Gayle K. Brunelle, California State University-Fullerton

Annette Finley-Croswhite, Old Dominion University

Introduction

From the March morning in Paris in 1951 when Pauline Dubuisson, a 24-year-old medical student, shot her one-time lover Félix Bailly in his apartment on the rue Croix-Nivert, the Dubuisson case has fascinated the French public. The murder elicited a frenzy of press copy, public ire and soul-searching. Dubuisson’s scandalous wartime past, reputation as both a “loose woman” and an “exaltée” who sought to build for herself a career more fitting to a man shocked much of the French reading public, but so too did the harsh sentence, life imprisonment at hard labor, meted out to her at the end of the trial. One thing that becomes clear upon reading the various accounts of Dubuisson’s life is that evaluations of victim, perpetrator, crime, trial and punishment are all subject to the vantage point of the observer, in time, place, culture and, quite literally, “embodiment” and gender identity.

Dubuisson’s trial occurred in the early 1950s. France was still struggling to come to terms with the legacy of World War II, the Vichy regime, and the Occupation, even as the nation was also on the cusp of the generational turnover that led by the end of the decade to the momentous cultural changes of the 1960s. This evolution can be tracked in the shifting public and judicial evaluations of Dubuisson’s crime and sentence. During the trial, journalists and public opinion condemned her almost unanimously in the darkest terms. Within days of the verdict, observers began to express second thoughts. A period of soul-searching ensued that led many to argue that Dubuisson’s punishment was too harsh for what was essentially a crime committed in the heat of the moment, a crime passionnel that may have been a suicide gone wrong. During the years between her incarceration in 1951 and her release on March 21, 1960, her sentence was reduced several times, not only due to her exemplary behavior in prison but also because of growing qualms about its severity.[1]

The importance of perspective in evaluating Dubuisson’s life and her crime emerges in the two works under review here: Philip Jaenada’s reassessment of Dubuisson in La petite femelle and Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1960 film starring Brigitte Bardot, La Vérité. These two works are linked not only by their subject, the Dubuisson case, but also because Jaenada condemns the film for creating a distorted Dubuisson, an oversexed virago rather than the fragile and emotionally damaged woman he believes she was. Jaenada blames Clouzot and his film for reviving the notoriety surrounding Dubuisson just at the moment when she was attempting to rebuild her life. The film’s success, he argues, caused her tragic suicide in Morocco in 1963.[2]

The central issues here for historians are ones of genre and interpretation. For La petite femelle, reviewers must grapple not only with Jaenada’s assessment of Dubuisson, but also with the nature of the book itself. It is billed as a “novel,” but Jaenada denies that this is true despite the clear evidence of, if not fictionalization, certainly speculation about the motives and mindsets of both Dubuisson and those around her. This book is a hybrid, part of a growing corpus of works that, for lack of a better term, are generally labelled “creative nonfiction.” This type of work blurs the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction, reminding us that historical writing is, or at least originally was considered to be, a form of literature – not fiction, but not scientific analysis either. Yet at the same time those of us trained as historians are aware that there does exist a line, even if it is often fuzzy, beyond which a work of history evolves (or devolves, depending on your point of view) into fiction.

Our recent books Murder in the Métro (2010) and Assassination in Vichy (2020) have at times been considered to be fiction (which they are not) due to the quality of the writing and the narrative, which in each centers on a micro-history of a murder, much like La petite femelle.[3] But despite Jaenada’s extensive research, the similarity between his work and ours ends there. We do not permit ourselves the depths of psychological speculation (construction of character and point-of-view in literary terms) that Jaenada does. Moreover, from the outset Jaenada is clear that his aim is to advocate for Dubuisson and to rehabilitate the collective memory of her. His many digressions, which make sections of the book read like a memoir, draw comparisons between Jaenada’s personal experiences and those of other people he has known or interviewed, and those of Dubuisson and her adversaries. Jaenada thus seeks to bridge the psychological and cultural gulf between Dubuisson and himself and his readers, but this is a literary technique that historians hesitate to employ precisely because it renders historical analysis less reliable. Historians today recognize that “neutrality” and “objectivity” are chimeras.[4] But they also acknowledge that historians still must endeavor to guard a certain emotional distance from their subjects in order to assess the past as fairly as possible. That Jaenada does not even attempt to be a neutral observer is not a criticism of his book. Rather, it simply raises again the question of what this work is – a brilliant work of creative nonfiction – and what it is not – either a novel or an historical study.

