Leduc’s life was as tumultuous and troubled as her prose was evocative and transgressive. Beauvoir argued her works embodied the “victory of freedom over fate.”[3] However, unlike her friend and fellow author Jean Genet, whose career was also launched by Sartre and Beauvoir, Leduc has since been mostly forgotten in the canon of French literature. Leduc’s autobiographical novels could be said to have originated the genre of “autofiction” long before novelist Serge Doubrovsky coined the term and the recent trend represented by Guillaume Dustan and Christine Angot. Leduc, whom Genet described as “an extraordinary woman [who is] crazy, ugly, cheap, and poor” but possesses an “incredible talent,” memorably transgressed post-war France’s social conventions and embodied its contradictions—ready-made for portrayal on the screen.[4]

Leduc was born in northern France, the illegitimate child of Berthe Leduc who, as a maid, had had an affair with the son of her bourgeois employers. Leduc always depicted herself as an ugly “bastard” who was both unwanted and unloved. After a few years at a girls’ boarding school where she had a passionate affair with a classmate, Leduc moved to Paris in the late 1920s. Like the interwar “garçonnes” that preoccupied many contemporary critics, Leduc lived an independent life, collecting articles for the Plon publishing house. She moved in with Denise Hertgès, with whom she lived until the mid-1930s.[5] But life was difficult. Her relationship with Denise behind her, in 1939 Leduc married. The union was short-lived and unhappy; Violette fell pregnant and had an abortion. Separated from her husband, Leduc embarked on a journalistic career, meeting and falling in love with the writer Maurice Sachs. Leduc’s impossible love for gay men characterized her life. In 1942, she followed Sachs to Normandy where they survived thanks mostly to Leduc’s blackmarket activities. It was Sachs who encouraged her to write, and this became another mythical story of origins that Leduc repeatedly evoked.

Back in Paris with a completed manuscript of L’Asphyxie, Leduc brought it in February 1945 to Beauvoir (whose 1943 L’Invitée she had loved). Impressed by Leduc’s prose, Beauvoir recommended the work to Albert Camus, who published it in his Gallimard collection, “l’Espoir,” in 1946. From then on, Beauvoir and Leduc began a life-long relationship, meeting every two weeks to talk about literature and Leduc’s writing. It was Beauvoir who introduced Leduc to Genet. They became friends (Genet dedicated Les Bonnes to her). In 1948, Leduc published her bold novel L’Affamée (a declaration of love to Beauvoir),with the financial support of her friend, the wealthy perfume industrialist Jacques Guérin (another gay man Leduc fell in love with). The book met with the same silence as her previous work. In those years Leduc was able to survive thanks to Beauvoir and Sartre’s decision to provide her with a monthly allowance that supposedly came from her publisher Gallimard. After her 1954 Goncourt Prize for Les Mandarins, Beauvoir covered it alone, until Leduc’s 1964 success made her financially independent.

Her third novel, the 1955 Ravages, was censored because of its explicit description of lesbian sex (those passages would be published separately in 1966 under the title,Thérèse et Isabelle, once Leduc had become a recognized novelist). While the young author Françoise Sagan became an overnight sensation, Leduc languished. She fell into a deep depression, fuelled by fantasies of persecution, and, in 1956, she was interned for a while in a psychiatric hospital She began working on La Bâtarde, which she published in1964. It was an immediate success and sold over 170,000 copies in a few days.[6] At almost sixty years old, Leduc’s life suddenly changed.

Her third novel, the 1955 Ravages, was censored because of its explicit description of lesbian sex (those passages would be published separately in 1966 under the title,Thérèse et Isabelle, once Leduc had become a recognized novelist). While the young author Françoise Sagan became an overnight sensation, Leduc languished. She fell into a deep depression, fuelled by fantasies of persecution, and, in 1956, she was interned for a while in a psychiatric hospital She began working on La Bâtarde, which she published in1964. It was an immediate success and sold over 170,000 copies in a few days.[6] At almost sixty years old, Leduc’s life suddenly changed.

