A Word from the Editor

This issue offers three assessments of Pierre Schoeller’s 2018 film on the French Revolution, Un peuple et son roi [One Nation, One King]. The movie opened in Paris at the end of September 2018, drawing enthusiastic endorsements from some historians and film reviewers and criticisms from others. The first since Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise (1939) to treat the Revolution from below, Schoeller privileges the people over the Court, making working-class Parisian women pivotal to the struggle for equality. Marie Antoinette, meanwhile, is a shadowy figure, consort to a Louis XVI laden with anxiety. Historians of the period, Peter McPhee, Jack and Jane Censer, and Janine Lanza offer three takes, with diminishing degrees of enthusiasm. Are the film’s omissions insurmountable or do they provide ground for discussion? All point out how the film might be used in teaching. As I write on this 25 April 2019, the film has not yet been released in the United States. A subtitled region 2 DVD is however available from the UK, and, of course in French only from France. The trailer, embedded in the middle of the second review, will give you a sense of the film’s élan.

Liana Vardi

University at Buffalo, SUNY

I. Un peuple et son roi [One Nation, One King] 2018

Peter McPhee

University of Melbourne

How can a two-hour film possibly capture something as complex as the French Revolution? The more successful attempts in recent decades have taken a single episode and teased it out in some depth: so La Nuit de Varennes created a fictitious, delightful group of characters whose coach followed the royal flight in June 1791 and Danton probed the deadly political dance of Robespierre and Danton in early 1794. But Pierre Schoeller’s Un people et son roi is far more ambitious, seeking to tell the story of Louis and the Revolution from April 1789 to Louis’ execution on 21 January 1793 through the experiences of a household of Parisian artisans, with a love story at the core.

Some will feel that the film does not quite work on a cinematic level. Trying to weave the story of Basile, a homeless orphan and petty criminal from the countryside, who joins the cortège escorting Louis back to Paris from Varennes in June 1791, where he finds love, fatherhood and a new career at the same time that the French Revolution unfolds, is perhaps a leap too far. The sans-culottes family in the faubourg Saint-Antoine at the heart of the action is rather too welcoming to Basile, too prosperous and attractive to be believable, even if so much of what they say and do rings true. Basile and Françoise, a young laundrywoman, fall in love – and make love – rather too predictably. The male head of the family, “Uncle”, is a master glass-blower and everyman’s ideal of the patriotic and loveable sans-culotte. He is initially sceptical at the time of the seizing of the Bastille – “all they’ve done is release seven poor souls” – but he then becomes a wise sans-culottes militant. Blinded in the fighting on 10 August 1792, he passes on his skills and business to Basile.

Some will feel that the film does not quite work on a cinematic level. Trying to weave the story of Basile, a homeless orphan and petty criminal from the countryside, who joins the cortège escorting Louis back to Paris from Varennes in June 1791, where he finds love, fatherhood and a new career at the same time that the French Revolution unfolds, is perhaps a leap too far. The sans-culottes family in the faubourg Saint-Antoine at the heart of the action is rather too welcoming to Basile, too prosperous and attractive to be believable, even if so much of what they say and do rings true. Basile and Françoise, a young laundrywoman, fall in love – and make love – rather too predictably. The male head of the family, “Uncle”, is a master glass-blower and everyman’s ideal of the patriotic and loveable sans-culotte. He is initially sceptical at the time of the seizing of the Bastille – “all they’ve done is release seven poor souls” – but he then becomes a wise sans-culottes militant. Blinded in the fighting on 10 August 1792, he passes on his skills and business to Basile.

Nevertheless, this is an outstanding film in many other ways. Schoeller and his crew have gone to extraordinary lengths to recreate the textures of late-eighteenth century Paris and to retell the key Parisian events of 1789-93 in a way that respects the escalating diversity of action and opinion about Louis XVI. He has assembled a superb cast, in which the stellar performances include those of Laurent Lafitte as Louis XVI, Denis Lavant as Jean-Paul Marat, Céline Sallette as Reine Audu and Olivier Gourmet as “Uncle.”