Clouzot’s movie also elicits questions about what it is – a work of art, and probably Brigitte Bardot’s best film – and what it decidedly is not – a biography, accurate or otherwise, of Pauline Dubuisson. It is not simply that the film strays very far from the realities of Dubuisson’s life and crime, even though some of the details of the murder and trial are the same. The central issue is that La Vérité is neither set in, nor about, the era when the crime took place, the early 1950s, with all the wartime baggage with which France was still encumbered. It is not a film about the past. Rather, it is an assessment, and condemnation of Clouzot’s France in 1960, and of the future France already emerging, one younger, freer and, for Clouzot, utterly amoral and irresponsible. The truth of La Vérité is not the truth of Pauline Dubuisson at all, which is one reason why it is both ironic and tragic that the film still managed to cause such psychological damage to Dubuisson.

What We Know

To understand both the book and the film, we have to begin with what we know about Pauline Dubuisson. She was born March 11, 1927, the youngest child and only daughter of André and Hélène (Hutter) Dubuisson. Her parents were Protestants with ministers on both sides of the family. André was an engineer-entrepreneur, a World War I veteran, a colonel in the reserves, and an officer in the Légion d’honneur who owned a construction firm that engaged mostly in public works projects. André and Hélène prior to the outbreak of World War II were pillars of the bourgeoisie in the wealthy beach town of Malo-les-Bains (today part of the city of Dunkirk).

André was forty-five years old when Pauline was born. Pauline was more than ten years younger than her three brothers. Despite her gender she became the focus of her father’s aspirations. Two of her three brothers, François and Vincent, died young and the eldest, Gilbert, was fifteen years older than Pauline. In André’s judgement none of his three sons possessed the intellect or character that he discerned in Pauline. The death of Vincent, the brother closest in age to Pauline, in an aviation accident in 1936, deeply affected both her and her mother. Hélène, already timid and prone to depression, sank into a mental lethargy after Vincent’s death from which she never recovered. André thus became the dominant figure in Pauline’s life. Rigid and something of a martinet, he was emotionally distant while at the same time exerting close control over her upbringing. He ensured that his gifted daughter received a solid education, in advance of what many girls obtained in the pre-war years, and sufficient for her to continue her studies at a university. André also taught his daughter to exercise a firm control over her emotions and to despise failure. Life, for André, was an unrelenting competitive struggle in which only the strong could, and should, survive. Pauline developed a desire to study medicine and a great need to, at once, please her father and seek out the attention of older men. These traits led her straight into the arms of the Germans when they occupied Malo-les-Bains in June 1940, when Pauline was thirteen.

German officers and soldiers were everywhere in Malo-les-Bains, including literally right next door to the Dubuisson home. André needed work for his company to survive, and only the Germans were able to offer it. It was not long before he was frequenting the Germans, negotiating contracts and socializing with them, and since he had ensured that Pauline learned fluent German, he brought her along to translate. Soon Pauline was spending most of her time with the Germans, and it is unsurprising that the pretty and precocious fourteen-year-old attracted the attention of the soldiers. In 1941, she entered into a relationship with a young adjutant (at twenty-three already nine years older than she) and after his transfer in 1942 she had relationships with other Germans, liaisons she was rumored to have chronicled in a diary during these years. By 1944, as the Allies closed in on the city and the bombardments caused heavy casualties among the occupiers and the civilian population alike, Pauline began to work in the German field hospital under the command of Colonel Werner Domnick, the chief physician. She also became his lover, although he was at least forty years her senior. When the Germans finally retreated, collaborators such as André and his family were shunned and Pauline may have suffered the indignity of public head-shaving as well for her “horizontal collaboration” (the evidence here is unclear), although it is highly unlikely that she was raped, as some sources contend. To escape the disgrace, Pauline finished her schooling in Lyon.

