Lisa Jane Graham

Haverford College

Diderot might have liked the latest film adaptation of La Religieuse by Guillaume Nicloux. The novel originated in 1760 as an elaborate hoax by Diderot, Grimm and Madame d’Épinay to get their friend, the marquis de Croismare, to return to Paris from a self-imposed retreat on his Normandy estate. The prank involved fake letters written by a nun on the run from the police seeking Croismare’s protection. These letters were in turn based on a real judicial case that inspired Diderot’s unfinished novel. The lack of a conclusion may explain the novel’s appeal for filmmakers who can engage with a historical text that leaves room for their own interpretation. First Jacques Rivette and now Guillaume Nicloux adapted the novel for the screen and each film reflects a distinct reading of the eighteenth century through the lens of contemporary culture. Comparing the two films to one another and to the novel allows us to explore the relationship between film and history and film and fiction in the transmission of historical knowledge.

Diderot cited the novel as one of his favorite texts and revised it obsessively until his death in 1784. Despite his efforts, the novel remains unfinished. Never one to restrain his pen, Diderot knew that the novel’s scathing portrait of religious life would never get past the royal censors. Rather than risk another stint in prison, Diderot circulated the novel clandestinely in 1780 among subscribers to the Correspondance littéraire. It was published in 1796 as part of the first complete edition of his works. A whiff of scandal has always accompanied La Religieuse from the original affair to the prank that shaped its characters and plot. The scandal continued in the twentieth century when Jacques Rivette made the first film version in 1966.

Diderot’s attachment to the novel and his inability to find a satisfactory conclusion reflected his ambivalence about the genre as an instrument of enlightenment. He wrote the novel when developing his theory of aesthetics in the Salons of the 1760s. Just as he warned readers about the dangers of morally suspect painters like Boucher, he worried that the novel was a frivolous genre that corrupted both readers and authors.[1] At the same time, given its popularity, he recognized the potential of the novel to reach large numbers of readers. Inspired by English contemporaries such as Richardson, Diderot combined medical theory and sentimental fiction to explore links between sensibility and morality.[2] Since moral improvement began with emotional engagement, Diderot created new expectations for readers (and viewers as described in the Salons) to immerse themselves in the text (or painting). According to Grimm, Diderot succeeded in La Religieuse because “you cannot read one page of this novel without shedding tears.” Beyond this pleasure of shared tears, Grimm hailed the novel as “a work of public utility” with its “cruel satire” of convent life.[3]

Like so many eighteenth-century novels, La Religieuse straddled the worlds of fiction and history. Diderot was inspired by an actual case from 1752 in which Marguerite Delamarre, a girl forced into a convent by her parents, petitioned to have her vows annulled. She hired a lawyer and circulated a mémoire that drew the attention of the real marquis de Croismare.[4] Diderot used the case as the basis for the first-person narrative of an escaped nun, the fictitious Suzanne Simonin, seeking the protection of a benefactor, the marquis de Croismare. Diderot denounced religious hypocrisy and abusive authority through Suzanne’s torments. The real Marguerite Delamarre lost her case in 1758 and remained at the Longchamp convent until it was dissolved during the French Revolution. By contrast, Diderot’s novel ends with his escaped heroine working as a laundress and living in fear of imminent arrest. Intentionally or not, Diderot left his readers wondering about Suzanne Simonin’s fate, a nice metaphor for French society in the 1780s.

