Martha Hannah

University of Colorado, Boulder

When Ernest Pérochon published Les Gardiennes in 1924, the novel praised the enterprise of rural French women who had for the duration of the First World War set themselves the arduous tasks of working the land, securing the harvest from one year of hardship to the next, and maintaining the patrimony left in their care by the men who went to war. Now, almost a hundred years later, Xavier Beauvois’s quietly beautiful but somewhat problematic film returns to Pérochon’s text, capturing exquisitely the loveliness of the French countryside, the agony of wartime bereavement, and the resolve of rural women. But the film is as interesting for how it deviates from the novel, as it is illuminating in how it captures visually the character of a French village traumatized and ultimately transformed by the war.

When Ernest Pérochon published Les Gardiennes in 1924, the novel praised the enterprise of rural French women who had for the duration of the First World War set themselves the arduous tasks of working the land, securing the harvest from one year of hardship to the next, and maintaining the patrimony left in their care by the men who went to war. Now, almost a hundred years later, Xavier Beauvois’s quietly beautiful but somewhat problematic film returns to Pérochon’s text, capturing exquisitely the loveliness of the French countryside, the agony of wartime bereavement, and the resolve of rural women. But the film is as interesting for how it deviates from the novel, as it is illuminating in how it captures visually the character of a French village traumatized and ultimately transformed by the war.

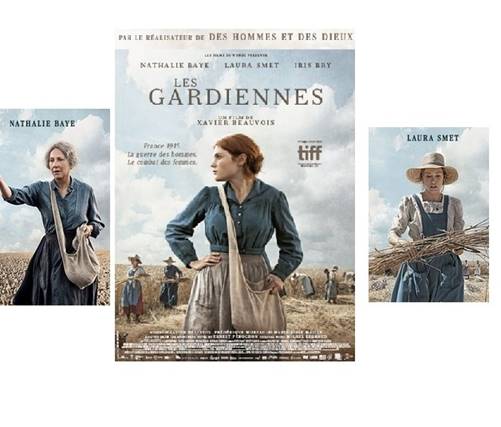

Situated in the village of Sérigny in the bocage region of western France, Les Gardiennes tells the rich, complicated, and tragic story of how the Misanger family, led by its indomitable matriarch, Hortense, struggled, suffered, persevered, and ultimately triumphed (albeit at considerable cost to its moral integrity) during the Great War. Hortense, played in the film by Nathalie Baye, is a formidable character, not to be crossed. After her two sons and son-in-law leave for war, she takes charge of the management and daily chores of the family farm. Her husband, Claude, is relegated in the film (but less so in the novel) to the role of bystander, either unable or unwilling to return to the fields; her daughter, Solange, lacks her mother’s steely resolve. When the only available hired men prove less than capable, Hortense hires a young woman to help plant and harvest the crops, tend to the cattle, and care for the horses. Francine (played by Iris Bry) proves a reliable, loyal, and indefatigable worker: an orphan who learned early the nature of hard work, Francine finds in the Misanger household something close to the family she had never known.

Situated in the village of Sérigny in the bocage region of western France, Les Gardiennes tells the rich, complicated, and tragic story of how the Misanger family, led by its indomitable matriarch, Hortense, struggled, suffered, persevered, and ultimately triumphed (albeit at considerable cost to its moral integrity) during the Great War. Hortense, played in the film by Nathalie Baye, is a formidable character, not to be crossed. After her two sons and son-in-law leave for war, she takes charge of the management and daily chores of the family farm. Her husband, Claude, is relegated in the film (but less so in the novel) to the role of bystander, either unable or unwilling to return to the fields; her daughter, Solange, lacks her mother’s steely resolve. When the only available hired men prove less than capable, Hortense hires a young woman to help plant and harvest the crops, tend to the cattle, and care for the horses. Francine (played by Iris Bry) proves a reliable, loyal, and indefatigable worker: an orphan who learned early the nature of hard work, Francine finds in the Misanger household something close to the family she had never known.  She also finds love, when the handsome, unattached, youngest son, Georges, comes home on leave. A romance between her beloved son and a young woman plucked from the poorhouse is not, however, something Hortense will tolerate: if Georges is to marry, he will marry the not-nearly-as-lovely Marguerite who at least will bring resources into the family, reinforcing the value of the family lands and securing the patrimony for the next generation. Unaware that Francine has accumulated several hundred francs in savings, more than enough to make her a good match, Hortense purposefully poisons the romance by suggesting to Georges that Francine is, in fact, nothing but a strumpet, all too ready to share her favors with the brash, loud-talking American troops biding their time before being sent into action on the Western Front.