In October 1946 Pauline began medical studies at the Faculté de médecine in Lille. There she met Félix Bailly, scion of a wealthy bourgeois family from Saint-Omer and also a medical student. She was twenty and he was five years older, and in February of 1947 they became lovers. Félix seems to have been infatuated with Pauline and asked her to marry him more than once. Pauline was reluctant, however, both because she wanted to pursue her goal of becoming a pediatrician, which would have been impossible once she became a wife and mother, and because she seems to have been unsure of her feelings for him. After two years, they broke off their relationship. Félix headed for the Faculté de médicine at the Université de Paris, while Pauline remained in Lille for another eighteen months and entered into a relationship with another young man. Meanwhile, Pauline decided that she was indeed in love with Félix and ready to commit to him. By that point, however, he had found another fiancée, Monique Lombard, and Pauline, desperate to regain his love, went to Paris in March 1951, to confront him and persuade him to return to her.

She had two encounters with Félix that March. When it became apparent to Pauline after spending the night with him on March 6-7 that he would not abandon Monique, Pauline decided to confront Félix again and this time she would kill herself in front of him if he did not relent. By this point she had become obsessed with regaining his affection. She returned to Lille and purchased a small revolver, and on Saturday, March 17, she went back to Félix’s apartment on the rue de la Croix-Nivert and shot him three times after, she claimed, he attempted to stop her from shooting herself. She maintained that Félix’s death was an accident, and the police found her in Félix’s kitchen, near death after trying to kill herself by gas from the stove. Pauline’s father committed suicide within forty-eight hours after hearing of his daughter’s arrest, and Pauline was forced to face trial with little support from her family or friends. She was tried in Paris in 1953 and in October, during the trial, attempted suicide again. Pauline survived and was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison, although she was released in 1960 for good behavior and because of the public outcry over her harsh sentence that began almost immediately after the conclusion of the trial. Pauline continued her medical studies and migrated to Morocco where she practiced medicine technically as a nurse but in reality as a medical intern and began using one of her middle names, Andrée, to identify herself.

Andrée/Pauline seemed to be doing well in Morocco, and the physicians with whom she worked held her in high esteem, as did her patients. She entered into a new relationship with a French engineer close to her own age, Bernard Krief, who asked her to marry him. But in 1960 La Vérité was released. The film starred Brigitte Bardot as Dominique Marceau. Although Dominique’s character was quite different from Pauline, the film was based on the events surrounding Pauline’s relationship with Félix, his death and the ensuing trial. The resemblance was close enough that journalists drew the connection and an article written in Paris-Match revived the Dubuisson affair. Tragically for Pauline, the article made its way to Morocco and by the spring of 1963 she had to inform Krief about her past. Krief broke off their relationship and after spending months mired in depression, Pauline committed suicide on September 22, 1963.

La petite femelle

In La petite femelle Philippe Jaenada has written a truly hybrid book, a masterpiece albeit one that does not fit neatly into any genre. Jaenada, a novelist and a journalist, brought his skills in both literary forms to this project. Although the book has no footnotes, Jaenada thoroughly researched his subject, reading trial transcripts and police reports, scouring the press for articles on Dubuisson, and interviewing witnesses whenever possible. His immersive research resembles that of an historian and exceeds all but the best investigative journalists. He wants his readers to feel what Pauline is feeling, to see inside her mind, and for that he is willing to call upon his skills as a novelist to create Pauline as a character, one that he believes is based on the evidence and reflects a truer picture of her than what had been written about her before.