Provost brings Leduc’s literary voice to the screen through voice-overs, which give viewers a sense of Leduc’s prose. Moreover some of the film’s dialogue comes straight from her writings, especially in expository scenes. The film sets the tone by opening with Leduc’s arrest for blackmarket activities during the war. Viewers hear Leduc explaining how “ugliness” defines one: “Ugliness in a woman is a mortal sin. If you are beautiful, you are the one everyone admires in the street. If you are ugly, you are the one everyone looks at in the street.”

Leduc’s life is then divided into seven titled “chapters,” that each depict a person or place that shaped Leduc’s life: 1. Maurice (Sachs), 2. Simone (de Beauvoir), 3. Jean (Genet), 4. Jacques (Guérin), 5. Berthe (Leduc), 6. Faucon, 7. La Bâtarde. The film relies on the engrossing performances of actors who are each made to embody a temperament rather than reproduce the real-life personages. Emmanuelle Devos, who plays the title character, embodies Leduc’s ugliness, difficult life, ambivalences, neuroses, and passions. Sandrine Kiberlain becomes an aloof and self-possessed Simone de Beauvoir and Jacques Bonnaffé is a convincing Jean Genet. Leduc’s mother, Berthe, is impressively played by Comédie Française sociétaire, Catherine Hiegel, just as her friend Jacques Guérin is brought to life by Olivier Gourmet, and Oliver Py plays the troubling and troublesome writer Maurice Sachs.

The film well illustrates the difficulties that plagued Leduc’s life: her constant need for money—she regularly complains to Beauvoir, Guérin, and Genet about her lack of a regular income—and the specter of poverty –with, notably, a moving scene where Leduc is shown cleaning a piece of beef covered with maggots. Physical spaces play an important role in the film: from the claustrophobic one-bedroom apartment with its faded wallpaper, in which Leduc lives and writes obsessively, filmed in shades of browns and greys, to the sunny and warm-toned outdoor scenes of Leduc walking and  writing in the arid and mesmerizing Provence countryside, where she will eventually settle, and the film suggests, find her “true voice.” These contrast with Beauvoir’s bourgeois apartment and millionaire Guérin’s opulent office. Space also symbolizes the interior lives of characters, just like the colors of Leduc’s wardrobe (always in blue, red, or yellow) tell viewers her moods, and demarcate her from other characters: for instance, in an early scene, we see Leduc in a bright cobalt blue coat and red dress chasing Beauvoir who sports a deep red coat and blue dress—for Provost, they are two female authors mirroring one another.

writing in the arid and mesmerizing Provence countryside, where she will eventually settle, and the film suggests, find her “true voice.” These contrast with Beauvoir’s bourgeois apartment and millionaire Guérin’s opulent office. Space also symbolizes the interior lives of characters, just like the colors of Leduc’s wardrobe (always in blue, red, or yellow) tell viewers her moods, and demarcate her from other characters: for instance, in an early scene, we see Leduc in a bright cobalt blue coat and red dress chasing Beauvoir who sports a deep red coat and blue dress—for Provost, they are two female authors mirroring one another.

