Lisa Jane Graham

Haverford College

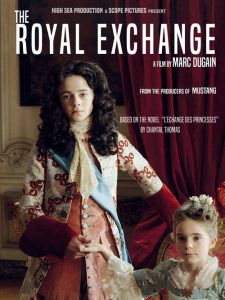

Marc Dugain’s 2018 film, L’échange des princesses, recounts a diplomatic episode at the start of Louis XV’s reign from the perspective of four children contracted in marriage to secure peace between France and Spain after a decade of war. The events unfold over four years (1721-1725). When Louis XIV died in 1715, the heir to the throne, his great-grandson, was five years old. The dying king had appointed his recently legitimized son, the duc de Maine, to share in the Regency government, wary of his nephew Philippe, duc d’Orléans. Philippe had the Paris Parlement annul Louis’s will and recognize his sole right to the Regency until the new king reached age 13. Eager to reinforce ties with Philip V (Louis XIV’s grandson) who had been installed on the Spanish throne after a bitter war of succession, and to insure that Philip V not revive his claims to the French throne as conservative elements in Spain and France wished him to, the Regent suggested an exchange of brides. This was all the more urgent since Spain, dissatisfied with the Treaty of Utrecht, had fought France and other European powers between 1718 and 1720. Orléans proposed that the 11-year old Louis XV marry the 3-year old Spanish Infanta, Anna Marie Victoria. In exchange, he offered his daughter, the 12-year old Louise Elisabeth, to the 14-year old heir to the Spanish throne, Don Luis, Prince of Asturias. The girls would strengthen bonds between the Bourbon branches by producing heirs to link the two dynasties, although clearly favoring the Regent’s junior branch.

The film is based on a novel by Chantal Thomas and Thomas collaborated with Dugain on the screenplay.[1] Some of the dialogue is lifted directly from the novel. The film replicates the novel’s episodic structure that moves back and forth between the French and Spanish courts. Although we follow the princesses on their journeys across borders, the story unfolds in the hermetic space of each court with no glimpse of the people over whom these children will reign.

The film begins in a dark bedchamber at Versailles in 1712. It is early morning and we glimpse a child asleep in an ornate bed surrounded by dozing attendants. The sound of knocking awakens the boy’s governess, Madame de Ventadour, who finds a cluster of dour physicians who inform her that the Duc de Bretagne, the boy’s older brother, has just died. This death leaves her young charge, the 2-year old duc d’Anjou, as sole heir to the throne since he has already lost his parents to the epidemic that has ravaged the court. When the doctors demand to treat the sleeping prince, Ventadour refuses to surrender her charge. She excoriates the men of science as “incompetents and assassins” and blames them for killing the boy’s family. This opening scene alerts the viewer to the specter of death that would haunt this boy and future king his entire life. It also establishes the battles that will be waged over and through childrens’ bodies in the minefield of court politics.

The film then jumps forward to 1719 when the 9-year old boy, Louis XV, returns to the abandoned palace under the tutelage of his uncle the Regent, Philippe duc d’Orleans. The child wanders through the marble corridors alone, staring at portraits of his ancestors. He embraces the bust of the mother he barely knew and is overcome with sadness. When he goes to bed that evening, he asks his tutor, François de Villeroy, Marshall of France, about conspiracies. He asks whether people kill children to steal their throne and Villeroy tells him that, sadly, history is full of such examples. He then asks Villeroy to tell him again about his parents, in particular his mother who illuminated the court with her presence. The boy observes that if his family had lived, “mon enfance aurait été la mienne,” (my childhood would have been my own).

This is a film about stolen childhood and the emotional toll it takes on its victims. A talented cast of actors captures the awkwardness of children thrust into adult roles and costumes as they search for approval and guidance. For example, early in the film, the camera lingers on Louis XV (Igor van Dessel) staring out a window and caressing his favorite cat. Villeroy announces the arrival of the Regent (Olivier Gourmt) and the boy implores his governor, “Can they wait? I have not finished my daydream.” (10:00-11:30) Alas, there is no time for daydreaming according to the Regent who is bent on “maintaining the peace” with Spain and needs the boy’s consent for the marriage proposal. The camera zooms in on the boy’s alarmed face as he tries to understand what is being asked and whether to agree. The camera follows his eyes as he scans the room of ministers for a clue of what to say. Finally, he winces and blurts out “oui” to escape this tense situation: he senses that his future is at stake but also that he is outnumbered and has no choice.