To understand this work, we must grasp Jaenada’s goal, which was neither to create a historical fiction nor to author a biography. Rather, Jaenada places himself in the role of an advocate for Pauline Dubuisson, to do the work that the journalists of her day and her lawyer, Paul Baudet, failed to do. No one, Jaenada argues, saw the real Pauline. The woman tried in the press and in court in 1953 was a caricature created through a combination of misogyny, laziness and the legacy of wartime hatreds that rendered journalists, the police and Pauline’s judges – even her own lawyer – unwilling or incapable of understanding her. What made the case particularly difficult, and susceptible to prejudices about Pauline, was that while there was no doubt about who pulled the trigger on March 17, there was no hard evidence about why. Was the murder a crime passionnel, in which Pauline brought the gun to Félix’s apartment because she intended to kill herself, not him, and only shot him in the heat of the moment when he tried to wrest the gun away from her? Or was it, as the prosecution contended, a cold-blooded act of premeditated murder resulting from Pauline’s anger and humiliation because Félix no longer wanted her? In the absence of solid evidence either way, Jaenada demonstrates convincingly that the court condemned Pauline and handed down an exceedingly harsh sentence because they were judging not the crime but Pauline herself, for who she was, not for what she had done. In La petite femelle Jaenada sets out to reinterpret Pauline and show how she was the victim of her own troubled upbringing, and outmoded bourgeois attitudes regarding gender and female sexuality, and France’s still visceral angst regarding wartime collaboration.

The tragedy of Pauline Dubuisson’s life, Jaenada contends, resulted from the fact that her natural talents, upbringing and wartime experiences made it difficult if not impossible for her to fit into the cultural expectations of her society for a young woman from a well-to-do bourgeois family. Men consistently took advantage of Pauline, trying to control her for their own ends. Her father raised her, if not as a son, certainly not in a manner that would have prepared her for the roles of wife and mother that her society expected her to play, and her mother’s misery and subservience to André offered little for Pauline to emulate. Moreover, her father, who seems to have treated Pauline as the companion his wife could never be for him, actively encouraged her daily socializing with the Germans in Malo-les-Bains, and at the least did nothing to discourage her relationships with them from becoming sexual. André and his eldest son were collaborators themselves, and Pauline’s relationships with the Occupiers certainly did not hurt the family’s economic prospects. But even after the Germans had no more contracts to offer Dubuisson, André turned a blind eye to his teenage daughter’s sexual activities.

After the war the Dubuisson family reputation was stained but, predictably, it was again Pauline who bore the weight of the public shame directed at her family. She managed to recover and continue her education. It was her determination to fulfil her dream of becoming a doctor that, in Jaenada’s view, induced her to reject Félix Bailly’s repeated offers of marriage. Although he was older, Pauline was more sexually experienced and worldly than he. Jaenada sees her as only a little ahead of her time, her life anticipating the sexual revolution and women’s liberation movement of the sixties, whereas Félix’s feet were still solidly planted in outmoded pre-war attitudes toward gender and class. It seems inevitable that they would have clashed, and one of the mysteries that Jaenada does not really elucidate, is why Pauline decided that Félix and the life he was offering her were what she wanted after all, and became so obsessed with having him that she was willing to kill herself, or him, if she could not. The prosecution and the press blamed this change of heart on wounded pride and spite, but it is likely that Pauline was more fragile, troubled, and emotionally wounded than her adversaries, or even Jaenada, recognized.

Interpretations of reality, in one’s own times or the past, always derive from the situation of the observer. Those who condemned Pauline in her own day did so from the starting point of who they were, which then determined who they thought she was. This is also true of all those who have written about her since then, including Jaenada, who inserts himself into every chapter through digressions. His understanding of Pauline is based as much on his own experiences and perceptions of life, love, and sex, as they are on those of Pauline, leading him to intuit much more about her motivations than most historians would ever attempt. While this approach often yields great insights it also results in certain gaps in Jaenada’s grasp of Pauline.