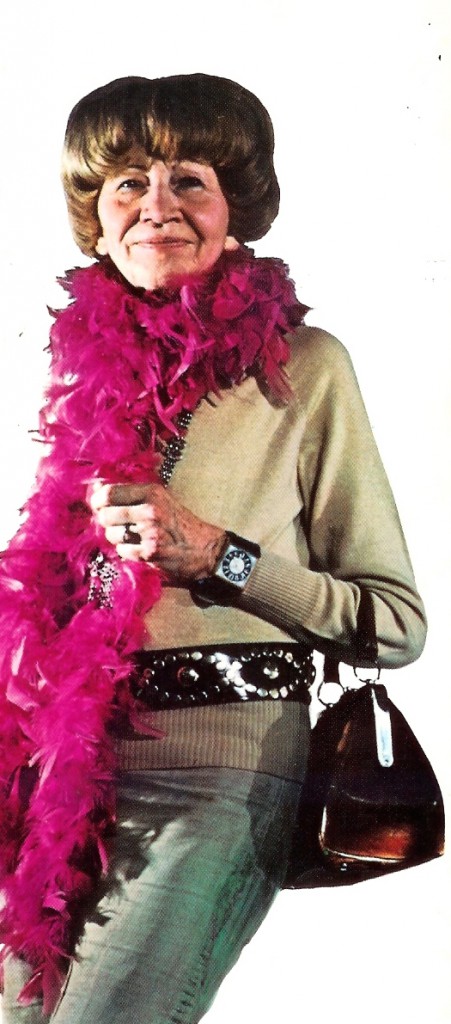

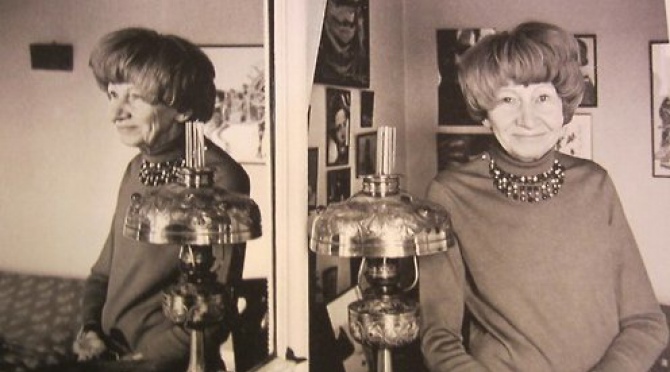

Unfortunately, while Devos proves especially apt at portraying Leduc’s needy and insatiable demand for love from those unable to reciprocate (like Guérin whom she manipulated and tried to seduce) as well as her stubborn determination and narcissistic self-pity, we see little of the flamboyance, wit, and originality that captivated those who became her friends. As her friends and biographer have insisted, Leduc was both a miser (she often spoke in 1970s interviews of her own “avarice”) and consumed by a need for money and “coveted objects” that she fetishized in her life and her writing.[7] She was also a striking figure who fascinated precisely because she cloaked her “ugliness” with an eccentric and luxurious fashion-sense (as Beauvoir described in her preface) [Here, Devos’ Leduc is neither flamboyant nor excessive (or one might venture, unattractive) enough, making it difficult to grasp the excesses in Leduc’s character. There is little of the wry and self-deprecating humor that was as much Leduc’s hallmark as her “exasperating self-pity.”[8] Leduc, in Provost’s rendition, is an “hysterical woman” rather than an intriguing puzzle and a complex literary voice.

Ultimately, especially for those who may already know Leduc’s work, the film flattens what could have been an especially rich rendition of an extraordinary character and novelist who lived through eventful times. One of the major failures of the film is its reliance on the tired cliché of the “madwoman” of genius that the director had mined in his previous film, Séraphine.[9] We see Sachs pushing Leduc to write out of frustration, which she does as if she were a vessel discovering the sublimating powers of fiction. Writing is portrayed as a self-evident act that only needs to be revealed and Provost’s Leduc is reduced to nothing more than a “tortured artist.” But what makes Leduc fascinating is that she was always a voracious reader, passionate about literature, who remained outside the small Parisian intellectual world of letters. Leduc had adored André Gide and Marcel Jouhandeau’s novels, and they inspired her first book. Even after her work was recognized and embraced by writers such as Camus and Cocteau, Leduc still felt on the margins of this literary world. The film erases Leduc’s love of literature and the fact she had written in other venues before Sachs is shown urging her to in 1942, better to emphasize her distance from the world of letters in its portrayal of the literary genius. Leduc’s “discovery of literature” is shown as pure accident (she finds Beauvoir’s 1943 novel at someone’s house, although it was her friend, Alice Cerf, who had recommended it to her in the same way she encouraged Leduc to send her novel to Beauvoir. Leduc had also frequented Adrienne Monnier’s bookstore).[10] In this way, Violette offers a female version of the lone romantic genius.

