Laura Mason

Johns Hopkins University

It is not easy to write about Les enfants du paradis, although that is not because of the movie’s form. A tale of four men in love with the same enigmatic woman, which unfolds among the popular theaters of the early nineteenth-century Boulevard du Crime, the movie is aesthetically dazzling. Reuniting screenwriter Jacques Prévert and director Marcel Carné, authors of poetic-realist classics like Le quai des brumes and Le jour se lève, Enfants is graced with indelible performances. Jean-Louis Barrault, as the idealistic man-child Baptiste, Pierre Brasseur as the buoyant Frédérick, and Arletty as the worldly Garance make us believe fully in the ideal types they inhabit. Set designer Alexander Trauner’s elaborate façades conjure a Paris boulevard that extends as far as the eye can see, while cinematographer Roger Hubert’s deep, overflowing shots immerse us in the crowds teeming there and the chaotic backstage activity that animates their entertainments.

What makes Les enfants du paradis so difficult to write about is uncertainty about what historical period it should be taken to illuminate. Is this principally a movie about Vichy France, where it originated? Or should we focus on the popular milieu and boulevard theaters of nineteenth-century Paris that it so enthusiastically celebrates?

Commentators inevitably take the first line of attack. They do so with good reason, for Les enfants du paradis is intimately linked to the French Occupation. Although that story has been repeated ad infinitum, it bears summarizing to make clear the constraints under which director Marcel Carné and his fellows worked. Conceived and written in wartime, the movie began production in August 1943 with the construction of an elaborate set in Nice and was almost immediately interrupted by the Allied invasion of Italy and Nazi harassment of producer André Paulvé. Carné found another producer and did some shooting in Paris but was unable to return to Nice for months. By that time, the set had been so badly damaged by winter weather that he had to raise more funds and hustle up further materials amidst wartime shortage to rebuild.

Even then, difficulties persisted. Film stock was difficult to come by, transport uncertain, regular cuts in the power supply guaranteed. Every kind of relationship to the German occupiers was visible among cast and crew. Designer Alexander Trauner and composer Joseph Kosma were employed using fronts because both were Jewish. Spanish republican exile Maria Casarès, who plays Baptiste’s hopelessly besotted wife, was linked to the Resistance, as was at least one extra arrested by the Gestapo. On the other side was actor Robert Le Vigan– initially cast as the rag-seller whose commentary punctuates the film– who fled France in 1944 as a collaborator, and the actress Arletty, who was publicly involved with a German officer.[1]

Nonetheless, Carné completed the film. He even slowed its production to insure that his would be not the last film of the Occupation but the first of Liberation. He managed that too. Les enfants du paradis premiered in Paris in the spring of 1945. Although the producers, and Carné himself, had doubted that a three-hour film would play well, it was a wild success. The first run continued for more than a year, earning 41 million francs as critics sang the movie’s praise. Georges Sadoul called it a chef d’oeuvre, wondering if Carné and Prévert would ever “surpass such perfection,” and the Venice Film Festival gave it a prize in 1947. The movie was considered a triumph over dark times and, even today, is described as “a form of ‘symbolic resistance’” to the German Occupation. That it also represented a collective thumbing of noses at America, proof that the French film industry could beat Hollywood at its own game, was further cause for celebration.[2]

The impact of Vichy on the production of Les enfants du paradis was significant and our knowledge of those conditions undeniably enhances our appreciation of its achievement. But what is missing is more reflection on the world the film represents: that of early nineteenth century Paris.

The plot of Les enfants is anchored in the early nineteenth-century boulevard du Temple, known as the “Boulevard of Crime” because of the melodramas performed by the popular theaters there. Like any good historical fiction, it mingles real figures from that milieu with invented characters. The central protagonist, Baptiste, is based on the great nineteenth-century mime Jean-Gaspard Debureau, whose arrival on the stage of the théâtre des Funambules and mounting fame the movie charts. As Dubureau did in real life, Baptiste initially shares that stage with the actor Frédérick Lemaître, whose growing renown and maturation to play Othello functions as a subplot. Both men cross paths with a third figure whom both were likely to have known of: the notorious dandy-murderer who fancied himself an author, Pierre François Lecenaire.[3] The action is also driven by the fictional Garance, a part-time actress, casual sex worker, and free spirit to whom all three men are devoted, and who catches the eye of a similarly invented character, Edouard, comte de Montray.