Chantal Thomas specializes in what might be called subaltern histories of the court as seen in previous novels about Louis XV’s “brothel” run by Madame de Pompadour at the Parc aux Cerfs, and the last days of Marie-Antoinette at Versailles in October 1789.[2] In both cases, Thomas used fiction to demystify the court as a locus of privilege and power through the eyes of someone who works there, a sex worker for the king or a reader to the queen. These girls from humble provincial families are outsiders who must learn the rules of protocol in order to survive. In L’Echange des princesses, Thomas mines this vein through two princesses shipped off to a foreign court at a young age. When the Regent informs his daughter of his plan, she is appalled by the idea and retorts, “I want to live.” She is old enough to understand that marriage is a death sentence for a princess. The Regent storms out of the room and leaves her with her grandmother, Liselotte, the Princess Palatine, who dispels any illusion of choice, “Princesses are born to be married and to produce heirs.” Even before their journeys, the girls have powerful enemies determined to thwart the alliance and sow distrust. They are prey for traps, a point reinforced in the film through recurring scenes of hunting, the royal sport par excellence. Both Dugain and Thomas suggest this passion for hunting reflected the bloodlust that defined the social constellation around the king.

The film shows us life at court through the eyes of children and teenagers and asks whether such categories even existed at the time. Thomas foregrounds this theme early in her novel, “These marriages are child’s play, but organized by adults, …Do such children even have a childhood to save? But who in that era could lay claim to a childhood?” [Ces mariages sont des jeux d’enfants, mais organisés par les adultes, … Ont-ils même une enfance à sauver, ces enfants-là? Mais qui à cette époque, a une enfance à revendiquer?”] (p. 35) The film suggests that childhood is a privilege of the modern era. As Thomas observes, there was no time for adolescence, “that wasteland of experience.” With luck, “one moved directly to adulthood whose two main tasks were work and reproduction.” (p.137) Once a princess turned thirteen, she was deemed fit for procreation.

Dugain offers an alternative perspective on the court from the one we generally see on screen. The elegiac soundtrack and luminous cinematography convey the pathos of privilege for royal children and the adults who cater to them. Jean de la Bruyère’s observation that “Life at court is a serious, melancholy game” seems especially poignant when applied to these four children.[3] Both the film and the novel remind us of the gulf that separates our own era from the eighteenth century’s attitudes toward children and childhood.

Thomas includes excerpts from letters written by the principal actors in this drama and draws on her familiarity with eighteenth-century sources including memoirs, gazettes and police reports. Like the film, her novel devotes more attention to the French side of the story perhaps because Versailles looms larger in our collective memory than either the Buen Retiro or the Escorial. As a novelist, Thomas gets inside her characters heads and hearts. She reveals the conflicting emotions that guide the protagonists: fear and hope, a desire to please and an instinct to resist, good manners and bad tempers. The film inevitably streamlines the characters and storyline to convey the main themes in under two hours. It contrasts the sweet and regal Infanta (Juliane Lepoureau) scorned by a haughty and indifferent Louis XV to the pouty and vulgar Louise Elisabeth (Anamaria Valtoromei) who mocks and rejects her dolt of a prince. Dugain turns some of the characters into caricatures including the mincing duc de Condé and the self-flagellating king of Spain, played with harrowing fervor by Lambert Wilson. The film reinforces tropes about evil and effeminate courtiers who mislead princes and the baroque rituals of the Spaniards compared to French sophistication.

Dugain contrasts the brightly lit French scenes to the somber interiors of the Spanish palace. At Versailles, the Infanta enjoys playing with dolls, boating on the canal, and running outdoors. She develops an instant bond with Liselotte who cultivates the girl’s love of nature, telling her “nature exalts us and gives us energy.” (44:40) Besides her governess, Madame de Ventadour, the Infanta has no adult allies at court until she meets Liselotte. Both women are relics of the previous reign. The scenes between Liselotte, played by the formidable actress, Andrea Ferriol, and the Infanta stand out for their ability to capture the bond forged across generations between these two foreign princesses. Liselotte displays tenderness and intelligence toward the child, and offers the young princess advice that she is too young to grasp, warning her that after the initial adulation, “the court bleeds us just like the doctors,” concluding “even though we are princesses, we are nothing but meat for marriage.”(53:00) The little girl will learn the full meaning of these words the hard way after her friend dies.

Dugain contrasts the brightly lit French scenes to the somber interiors of the Spanish palace. At Versailles, the Infanta enjoys playing with dolls, boating on the canal, and running outdoors. She develops an instant bond with Liselotte who cultivates the girl’s love of nature, telling her “nature exalts us and gives us energy.” (44:40) Besides her governess, Madame de Ventadour, the Infanta has no adult allies at court until she meets Liselotte. Both women are relics of the previous reign. The scenes between Liselotte, played by the formidable actress, Andrea Ferriol, and the Infanta stand out for their ability to capture the bond forged across generations between these two foreign princesses. Liselotte displays tenderness and intelligence toward the child, and offers the young princess advice that she is too young to grasp, warning her that after the initial adulation, “the court bleeds us just like the doctors,” concluding “even though we are princesses, we are nothing but meat for marriage.”(53:00) The little girl will learn the full meaning of these words the hard way after her friend dies.