The most important point to make about this film is that it respects history and respects its audience. The film is predicated on the view that those that see it have a right to a creative work that seeks to present the past as accurately as possible. This is hardly surprising given the historical advisers who offered their expertise: Timothy Tackett, Arlette Farge, Guillaume Mazeau and Sophie Wahnich. Such is the ambition of Schoeller’s project that a good deal of background knowledge has to be assumed: there is no attempt, for example, to even hint at the reasons why the beleaguered Louis had called the Estates-General in the first place. Indeed, the Estates-General are not even mentioned: instead, we are simply presented with the National Assembly as “the first National Assembly of France.” The film leaps from the washing of the children’s feet to the taking of the Bastille to the October Days.

http://www.frenetic.ch/files/unpeupleetsonroi-dossier-pedagogique.pdf

It is superbly and sumptuously produced, from an engrossing opening scene on Holy Thursday 1789 to the closing scene where a small girl wipes some of Louis’ blood from a drum on 21 January 1793. Some critics have derided it as both too politically correct and “bum numbing” in its relentless historical narrative. But it is a very successful film in its detail and veracity and offers teachers a precious resource: it is studded with “teachable moments.” Students will love it.

One of the great highlights is the scene of a patriotic priest preaching the virtues of the new regime to his puzzled congregation in 1790 before blessing a liberty tree. The contrast is telling with the scene from another church, this one in Paris in August 1792, now a political club where sans-culottes debate the fate of the monarchy. At the same time, the absence of a powerful clerical (or noble) voice articulating the traditional role of the king as defender of the faith is the film’s greatest historical gap.

There are some delightfully acute moments produced by Schoeller. Even if Robespierre’s frail physique and thin voice are not quite captured in Louis Garrel’s superb portrayal, we have his striped jacket and his fastidious wig and references to the initial confusion about his name. As he makes his mark in 1789, listeners wonder aloud whether his name is spelled Robertpierre, Robesse-Pierre or Roberspierre – as indeed they did at the time. When Robespierre turned his attention to writing journalism in 1791-92, we even have the recreation of his distinctive handwriting, which his enemies liked to describe as the scratching of a cat’s claws.

There is an excellent scene of women fighting after the king’s execution as Jacobin sans-jupons physically attack a furious defender of king and church. Elsewhere in the film there is too little violent dissension, undermining the dramatic tension. But women are at centre stage in crowd action, and there are references to debates about their voting rights. There is a powerful interrogation scene when Françoise is arrested after the Champ de Mars protests and killings, recalling that of Constance Evrard reproduced in George Rudé’s Crowd in the French Revolution.

A whole series of class discussions could be prompted by specific details in the film. Why would Louis XVI be washing the feet of poor children on Maundy Thursday 1789? What does this say about his role within the Church? Why would Françoise be shocked to see a ‘V’ burnt into Basile’s shoulder? How do we make sense of them calling their baby Marie-Pique-Égalité? Why would an assistant tie a stone around Françoise’s leg just before she gave birth? And why would Françoise rub ash into her hair?

There are some nice moments of symbolism which would also make for lively class discussion. One is of the sun entering a street in the faubourg Saint-Antoine as the Bastille is demolished. Another is of the nightmare of a desperate, terrified Louis XVI as Louis XI, Louis XIV and Henri IV mock and chastise him for his vacillation.

More than a dozen songs from the period are dotted through the film, an invitation to students to track down those and others. The world of skilled manual work is also expertly evoked, from glass-blowing to washing clothes in the Seine (here rather too clean).