One of the most important of these is an underestimation of how damaging Pauline’s precocious sexual experiences with the Germans were to her psychological development. Pauline was still a child, not a woman, when she became the mistress of a German officer in 1941, and she was only seventeen when she entered into an affair with Colonel Domnick, who was decades older than she. Today her emotional instability as an adult – depression, suicide ideation, and unstable relationships – would be viewed as the direct result of the emotional abuse she suffered at the hands of her father, her poor relationship with her mother and, especially, the sexual abuse she endured from the German soldiers. Whether or not Colonel Domnick “pleased” her as she claimed in court in 1953 and even though she was not technically raped, the reality is that all her affairs with German men were based on unequal power relations while she was “underage.” Malo-les-Bains was occupied, her father’s prosperity depended on German good will, the city was bombarded and food and supplies for civilians became increasingly scarce, especially in the later stages of the war. German men, in particular officers, had power that she, or even her father, lacked. It was impossible for a vulnerable adolescent girl under these circumstances not to have been traumatized, despite Pauline’s brave face toward the world and unflinching determination to pursue her medical degree. Pauline Dubuisson may have been, as Jaenada sees her, a woman struggling to liberate herself from the stultifying sexual mores and restrictive gender roles of her society, but she was also seeking, and failing to find, an escape from the emotional trauma and sexual abuse she endured during the war. Her story is one of abusive sexual relationships and men who use and discard women. This is one of the few ways in which Clouzot’s La Vérité, ostensibly based on Pauline Dubuisson’s crime and trial, actually mirrored Pauline’s life.

La Fausseté of La Verité

On the surface it appears that La Vérité is a factual recreation of the courtroom drama surrounding the sensational trial of Pauline Dubuisson, told in a series of flashbacks leading to the climax where she shoots and kills her lover. Clouzot used a team of five writers to produce the script including his wife, Vera Clouzot. They researched Dubuisson’s story and borrowed from it to shape the narrative arc and even the finer details of the storyline. For example, it was pouring rain the day that Pauline shot her ex-lover, and heavy rain figures in the film on the day Gilbert Teillier (played by Sami Frey) dies, a motif that only adds to the general gloom of the film. In fact, it is Gilbert’s decision to loan his raincoat to a friend that allows his ex-lover to sneak into his apartment moments before she shoots him. The association between Pauline and Bardot’s character, Dominique Marceau, strongly suggested that the film was a truthful retelling, an impression further solidified after Pauline’s 1963 suicide when it was rumored that the film’s popularity drove her to take her own life. The fact that during the making of the film Bardot attempted suicide herself in what is often described as a classic example of art imitating life, since both her character and Pauline slit their wrists, also intensified comparisons between the real-life events and the fictional film. Jaenada contends Clouzot used poor judgement in releasing La Vérité only seven years after the trial and in full knowledge of Pauline’s recent liberation from prison. Jaenada argues that Clouzot had to have known that the film which portrayed the main character as a sex-crazed assassin and exposed the world to “Bardolatry” (worship of Bardot and her sexualized image) would complicate Pauline’s effort to rebuild her life and might well even push her over the edge.[5]