She also finds love, when the handsome, unattached, youngest son, Georges, comes home on leave. A romance between her beloved son and a young woman plucked from the poorhouse is not, however, something Hortense will tolerate: if Georges is to marry, he will marry the not-nearly-as-lovely Marguerite who at least will bring resources into the family, reinforcing the value of the family lands and securing the patrimony for the next generation. Unaware that Francine has accumulated several hundred francs in savings, more than enough to make her a good match, Hortense purposefully poisons the romance by suggesting to Georges that Francine is, in fact, nothing but a strumpet, all too ready to share her favors with the brash, loud-talking American troops biding their time before being sent into action on the Western Front.

Two themes emerge as dominant motifs: rural France succeeded brilliantly in its mission to preserve and, indeed, enrich the land; and the arrival of American troops unsettled the social and moral foundations of village life. Over the course of the war, Hortense and Solange prove extraordinarily adept at maintaining the farm, increasing the farm’s crop yields, mechanizing the harvest, and augmenting their cattle stock. At the beginning of the war, the women of Sérigny go into the fields with scythes; by the end, they are maneuvering a mechanical harvester. Rural France in this telling prospers during the war, becoming more productive as it becomes more modern. This story of rural prosperity and modernization has the happy effect of applauding the resolve of France’s rural women, but it overlooks a more prevalent reality: the hard work of these resolute women notwithstanding, most of rural France did not prosper during the war. Hortense’s ability to add to the farm’s cattle stock was as unusual as it was admirable; Solange’s acquisition of a tractor and a harvester, equally so. In much of rural France land lay fallow for lack of manpower; crop yields inevitably declined; and France became dependent in ways it had never been before on imported food. By 1917, the wheat crop was only half as plentiful as that of 1914, and the army, having requisitioned well over two million cattle, had reduced the supply of animal fertilizer, on the one hand, and milk, on the other.[1] There was no food crisis in France comparable to that of Germany or Austria, in part because France was able to import food from North America, but rural French soldiers worried incessantly in the last year of the war about their families’ ability to feed themselves.

As the film explains, Solange acquires the farm’s modern equipment at fire-sale prices because the Americans simply leave it behind when they return home. But if Americans bring with them the prosperity of modern life, they also inject the germ of moral dissolution into the very heartland of la France profonde. Or so Hortense fears. When she comes to suspect that Solange is allowing herself to be seduced by the “Sammies” who congregate near Sérigny, Hortense acts quickly and decisively to quiet her neighbors’ wagging tongues, to save the honor of her family, and to protect Solange (and her marriage) from her husband’s righteous anger. Hortense decides to sacrifice Francine and her reputation on the altar of family respectability. Letting Georges know (or believe) that Francine is a faithless flirt would simultaneously protect Solange from unseemly innuendo and end Georges’ romantic attachment to a woman not worthy of his affections. That Francine is entirely innocent is beside the point. Hortense’s deception proves decisive: Georges spurns Francine, unaware that she is pregnant with his child, and marries the blameless Marguerite. Francine loses her job, finds refuge in the household of a war widow, and resolves to raise her son on her own. All because of the Americans.

As the film explains, Solange acquires the farm’s modern equipment at fire-sale prices because the Americans simply leave it behind when they return home. But if Americans bring with them the prosperity of modern life, they also inject the germ of moral dissolution into the very heartland of la France profonde. Or so Hortense fears. When she comes to suspect that Solange is allowing herself to be seduced by the “Sammies” who congregate near Sérigny, Hortense acts quickly and decisively to quiet her neighbors’ wagging tongues, to save the honor of her family, and to protect Solange (and her marriage) from her husband’s righteous anger. Hortense decides to sacrifice Francine and her reputation on the altar of family respectability. Letting Georges know (or believe) that Francine is a faithless flirt would simultaneously protect Solange from unseemly innuendo and end Georges’ romantic attachment to a woman not worthy of his affections. That Francine is entirely innocent is beside the point. Hortense’s deception proves decisive: Georges spurns Francine, unaware that she is pregnant with his child, and marries the blameless Marguerite. Francine loses her job, finds refuge in the household of a war widow, and resolves to raise her son on her own. All because of the Americans.

The American theme is not only central to the tragic denouement of Les Gardiennes but, potentially at least, a sore point for American audiences. The film, like the novel, is set in the bocage region of Deux-Sèvres, where Ernest Pérochon grew up. Located in the distant hinterland of Nantes, the villagers of Sérigny might indeed have come in contact with American troops from late 1917 onwards (although the definitive history of the American Expeditionary Force in the region suggests that the “Sammies” rarely ventured far beyond the city-limits of Nantes and Saint-Nazaire).[2] But if any French villagers had regular contact with the arriving Americans, they would have lived here in western France, close to the central ports of disembarkation for the AEF. Until the summer of 1918, many of the doughboys who made their way across the Atlantic remained well clear of the fighting lines, apparently not doing much to defeat the German enemy. The presence of large numbers of American troops, lollygagging behind the lines for months on end, provoked the anger and jealousy of rank and file French soldiers. Georges expresses the poilus’ contempt for the comfortably placed American soldiers, berating them for doing nothing but drink, flirt, and spend unseemly amounts of money while he and his compatriots suffer through a fourth year of misery and murderous shellfire.