Although readily linked to a specific place and particular historical figures, the precise years that Les enfants spans are, as Jill Forbes has pointed out, difficult to fix. Director Marcel Carné claimed that it “takes place ‘round 1840” but a published version of the script has it beginning in 1827 or 1828, while noting that “the precise date does not matter.” Some copies of the film put “1830″ at the beginning of the first part.[4] Details of the plot further confuse the issue. In the first part, there are several references to an injunction against speaking on stage at the Funambules, which historians know to have been abandoned after the July Revolution.[5] In the second half, a few years on in the chronology of the narrative, we see Baptiste perform Debureau’s “pantomime-macabre,” The Old Clothes Merchant, which dates from 1840s while, down the street, Lemaître is reconfiguring L’Auberge des Adrets, which we know him to have done in the early ‘20s.[6] And whether occurring in the 1820s, ‘30s, or ‘40s, there is egregious anachronism when Garance and Baptiste look out over Ménilmontant during a late-night walk to see the twinkling lights of a late-century suburb rather than the tiny village of the century’s first half.[7]

But to focus too closely on precise years is to lose the forest for the trees. Although some, like Forbes, have asked “when exactly?” no one has explained why this particular past appealed so forcefully not just to Prévert and Carné but, most significantly, to their devoted contemporary audiences. Certainly, directors in Occupied France preferred stories set in the past because they more readily evaded censorship, but no historical film of the era flourished quite like this one. Even the Carné-Prévert fable that preceded– Les Visiteurs du Soir (1942), which was set in the Middle Ages– did not do so well then nor endure in the same way.[8] If Les enfants du paradis is indeed France’s Gone with the Wind, as many have claimed, what sort of national history did it imagine for a newly liberated nation?[9]

The title tells us immediately who the film celebrates, for those who sat in the cheap seats of the paradis [“the gods”] were ordinary folk. And at least two of the central protagonists come from that fraction of society: as the mime Deburau, Baptiste is “a working-class hero of the arts” and Garance tells us that she is the daughter of a laundress, whose death left her alone in the world at fifteen. “Around here,” she adds wistfully, “a girl who grew up too fast doesn’t stay alone for long.”[10] We know nothing of Frédérick’s origins but his generosity and sense of humor put him firmly on the side of the people. The bourgeois dandy Lacenaire and the aristocratic comte de Montray, on the other hand, are not in the least sympathetic.

However, the opposition between lower and upper classes is more than just a “historically charged rejection of [the] ambiguity” of Vichy, as Alan Williams has argued.[11] It is integral to the film’s embrace of Jules Michelet’s insistence on the “sacred poetry” of “humble” lives and location there of the nation’s essence.[12] Carné and Prévert evoke humble lives in ways that recall not just Michelet’s rhapsodizing but that of his Romantic contemporaries and their descendants. When Baptiste accompanies a blind beggar to a popular dance hall, he is astonished to see the man abruptly “recover” his sight like the inhabitants of the cour des miracles in Hugo’s Notre Dame de Paris. When a thug tosses Baptiste through a window, the latter returns through the door, nonchalantly dusting himself off like a character from a Guignol puppet show.

This celebration of le peuple is linked to the setting, for where better to find charming lower classes than in the theaters of Michelet’s era? Carné grounds us there from the start, raising a curtain to open the movie, plunging us into the crowds on the Boulevard du Crime, and sweeping us along to find Baptiste masquerading as the iconic Pierrot. Writer and director sustain the link between stage and popular life by revisiting the film’s key plot points through staged pantomimes in which Baptiste, Garance, and Lemaitre re-enact allegories of what they have just lived. And they subtly widen the definition of le peuple by re-staging Frédérick Lemaître’s astonishingly self-reflexive performance of Robet Macaire, which brought bourgeois audiences into the palaces of popular entertainment as it helped modernize the melodrama.[13]

Above all, Carné and Prévert immerse us in the world of the nineteenth-century popular theater by infusing their tale with that same melodrama. For Les enfants is melodrama through and through. If the actors give humanity to ideal types, we still recognize the type. Baptiste is the starry-eyed romantic and Garance, the worldly woman whose laughter masks suffering. Frédérick rises in the world but remains ever the clown. Lacenaire is the depraved genius, right down to his neat black mustache. The comte de Montray, an aristocrat, is incapable of enjoying life’s simple pleasures. The acting is melodramatic as well, founded on bold declarations of passion that stand in contrast to the naturalism of 1930s social realist films and even more modest Vichy movies like Jean Grémillion’s Le ciel est à vous. Finally, the movie ends as a melodrama should, allowing the audience to shed tears for the good and take solace in the punishment of evil. It is a wistful ending but one that restores order to the world, an appealing message for those whose own world had been so profoundly disordered. France, Les enfants du paradis intimates, will always be France, le peuple will endure, the nation will recover its essence.