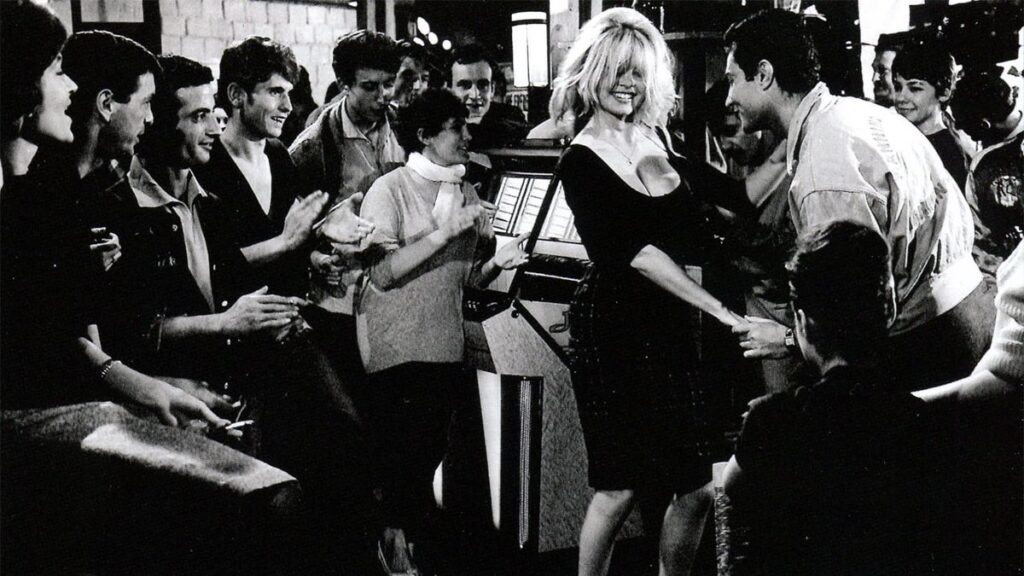

Upon closer examination, however, the comparison between Pauline and Dominique ends and therein drives the difference in meaning between the real courtroom drama that transpired in 1953 and what is portrayed on film in 1960. The film gives us a version of truth, but it is not Pauline Dubuisson’s truth. Pauline was a relatively reserved woman and a serious medical student with a complicated wartime past. La Vérité, set in 1960, omits all the backstory that explains much of Pauline’s life trajectory. Dominique, the stand-in for Pauline in the film, is a simple party girl who seems, if not unintelligent, certainly not intellectual. She joins her sister, a talented violinist, in Paris, because Dominique does not get along with her parents. Once set free in the city, she becomes enthralled with a beatnik culture that did not exist in Pauline’s day. Dominique can’t hold her lover’s attention because classical music bores her and yet the object of her affection is studying to be a conductor. Her ravenous sexual appetite is on full display as she floats from lover to lover and then descends into prostitution once Gilbert rejects her. Described by one critic as a cross between a slut and Little Bo Peep, Dominique’s sexual allure is on full display in her first encounter with Gilbert when he finds her nude under a sheet, wiggling to Latin music in pre-coital delight.[6] One can actually sense Teillier’s arousal, and Frey’s for that matter, since he and Bardot began an affair during the making of the film.

Perhaps where film and life both intersect and diverge is in the fact that in each case female sexuality and power are on trial. As spectators we view Pauline and Dominique through the disapproving gaze of older men such as the prosecuting attorney, René Floriot in real life and Maître Épavier (played by Paul Meurisse) in the film. Both condemn female agency in a post-war world where female sexuality needs to be brought back under control if the pre-war traditional woman is to be resurrected. But the emotional heart of the film is generational angst, the profound discomfort of Clouzot and men of his generation, with Left Bank beatnik culture and its rejection of pre-war bourgeois values. Spectators at the trial consistently refer to Dominique as a “garce” and “tarte.” Even her own defense attorney asks his colleague if Dominique didn’t look too much like a “putain” for her first day in court. The colleague replied that there is no hiding good looks, a verbal bow to Bardot’s beauty in a film created especially for her.[7] La Vérité is about a decade, the 1960s, that had not happened yet, but the shape of which Clouzot could already discern in the youth culture of Paris. He did not like what he saw, and the film, far from being a celebration of youth and sexual liberation, is suffused with a fear of it. It is a dark film, a true “film noir” made at a time when filmmakers were moving on to a new genre, “New Wave Cinema,” that Clouzot also roundly rejected.