The American theme is not only central to the tragic denouement of Les Gardiennes but, potentially at least, a sore point for American audiences. The film, like the novel, is set in the bocage region of Deux-Sèvres, where Ernest Pérochon grew up. Located in the distant hinterland of Nantes, the villagers of Sérigny might indeed have come in contact with American troops from late 1917 onwards (although the definitive history of the American Expeditionary Force in the region suggests that the “Sammies” rarely ventured far beyond the city-limits of Nantes and Saint-Nazaire).[2] But if any French villagers had regular contact with the arriving Americans, they would have lived here in western France, close to the central ports of disembarkation for the AEF. Until the summer of 1918, many of the doughboys who made their way across the Atlantic remained well clear of the fighting lines, apparently not doing much to defeat the German enemy. The presence of large numbers of American troops, lollygagging behind the lines for months on end, provoked the anger and jealousy of rank and file French soldiers. Georges expresses the poilus’ contempt for the comfortably placed American soldiers, berating them for doing nothing but drink, flirt, and spend unseemly amounts of money while he and his compatriots suffer through a fourth year of misery and murderous shellfire.

In its portrayal of Georges’s animosity towards the newly-arrived Americans, Les Gardiennes is well grounded in historical reality. As the postal censors observed in 1918, it was only when the Americans moved into combat positions in the summer of 1918 that French soldiers abandoned their scorn and disdain in favor of praise and appreciation for their new allies.[3] It is, however, a theme most likely to generate a visceral reaction in American audiences: how dare the film-makers (not to mention the poilus) not recognize and applaud the invaluable role the Americans played in the war? How can they be so ungrateful? For an audience persuaded – as a recent New York Times article reiterates – that the Americans “won the war” these scenes of American indolence and French acrimony sit uncomfortably with received wisdom.[4] This, at least, is a lesson I took away from a screening of the film this summer. I had been invited to lead a post-screening discussion of the film with an audience of well-read and well-traveled Boulder locals. They were thoughtful, curious, and – in the main – appreciative of the film. They were, however, anything but appreciative of how the film depicted the doughboys of the American Expeditionary Force. No one left the film with an undiluted admiration for Hortense, her valiant efforts to preserve the family patrimony notwithstanding; but neither did anyone try to understand why a generation of young French men, who endured heavier casualties than any of their allies, whose homeland was devastated by war, and whose womenfolk were, they feared, all too susceptible to the Sammies’ allure, would have felt bitterness and resentment towards these late-arriving allies. Because Les Gardiennes presents American troops in a way that is unfamiliar to and probably objectionable to American students, this point of cultural discomfort constitutes an excellent starting point for classroom conversation.

In its portrayal of Georges’s animosity towards the newly-arrived Americans, Les Gardiennes is well grounded in historical reality. As the postal censors observed in 1918, it was only when the Americans moved into combat positions in the summer of 1918 that French soldiers abandoned their scorn and disdain in favor of praise and appreciation for their new allies.[3] It is, however, a theme most likely to generate a visceral reaction in American audiences: how dare the film-makers (not to mention the poilus) not recognize and applaud the invaluable role the Americans played in the war? How can they be so ungrateful? For an audience persuaded – as a recent New York Times article reiterates – that the Americans “won the war” these scenes of American indolence and French acrimony sit uncomfortably with received wisdom.[4] This, at least, is a lesson I took away from a screening of the film this summer. I had been invited to lead a post-screening discussion of the film with an audience of well-read and well-traveled Boulder locals. They were thoughtful, curious, and – in the main – appreciative of the film. They were, however, anything but appreciative of how the film depicted the doughboys of the American Expeditionary Force. No one left the film with an undiluted admiration for Hortense, her valiant efforts to preserve the family patrimony notwithstanding; but neither did anyone try to understand why a generation of young French men, who endured heavier casualties than any of their allies, whose homeland was devastated by war, and whose womenfolk were, they feared, all too susceptible to the Sammies’ allure, would have felt bitterness and resentment towards these late-arriving allies. Because Les Gardiennes presents American troops in a way that is unfamiliar to and probably objectionable to American students, this point of cultural discomfort constitutes an excellent starting point for classroom conversation.