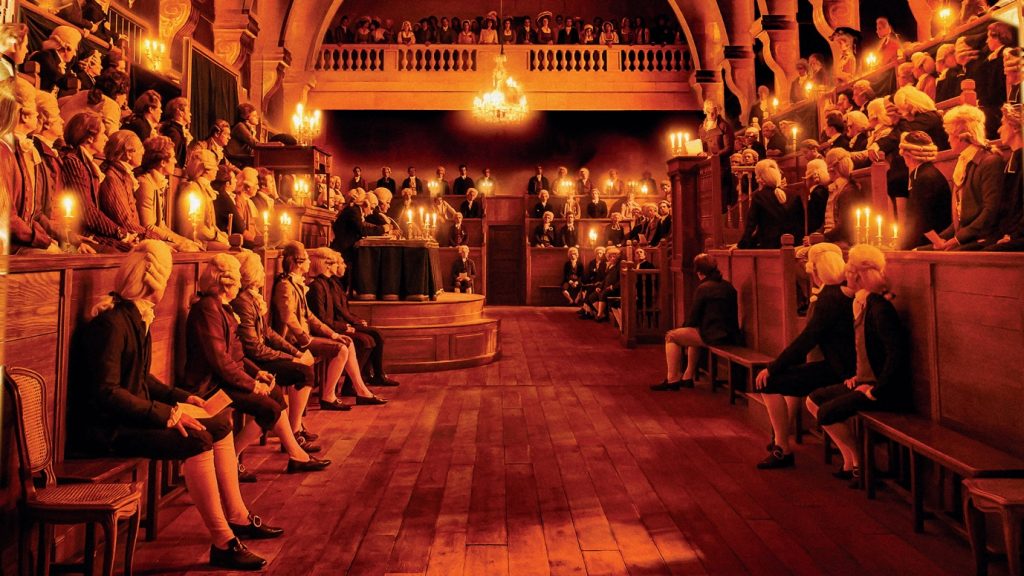

A highlight is the use of extracts from actual debates at key moments, for example, Barnave’s famous insistence to the National Assembly on 15 July 1791 that “the Revolution is over … all men are equal”. The Manège is wonderfully recreated, although not its background noise and poor acoustics. In the debate over the king’s fate there are well-chosen short quotes from many, including Orléans, Sieyès, Condorcet, Desmoulins, Danton, St-Just and Robespierre, although none of the Girondin speeches refer to the defence of the king’s life guaranteed in the Constitution of 1791, giving the impression that the Girondins were just gentler men than their tough Jacobin opponents.

The crowd scenes are mostly set on the margins of the action (such as those showing the wounded on 14 July rather than the fighting itself) but Schoeller does not flinch from recreating the violence at the Champ de Mars in July 1791 or the slaughter of the Swiss guards on 10 August 1792, although the massacres of the following September are skipped. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the common people of Paris as presented here are remarkably young, well-fed and attractive, with sets of strong white teeth. Even Louis XVI is in good shape, and only slightly plump.

At the same time, the story of the Revolution itself inevitably leaves out references to so much else of importance. In particular, there is silence about the most important social changes of the period, especially the abolition of the seigneurial system and of noble and Catholic Church privileges. Given the emphasis properly given here to the role of women in the Revolution, an opportunity is missed to refer to the introduction of divorce and partible inheritance laws which were of direct and substantial benefit to them. There is no reference to the decree of 4-11 August 1789. Indeed, rural France is virtually absent from the film. We don’t have a glimpse of the elections which studded these years, even though women discuss the vote. The magnitude of social change would have been far more convincing had the film referred to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the abolition of noble privilege.

It is important to recall the title of the film, however: this is a study of the relationship between Louis XVI and the people of Paris, not a history of the French Revolution. That is why it ends on 21 January 1793. In this light, a great strength of the film is that it does not present a unilinear view of inexorable popular disenchantment with Louis after 1789. This is a film which is aware of complicity and division: not only are the two great debates after Louis’ flight in June 1791 and on his fate in January 1793 brilliantly captured, but there are references to divisions among the sans-culottes and a confronting scuffle between women on the street. Confusion and conflict about Louis is well portrayed, even down to the eerie silence as he and his family re-entered Paris in disgrace on their return from Varennes. Patriotic Basile boasts to Françoise after their love-making that the King had blessed him

by touching his head as the royal family were brought back from Varennes, to which the equally militant Françoise responds by producing a hidden handkerchief that had once belonged to Marie-Antoinette.

The crowd scenes are powerful, notably those at the Champ de Mars in July 1791 and the Tuileries in August 1792, yet they are not chaotic or large enough despite the hundreds of extras. The crowds are presented as impelled by uplifting notions of liberty and increasing suspicion of the king and his court. There are brief references to Françoise’s first child dying of hunger in 1789, to the hungry feeling like they have stones in their bellies, but the film fails to capture the bedrock of hunger, rage and fear which fuelled crowd action. In the end, the film privileges Parisian debates about popular sovereignty and the fate of the king rather than the Revolution as a time of social upheaval, fear and civil war. The intense relationship between the king in his people is the heart of this brilliant film, but the fraught collapse of that relationship makes less sense without the wider context of a national and international crisis.

Pierre Schoeller, Director, One Nation, One King (Un peuple et son roi), 2018, 121 min, color, France, Belgium, Archipel 35, StudioCanal, France 3 Cinéma, Les Films du Fleuve.