Dominique’s Paris is far removed from that of Pauline and in La Vérité the woman on trial, as much as Dominique, is Bardot herself, the embodiment of unleashed sexuality projected on the screen at a time when the actress was at the height of her iconic popularity and provocative allure. Everyone rejects Dominique in the film, her sister, her lover, even her friends to the point where her only escape is suicide which brings the trial (and film) to an end in circumstances different from the conclusion of Pauline’s. In the dark gloom of traditional French cinema, Clouzot captured the need to identify and punish female transgressors of cultural norms. In fact, no one in the film from Dominique’s generation, except, perhaps, her staid sister, escapes condemnation as insouciant, lazy, and promiscuous – not “serious” in the French sense of the word. But Clouzot reserved a special animus for Dominique and all she represented. Stories even circulated that as director Clouzot got Bardot drunk and slapped her around to elicit the performance he wanted near the end of the film in which Dominique kills her lover. In her memoirs Bardot remembered the director as negative and hostile.[8] But the genie was out of the bottle, and women rebelling against patriarchy had only just begun. Even so, this scenario was far removed from the real life of Pauline Dubuisson who was driven not by sexual liberation but rather by wartime trauma and mental anguish, subjects never explored in the film. By 1960 the horror of World War II had begun to fade or was thoroughly repressed, and Clouzot saw no need to engage it, since his Dominique would have been only a tiny girl during the war.

Perhaps one reason Clouzot updated the chronology in which the drama in La Verité unfolds had to do with his own wartime transgressions. During most of the war, Clouzot was an executive at Continental Films, a German owned company associated with Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda for the Nazi state. German capital financed the company and its films making Clouzot an economic collaborator, not unlike André Dubuisson, and one whose wartime films did not portray the French in the best light, (Le Corbeau, 1943, for example).[9] On October 17, 1944 a purging committee known as the Commission d’épuration du comité de libération du cinema français listed Clouzot as one of eight directors guilty of collaboration and barred him from filmmaking for three years, a minor form of “national indignity.”[10] It is thus no surprise that moralizing within La Verité also condemns the French legal system and its authoritarian patriarchy that in the end cannot establish the truth about Dominique because the lawyers’ cynicism and sense of moral superiority over her prevents them from discerning her truth. It is left to the spectator to side with Dominique and understand that she truly loved Gilbert who actually used her for sexual gratification and then discarded her like a common whore causing her to come to his room that fateful day with the intent of killing herself, not him, in a true crime of passion. It is this aspect of La Verité and the power it extends to the viewer as witness that reveals Clouzot’s brilliance as a filmmaker.[11] Yet . . . despite Clouzot’s disdain for the legal profession, when it came to his assessment of Dominique, he shared more than he himself would have wanted to admit with the prosecutors and judges who condemned her. Ultimately, his was a male gaze profoundly uncomfortable with sexually or intellectually transgressive women.

Conclusion: The Masks of Pauline Dubuisson

Both the book and the film succeed as works of art, and both reveal truths, but neither fully captures Pauline Dubuisson’s story. Today it is clear that Dubuisson was a victim of Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome, deriving from her dysfunctional childhood, the experience of the German invasion and occupation of Dunkirk, and the sexual abuse that she suffered at the hands of older German men. Her story is steeped in gender inequity and it is likely no accident that the sole juror who voted to save her life during the trial was the only female member of the jury. La petite femelle captures the complexity of Pauline Dubuisson far better than La Verité but that is because despite the title of the film, Clouzot wasn’t interested in the real Dubuisson. In fact, he couldn’t even see her or perhaps didn’t want to. Not only does La Verité fail to unpack the complexities of post-war France but it also never succeeds in unmasking Pauline Dubuisson. Jaenada, by contrast, who recognizes this weakness in the film, achieves a much deeper understanding of Dubuisson, but he too underestimates the cultural gap that separates his own life and that of an adolescent girl caught in the trauma of wartime France.[12] The Liberation did not liberate Dubuisson, or women like her, and one wonders whether or not the 1960s really freed French women like Bardot from the gender biases that condemned female sexuality except when it was under the control of, and in the service of, male needs and desires.

Dubuisson’s crime continues to fascinate the French public. Jaenada’s book is now viewed as the authoritative account of her life and tragic end. On February 1, 2021, a French biopic realized by Philippe Faucon and starring Lucie Lucas as Pauline Dubuisson, aired on the television channel France 2. Entitled La petite femelle, the telefilm is based on a screenplay adapted from Jaenada’s book. The film unsurprisingly thus hews much more closely to his interpretation of Dubuisson than that of the La Vérité.[13] It is the most recent, but most likely not the last, rendering of Dubuisson’s story because the “real” Pauline Dubuisson, enigmatic and unfathomable to her friends and enemies alike, threatens to remain always just beyond the grasp of those seeking to comprehend her.