For Leduc writing was enmeshed with her relationships, especially with Beauvoir, who was all at once mentor, editor, friend and Leduc’s literary executor.[11] The two female authors sadly become clichés in Provost’ film: Beauvoir is reduced to only two obsessions, the fate of women (as if she were already the feminist she became in the 1970s) and literature. The postwar years, however, also inaugurated Beauvoir’s involvement in politics, including her anguished obsession with the Algerian War of Independence (as exemplified by the 1962 publication of Djamila Boupacha) and her hope for socialist revolutions. Leduc and Beauvoir’s literary relationship rested on the ways Leduc daringly portrayed the female body, sexuality, and motherhood using an autobiographical mode, especially since Beauvoir was also invested in writing the self, beginning her memoirs in the late 1950s. While both authors echoed one another, they were also strikingly different and class played its part in their relationship, a fact that remains muted in the film. The film also erases the more complicated nature of these women’s relationships, reducing it to Leduc’s unrequited love for Beauvoir. Leduc indeed adored Beauvoir, but she was, at the same time, more circumspect about her work: she found Beauvoir’s novels of unequal quality and was critical of the ways Beauvoir had portrayed female sexuality in The Second Sex, especially lesbian sexuality (just as she was critical of Genet’s Les Bonnes). In short, Leduc, who once said she the writers she most admired were Genet and Beckett, had an assured literary aesthetic. Beauvoir championed Leduc’s work (she was published by Les Temps Modernes in 1945 next to Richard Wright), but Beauvoir proved a rather heavy-handed editor who “softened” Leduc’s graphic prose and erotic descriptions.[12] Beauvoir was also much more of a friend to Leduc than has usually been acknowledged.[13] Beauvoir often mentioned Leduc in her memoirs, since her life, she explained, “had closely mingled” with hers.[14] (Leduc was convinced she had modeled the character of Paule and her mental breakdown in Les Mandarins on her).

“Violette Leduc, la chasse à l’amour” – Extrait from Les Films du Poisson on Vimeo.

Just as simplification characterizes the portrayal of Beauvoir and Leduc’s life-long friendship, sexuality is portrayed as a self-evident and uncomplicated fact in Leduc’s life. It is not that the film refuses to show how Leduc loved both women and men or that she often fell in love with unattainable objects of desire. It does offer some striking moments that speak to the complexities and ambiguities of Leduc’s emotional and sexual life: Leduc’s hallucinatory dreams of the dead Maurice Sachs at her bed, kissing Beauvoir, and most moving, a scene where Leduc ‘sees’ her ageing mother, pregnant in wedding attire, hitting her own stomach to “get rid of Violette.” Ultimately, the film privileges Leduc’s affair with a younger bricklayer –with whom, she wrote, she experienced an orgasm for the first time—at the expense of her relations and passionate friendships with other women.[15]. In contrast, Leduc’s relations with Denise (Hermine in the film) appear desexualized. Her relationship with Beauvoir might have illustrated this well: especially since Beauvoir took inspiration from Leduc’s life and writing for her Second Sex chapter on “The Lesbian,” which Leduc and her friends considered a failure.[16] In part, Beauvoir found in Leduc a writer who was not scared to write the very graphic ways in which the body was lived, the messiness of sex, the pains of unrequited and narcissistic love at a time when sexuality was very much on people’s minds and becoming an object of politics and literature.