**********

II. One Nation, One King

Jack R. Censer and Jane Turner Censer

George Mason University

Peter Schoeller’s 2018 film, One Nation, One King, provides two tales of the Revolution: the first is the formal revolution that shifts power from the king to an assembly of deputies representing the people (although none come from the bottom ranks); the second is the revolution from the perspective of the peuple, the working folk, men and women, and how they become politicized. While the first necessarily involves actual historical figures, the second is purely fictional, although surely informed by the work of historians who have chronicled the lives and politics of the peuple. The movie intersperses the political events that lead to Louis XVI’s downfall and his eventual execution with vignettes that show the revolutionary experience of artisans and peasants. The fast pace of the action and the scanty introduction of characters, even major ones, can make viewing difficult for a general audience. Yet, the film offers a strong vision of the Revolution, one that is very sympathetic to the radical deputies (mainly identified as Jacobins) and the Parisian working-class, situating them within the complex transformations that occurred during the highly consequential period of July 1789 to January 1793.

The conventional political part follows the interaction of King Louis XVI (Laurent Lafitte) with the various governments that replaced the Estates General: the Constituant and Legislative assemblies, the Convention. The film’s other story focuses on violent eruptions that framed the popular revolution – – events such as the taking of the Bastille, the July 1791 Champ de Mars massacre, and Parisian journées, illustrating them through a fictional family of a Parisian glassblower (Olivier Gourmet), his female relatives who are laundresses, and friends in various crafts.

To compress such a complex history into two hours, the director has chosen to illustrate a series of discrete events. The film opens with a depiction of the Old Regime as an organic society whose social structure, though highly stratified, could express the elite’s concern for the poor. In fact, the film’s opening sequence shows Louis XVI washing the feet of poor children at Easter, a sign of the religious bond between the sovereign and his people. In a foreshadowing of future events, one of the boys impudently asserts that he soon will have clogs, instead of bare, or barely clad, feet.

Stressing economic deprivation as the reason for revolution, the film depicts the hardships faced by the capital’s working people (more specifically the faubourg Saint-Antoine): poor housing, backbreaking work, ill-fitting, ragged clothing, and a lack of food as the lot of the populace. With little attention to how such conditions translated into political rather than social demands, the film asserts that they lead to the creation of a nation representing and embodying France’s working population – in short, a revolution whose impact is positive and quite admirable.

For classroom use, this interpretation of the Revolution’s origins requires serious consideration. Decades of scholarship on the causes of the revolution refocused attention away from the popular misery that Marxist historians such as George Rudé had stressed, to a myriad of other causes. In fact, the French Revolution was far more a revolution by elites to solve France’s financial problems. Without denying the real poverty in cities and countryside, scholars located the outbreak in 1789 within the “bourgeoisie” and even the nobility. This “notability,” an unspoken alliance between some nobles and educated commoners, demanded that the king share his authority. The focus shifted to the contest between the sovereign lawcourts and the king over a plethora of issues since the middle of the eighteenth century. What energized these protests was the increasing national debt and the need to raise royal taxes. This forced the king to build support within the “public,” particularly the nobility and the highly educated and well-heeled middle class. And indeed, a deal was struck that could help the monarchy’s finances and respond to the demands for power sharing. In 1789, the king called for a meeting of the Estates General, the nation’s traditional representative body, to answer the cry for wider participation. As this body had not met since 1614, its form and duties were uncertain, but it could stand in as a national parliament and provide a platform to solve the budgetary crisis. More important, elections were held in which the peuple were able to participate in the primary round through their parishes. Then the actual deputies emerged through secondary or tertiary elections so that the national legislature (the National Assembly) that emerged gave the populace no more than a symbolic role.

Yet the working people, especially in Paris, believed that these elections and the assembly’s decisions really opened the door wide to “liberty,” whatever that might come to mean. Although the people had gained some political role in the elections for the Estates General, they had to maneuver through the cracks left by elites. Divisions within that elite created major political opportunities for the working people that the film richly documents.

The film barely touches on the series of extraordinary events that led to the first gathering of the Estates General in 175 years, moving instead to the action of the crowd to seize and demolish the Bastille. One Nation, One King makes Parisian workers central to the iconic events of mid-summer 1789. In the battle over the Bastille we see only the people of the faubourg Saint-Antoine that had always felt threatened by the military fortress and prison. Despite the unrelated death of a baby, a raucous joy permeates Parisian working men and women, who significantly claim that the fortress’s demolition allows the light to reach them as it bathes their faces. A woman in the throng exults that this “liberty” will provide bread and rights. In short, the film shortchanges the political role of elites in favor of the direct action of the poor.

