Tyler Stovall

University of California, Berkeley

Perhaps the fiercest debate in the historiography of twentieth-century France has centered around French attitudes toward the Occupation, in particular the balance between collaboration and resistance. The assault against the myth of a France united in resistance to Nazism led by Marcel Ophuls, Robert Paxton, and others produced its own counter-narrative, one of Vichy as a national revolution grounded in the traditions of the French right. More recently social historians have sought to nuance this opposition, analyzing French public opinion and considering the complicated stances taken by ordinary people during the war that represented neither resistance nor collaboration in their purest states. At the core of this debate is the conviction that life under the Occupation provided an important window into the national identity and character of modern France.[1]

But what happens to this debate when one considers the considerable role played in the French Resistance by those who were not French citizens? Historians have long known that, for a variety of reasons, many foreigners took part in the resistance inside France against both Vichy and Nazi Germany. Foreign Jews, Spanish Republicans, antifascists from Germany, Italy, and Austria, and others joined partisan armies and took up the struggle to free France. The first division of Free French soldiers into Paris during the Liberation was in fact largely composed of Spanish Republicans. At the same time, a majority of the Free French forces led by Charles de Gaulle outside Europe consisted of colonial soldiers.[2] The presence of so many foreigners in the French Resistance, and the key role they played in liberating France, adds an important transnational perspective not just to the history of the Occupation but more generally to the nature of French identity in the modern era. Their experience calls into question interpretations of the Resistance as a moment of national unity, while at the same time offering an alternate vision of a multicultural France that constitutes a historical legacy for the postwar era.[3]

But what happens to this debate when one considers the considerable role played in the French Resistance by those who were not French citizens? Historians have long known that, for a variety of reasons, many foreigners took part in the resistance inside France against both Vichy and Nazi Germany. Foreign Jews, Spanish Republicans, antifascists from Germany, Italy, and Austria, and others joined partisan armies and took up the struggle to free France. The first division of Free French soldiers into Paris during the Liberation was in fact largely composed of Spanish Republicans. At the same time, a majority of the Free French forces led by Charles de Gaulle outside Europe consisted of colonial soldiers.[2] The presence of so many foreigners in the French Resistance, and the key role they played in liberating France, adds an important transnational perspective not just to the history of the Occupation but more generally to the nature of French identity in the modern era. Their experience calls into question interpretations of the Resistance as a moment of national unity, while at the same time offering an alternate vision of a multicultural France that constitutes a historical legacy for the postwar era.[3]

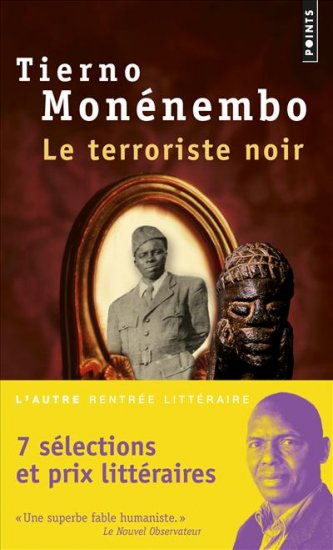

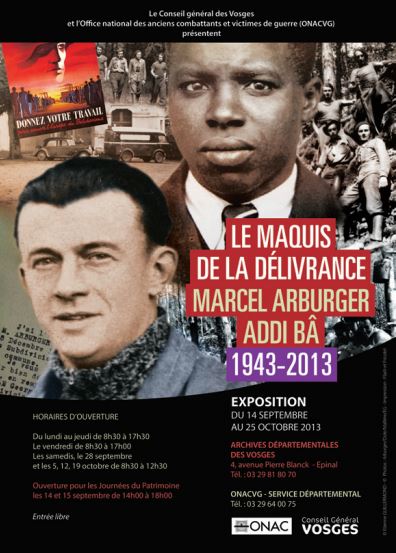

In Le terroriste noir prize-winning Guinean author Tierno Monénembo gives a fictionalized portrait of an actual African leader of the French Resistance named Addi Bâ. The novel strives to give an historically accurate portrait of this individual. Historians know relatively little about the man. Addi Bâ was born in Guinea, then a part of French West Africa, in 1916. He came to France in 1937 or 1938 as part of the family of a French tax collector stationed in Guinea, settling first in Langeais in the Touraine and then in Paris. In 1939 he joined the French Army, and was assigned to the 12th Regiment of the tirailleurs sénégalais. After the fall of France Bâ was taken prisoner by the Germans, but succeeded in escaping and made his way to the Vosges region of eastern France. There he along with other internal fugitives joined the maquis in the region. In November 1943 German forces broke up the network, arresting Bâ and many others. He was executed by firing squad on December 18.[4]