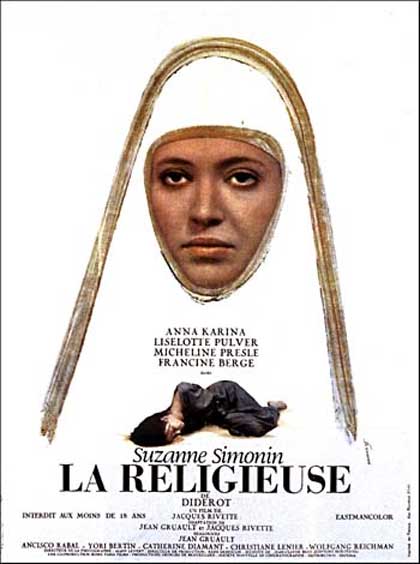

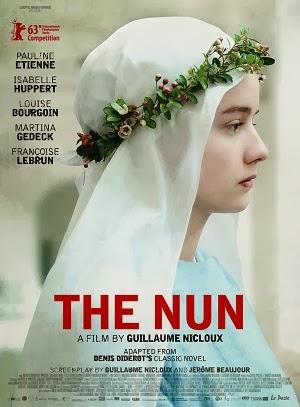

When Jacques Rivette made his film Suzanne Simonin, La Religieuse de Diderot in 1966, he saw an opportunity to attack sacred institutions, with France once more on the brink of revolt. Rivette’s film was banned as “antireligious” and could not be shown for a year after it premiered at Cannes.[5] Rivette initially asked to shoot the film at the abbey of Fontevraud but after his request was denied, he relocated to Avignon. When Guillaume Nicloux came to the project, he was refused permission to use two eighteenth-century French convents and ended up in Germany.[6] Nicloux’s film has stirred controversy, albeit of a different order than that provoked by Rivette in Gaullist France. Nicloux invented an ending that severs his film from the novel’s social context and distorts Diderot’s skepticism regarding the outcome of Suzanne’s struggle. Ironically, Rivette captured the spirit of the novel while displacing it aesthetically whereas Nicloux imposes twenty-first century assumptions within an Old Regime environment. Rivette’s film looks and feels like 1960s Paris whereas Nicloux recreates the physical world of eighteenth-century France. What are the effects of these aesthetic choices on viewers and where do they leave Diderot’s novel?

Inevitably Nicloux’s film is haunted by Rivette’s version. Rivette chose the face of French New Wave cinema, Anna Karina, to play the protagonist. Karina portrayed the sixteen-year old girl forced into a convent against her will as a twentieth-century Everywoman fighting for her autonomy in the face of repressive authorities. Filmed two years before the revolts of 1968, the film captured the swirling tides of cultural angst, feminism, and youth frustration that shook De Gaulle’s regime. Rivette remained loyal to the spirit of Diderot’s novel even though he transformed the eighteenth-century convent into a twentieth-century prison. For example, Rivette’s film opens with sounds not images: we hear fists pounding on a door and the chiming of church bells. The film’s continued use of aural effects builds a sense of menace and foreboding.

Inevitably Nicloux’s film is haunted by Rivette’s version. Rivette chose the face of French New Wave cinema, Anna Karina, to play the protagonist. Karina portrayed the sixteen-year old girl forced into a convent against her will as a twentieth-century Everywoman fighting for her autonomy in the face of repressive authorities. Filmed two years before the revolts of 1968, the film captured the swirling tides of cultural angst, feminism, and youth frustration that shook De Gaulle’s regime. Rivette remained loyal to the spirit of Diderot’s novel even though he transformed the eighteenth-century convent into a twentieth-century prison. For example, Rivette’s film opens with sounds not images: we hear fists pounding on a door and the chiming of church bells. The film’s continued use of aural effects builds a sense of menace and foreboding.

In Rivette’s film, the viewer first sees the heroine through iron bars, those that separate the nuns from the laity, but here they suggest a prison cell. Rivette works in a palette of grey and black with flashes of white. The clanking of bolts and doors alternates with the voices of children playing outside, reinforcing the carceral atmosphere. In the opening scene Suzanne refuses to take her vows and rushes forward to grasp the bars that separate her from the public. Rivette’s camera implicates the viewer in Suzanne’s appeal for her freedom just as Diderot intended. She continues calling for her release as the nuns drag her away.