The film’s two tales unspool in parallel fashion in the series of uprisings or “days” that occur as the Parisian crowd pushes the political process in a radical direction. Particularly gripping is the film’s dramatization of the women’s march from Paris on October 5, when thousands walked to Versailles where the Assembly (composed of the former deputies to the Estates General less many of its noble members) now asserted its sovereignty. The women marchers demanded both bread and political liberty. Storming the assembly hall in Versailles, they braved the mockery of some noble delegates and slept wherever they could, even in the assembly hall itself. Through its participants’s songs, this version of the march asserts the community among working-class women and harkens to an era still dominated by oral communication.

In the film the king agrees to move his family to Paris after the head of the National Assembly asks him to do so. Moreover, and much more consequentially, he signs the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 26 August, a document that guaranteed rights far beyond what had been demanded in May 1789. It also portrays the development of events in the ongoing revolution. Calmly but sadly, Louis XVI closes up Versailles, whose shuttering of windows and extinction of chandeliers symbolically indicates the end of the old regime and monarchy.

Here the film strays in many ways from the historical record, but two changes are particularly important. First, the film downplays the threat of violence of the march and the invasion of the Assembly. Second, although Louis XVI seems gracefully to concede to the women’s demands, the royal family actually contemplated evacuating the palace to move to the more defensible Rambouillet, twenty miles farther from Paris.

As the Revolution unfolds, the film focuses increasingly on Paris where the people and the legislature now converge. The people wish further constraints on the king’s authority and find a hero in Robespierre (Louis Garrel) who argues for equality in the assembly. Although the film suggests that few know his name (showing its different spellings) and that he is ridiculed by noble deputies, actually Robespierre provided powerful encouragement to the egalitarianism expressed by those who witnessed the proceedings in the galleries. The radical press elevated Robespierre and made him the face of demands for popular sovereignty.

Portraying a revolutionary fervor that has spread to the countryside, the film introduces its romantic leading man, Basile (Gaspard Ulliel), imprisoned in the stocks for theft. Displaying anembrace of the Revolution, the village priest first frees Basile, then convinces his bourgeois victim to hire him. Such a reconciliation and peasant support of the Revolution are plausible in this period, but such social unity would not last.

As revolutionary hopes blossom from 1789 to 1791, the film illuminates important political developments, including valuable reforms: a constitution was passed; Jews could be citizens; church land was seized and sold to reimburse France’s debt. An effort to enfranchise women drew, not surprisingly, ridicule, even in the artisan family. But these circumstances also created a political rift between the working classes and their economic superiors.

Anxiety, in fact, flowed through all classes in revolutionary France. In arguably the oddest segment of the film, Louis XVI dreams of several of his powerful and successful predecessors, Louis XIV (1638-1715), Henri IV (1553-1620), and Louis XI (1423-1483) who berate him for his weakness. Defending himself, Louis XVI explains that he maintains control through his ability to veto legislation (In theory, he was correct, as its terms would have allowed him to delay legislation over a decade, but these powers were abrogated as the monarchy faced abolition.) This dream sequence concludes with royal calls for Louis XVI to wage war. Kings, the former monarchs insist, must seize the initiative in order to shape “history.” Yet the film demonstrates Louis XVI’s lack of resolve by showing his capture and that of his family in Varennes as they flee toward the eastern border on June 20, 1791.

Here the movie brings together its real and fictional characters as Basile, our former convict, like other curious peasants, stops his work to stare at the procession of the captured royal family moving through the countryside back to Paris. As part of the most ambiguous interaction, Basile bows before the king and receives the royal touch, an action believed in some circumstances to cure illness. The two are moving to Paris but in a different arc: Basile headed toward a new responsible life; Louis going back to face a resurgent assembly and eventually arrest, imprisonment, and death.

At the center of Basile’s new life is Françoise (Adèle Haenel) a pretty and feisty washerwoman, the glassblower’s niece who was shown as a fervent revolutionary in the opening scenes. They soon become lovers; in the midst of their romance she shows him a lace handkerchief that the Queen dropped, obviously prized by Françoise – providing a strange, even somewhat pro-monarchical, parallel to Basile’s encounter with the king.

Louis’s capture at Varennes averted a major crisis as he is brought to the dock of the National Assembly. Marat (Denis Lavant), the most radical of all the delegates, labels the king a traitor. Others join in while some representatives continue to argue for a necessary balance between king and people. Division continues, as Barnave, one of the leading “moderates,” endeavors to resist the radical tide.