It may be that Provost’s choice to portray Leduc’s life as a self-contained world, without any historical context, forecloses viewers’ understanding of the transgressive nature of her work and the “marginality” Leduc embodied yet never shied away from.[17] The film unfolds outside of historical time without any sense of the ways French society was profoundly changing, when Leduc, Beauvoir, and Genet’s writings were both symptoms and harbingers of these shifts. At the same time as Leduc’s 1955 work, Ravages, was released with passages censored, contraception and abortion (still banned) were becoming public issues, especially after the creation of the Planning Familial (Planned Parenthood) in 1956. Leduc published her tale of a woman’s complicated and ambivalent relation to motherhood and sexuality before the explosion on the literary scene in the mid-1950s of authors such as Nathalie Sarraute and Marguerite Duras, or the polemic surrounding the publication of Pauline Réage’s Histoire D’O or Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse.[18] Sex was on people’s minds but Leduc’s controversial descriptions of sex between women or where “man was made an object of desire” was still too shocking for readers then, even as depictions of female sexuality were becoming more commonplace. By the time La Bâtarde was published in 1964, other scandals had prepared the ground: Bardot’s “Lolita syndrome” (as Beauvoir termed it) had both shocked and enthralled viewers, while Resnais and Duras’ 1959 blend of trauma, violence, memory, and love in Hiroshima Mon Amour had become a worldwide sensation.[19] In short the context was different and Leduc’s works finally found an audience.

It may be that Provost’s choice to portray Leduc’s life as a self-contained world, without any historical context, forecloses viewers’ understanding of the transgressive nature of her work and the “marginality” Leduc embodied yet never shied away from.[17] The film unfolds outside of historical time without any sense of the ways French society was profoundly changing, when Leduc, Beauvoir, and Genet’s writings were both symptoms and harbingers of these shifts. At the same time as Leduc’s 1955 work, Ravages, was released with passages censored, contraception and abortion (still banned) were becoming public issues, especially after the creation of the Planning Familial (Planned Parenthood) in 1956. Leduc published her tale of a woman’s complicated and ambivalent relation to motherhood and sexuality before the explosion on the literary scene in the mid-1950s of authors such as Nathalie Sarraute and Marguerite Duras, or the polemic surrounding the publication of Pauline Réage’s Histoire D’O or Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse.[18] Sex was on people’s minds but Leduc’s controversial descriptions of sex between women or where “man was made an object of desire” was still too shocking for readers then, even as depictions of female sexuality were becoming more commonplace. By the time La Bâtarde was published in 1964, other scandals had prepared the ground: Bardot’s “Lolita syndrome” (as Beauvoir termed it) had both shocked and enthralled viewers, while Resnais and Duras’ 1959 blend of trauma, violence, memory, and love in Hiroshima Mon Amour had become a worldwide sensation.[19] In short the context was different and Leduc’s works finally found an audience.

The 1950s were the time of the Indochina and Algerian wars. Bars and cabarets had made Saint-Germain and Montparnasse once more fashionable while the Algerian conflict generated turmoil in working-class Paris, where police increased their presence and surveillance of Algerian immigrants. OAS bombings filled the news. None of this features in the film. Although Provost’s lush cinematography (thanks to Yves Capes) shows beautiful interiors, meant to reflect, in part, the centrality of Leduc’s inner life, Paris appears to be deserted, serving merely as a flat backdrop. In doing this, the director is attempting to recreate Leduc’s vision of Paris in her writings, something only those familiar with her work would realize.[20] The film’s academic realism may be too tame to suggest how Leduc’s life and prose can illustrate a moment in France’s obsession with what Judith Coffin has termed “mid-century sex.”[21]

The 1950s were the time of the Indochina and Algerian wars. Bars and cabarets had made Saint-Germain and Montparnasse once more fashionable while the Algerian conflict generated turmoil in working-class Paris, where police increased their presence and surveillance of Algerian immigrants. OAS bombings filled the news. None of this features in the film. Although Provost’s lush cinematography (thanks to Yves Capes) shows beautiful interiors, meant to reflect, in part, the centrality of Leduc’s inner life, Paris appears to be deserted, serving merely as a flat backdrop. In doing this, the director is attempting to recreate Leduc’s vision of Paris in her writings, something only those familiar with her work would realize.[20] The film’s academic realism may be too tame to suggest how Leduc’s life and prose can illustrate a moment in France’s obsession with what Judith Coffin has termed “mid-century sex.”[21]

