Donald Reid

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Viewers of The Battle of Algiers do not forget the scenes of the three young women who set bombs in downtown Algiers. Yet, as Danièle Djamila Amrane-Minne, a bombiste who hid with Zohra Drif in the Casbah, and later an historian of women in the National Liberation Front (FLN), observes, there is a “complete absence of speaking roles for women activists” in the film.[1] Inside the Battle of Algiers, Zohra Drif’s engaging memoir of her youth gives a voice to these women.

Daughter of a judge in the Islamic courts and of a mother who instilled in her a keen awareness of French exploitation of Algeria, Drif left home as a young teen to go to Algiers for high school and then to university to study law. After the war of independence began in November 1954, Drif and her high school and university classmate, Samia Lakhdari, assiduously sought out the FLN and its armed wing, the ALN, the Army of National Liberation, eschewing less radical student organizations. They initially distributed funds to the families of FLN/ALN combatants who had been arrested or had died in the struggle. However, the pair, steeped in films and stories of the French Resistance, wanted a more active role. They convinced the movement’s leaders and began to work with Yacef Saâdi, an ALN officer in the Zone Autonome d’Alger (ZAA), whom Drif refers to as “El Kho” (Brother) throughout the book. Lakhdari was a descendant of the nationalist hero Emir Abdelkader through her mother, Mama Zhor, a woman who actively supported the cause. Mama Zhor even accompanied her daughter when she set a bomb at the Cafétéria café, although The Battle of Algiers left the mother out, perhaps because Lakhdari and Drif took this initiative without informing Saâdi.

Daughter of a judge in the Islamic courts and of a mother who instilled in her a keen awareness of French exploitation of Algeria, Drif left home as a young teen to go to Algiers for high school and then to university to study law. After the war of independence began in November 1954, Drif and her high school and university classmate, Samia Lakhdari, assiduously sought out the FLN and its armed wing, the ALN, the Army of National Liberation, eschewing less radical student organizations. They initially distributed funds to the families of FLN/ALN combatants who had been arrested or had died in the struggle. However, the pair, steeped in films and stories of the French Resistance, wanted a more active role. They convinced the movement’s leaders and began to work with Yacef Saâdi, an ALN officer in the Zone Autonome d’Alger (ZAA), whom Drif refers to as “El Kho” (Brother) throughout the book. Lakhdari was a descendant of the nationalist hero Emir Abdelkader through her mother, Mama Zhor, a woman who actively supported the cause. Mama Zhor even accompanied her daughter when she set a bomb at the Cafétéria café, although The Battle of Algiers left the mother out, perhaps because Lakhdari and Drif took this initiative without informing Saâdi.

What did these women offer the liberation movement? Being among the few Algerian students in elite French schools, they could look and act European and this allowed them to pass effortlessly in the highly segregated society. Drif and Lakhdari believed that the war should be taken to the pied-noir population in Algiers, and that they had the ability to do this. Djamila Bouhired, a fearless French speaker from the Casbah, joined them. The young women picked targets for the bombings and did extensive reconnaissance. Drif chose the Milk Bar because it embodied the “offensive carefree attitudes” and “shameful indifference to our woes” she saw in the pieds-noirs. (110) Drif and Lakhdari selected their targets for precisely the qualities that shock the viewer of The Battle of Algiers.

What did these women offer the liberation movement? Being among the few Algerian students in elite French schools, they could look and act European and this allowed them to pass effortlessly in the highly segregated society. Drif and Lakhdari believed that the war should be taken to the pied-noir population in Algiers, and that they had the ability to do this. Djamila Bouhired, a fearless French speaker from the Casbah, joined them. The young women picked targets for the bombings and did extensive reconnaissance. Drif chose the Milk Bar because it embodied the “offensive carefree attitudes” and “shameful indifference to our woes” she saw in the pieds-noirs. (110) Drif and Lakhdari selected their targets for precisely the qualities that shock the viewer of The Battle of Algiers.

