Liana Vardi

University at Buffalo, SUNY

The opening scene of Un Français sets the tone. Three skinheads are pursuing a bunch of Nanterre students squatting in a field, screaming that France has no room for fags or reds. They beat one of them with a studded belt and kick him in the stomach. Pleased with themselves, they humiliate a passer-by who has accidentally knocked into one of them, and then, smirking, enter a café determined to cause trouble, threatening the barman with a meat cleaver while harassing a group of elderly Arabs. All in all a good afternoon for the brotherhood.

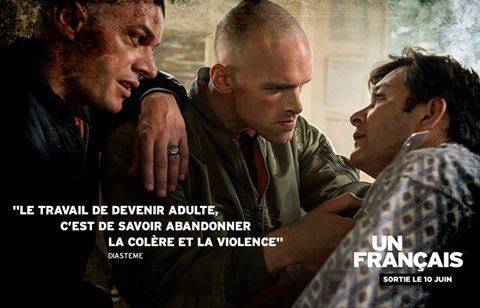

Although we will follow Braguette (Samuel Jouy), Grand-Guy (Paul Hamy), and Marvin (Olivier Chenille) over the next three decades, the main character is Marco played to perfection by Alban Lenoir. Whatever reservations they might have had about the film, all reviewers agreed about his remarkable performance and the supporting cast is just as good. Marco resents his life, his alcoholic father and helpless mother, and finds refuge in his gang of neo-Nazis. He will remain loyal to them, or at least two of them, bound by a friendship that transcends political alignment.

The year is 1985, the Socialists are in power (although losing support), and Jean-Marie Le Pen’s far right party, the Front national, is emerging as a political contender, winning several local elections and sending deputies to the European Parliament. Skinheads of various stripe, including neo-Nazis, oscillate between support of the party and extra-parliamentary violence, viewing the latter as a legitimate political tool, as had their predecessors in the 1930s. Skinhead gangs were small, divided into feuding clans, and made little political impact aside from forcing the Front national to dissociate themselves from them.[1]

French Blood / Un Français (2015) – Trailer French by inference

The film, while never explicitly situating the neo-Nazis does show them helping the Front national. Thus one night, while Carlo and his buddies are covering up socialist posters with anti-Mitterrand propaganda, Punks from the anti-fascist gang, the Redskins, attack them and Marco is slightly wounded. He is annoyed at the fuss that his friends make over him at their headquarters, a neo-Nazi café. He can’t brood too long, because just as he wipes the blood of his forehead, he is summoned outside because they are under attack. A truck with rival gang members holding shotguns has appeared and hit two of his comrades. Braguette has been shot in the leg and another in the face. We get a hint of Marco’s “nature” as he feels nauseous at the sight of the buddy’s bloodied face. But the consequences of violence have yet to sink in. He runs into a Redskin on the street, who accuses the neo-Nazis of giving skinheads a bad name, and Marco beats him to a pulp. He is arrested in a nearby café and upon his release (the other man is hurt but not dead and the police don’t have time to waste on gang-related assaults), he is agitated and looking for an outlet. He sits menacingly on the bus, fidgety with hatred, and shouts abuse at an Arab family who find it safer to get off. But all is not well with him as he has a panic attack and staggers to a pharmacy where he finds a sympathetic welcome, although just the sight of him scares another client.