With the king’s return to Paris in June 1791, confidence in him had begun – and continued — to unravel. Regrettably the movie barely mentions an important factor in the radicalization of the people of Paris: war clouds that signaled the hostility of European powers. The film shows the hardening of Parisian opinion, but makes it hinge exclusively on the treachery of Louis XVI rather than the fear of foreign war. The peuple mixes with the most radical club of the city (the Cordeliers) and thus they, including the glassblower’s family, participate in a major demonstration at the Champ de Mars (July 17, 1791). There they are trapped in the slaughter of civilians by Lafayette and the National Guard troops that view the popular petition signed there as a threat to the moderate Revolution. Françoise’s sister is one of the victims. The film depicts utter chaos, but only fifty or so of the several thousands of demonstrators were actually killed.

The film then follows the radical turn of the Paris artisans. Debates occur in the sections (Paris was divided into 48 electoral sections that started to meet round the clock) where radicals, apparently in the majority, reject calls for moderation. Action switches from the street to the neighborhood political bodies (the sections), and to the national assembly where a call to arrest Lafayette fails to pass. The galleries, filled with Parisian activists, explode in anger.

The Legislative Assembly that takes over in September 1791 and shares power with the king, immediately faces the wrath of the people of Paris. Basile, drifting leftward as most of the sectionnaires, joins the insurrection. As an outward sign, he dons the bloodied shirt of a victim of the Champ de Mars. The people of Paris move from victory to victory, leading to the coup on 10 August 1792 where the king is at last arrested. Basile experiences the trauma of the day as he confronts a riderless horse, an omen of the destruction of the monarch as well as the monarchy. As Basile stands too close to a line of riflemen, he is temporarily deafened by the sound of the volleys. Or, the film may be suggesting that he no longer is open to further discussion or doubts. Along with Basile’s temporary deafness, the glassblower is blinded in the violence of the August days.

The film at this point slows down, making following developments easier, as the question of the king’s fate takes center stage. Once again, the national assembly experiences the confrontation between the representatives and those in the streets. A new body, a republic, is established. Accompanying this change is an open advocacy of Terror to produce order and reduce opposition; Danton and Marat emerge to defend this new order.

As the revolutionaries decide on the destiny of the king, the film departs strikingly from the historical record. With the abolition of the monarchy, the new national assembly, the “Convention,” is enbroiled in foreign wars. A trial, beginning in December 1792, concludes (with breaks) on January 17, 1793. The Assembly finds Louis XVI guilty, and he is executed four days later. The movie depicts only the vote on the king’s fate – it shows no trial. Robespierre states in the film that he does not need a trial to convict: Louis is an usurper of power – this is enough to judge him. While one might dismiss this merely as Robespierre’s opinion, the film offers no scenes of the actual trial, showing instead a succession of delegates voting for or against guilt and punishment. Here One Nation, One King does an obvious disservice to history by eliminating Louis’s defense, ably carried out by the former head of censorship Guillaume-Chrétien de Malesherbes. It also makes the Convention, and more generally the revolution, appear more arbitrary, even bloodthirsty, in its condemnation of the king. As Louis is facing his end, the artisan family also undergoes changes: Solange, the glassblower’s wife, redoubles her commitment to her work and the revolution; Françoise gives birth to a daughter, part of whose given name is Egalité. The glassblower trains Basile to take over his trade and Basile has to learn to bear the “heat” of the oven on his hands, surely a metaphor for revolutionary fire. Here the two stories again converge. Louis remains dignified but is almost completely erased in the scene of his guillotining. He resists having his hands tied, but the executioner insists. The crowd greets Louis’s severed head with cheers, though some, in yet another hint of royal magic, try to scoop up the blood with their handkerchiefs.

The movie’s conclusion suggests yet again the sovereignty of the people, as Basile becomes a skilled glassblower. His successful test is a globe – akin to the globe and scepter—that, more importantly, indicates the dominance of the people in the world. Of course, it remains to be seen how the people can wield their power over that globe.

One Nation, One King is a beautifully shot, carefully executed film. Can it be useful in the classroom? The film, as an entity, presumes previous knowledge that almost all undergraduates lack. Its episodic nature assumes a familiarity with the events of the Revolution that most North American students do not possess. But can smaller segments be useful? Here the answer would seem to us to be a tentative yes. The assembly’s notions about the king’s crimes, as shown in justifications for voting for or against his deposition or death, would seem quite useful as long as students are instructed about the actual trial. And the story of the fictional Parisian artisanal family could possibly be used to suggest the politics of the common people and, in particular, the politicization of women. Examining the interactions between the lovers, Françoise and Basile, reveals the working out of personal and political power between men and women in a milieu where new freedoms arrive as sovereignty moves from traditional authorities to new egalitarian-minded ones. In the end, the parts of One Nation, One King may be more useful than its whole.