In preparation, Drif and Lakhdari had their hair and makeup done at a chic salon near the Milk Bar. On the morning of the bombings, September 30, 1956, the pair took up the stylist’s offer and returned for touch ups. The pied-noir press initially reported that the bombs had been set by European women and named a Communist, Raymonde Peschard, a blonde like Drif, as the perpetrator at the Milk Bar. Pieds-noirs did not believe that native women could pull off such feats.  Preparing for another mission, Drif changed her appearance to avoid making more trouble for Peschard, who later died as an FLN fighter in the maquis.

Preparing for another mission, Drif changed her appearance to avoid making more trouble for Peschard, who later died as an FLN fighter in the maquis.

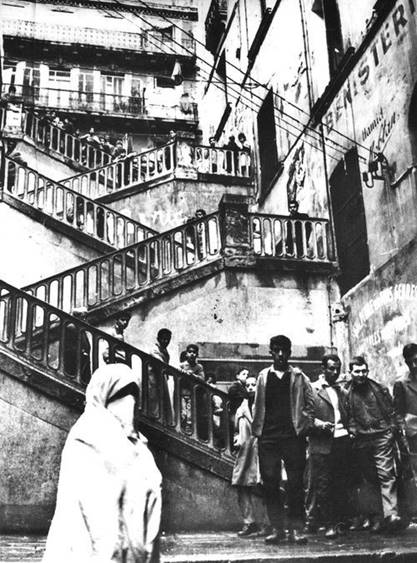

After the bombing, Drif and her fellow female bombistes hid in safe houses in the Casbah, a neighborhood that Drif had feared as a world of brothels and gambling, but came to know as a rich and diverse site of Algerian sociability and solidarity. In late January 1957, the FLN called a general strike to show popular support for their cause when the United Nations met to discuss the situation in Algeria. Drif and Bouhired went from terrace to terrace in the Casbah talking to women, explaining the strike and rallying their support.

Before her capture in September 1957, Drif began organizing women in extensive clandestine neighborhood committees to engage in protests, to denounce the arrests and disappearances of militants, to aid the families of those arrested, and to gather intelligence. As Neil McMaster recognizes, Drif’s organization “offered a formidable potential for the regeneration” of ZAA forces after the arrest of Drif and Saâdi. This spurred army efforts to penetrate Algerian women’s social world. [2] Drif thought that popular mobilization and protest, drawing largely on women and their networks, was crucial to the struggle, but it appears in The Battle of Algiers only at the very end of the film, in the demonstrations of December 11, 1960.

Before her capture in September 1957, Drif began organizing women in extensive clandestine neighborhood committees to engage in protests, to denounce the arrests and disappearances of militants, to aid the families of those arrested, and to gather intelligence. As Neil McMaster recognizes, Drif’s organization “offered a formidable potential for the regeneration” of ZAA forces after the arrest of Drif and Saâdi. This spurred army efforts to penetrate Algerian women’s social world. [2] Drif thought that popular mobilization and protest, drawing largely on women and their networks, was crucial to the struggle, but it appears in The Battle of Algiers only at the very end of the film, in the demonstrations of December 11, 1960.  Viewers of The Battle of Algiers, like the FLN and the French state at the time, are surprised by these formidable protests. By focusing solely on the bombings and the repression of the bombers, the film largely ignores the activism of women that Drif spurred and that was a prelude to the demonstrations more than three years after her arrest.

Viewers of The Battle of Algiers, like the FLN and the French state at the time, are surprised by these formidable protests. By focusing solely on the bombings and the repression of the bombers, the film largely ignores the activism of women that Drif spurred and that was a prelude to the demonstrations more than three years after her arrest.