Liselotte’s assessment is reinforced throughout the film where the princesses are reminded that their sole purpose is to produce heirs to secure the throne for their spouse. While we see Louis XV being tutored in geography, we learn that Louise Elisabeth does not know how to read and Thomas includes samples of the girl’s phonetically spelled letters to her father to illustrate the point. The pressure on Louise Elisabeth to consummate her marriage is relentless, with the duc de Saint-Simon reminding her that “The future of Europe is at stake here… you have an important responsibility.” Neither girl is ready for her reproductive tasks, either emotionally or physically. The surveillance of and speculation about their bodies is constant and inescapable, similar to the disciplinary impulse that Larry Woolf identifies in the letters between Maria Theresa and Marie-Antoinette after the latter’s marriage to Louis XVI.[4]

The film highlights the novel’s exploration of sex and death to illustrate the precarity of monarchies whose destinies rested on mortal bodies. We are constantly reminded that disease threatened to eradicate this alliance at any moment: Louise Elisabeth takes a detour to avoid plague but arrives in a swollen and feverish state in Spain. Soon after she consummates the marriage with Luis (after months of being repelled by him), her husband dies of smallpox. Her in-laws literally lock her up in the room hoping that she, too, will contract the disease and die. She is useless to them without their son. To their disappointment, Louise Elisabeth survives and the couple debates what to do with her. They decide to ship her back to France, remarking, “she serves no purpose here now.” She had been queen for seven months. Philip had abdicated in favor of his son in January 1724 and assumed the crown again in August. But Louise Elisabeth has no desire to return now that her father has died (on 15 February 1723). Saint-Simon tells her she has no choice, observing that “politics is often tied to mortality and there is nothing we can do about it.”

Thomas is unsparing in describing the diseases contracted by the two princesses and the treatments they endured. When Louise Elisabeth arrives in Spain after an arduous journey, her new family is shocked by her disfigurement and enraged that they have been sold damaged goods. In addition, the girl is rude and impious. Nonetheless, their dolt of a son is enamored with his betrothed. In the novel, Thomas suggests that they blame her for their son’s death and “they want to be rid of her, to send her back to France, not just as a source of scandal but the way one banishes a criminal from one’s sight, since one can’t remove him from the surface of the earth.” (p. 285) Thomas quotes a diplomat who refers to the 15-year old widow as “a bundle of dirty laundry,” a hint of what awaits her back in Paris. Dugain eliminates these backstories in the interest of narrative efficacy while hewing close to the novel’s empathy for how these girls were mistreated and assessed like commodities with fluctuating value depending on performance.

The death of King Luis undermines the Regent’s strategy and energizes factions that had opposed it from the start. With the loss of her brother at the end of August 1724, the six-year old Infanta’s position is increasingly vulnerable in this hostile court. Unable to grieve the brother she has lost, she senses that forces are colluding to separate her from her beloved prince. Despite her charms, her tender age makes her a risk given the capricious temperament of her father who may try to claim the throne. Condé warns Louis XV that the doctors have examined her and deemed her unfit for procreation. The pressure mounts to break the marriage contract with Cardinal Fleury, the young king’s new tutor, admonishing the king, “you need an heir as soon as possible.” (1:20) Thomas reconstructs the vilification campaign that targeted this girl with no friends except her governess to protect her. Physicians and courtiers scrutinize her body mercilessly for defects that will justify returning her to Spain as unfit for procreation. Louis XV appears passive in response to these machinations, indifferent to the princess who adores him despite his aloofness, but unwilling to break the contract. In the novel, Thomas revisits themes that she explored in her study of the attacks on Marie Antoinette who was the pawn in a controversial reversal of alliances.[5]

The specter of death that stalks these children is balanced by the discovery and disciplining of sex. Except for the Infanta, all three children are going through puberty. They are by turns curious and fearful about these stirrings of desire. The film illustrates the novel’s exploration of sexual education and sexual policing at court. Both Thomas and Dugain evoke the confusion of these teenagers navigating a culture in which sex is simultaneously solicited and regulated. It is hard to decipher the hidden rules. All four children are instilled with a duty to use their bodies for procreation. Yet, they must learn the limits of permissible behavior and desires. In Spain, the awkward Don Luis is caught masturbating with the portrait of Louise Elisabeth while he awaits her arrival. The film portrays this scene well when the boy is surprised in his bed by an attendant who removes the portrait and reminds him, “some restraint would please God.” (19:00) When he is finally permitted to share a bed with his wife, he receives an anatomy lesson with a wooden model whose pelvis opens to reveal the womb (48:50). The boy closes the pelvis as though he does not want the anatomy to interfere with his fantasies. That night, Louise Elisabeth recoils in horror from his touch and screams, “No. Don’t ever touch me again.” (50:00) Her refusal to consummate the marriage further isolates her from her in-laws and endangers the peace plans.