Pierre Schoeller, Director, One Nation, One King (Un peuple et son roi), 2018, 121 min, color, France, Belgium, Archipel 35, StudioCanal, France 3 Cinéma, Les Films du Fleuve.

********

III. One Nation, One King

Janine Lanza

Wayne State University

Pierre Schoeller’s One Nation, One King offers a representation of the early years of the French Revolution with the narrative centered on the actions of a small group of Parisian workers and artisans. While prominent politicians like Marat, Danton and Robespierre do have roles to play in this story, their actions are given less importance than the actions of the Parisian people. The narrative of the film covers events from spring 1789 to the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793, not quite four years, a choice that accents the fast-paced tempo of events that unfolded during the first phase of the Revolution. This film packs in many of the best-known events of those years, from the Storming of the Bastille to the Women’s March to Versailles to the development of the radical phase of the Revolution and the trial and execution of Louis XVI. In some ways this is a formulaic representation of the Revolution, with the focus resting on events in Paris and the political interplay between the representatives of different political factions in various iterations of the Assembly and the politically aware population of Paris. While characters refer to events taking place elsewhere, and one man from Varennes joins the Parisian band this film follows, it is largely mute on the experience of the Revolution outside of the capital city.

Schoeller’s telling of his story sees politics as central to the accomplishments of this era. This focus is reflected in the title of the film, One Nation, One King, which promises an exploration of the relationship between the monarch and his subjects during this era of political upheaval. However, the promise of the title is not carried through the film. Louis rarely interacts with his people. The film begins with a scene of Louis washing the feet of children during Holy Week, a scene meant to evoke the care a king took of his most vulnerable subjects. But Louis is oddly detached from the hardship these children suffer, evoked by one child wishing he might have shoes one day to put on the feet his monarch has just cleansed. Louis is featured in another scene which evokes his nightmare of having to face his illustrious predecessors who upbraid him for not being a strong monarch. The sense of nation and king we glean here is that the king should create that bond through a firm hand that would put down political uprisings. Louis XIV, Henri IV,and Louis XI, the kings who harass Louis XVI over losing control of his kingdom, used force to put down civil unrest. But Louis XVI, despite his despair over his inability to respond this way to his subjects, still fails to restore a bond with the people.

Almost all we see in the narrative are revolutionary exploits with the film moving from one marquee event to the next, punctuated by popular responses. One central thread that holds this choice of narrative together, with its multiple characters and multi-layered story lines, is the place of the National/Constitutent Assembly as the center of the events, politics and people of the Revolution. While Schoeller’s decision to follow a group of ordinary workers and artisans suggests that his tale will be that of the ordinary French man and woman living through the 1790s, he still relies heavily on the Assembly’s actions to move the story forward and to make his point about the centrality of politics. However, this organizing mechanism represents a very static view of these historical events. All revolutionary roads lead to Paris, and in particular to politics and political debates in Paris.

One particular example illustrates the way that Schoeller’s emphasis on political ideas and debate, rather than violent action, shapes his focus on the actions of ordinary Parisians. An important element is the prominent role the director gives to women in the unfolding of the Revolution. Female characters are present and involved in all of the moments he chooses as key to the course of the Revolution. Women were indeed active players during the Revolution, taking up arms, marching in protests, fighting and arguing for their political and personal rights. The seminal event occurred during the October Days, when thousands marched from Paris to Versailles with the goal of procuring bread for a hungry city and bringing the king, and the political process he was presiding over, to Paris. In the movie we see these Parisian women arguing with members of the newly constituted National Assembly, defending the goals that propelled their march. Eventually the women, using a rather sophisticated vocabulary of political rights, persuaded the representatives that their need for bread was real and their wish to bring the King to Paris should be supported. We then see these Representatives use the women’s arguments to persuade the king to come to the capital, and the royal family’s subsequent journey.