The other important element of Drif’s account lacking in The Battle of Algiers is the sorority created by Drif and the women with whom she fought. Drif’s education enabled her to participate actively in debates with male leaders, and handle correspondence, write tracts, and prepare reports for the FLN and its press. When the French arrested Bouhired in April 1957, Drif immediately set out to find her a lawyer, without first consulting Saâdi. A lawyer herself, Drif explains the success of the lawyer she found, Jacques Vergès, whose creation of a show trial challenged the colonial republic. Just as the women are more three-dimensional figures than appear in The Battle of Algiers, the same is true for the lumpenproletarian-turned-revolutionary Ali la Pointe: “the most generous one, the most human and fraternal one” in the group (187).

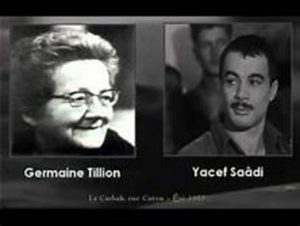

The most important scenes missing from The Battle of Algiers are the two visits of the ethnologist and deported resister Germaine Tillion to Saâdi, Drif, Ali la Pointe and the female bombmaker Hassiba Ben Bouali in hiding in July and in August 1957. Participants’ accounts of these meetings differ in details, but more importantly in the interpretation of what was going on. [3] Tillion says that Drif spoke little, particularly in the first meeting, which she attributed to the powerlessness of young women in Algerian society. However, Tillion saw Saâdi experiencing a “crisis of conscience” and expressing “evident remorse,” with tears in his eyes, as he spoke of the bombings. When Tillion told the group that they were killers, Saâdi agreed, saying that they had no choice. For “exclusively moral reasons,” Tillion believed, he reached an agreement with her that if the government ended executions of arrested militants, Saâdi’s group would launch no more attacks which targeted civilians. Although Tillion was unable to get the government to stop the executions, Saâdi assured that none of the numerous bombings after the first meeting with Tillion resulted in civilian casualties.

The most important scenes missing from The Battle of Algiers are the two visits of the ethnologist and deported resister Germaine Tillion to Saâdi, Drif, Ali la Pointe and the female bombmaker Hassiba Ben Bouali in hiding in July and in August 1957. Participants’ accounts of these meetings differ in details, but more importantly in the interpretation of what was going on. [3] Tillion says that Drif spoke little, particularly in the first meeting, which she attributed to the powerlessness of young women in Algerian society. However, Tillion saw Saâdi experiencing a “crisis of conscience” and expressing “evident remorse,” with tears in his eyes, as he spoke of the bombings. When Tillion told the group that they were killers, Saâdi agreed, saying that they had no choice. For “exclusively moral reasons,” Tillion believed, he reached an agreement with her that if the government ended executions of arrested militants, Saâdi’s group would launch no more attacks which targeted civilians. Although Tillion was unable to get the government to stop the executions, Saâdi assured that none of the numerous bombings after the first meeting with Tillion resulted in civilian casualties.

In Saâdi’s 1962 account of the Battle of Algiers, that he drew on for the film, he did not mention the meetings with Tillion, not because they were a secret—she had produced her account for the defense at his trials—, but because this story had no place in the narratives Algerians told of the war of independence at its conclusion. However, when Saâdi published an account of the Battle of Algiers forty years later, he devoted considerable attention to the meetings. He speaks admiringly of Tillion and “of evoking the war and its horrific consequences, thinking that a humanist like her would understand.” Saâdi says he gave Drif the eye when Tillion referred to them as killers to keep her from expressing her anger. He recounts that when “it was time for [Tillion] to regain her serenity,” Ali la Pointe and Drif intervened in a temperate fashion, as agreed upon in advance. Saâdi valued the accord because he saw it as winning for arrested militants some of the rights of prisoners of war and perhaps as a step toward negotiations between the FLN and France.