For Rivette, Suzanne is the victim of a hypocritical and sexist society in which an illegitimate child must pay for her mother’s adultery. He portrays Madame Simonin as a cold and distant figure more concerned with her own salvation than her daughter’s happiness. Although Suzanne is devout, she has no calling, and therefore refuses to fulfill her mother’s plan. Suzanne is a victim but she is also a fighter who mobilizes print, public opinion, and the law to change her fate. Rivette follows the novel up to the point where Suzanne escapes with the aid of an unhappy priest, also a victim of parental tyranny, who assaults her as soon as they are alone. Rivette paints a bleak portrait of Suzanne’s options outside the convent: she must hide from the police and sell her body to survive. The brothel becomes the secular equivalent of the convent depriving Suzanne of agency and, worse, of spiritual solace. In the last scene, she kills herself by jumping out of a window. The final shot of Suzanne dead on the pavement, a ghostly white figure face down on a dark screen, transforms her into a martyr for a generation trapped in a stultifying society. Rivette’s decision to end with Suzanne’s suicide offers a pessimistic interpretation of Diderot’s novel and the possibility of freedom.

Fifty years after Rivette, Guillaume Nicloux gives us a Religieuse for the twenty-first century. Nicloux recalls reading Diderot’s novel as an adolescent and the profound impact it had on him. His background making polars influences his techniques and sensibility. In an interview with Télérama, Nicloux explains that in re-reading the novel to prepare for the film, he was drawn both to the heroine’s story and the “carceral universe” in which it unfolds.[7]The film conveys this vision by attending both to the psychology of characters and the physical effects of climate. The camera sweeps across bleak landscapes and chilly cells as it follows the nuns through the daily rituals of labor and prayer. The film’s pace is deliberately slow, capturing the monotony and discipline of cloistered life. Nicloux tries his viewer’s patience by emphasizing ambience and experience over plot. The pace drags at times despite the lush soundtrack of period music that reminds us of Suzanne’s inner life, her need to be free and see the world. She has musical talent, a lovely voice that connects her to society and adds value to her presence in the convent. Just like Diderot in his narrative, Nicloux uses music as a leitmotif. Music is an activity that arouses the passions and bypasses reason: the key seduction scenes in the text occur when Suzanne is playing or singing at the harpsichord. Diderot believed that music stimulates the senses, evoking spiritual impulses and carnal desires.

Unlike Rivette who focused on the anti-Catholicism of the novel, Nicloux sees religion itself as repressive. His film veers from Diderot’s novel to offer an “ode to liberty” in which the individual spirit triumphs over a repressive society. Nicloux wrote the screenplay with Jérôme Beaujour and the script hews closely to the novel, lifting some of its scenes directly from the text. Cinematography communicates the texture and feel of the period. The film was shot in natural light to recreate life before the age of electricity or indoor heating. Close-shots of people’s faces display the effects of climate such as red noses and cheeks chafed by the cold air. The film uses a palette of greys contrasted with the piercing blue eyes of the heroine played by the gifted young Belgian actress, Pauline Étienne.The interior scenes are illuminated by fire, candles, or moonlight. The somber lighting and harsh climate reinforce the noir atmosphere of the story, expressing Suzanne’s struggle to grope her way out of darkness toward the light of liberty. It is a visually moving film.

Unlike Rivette who focused on the anti-Catholicism of the novel, Nicloux sees religion itself as repressive. His film veers from Diderot’s novel to offer an “ode to liberty” in which the individual spirit triumphs over a repressive society. Nicloux wrote the screenplay with Jérôme Beaujour and the script hews closely to the novel, lifting some of its scenes directly from the text. Cinematography communicates the texture and feel of the period. The film was shot in natural light to recreate life before the age of electricity or indoor heating. Close-shots of people’s faces display the effects of climate such as red noses and cheeks chafed by the cold air. The film uses a palette of greys contrasted with the piercing blue eyes of the heroine played by the gifted young Belgian actress, Pauline Étienne.The interior scenes are illuminated by fire, candles, or moonlight. The somber lighting and harsh climate reinforce the noir atmosphere of the story, expressing Suzanne’s struggle to grope her way out of darkness toward the light of liberty. It is a visually moving film.