Films are not monographs: they do not need to adhere exactly to the facts unearthed in archives. Nor, when they adapt a novel, do they need to be strict, unerring adaptations of the original text. To observe, therefore, that Beauvois’s cinematic rendition of Les Gardiennes provides an ending quite unlike that given in the novel is not necessarily a point of criticism. It is, however, worth pondering: why does he propose a fate for Francine so different from that suggested in the novel? And what does the new ending tell us about how contemporary France imagines the transformative effects of the Great War for women and for rural society? In both the novel and the film, Francine finds herself pregnant, alone, and abandoned by Georges. In both cases, she opts to keep her baby, rather than place him for adoption. She will not abandon her child in the way that she had been abandoned. In the novel, however, motherhood becomes her destiny: Francine imagines a future for herself as a fierce and determined mother, resolved to care for her child out of love, to be sure, but also out of a strong sense of self-preservation: her son will repay his mother’s love by caring for her and shielding her from the cruel aspersions of sanctimonious neighbors. For Pérochon – as for much of postwar France – motherhood was not only a young woman’s appropriate destiny but also her ultimate consolation. And, indeed (as Mary Louise Roberts reminded us in Civilization Without Sexes) even an unwed mother could garner the gratitude of a nation so sorely depopulated by the Great War. For Beauvois, however, motherhood is not enough. Francine does not shrink into the shadows of domestic employment, hoping that her baby will not disturb the sleep of her elderly employer. Rather, she cuts her hair and becomes a night club singer. One evening, while singing that “love is fragile and promises easy” to make and just as easily broken, she looks out into the audience and espies Georges. She now appears not as a mother devoted exclusively to the care of her child but as a modern woman earning her keep as a chanteuse with bobbed hair. This ending strongly suggests that the war marked a moment of cultural – as well as economic – transformation, the moment when rural France became truly modern. Without doubt, modernity did make inroads into rural France after 1919, but more slowly, I think, than Les Gardiennes would have us believe.

Films are not monographs: they do not need to adhere exactly to the facts unearthed in archives. Nor, when they adapt a novel, do they need to be strict, unerring adaptations of the original text. To observe, therefore, that Beauvois’s cinematic rendition of Les Gardiennes provides an ending quite unlike that given in the novel is not necessarily a point of criticism. It is, however, worth pondering: why does he propose a fate for Francine so different from that suggested in the novel? And what does the new ending tell us about how contemporary France imagines the transformative effects of the Great War for women and for rural society? In both the novel and the film, Francine finds herself pregnant, alone, and abandoned by Georges. In both cases, she opts to keep her baby, rather than place him for adoption. She will not abandon her child in the way that she had been abandoned. In the novel, however, motherhood becomes her destiny: Francine imagines a future for herself as a fierce and determined mother, resolved to care for her child out of love, to be sure, but also out of a strong sense of self-preservation: her son will repay his mother’s love by caring for her and shielding her from the cruel aspersions of sanctimonious neighbors. For Pérochon – as for much of postwar France – motherhood was not only a young woman’s appropriate destiny but also her ultimate consolation. And, indeed (as Mary Louise Roberts reminded us in Civilization Without Sexes) even an unwed mother could garner the gratitude of a nation so sorely depopulated by the Great War. For Beauvois, however, motherhood is not enough. Francine does not shrink into the shadows of domestic employment, hoping that her baby will not disturb the sleep of her elderly employer. Rather, she cuts her hair and becomes a night club singer. One evening, while singing that “love is fragile and promises easy” to make and just as easily broken, she looks out into the audience and espies Georges. She now appears not as a mother devoted exclusively to the care of her child but as a modern woman earning her keep as a chanteuse with bobbed hair. This ending strongly suggests that the war marked a moment of cultural – as well as economic – transformation, the moment when rural France became truly modern. Without doubt, modernity did make inroads into rural France after 1919, but more slowly, I think, than Les Gardiennes would have us believe.

Xavier Beauvois, Director, Les Gardiennes/The Guardians, 2017, 138 min, Color, France, Switzerland, Les Films du Worso, Pathé, France 3 Cinéma et al.

NOTES

- Michel Augé-Laribé, L’Agriculture pendant la guerre: Histoire économique et sociale de la Guerre mondiale, Publications de la Dotation Carnegie pour la paix internationale (Paris : Presses Universitaires de France, 1925), 56, 59.

- Yves-Henri Nouailhat, Les Américains à Nantes et Saint-Nazaire, 1917 – 1919 (Paris : Belles Lettres, 1972), 185.

- Jean Nicot, Les Poilus ont la parole: Dans les tranchées : lettres du front, 1917 – 1918 (Paris : Éditions Complexe, 1998), 429 – 431.

- Geoffrey Wawro, “How ‘Hyphenated Americans’ Won World War I: Nearly a quarter of the men sent to fight in Europe in 1918 were foreign-born,” New York Times, 12 September 2018.