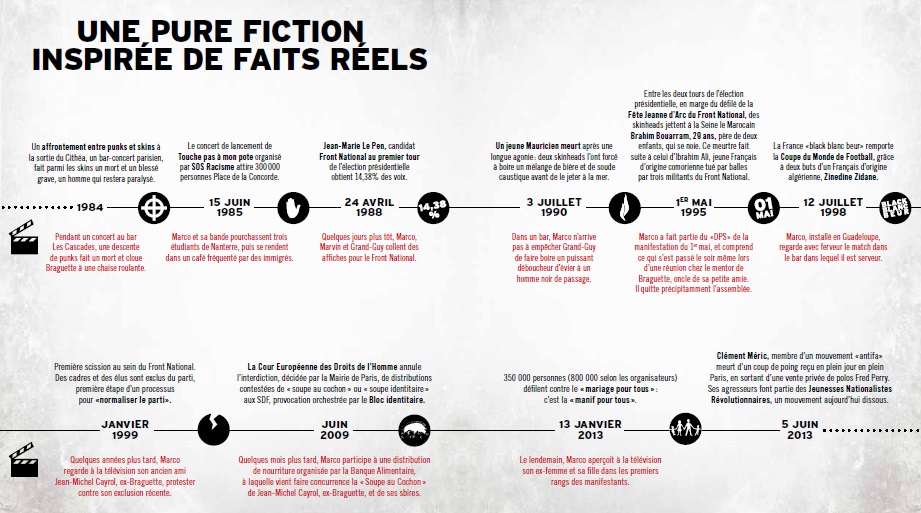

Several years later, using his only skilll, Marco has become a bouncer at a club run by an Arab and seems to have shed some of his racism. A gangster (so it would seem), rebuffed as he attempts to crash in on a private party, knifes him in the stomach. The pharmacist shows up at the hospital (Marco had apparently given his name to the police) and they become friends. He will be a humanizing influence. Meanwhile, and this is the point of this segment, Braguette, now in a wheelchair, has become a rising extreme-right spokesman, and member of the Front national.[2] Marco acts as his bodyguard. Open meetings of the “movement” being often banned by mayors, Braguette, now as the more respectable and well-dressed Jean-Michel Caproil, addresses crowds of well-to-do supporters in his sponsor’s château. Grand-Guy, Marvin, and Kiki also attend but, as they horseplay in the garden, are kicked off the premises. Marco, on the other hand, meets the château-owner’s niece, Corinne, and they hook up (and later marry). While the gang and Corinne are having drinks later that evening at their fascist bar, a drunken black man is shoved through the door and Grand-Guy forces a beer down his throat. When he fills the glass with liquid cleanser, Marco tries in vain to stop him, but the man dies. This is based on a real event, just like others that follow. To emphasize the point, the distributor Mars Films offered a guide to the chronology of events on its twitter page.

In 1995 the murders of a Comorian and a Moroccan by FN thugs are brushed off by Jean-Marie Le Pen in his Feast of Joan of Arc, 1 May broadcast. In a swanky drawing-room, Jean-Michel and his supporters follow the event on TV, toast the murderers, and sing the Marseillaise. Marco looks on, unable to join in. Jean-Michel tells Marvin –now a drug-addict still in skinhead attire—that he shames him by his infantile behaviour and that he doesn’t want him around anymore. The FN is cleaning up some of its act. But it is Marco who leaves, hyperventilating, to Corinne’s surprise. Next scene finds them in Guadeloupe where Marco is working as a waiter. It is the 1996 World Cup final and he wants his wife and one-year-old daughter to witness this great victory for France. Corinne refuses, saying that it is not a French victory but one for Algeria and Cameroon, and they argue. She calls him a coward as he refuses to hit her. They part and he loses access to his daughter.