What is missing in this episode is the direct, violent action by some of these Parisian women that induced the royal family to abandon their home and move to the capital. While members of the Assembly did play a role in this episode, the women of Paris acted directly to convince the king to heed their requests. The president of the Assembly was accompanied by several women when he spoke to the King, convincing the reluctant monarch that his best course was to give in to their demands. More famously, a number of women found a way into the palace of Versailles and fought their way to the royal chambers. Edmund Burke in his 1792 work Reflections on the Revolution in France described these Parisian women in lurid prose, referring to them as “the unutterable abominations of the furies of hell, in the abused shape of the vilest of women.”[1] While this characterization of the women who marched to Versailles is tendentious and hardly corresponds with Schoeller’s interpretation of the role of the people in the Revolution, the women did nonetheless engage in direct violence. Many royal guards were killed during the October Days and it was in part this violent response that pushed the reluctant royal family to abide by the agreement to leave Versailles.

The March to Versailles of 5 October 1789 is not the only instance where the violence of the event is largely sidelined. Schoeller’s decision to downplay the violence that formed a part of the Revolution, and of the direct action of Parisians, distorts how his viewers perceive the dynamic of the Revolution with respect to direct action. Schoeller does show bloodshed as part of the Revolution, but for the most part that cruelty is inflicted on the people by a repressive government. Near the beginning of this film, we see the Bastille fall under the righteous rage of Parisian men and women. Some violence is hinted at but the major victim of violence here is the fortress itself. Men and women work together to take apart the bricks of the prison whose hulking presence has blocked the neighboring streets from the sun. Schoeller’s narrative does show that the crowds of Parisians who attacked the Bastille did kill some soldiers, and that scene sets the tone for his treatment of popular violence throughout the film. A group of people surround the artisan who beheaded Bernard Rene Jourdan, the governor of the Bastille. The man is weeping in the midst of a congratulatory crowd, insisting that he did not intend to kill the governor, that someone jostled him as he held his knife, and it somehow pierced Jourdan’s neck and, voilà, the governor’s head was separated from his neck. While the man’s claim is treated as implausible by his comrades, he insists he did not mean to harm the governor.

This disavowal of violence by the people, who only kill accidentally or in self-defense, contrasts with government troops who use physical force to put down Parisians when they are simply seeking to assert their rights. The massacre of the Champ de Mars on 17 July 1791 is treated as a particularly dreadful example of the royal government’s violent response to nonviolent protests. Peaceful Parisians had assembled to sign a petition demanding a Republic (after the King’s flight to Varennes in June to join enemy armies) and were happily picnicking when, suddenly, horses and soldiers began mowing them down. All the crowd was doing was to call for justice, in the form of a trial of the King, and a transition to a republican form of government. The response of the government to these reasonable demands was a charge by soldiers intent on killing the Parisians. This use of political language by Parisian workers and artisans is an important part of the film. From the start of the Revolution, as at the attack on the Bastille, the characters in this film speak of liberty and political rights – for both men and women. They engage in multiple nuanced conversations about these ideas. When these Parisians take to the streets it is in the service of these ideas, and with the intention to press for rights. The recourse to violence is a last resort, responding to the dismissal of their ideas. While this language of political rights presents the viewer with some context for the ideas being debated in this era, it distorts the stance of many who participated in the Revolution and their understanding of the different shades of meaning of this political vocabulary.

For those who use this film in the classroom, that decision to use a nuanced political tone to portray how Parisians understood the Revolutionary era and their role in it could present both opportunities and challenges. While this film has some elements to recommend it for classroom use – the prominent role of women and the focus on workers and artisans – its distortions will require explanation of other aspects of the Revolution that are not explored here: for example, the direct violence by Parisians to steer the course of the Revolution and to support their political goals. In comparison to other films that portray the Revolutionary era, this film also has a claustrophobic feel. Most of the action takes place in rooms, dark rooms; the prominent role of the streets as the setting for many important events of the Revolution is not clearly conveyed. Also, the focus is almost solely on Paris, overlooking the ways that French men and women elsewhere understood and participated in the Revolution.

This film does offer a perspective on popular participation in the Revolution, and the inclusion of a debate over political issues does provide a corrective to films, like numerous adaptations of A Tale of Two Cities for example, that linger over the brutality of the crowds. However, its melodramatic acting, its peculiar love story, and the propensity of the characters to loudly declaim much of their dialogue (which does seem to be an element of several French films dealing with this historical period) are all issues to be considered when choosing a film for undergraduate students.

Pierre Schoeller, Director, One Nation, One King (Un peuple et son roi, 2018, 121 min, color, France, Belgium, Archipel 35, StudioCanal, France 3 Cinéma, Les Films du Fleuve.

NOTES

- Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, (New York, 1989), p. 85.