The story of Addi Bâ speaks to at least two interesting and relatively new historiographical themes in modern France. The first is the history of foreigners in the Resistance, and the view of the Resistance as a multicultural moment in twentieth century France. In particular, it raises the complex and often neglected role of colonial subjects in the struggle against Vichy. Historians have documented the presence of thousands of Africans and others from the French army in the internal resistance, yet their struggles have played little role in shaping overall views of the movement. For all the rhetoric of “a nation of 100 million Frenchmen” empowering the national struggle against Germany, a rhetoric validated by the preponderant role of colonial troops in Free French armies, the empire’s contribution to the struggle against Nazism and Vichy has rarely fit into standard narratives of the Resistance. Moreover, colonial resistance, as any perusal of an Internet search engine will demonstrate, has generally been resistance against France, not for it. It has largely been impossible, for example, for historians to integrate the Viet Minh into the history of the French Resistance. In spite of the long history of colonial armies fighting for France, a history which culminated in World War II, conceptualizing the colonial resistance within France remains a difficult task.[5]

The story of Addi Bâ speaks to at least two interesting and relatively new historiographical themes in modern France. The first is the history of foreigners in the Resistance, and the view of the Resistance as a multicultural moment in twentieth century France. In particular, it raises the complex and often neglected role of colonial subjects in the struggle against Vichy. Historians have documented the presence of thousands of Africans and others from the French army in the internal resistance, yet their struggles have played little role in shaping overall views of the movement. For all the rhetoric of “a nation of 100 million Frenchmen” empowering the national struggle against Germany, a rhetoric validated by the preponderant role of colonial troops in Free French armies, the empire’s contribution to the struggle against Nazism and Vichy has rarely fit into standard narratives of the Resistance. Moreover, colonial resistance, as any perusal of an Internet search engine will demonstrate, has generally been resistance against France, not for it. It has largely been impossible, for example, for historians to integrate the Viet Minh into the history of the French Resistance. In spite of the long history of colonial armies fighting for France, a history which culminated in World War II, conceptualizing the colonial resistance within France remains a difficult task.[5]

The other important new theme concerns the history of blacks in France. During the last decade the place of blacks from Africa and the Caribbean in French history and contemporary life has received new attention, signaled by the publication of Pap Ndiaye’s La condition noire en France. This  has been a complicated and controversial enterprise, challenged both by those who reject considering racial or other distinctions between French citizens, and by those who contend the concept of “blackness” neglects the major distinctions between those from the Caribbean and from different parts of Africa. Nonetheless, this new attention to the history of French blacks has helped rescue from historical obscurity men and women like Addi Bâ, inscribing their stories in the broader narrative of French history.[6]

has been a complicated and controversial enterprise, challenged both by those who reject considering racial or other distinctions between French citizens, and by those who contend the concept of “blackness” neglects the major distinctions between those from the Caribbean and from different parts of Africa. Nonetheless, this new attention to the history of French blacks has helped rescue from historical obscurity men and women like Addi Bâ, inscribing their stories in the broader narrative of French history.[6]

Tierno Monénembo begins Le terroriste noir with an acknowledgment of this obscurity. He dedicates his novel in part to the tirailleurs sénégalais, “living or dead,” and opens with a quotation from Léopold Senghor:

They decorate the graves with flowers, they guard the flame of the Unknown Soldier,

You, my unknown brothers, no one knows your name.

The novel is both an attempt to break this silence, and a story of how the people of the small French village who sheltered Bâ chose to remember him and that period of their lives in general.

Le terroriste noir does not present a linear biographical narrative of the life of Addi Bâ. Rather, it gradually unveils his life in the Resistance and wartime France, and by this means, his earlier history. The story takes place in Romaincourt, a fictionalized version of Tollaincourt, a tiny village in the Vosges. It is told from a variety of perspectives, but above all from that of Germaine Tergoresse, a teenager during the war who is now relating her memories to Bâ’s nephew. The French have brought him to Romaincourt to help commemorate the memory of his uncle, and during that visit Mme. Tergoresse, now eighty years old, tells him not only the story of his uncle’s wartime life in the town but also his impact on her and the other villagers he encountered. The narrative oscillates between past and present, between historical events and their memory, to give a multifaceted portrayal of the life and times of Addi Bâ.