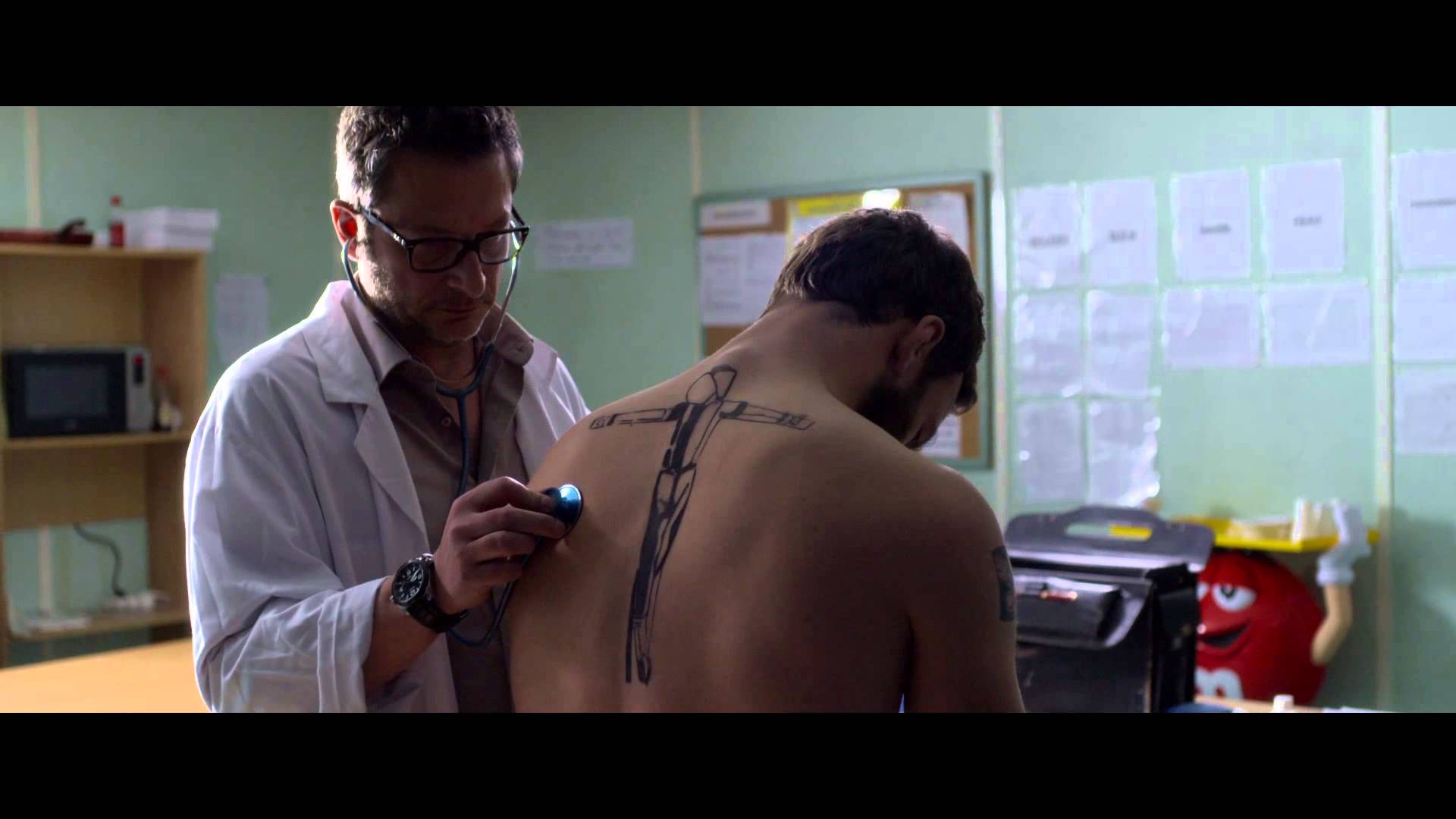

It is four years later and back in France Marco visits Grand-Guy who is serving his sentence for murdering the African, repeating that it was all a joke. Not funny, Marco replies. Grand-Guy is nostalgic about the old days when they used to beat up people. Marc is non-committal, but when his old comrade begins to rant against his fellow inmates as just a bunch of fags and bougnoules [niggers], Marco sees him as mentally deranged. Grand-Guy is dragged away by the guards, foaming at the mouth. At his annual check-up Marco’s doctor suggests, yet again, that he get his back tattoo removed by laser, remonstrating with him “you aren’t going to live with this all your life, are you?” Marco walks away. He is now working at a hypermarché and, through a fellow worker, gets involved with charitable food donations. Time passes. Jean-Michel is kicked off the Front national central committee for refusing to disavow his racist past. Marvin is dying of cancer, Kiki by his side.

Marco has learned to control his anger. The pharmacist taught him to take deep breaths when he gets upset, while his (pro bono) lawyer has advised him to wait for his daughter to grow up (she is by now a teen-ager) so that he might reconnect with her, despite her mother’s brainwashing. He volunteers at the soup kitchen set up by the same female co-worker. An unrepentant Jean-Michel shows up with his goons, setting up a table so that, in a media stunt, he can offer the immigrants a good old French pork soup [prescient of the current cantine debate]. He spots Marco and calls him a traitor who should be shot. While all Marco asks is that he leave them alone, as a personal favour, Jean-Michel head-butts and punches him and he falls to the ground. There are too many witnesses to maul him any further Jean-Michel declares as he and his ruffians leave the premises. In a last scene, having lost his mother, Marco is preparing dinner in his apartment watching the 2013 pro-family rally at the Eiffel Tower as a column of radical extremists, who have not been invited, join the cortege Among them, he spots his daughter.