Philippe Jaenada, La petite femelle, Paris: Éditions Julliard, 2015.

Henri-Georges Clouzot, Director, La Verité, 1960, 128 min, b/w, France, Han Productions, C.E.I.A.P., Iéna Productions; New York: Criterion Collection 2019, DVD.

NOTES

- Dubuisson’s story has been recounted in a variety of formats, and the facts of her life are well known. We use the works here as well as the book under review to construct the narrative of her life. Jean Laborde, Amour, Que de Crimes (Paris: Gallimard, 1954), 251-316; Pierre Scize, Au Grand Jour des Assises: Yvonne Chevallier, Pauline Dubuisson, Marie Besnard, Gaston Dominici (Paris: Éditions Denoël, 1955), 51-88; Serge Jacquemard, L’affaire Pauline Dubuisson (Paris: Fleuve Noir, 1992); Laura James, The beauty defense: femme fatales on trial (Kent, Ohio: Kent University Press, 2020) 55-57; Jean Cau, “Pauline Dubuisson, la séductrice humiliée,” Paris Match, 31 août 2015, (accessed January 16, 2021), https://www.parismatch.com/Actu/Faits-divers/Pauline-Dubuisson-la-seductrice-humiliee-Dans-les-archives-de-Paris-Match-820717; Caroline Constant, “Télévision, Pauline Dubuisson, l’histoire tragique d’un être libre,” L’Humanité, February 1, 2021. (accessed February 6, 2021), https://www.humanite.fr/television-pauline-dubuisson-lhistoire-tragique-dun-etre-libre-699485; Sadrine Issartel, “L’histoire de Pauline Dubuisson et du meurtre qui l’a toujours poursuivie,” Slate.Fr, 7 août 2017 (accessed February 6, 2021), http://www.slate.fr/story/149535/pauline-dubuisson.

- Philippe Jaenada, La petite femelle (Paris: Éditions Julliard, 2015); La Vérité, directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1960, (New York: Criterion Collection, 2019), DVD ; One can listen to Jaenada discuss La petite femelle on Philippe Jaenada: “pieces à conviction,” France Culture, 5 mars 2017, (accessed February 6, 2021), https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/une-histoire-particuliere-un-recit-documentaire-en-deux-parties/philippe-jaenada-pieces.

- Gayle K. Brunelle and Annette Finley-Croswhite, Murder in the Métro: Laetitia Toureaux and the Cagoule in 1930s France (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010); Idem., Assassination in Vichy: Marx Dormoy and the Struggle for the Soul of France (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020).

- A classic work on this issue of objectivity is Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question and the American Historical Profession, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

- Jaenada, 670.

- Herbert Feinstein, “My Gorgeous Darling Sweetheart Angels: Brigitte Bardot and Audrey Hepburn.” Film Quarterly 15, no. 3 (Spring 1962), 66.

- Christopher Lloyd, Henri-Georges Clouzot (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 152.

- Brigitte Bardot, Initiales B.B.: mémoires (Paris: Grasset, 1996), 242; Dan Yakir, “The Wages of Film,” Film Comment, 17, no. 6 (November-December, 1981), 39.

- Lloyd, 30.

- Lloyd, 30-31; Patrick Brion, “Réhabiliter Clouzot,” Revue des Deux Mondes, Octobre, 1991, 190-96.

- Ginette Vincendeau, “Women on Trial,” Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1960, (New York: Criterion Collection, 2019), Essay Insert; Roger Régent, “Les Seigneurs,” Revue des Deux Mondes, Janvier, 1961), 163.

- Jaenada, 666.

- La petite femelle, France 2, (accessed February 6, 2021), https://www.france.tv/france-2/la-petite-femelle/