Le terroriste noir opens in the fall of 1940 with the discovery by the people of Romaincourt that there is a black man roaming the woods near their village, an isolated area where no one had ever seen a black person before. For the man who discovers him, Bâ’s presence in their little town represents all the turmoil brought by the war, and he wants none of it: “What I want is to live without bombs, without Boches, and especially without negroes.”[7] His wife, in contrast, insists on helping out the poor man, so she finds him in the forest and arranges shelter and food for him. The first half of the novel chronicles Bâ’s clandestine existence in Romaincourt, and the growing attachment of the villagers to him. Monénembo skillfully portrays the traumas of life in occupied France. The locals’ efforts to feed Addi Bâ only underscore the lack of food in general, and the often desperate struggles to find it. Many of the villagers have lost family members, such as Huguette, whose husband was arrested by the SS after slandering German soldiers. They worry constantly about hiding Bâ from the Nazi forces who patrol the area from time to time.

Le terroriste noir opens in the fall of 1940 with the discovery by the people of Romaincourt that there is a black man roaming the woods near their village, an isolated area where no one had ever seen a black person before. For the man who discovers him, Bâ’s presence in their little town represents all the turmoil brought by the war, and he wants none of it: “What I want is to live without bombs, without Boches, and especially without negroes.”[7] His wife, in contrast, insists on helping out the poor man, so she finds him in the forest and arranges shelter and food for him. The first half of the novel chronicles Bâ’s clandestine existence in Romaincourt, and the growing attachment of the villagers to him. Monénembo skillfully portrays the traumas of life in occupied France. The locals’ efforts to feed Addi Bâ only underscore the lack of food in general, and the often desperate struggles to find it. Many of the villagers have lost family members, such as Huguette, whose husband was arrested by the SS after slandering German soldiers. They worry constantly about hiding Bâ from the Nazi forces who patrol the area from time to time.

Gradually Bâ integrates himself into the life of the community during the three years he lives there. Like many small towns, Romaincourt has its share of conflicts, including a bitter rivalry between its two most prominent families, the Tergoasse and the Rapenne. Yet as an exotic outsider Addi Bâ is able to surmount these local quarrels, at least initially. He passes time with one elderly woman in embroidery (which, he notes, is men’s work in Africa), and plays chess with a retired colonel in his mansion. He also proves very attractive sexually to a number of women in Romaincourt and the vicinity, although these affairs (like much else in his life) are hinted at rather than described in detail. For the most part Monénembo tends to let Germaine and the other villagers describe him rather than giving him his own voice. The result is an interesting transnational perspective on France, a description of a small French village by an African Francophone writer.

Bâ’s life in Romaincourt changes dramatically in 1943 when he becomes a leader of the local Resistance. Germaine notes that he gradually became more interested in listening to radio broadcasts from London, then made more and more frequent nocturnal excursions away from the town, either for Resistance activities or to visit various lovers. The last section of the novel describes Bâ’s life in the local resistance, the first organized group in the Vosges. Monénembo emphasizes the importance of the Service du Travail Obligatoire, forced labor in Germany, in enabling Bâ and his fellow militants to recruit members. He also describes the resisters’ relationship with the Free French authorities in London, and their increasing frustration at their forced inactivity and the interminable wait for an Allied invasion of France. They did take some initiatives, however, including smuggling downed Allied fighters across the border into nearby Switzerland, and helping hide Jews, notably in the Paris mosque. At one point the young Germaine asks Addi Bâ why an African would want to fight for a colonial power, and he enigmatically responds by saying the fire that burns you can also warm you. Bâ’s exploits earn him the name “The Black Terrorist” from his German opponents.

Like many resisters, Addi Bâ and his comrades did not live to see victory. In the novel the Resistance encampment is betrayed and its members arrested by the Germans. Bâ himself is caught in Romaincourt and along with his comrades imprisoned and tortured in nearby Epinal by the Gestapo before his execution in December 1943. Who betrayed him and the Resistance network to their deaths? The novel hints at several possibilities, including one of his lovers, and also suggests he may have fallen victim to the rivalry between the Tergoresse and Rapenne families. But in the end the novel, like the historical record, provides no definitive answer. It does, however, address the postwar ramifications of Bâ’s life, including his impact on Romaincourt and the decision to honor his memory by awarding him the Medal of the Resistance in 2003.