That Prévert and Carné deliver this message through melodrama is integral to the film’s appeal. As a “dramaturgy of excess” that portrays “choices… of heightened importance,” melodrama was well suited to a nation emerging from the complex moral environment of Vichy and the German Occupation.The movie acknowledges that virtue does not always triumph in the ways we hope, but it highlights the good and promises that evil will be defeated.

Les enfants du paradis remains a visually beautiful and emotionally satisfying movie. But it may have spoken to the newly liberated France in an especially evocative way precisely because, by celebrating the Boulevard du Crime, it laid claim to a national past rooted in the culture and aspirations of ordinary folk. Like Michelet, Prévert and Carné insist that the soul of the nation is to be found in le peuple who, by living, loving, and enduring, will guarantee its survival.

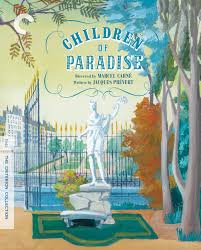

Marcel Carné, Director, Les enfants du paradis [Children of Paradise],1945, France, b/w, 189 min, Société Nouvelle Pathé Cinéma

NOTES

- Jill Forbes details this production history in Les Enfants du Paradis (London: BFI Publishing, 1997). It is summarized by Jean-Pierre Jeancolas, “Beneath the Despair, the Show Goes On,” Susan Hayward & Ginette Vincendeau (eds.), French Film: Texts & Contexts, 2nd edition (London & NY: Routledge, 2000) and Ben McCann, “Les Enfants du Paradis,” Phil Powrie (ed), The Cinema of France (London: Wallflower Press, 2006). Detail about the Gestapo’s arrest of an extra is in Brian Stonehill’s interview with Marcel Carné, in the booklet that accompanies the Criterion Collection DVD (2012) 34. On Marie Casarès, see Maria M. Delgado, ‘Other’ Spanish Theatres: Erasure and Inscription on the Twentieth-Century Spanish Stage (Manchester & NY: Manchester UP, 2003) 90-93.

- On the premiere, see Jill Forbes, Enfants. 9. Reviews are reproduced at the website https://www.marcel-carne.com/les-films-de-marcel-carne/1945-les-enfants-du-paradis/fiche-technique-synopsis-revue-de-presse/#revue (accessed 5 May 2020). On the movie as “symbolic resistance,” see Ben McCann, “Beneath the Despair.”

- Lacenaire alone was the subject of a lesser film, made several decades later and reviewed on this site by Thomas Cragin. See his “À bas la guillotine! Vive la bourgeoisie? Lacenaire and The Widow of Saint Pierre.”

- Jill Forbes, Enfants 18.

- Edward Nye, “The Romantic Myth of Jean-Gaspard Deburau,” Nineteenth-Century French Studies vol. 44 #1-2 (Fall-Winter 2015-2016) 46-64.

- Adriane Despot, “Jean-Gaspard Deburau and the Pantomime at the Théâtre des Funambules,” Educational Theatre Journal vol. 27 #3(Oct 1975) 364-376.

- Jill Forbes, Enfants 26-27.

- One critic (Sadoul) complained that its decor was “blanc et froid,” and another (Michel Braspart) that it was “un peu scolaire, didactique.” See https://www.marcel-carne.com/les-films-de-marcel-carne/1945-les-enfants-du-paradis/fiche-technique-synopsis-revue-de-presse/#revue.

- Ben McCann, “Beneath the Despair,” 58.

- Edward Nye, “Myth of Jean-Gaspard Deburau,” 50; Jacques Prévert, Marcel Carné Les Enfants du Paradis (Criterion Collection, 2012) 1:00:07-1:00:14.

- Alan Williams, Republic of Images (Cambridge MA & London: Harvard UP, 1992) 268.

- Jules Michelet, Le Peuple (Paris: Calman Lévy, 1877) xi, 112-113.

- On Lemaître’s reformulation of Robert Macaire, see Odile Krakovitch, “ Robert Macaire ou la grande peur des censeurs,” Europe (1 Nov1987) 49-60.