Nicloux claims that he wanted to make Diderot’s heroine more than a victim by granting her more agency. One senses her resilience in the face of oppression when she decides to take up pen and paper to appeal for her freedom. The film does an excellent job highlighting print as the heroine’s weapon against the regime that oppresses her. Nicloux begins with Suzanne’s mémoire, discovered by a young nobleman on his trip home to visit his dying father. The film implies some mysterious link between the father, the son, and the author of the mémoire. Altogether, Nicloux captures the novel’s emphasis on print as the conduit to the outside world and the site of self-formation. The power of the convent resides in its secrecy and conformity. Later in the film, we see Suzanne risking her safety to steal the rationed paper and ink that offer her only hope of escape. She is quickly punished for this transgression after being strip-searched in her room, a scene that recalls both twentieth-century dissidents and eighteenth-century philosophes forced to hide manuscripts in mattresses or chair cushions. Some of these scenes could be used effectively in the classroom –to recreate the rituals and intrigues of convent life as well as the power of the pen to mobilize the law and public opinion. What troubled me most about Nicloux’s Suzanne, however, is that she is shown in a horizontal position for much of the film, lying in bed, weeping on a cold floor, and literally becoming a floor when forced to lie face down as the nuns walk over her on their way to mass. It is hard to see her resilience when she is constantly laid low. In addition, her eyes are rimmed with tears in most shots, turning Diderot’s feisty and coquettish heroine into a weepy victim of her society.

The most controversial part of Nicloux’s film is his radical rewriting of the conclusion. The happy ending may satisfy twenty-first century viewers but dismayed this dix-huitièmiste. I don’t mind the fact that Nicloux altered the story –a film is not obliged to mirror its source– but I am bothered by how he changed it. By choosing to add “une dimension romanesque” to the story, he makes Suzanne’s search to find her biological father the motor of her desire for freedom. The film recounts a girl’s hunt for her father in a society where without a legitimate father one has no civil status.[8] In Nicloux’s film, Madame Simonin is a loving mother torn between her duty and her heart. She evokes the affair that produced Suzanne with palpable nostalgia for a man who was far more appealing than her husband. Nicloux suggests that Suzanne’s mother is also a victim of her society, trapped in a loveless marriage and obliged by her adulterous transgression to obey her husband. Nicloux turns the original target of Diderot’s prank, the marquis de Croismare, into Suzanne’s biological father. Her lawyer Monsieur Manouri dies in the novel, but here becomes Croismare’s agent who organizes her escape. Rather than finding herself in a dingy coach with a lascivious priest who assaults her, Suzanne is accompanied by a kindly surrogate father who brings her home just in time to meet her biological father whose days are numbered. In this reading, her liberty depends on her father’s desire to recognize his illegitimate daughter. Nicloux transforms the absent rake of the novel into a gruff but tender father worthy of a Greuze painting. Although Diderot admired Greuze, he knew that the stigma attached to illegitimate children virtually eliminated the possibility of a happy reunion.

Nicloux prefers this ending to Rivette’s because suicide represents a betrayal of Diderot’s celebration of resistance to despotism. According to him, Suzanne deserves to enjoy her liberty. In the last shot, Suzanne stands tall on the terrace of a chateau, blinking in the sunlight as she gazes out on the gardens that extend before her. She is not alone. This new world grants her more than freedom. By finding her father, she has acquired a half-brother and an inheritance, a family and an estate. Yet this happy ending rings false in the context of Old Regime society where such outcomes remained the stuff of sentimental fiction not fact. Although Olympe de Gouges summoned parents to recognize their offspring in her Declaration des Droits de la Femme et des Citoyennes, such calls would take a long time to be enacted into law.[9] One might use Nicloux’s film to stimulate class discussions about why his ending makes no historical sense and the implications of his choice to revive the Family Romance.[10]

The film asks us to consider where we locate historical authenticity: in material attributes such as costume and light or the social constraints of patriarchy and illegitimacy that structured the period. Diderot intentionally left the fate of Suzanne hanging because he was unsure in 1782 whether the forces of light would triumph over those of darkness. The social norms of Old Regime France did not support the right of individuals to choose their mates, their professions, their religion, to name a few of the things we take for granted today. Children and women were especially disadvantaged by a legal system designed to protect patriarchy, lineage, and the transmission of property. Even though the French Revolution swept away the privileges and hierarchy of the Old Regime and weakened the role of the church, it did not usher in an era of sexual or social equality. Most illegitimate children did not discover that they were the scions of noble families as one reads in fairy tales. The fact that Diderot failed to conclude his novel suggests that the problems of social conformity and sexual hypocrisy resisted neat solutions like the one offered by Nicloux.