Le terroriste noir is a fascinating study of resistance and race in occupied France, skillfully written and hauntingly presented. It balances an account of the historical record, to the extent that we know it, with the construction of Addi Bâ, Germaine Tergoresse, and several others as complex, compelling individuals. It also challenges the idea of World War II as “the good war,” a simplistic binary struggle. Instead, the great conflict represents a world turned upside down, full of grey rather than black and white. As Germaine says,

What a strange moment, the war! Black resistance fighters, French traitors, Germans who love Berlioz, Baudelaire, and Beaujolais, policemen allied with outlaws. Who was the victim, who the executioner? [8]

To this one can add a story of life in France written by a Francophone African novelist. Finally, the very title of Le terroriste noir is challenging and provocative. During the war the Germans and Vichy routinely labeled French Resistance fighters terrorists. In the era of the global war on terror, when the figure of the terrorist is generally assumed to represent ultimate evil, it is useful to remember that such a conceptualization has a certain Nazi pedigree.

In Le terroriste noir Tierno Monénembo brings the histories of metropolitan and colonial France together, exploring the transnational and universal dimension of the French Resistance. He uses the novelist’s craft to illuminate a neglected aspect of French history, in all its complexity and heartbreak. He portrays Addi Bâ as a hero, certainly, but also a real human being with failings and doubts. Similarly, his French neighbors are at times generous and courageous as well as small-minded and venal. In general, this is a fine portrait of a small French village at war, and how its local life interacted with global patterns and imperatives. As an historical novel, it thus succeeds admirably in bringing to life the colonial contribution to the French Resistance, and more broadly a new vision of national identity during modern France’s darkest hour. By reframing our understanding of the Resistance around a colonial subject, Le terroriste noir forces us to rethink our ideas about what it means to be French, both during World War II and today.

In Le terroriste noir Tierno Monénembo brings the histories of metropolitan and colonial France together, exploring the transnational and universal dimension of the French Resistance. He uses the novelist’s craft to illuminate a neglected aspect of French history, in all its complexity and heartbreak. He portrays Addi Bâ as a hero, certainly, but also a real human being with failings and doubts. Similarly, his French neighbors are at times generous and courageous as well as small-minded and venal. In general, this is a fine portrait of a small French village at war, and how its local life interacted with global patterns and imperatives. As an historical novel, it thus succeeds admirably in bringing to life the colonial contribution to the French Resistance, and more broadly a new vision of national identity during modern France’s darkest hour. By reframing our understanding of the Resistance around a colonial subject, Le terroriste noir forces us to rethink our ideas about what it means to be French, both during World War II and today.

Tierno Monénembo, Le terroriste noir (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2012).

Editor’s note: An English translation is ready and forthcoming from Diasporic Africa Press, New York. A small website dedicated to Addi Bâ Mamadou: http://addiba.free.fr/galeries_photos.html

- See Julian Jackson, France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) for a useful and comprehensive overview of this debate. See also Sarah Fishman, et. al., eds., France at War: Vichy and the Historians (New York: Berg, 2000).

- Rachid Bouchareb’s 2006 film Indigènes, on North African soldiers in France during World War II, had a major impact in bringing this history back to public memory.

- On foreigners in the French Resistance see Denis Peschanski, Des étrangers dans la Résistance (Paris: Atelier, 2002); Stéphane Courtois, et. al., Le sang de l’étranger: les immigrés de la MOI dans la Résistance (Paris: Fayard, 1989).

- On the life of Addi Bâ see Etienne Guillermond, Addi Bâ, le résistant des Vosges (Paris: Editions Duboiris, 2013). He is also mentioned in Benoît Hopquin, Ces Noirs qui ont fait la France (Paris: Calman-Lévy, 2009); and Lilian Thurmam and Bernard Filaire, Mes étoiles noires (Paris: Editions Philippe Ray, 2010).

- On the tirailleurs sénégalais during World War II, see Armelle Mabon, Prisonniers de guerre “indigènes”, visages oubliés de la France occupée (Paris: La Découverte, 2010); Julien Fargattas, Les tirailleurs sénégalais. Les soldats noirs entre légendes et réalités, 1939-1945 (Paris: Taillander, 2012); Nancy Lawler, Soldiers of misfortune: Ivorien tirailleurs of World War II (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1992); Raffael Scheck, Hitler’s African victims: the German Army massacres of Black French soldiers in 1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Pap Ndiaye, La condition noire: essai sur une minorité française (Paris: Calman-Lévy, 2008); Trica Keaton et. al., Black France/France noire: the history and politics of blackness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012); Dominic Thomas, Black France: colonialism, immigration, and transnationalism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007).

- Tierno Monénembo, Le terroriste noir (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2012), 15.

- Ibid., 188.