Marco has learned to control his anger. The pharmacist taught him to take deep breaths when he gets upset, while his (pro bono) lawyer has advised him to wait for his daughter to grow up (she is by now a teen-ager) so that he might reconnect with her, despite her mother’s brainwashing. He volunteers at the soup kitchen set up by the same female co-worker. An unrepentant Jean-Michel shows up with his goons, setting up a table so that, in a media stunt, he can offer the immigrants a good old French pork soup [prescient of the current cantine debate]. He spots Marco and calls him a traitor who should be shot. While all Marco asks is that he leave them alone, as a personal favour, Jean-Michel head-butts and punches him and he falls to the ground. There are too many witnesses to maul him any further Jean-Michel declares as he and his ruffians leave the premises. In a last scene, having lost his mother, Marco is preparing dinner in his apartment watching the 2013 pro-family rally at the Eiffel Tower as a column of radical extremists, who have not been invited, join the cortege Among them, he spots his daughter.

Patrick Asté, known as Diastème, is a musician, journalist, novelist, scriptwriter and director of two films. The second, Un Français, was controversial and, for fear of ultra-nationalist reprisals, opened in far fewer theatres than originally agreed.[3] I missed seeing the movie in Paris and put it on my Toronto film festival list. To my surprise, I found it much better than I’d expected. There had been some enthusiastic reviews, but several accused the director of naïveté and didacticism in his treatment of the hero’s redemption. Whether he is successful in conveying this message comes down to whether one accepts the gradual transformation that I described above. When we first meet Marco he is a brute who, like his buddies, simply enjoys hurting people. The film follows him over three decades from bouncer, bodyguard to a far-right activist, waiter, to supermarket worker. Toward the end, he takes care of his aged mother in his childhood flat, and keeps to himself. Over time, he has grown sick of violence, has come to view immigrants as just people, and his former friends as bullies preying on the weak. They remain unrepentant. Marvin may no longer be violent, but he is still a skinhead; Grand-Guy remains a violent homophobic racist, just like Braguette (Jean-Michel). Amidst this, the director wants to show us a sincere and profound rejection of violence by a former skinhead, who, moreover, distances himself from politics altogether.

It is not amiss to wonder what the film is really about. It questions the sincerity of the Front national’s repeated efforts to dissociate itself from radical nationalists who espouse violence and “give the party a bad name.” It also queries whether there is link between youthful “hooliganism” and subsequent political engagement. To put it another way, is the extreme-right just another form of youthful thuggery, exhibiting the same rage? Le Pen’s voters are predominantly young and male. But Marco follows a different path. We encounter him when he is already a neo-Nazi, so we never fully understand the source of his or his friends’ commitment, even if we witness their rage. Friendship is key here, and when not bashing heads, the four guys resemble any other teenagers. The unease with violence, the reluctance to use his fists against defenceless immigrants, become for Marco (and the director) a deeper psychological issue: he must quell the anger inside him. So we ask is this a film about becoming a “responsible adult,” as Diastème puts it, or is it about the nastiness of Front national politics?

Were it to be used in class, it could certainly lead to interesting discussions. However, the politics behind the skinhead movement and the Front national would need to be explained because the film takes both for granted. Punk music so central to both fascist skinhead and their anti-fascist opponents plays barely a role in the film. A showing of Marc-Aurèle Vecchione’s 2008 documentary Antifa, chasseurs de skins would come in useful. Although it came out on French DVD, it does not seem to be readily available. It can, however, be accessed with English subtitles on archive.org or YouTube.

Diastème, Director, Un Français [French Blood], 2015, Color, 98 minutes, France, Mars Films

NOTES

- See Éric Rossi, Jeunesse française des années 80-90: la tentation néo-nazie (Paris, 1995). Rossi was himself a Nazi skinhead in the 1980s, expelled from the Front national for his support of violent action. He then belonged for several years to Serge Ayoub’s skinhead group Klan. In the early 1990s, he decided to go “legit” by becoming a right-wing journalist, editor of Réfléchir & Agir, a far-right publication. In the book, drawn from his MA thesis, he argues, based on case studies, that violent skinheads either left the movement after a few years or, like himself, turned to organized politics, some as members of the Front national, some not. On Rossi, see REFLEXes “Gros plan sur Éric Rossi,” 21 January 2003.

- I relied for the background on the Front national on James G. Shields, The Extreme Right in France: from Pétain to Le Pen, (London, New York, 2007). There is, of course, a mountain of books on the party both in English and French. I found this Le Monde article useful as well.

- See the reports in Le Figaro and on the BBC. Les Inrocks actively championed the film.