Moreover, Nicloux’s ending erodes the agency of Diderot’s heroine by making her fate depend on men like Manouri and Croismare. The women in the film are sadistic, depraved, superficial, or submissive. Diderot’s novel raised a serious question about the plight of women on the cusp of the modern era: what were their options in a world without fathers to control or protect them? His novel is more troubling than Nicloux’s film, which evokes this oppressive society but dismisses its constraints. Nicloux makes women’s subjectivity depend on paternity whereas Diderot imagined a world in which men and women were no longer docile royal subjects but not yet citizens. Refusing Diderot’s ambivalence, Nicloux’s film suggests that we have found the ending that eluded him. Such complacenc, while reassuring, is misleading because it suggests that the struggle of Diderot’s heroine is safely behind her. This might well be open to question.

Jacques Rivette, Director, Suzanne Simonin, la religieuse de Diderot (The Nun) (1966) France/Color, Rome Paris Films, Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC), 135 min.

Guillaume Nicloux, Director, La Religieuse (The Nun) (2013), France, Germany, Belgium/Color, Les Films du Worso, Belle Epoque Films, Versus Production, 112 min.

- The classic account of the debates about the novel in eighteenth-century France is Georges May, Le dilemme du roman au XVIIIe siècle ((Paris: PUF, 1963). More recent discussions include, Joan DeJean, Ancients against Moderns: Culture Wars and the making of a Fin de Siècle (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997) and Thomas Kavanagh, Enlightened Pleasures: Eighteenth-Century France and the New Epicureanism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

- Anne C. Vila, Enlightenment and Pathology. Sensibility in the Literature and Medicine of Eighteenth-Century France (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), pp. 152-181.

- “Préface du précédant ouvrage tirée de la Correspondance littéraire de M Grimm, année 1760″ in Denis Diderot, La Religieuse, edited by Florence Lotterie (Paris: Flammarion, 2009), p. 198. Lotterie explains the complicated history of this preface which first appeared in 1770 in the Correspondance and later as a postface to the first published version in 1796, see her introduction, pp. vi-viii and li-liii.

- For a discussion of the Delamarre case and Diderot’s novel, see Georges May, Diderot et la Religieuse (Yale University Press/Paris, PUF, 1954), esp. pp. 47-76.

- Jacques Rivette, Suzanne Simonin, La Religieuse de Diderot, 1966. Rivette had originally titled his film La Religieuse, but modified it in the wake of the controversy that led the government to ban it for a year after it was shown at Cannes. The new title emphasized that the film was based on a novel and offered a fictional portrait of convent life.

- Sophie Grassin summarizes the two films in her article, “La Religieuse, histoire d’une adaptation hautement inflammable: sommaire des controverses,” Le Nouvel Observateur (21 mars 2013).

- Mathilde Blottière. “Guillaume Nicloux: ‘La Religieuse’, c’est une ode à la liberté”, Télérama (21 mars 2013). Entretien avec Guillaume Nicloux.

- For a discussion of the laws concerning illegitimate children in Old Regime France, see Suzanne Desan, The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004) and Matthew Gerber, Bastards: politics, family and law in early modern France (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- In the above, Desan traces the long history of paternity suits in France from the Old Regime to the Napoleonic Code.

- Lynn Hunt applied the Freudian terminology to her analysis of the French Revolution in The Family Romance of the French Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992). This fantasy in which bastards believe that their birth parents are wealthy and noble is integral to the development of the novel according to Marthe Robert, Origins of the Novel, translated by Sacha Rabinovitch (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), pp. 21-48; first published in French as Roman des origines et origines du roman (Paris: Grasset, 1972).