The film captures the confusion of puberty and the lack of guidance for these children. Louis XV is surrounded by older boys with more sexual experience. He asks the duc de Condé how carnal pleasures compare to those of hunting to which Condé replies, “more intense but also briefer.” Later, he catches two of his friends caressing each other over a chessboard and storms out of the room. It is not clear why he is alarmed by what he sees. The film suggests the challenges of navigating intimacy in this environment suffused with pleasures. Although nobody offers to educate the young king, he learns the rules by observation and interrogation. One night he glimpses his close friend, the marquis de Boufflers, being whisked away in a carriage. Fleury explains that Boufflers was caught by his parents “in the midst of an act against nature.”[6] Louis XV remarks that Boufflers had taught him certain acts but that he could not recall whether he enjoyed them. He is more hurt by the loss of his friend than by the scandal for which he is banished. He turns to Fleury for advice but Fleury avoids answering by claiming the ignorance that comes with celibacy. The film establishes a parallel lesson with Louise Elisabeth who discovers friendship and sex with her maids. Her favorite servant, la Quadra, teaches her “there are far subtler pleasures” that won’t lead to pregnancy. Thomas suggests that the princess scandalized the court by displaing her lesbian relations openly. The film treats the episode more ambiguously as a phase of experimentation and a refuge from the hostile court. Don Luis discovers his wife in bed with her maid and dismisses her. When he finally earns access to her bed, the prince asks if “it is better than with a woman” and she replies, “too soon to know.” The stakes of same-sex dalliances in both cases are political not moral since these bodies must procreate to secure the Bourbon alliance. The film suggests that same-sex relations provided an outlet for emotional intimacy as much as carnal release. These children are lonely and besides the Infanta, they spend little time in the games and activities we associate with childhood today. They are sexual and sexualized subjects before they have given up their dolls and dogs.

I would like to conclude this review with the one scene in the film where a princess glimpses someone from the world outside of the court. During her coach journey to Spain, Louise Elisabeth stops at one point to relieve herself in the woods (27:40). She is dressed like a princess in a rose taffeta gown with a white ermine stole fastened around her shoulders. She walks far enough away to shield herself from view and then squats near a tree. The camera zooms to the sky overhead, a suggestion of a flight that is denied her. When the camera returns to the woods, Louise Elisabeth stands up and sees a peasant girl in tattered clothes standing with a donkey a few yards away. She looks like a fairytale princess to the peasant. The accidental proximity renders them speechless. The two girls lock eyes as they peer into each other’s world. Louise Elisabeth is transfixed by this vision. The film suggests that she is asking herself whether she would be happier, or freer, in this girl’s world. Nonetheless, we sense that whatever the social divide, both girls were constrained to labor albeit in different ways. Once the coachman discovers the peasant, he shoos her away with a wave of the hand and escorts the princess back to her carriage. His reaction suggests that this exposure to the hardships that lay outside the court was more dangerous than the epidemics then ravaging the countryside. Moreover, the scene hints at a central theme of the film concerning the bonds forged across borders and generations, between girls traded as commodities and subordinated to their male counterparts. Thus, it should provoke a lively classroom debate about whether we can write a feminist and intersectional history of the court, which recognizes the potential for emancipation from within the corridors of privilege and power.

Marc Dugain, Director, L’échange des princesses/The Royal Exchange, 2017, 100 min, Color, France, Belgium, UK, High Sea Production, Scope Pictures, Motion Partners et al.

NOTES

- Chantal Thomas, L’Echange des princesses (Seuil, 2013). There is an English edition available, The Exchange of Princesses, translated by John Cullen (Other Press, 2015).

- Chantal Thomas, Le Testament d’Olympe (Points, 2011) and Les Adieux à la Reine (Seuil, 2002). The latter was made into a film by Benoît Jacquot in 2012.

- Jean de la Bruyère, Les caractères (1687). Characters, translated by Jean Stewart (New York: Penguin Books, 1970), p.243.

- Larry Woolf, “Hapsburg Letters: The Disciplinary Dynamics of Epistolary Narrative in the Correspondence of Maria Theresa and Marie-Antoinette” in Dena Goodman, ed. Marie Antoinette: Writings on the Body of a Queen (Routledge, 2013): 25-44.

- Chantal Thomas, The Wicked Queen. The Origins of the Myth of Marie-Antoinette, translated by Julie Rose (Zone Books, 2001).

- This refers to the “affaire des palissades” early in Louis XV’s reign and concerns about the king’s indifference to women as compared to his male hunting companions. See Maurice Lever, Louis XV, libertin malgré lui (Payot, 2007) and Jeffrey Merrick, “Sodomitical Scandals in the 1720s,” Men and Masculinities 1:4 (1991): 373-92.