The film might work effectively in the classroom if only shown in part: for instance “chapter 2: Simone,” which follows Leduc’s life from the end of the war and her meeting with Beauvoir, to her entry into the Parisian intellectual scene. This would work well alongside Leduc’s La Bâtarde, Genet’s plays, Beauvoir’s 1963 memoir, The Force of Circumstance, or her 1962 text Djamila Boupacha that show the politicization of sex in those years, and how the violated and sexualized body was handled in new ways by these authors. One might also pair Leduc with Fanon’s writings, as two authors on the margins who envisioned a body shaped by, and resistant to, the violence of French society. Each demonstrated that crafting a literary subject was a political act. Although Leduc often claimed she was a “desert that monologues,” her works spoke to and shaped the postwar era in ways the film, sadly, never lets us see.

Violette Leduc 1970 (reportage 1/3) by sylvainsyl

Martin Provost, Director, Violette, 2013, 139 min, Color, France, Belgium, TS Productions, France 3 Cinéma, Climax Films, Centre National du Cinéma et de L’image Animée

- These also follow in the wake of the success of Jean-Francois Richet’s 2008 celebrated two-parts film about the famed criminal Jacques Mesrine played by Vincent Cassel: Mesrine: L’Instinct de mort (1952-1972) and Mesrine: L’Ennemi Public N˚1 (1972-1979).

- Unlike the controversy that has marred the Yves Saint Laurent biopics. René de Ceccatty, Éloge de la bâtarde (Stock, 2013); Carlo Jansiti, Violette Leduc (Grasset, 1999).

- Simone de Beauvoir, préface, in Violette Leduc, La Bâtarde (Gallimard, 1964), 9, 10

- Jansiti, Violette Leduc, 199.

- In addition to her novels, the most reliable account of Leduc’s life remains, to this date, Jansiti’s biography.

- Jansiti, Violette Leduc, 372.

- Beauvoir, préface, La Bâtarde, 16, 18-19.

- http://www.npr.org/2014/07/08/329864065/violette-evokes-exasperating-self-pity-a-trait-the-french-like

- See Mark Micale’s review, “Mad Women Artists: Séraphine, Camille Claudel 1915, Aloïse” Fiction and Film for French Historians Vol. 4 #3 (December 2013).

- Jansiti, Violette Leduc, 130, 139, 80.

- Jansiti, Violette Leduc 447-48.

- On this, see Esther’s Hoffenberg’s captivating documentary, Violette Leduc ou la chasse à l’amour (2013).

- Beauvoir referred to Leduc in her letters to Nelson Algren and others as “the ugly woman” but wrote to her regularly during her 1947 American stay. Jansiti has noted how their correspondence was an extensive one and he claims that Beauvoir’s letters display much greater affection than usually assumed.

- Beauvoir, All Said and Done (Putnam, 1974), 47-52.

- Jansiti, Violette Leduc, 331-33.

- Jansiti, Violette Leduc,146-47.

- This is Jansiti’s characterization, Violette Leduc, 12.

- Readers might be surprised to learn that Leduc was friends with Sarraute in the 1950s and that Dominique Aury, who had secretly authored Histoire D’O, admired and supported her work.

- Richard Jobs, Riding The New Wave: Youth and the Rejuvenation of France after the Second World War (Stanford University Press, 2009); Sylvie Chaperon, Les Années Beauvoir, 1945-1970 (Fayard: 2000); Susan Weiner, Enfants terribles: Youth and Femininity in the Mass Media in France (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

- Rosemary Wakeman, The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958 (University of Chicago Press, 2009).

- Judith Coffin, “Historicizing the Second Sex,” French Politics, Culture, and Society Vol. 25 #3 (Winter 2007); “Beauvoir, Kinsey, and Mid-Century Sex,” French Politics, Culture, and Society Vol. 28:2 (Summer 2010).