In Saâdi’s 1962 account of the Battle of Algiers, that he drew on for the film, he did not mention the meetings with Tillion, not because they were a secret—she had produced her account for the defense at his trials—, but because this story had no place in the narratives Algerians told of the war of independence at its conclusion. However, when Saâdi published an account of the Battle of Algiers forty years later, he devoted considerable attention to the meetings. He speaks admiringly of Tillion and “of evoking the war and its horrific consequences, thinking that a humanist like her would understand.” Saâdi says he gave Drif the eye when Tillion referred to them as killers to keep her from expressing her anger. He recounts that when “it was time for [Tillion] to regain her serenity,” Ali la Pointe and Drif intervened in a temperate fashion, as agreed upon in advance. Saâdi valued the accord because he saw it as winning for arrested militants some of the rights of prisoners of war and perhaps as a step toward negotiations between the FLN and France.

Drif’s account in her memoir has a different tone. If she saw herself involved in a negotiation, it was not for the same reasons or in the same way as Saâdi and Tillion. Drif was glad to meet a resister, but was deeply frustrated by Tillion’s refusal to see their fight as akin to the Resistance. When Tillion tells the group they are killers, Drif resented her for making clear, not that they were killers, but that resisters were not necessarily anti-colonialists and that “in the eyes of the French [the Algerians] would never be full humans.” In Drif’s telling, it is only after she had told off Tillion that Saâdi cut her off with a look. In her assessment of the meeting, Tillion emphasizes an age and gender hierarchy—exemplified by the use of “Big Brother” for Saâdi by others in the group, rather than the discipline of an army or a revolutionary organization that Drif saw herself obeying. Drif tells us that Saâdi’s look at her was accompanied by Tillion patting her on the arm and saying that she was still a child. Despite Saâdi’s effort to silence her with his glance, Drif responded that Tillion was “paternalist.” (277) However, through all of this, Drif admires what she calls Saâdi’s “skills as a negociator.” (278) After intervening to help wrap up the deal, Drif gives the accord a different interpretation than Tillion or Saâdi (although Drif attributes it to him as well): without executions and the obligation to respond to them, the group, decimated in terms of both bombs and people, would be able to resupply and to recruit.

What do we learn from these accounts? Drif is telling us what she said or had wanted to say—she speaks more in the account in her memoir than in her own earlier tellings or Tillion’s and Saâdi’s accounts. More importantly, Drif differentiates herself from any expression of the type of moral sensibility that Tillion ascribes to Saâdi. And while Tillion saw herself protecting civilians and Saâdi the captured FLN/ALN fighters, Drif thinks not in terms of individuals, but of protecting the struggle itself. When Drif articulates the proposed arrangement to Tillion, she “spoke slowly, trying to tame the tremor in [her] voice and the sobs that threatened to crush [her] windpipe.” (279) She started crying, but not for the reasons that Tillion attributed to Saâdi, but because she knew they had almost no explosives left.

Drif fascinated the French, who believed that her education should put her on their side. However, it was life underground, not school, that compelled Drif to break a number of taboos. University was her first experience of co-education. Male students of European origin were “asexual beings” to her (37), but to preserve appearances, she communicated with the few Algerian male students by using pied-noir students as intermediaries. However, when she went underground, things changed. She remembers her great discomfort when she found herself eating with three male militants, her first meal with men from outside her family, except those with the bourgeois Lakhdaris. Although the pied-noir press depicted female combatants as Saâdi’s girlfriends in an effort to degrade and shame them, Drif, like Saâdi, makes clear that relationships in the underground were not sexual. However, this did not stop several widely read French novels of the time from having a character inspired by female independence fighters like Drif fall head over heels in love with a French officer, in some cases her torturer. [4]

Although such fantasies lost their raison d’être in a France that came to accept decolonization as the natural course of events, the legacy of the war itself remained. In 2012, Danielle Michel-Chich published a letter to Drif. On September 30, 1956, the five year-old Danielle had gone to the Milk Bar to get an ice cream with her beloved grandmother. She lost a leg and her grandmother to the bomb. The child Danielle is the analogue to the boy licking his ice cream in the Cafétéria that viewers see before the bomb goes off in The Battle of Algiers.

Michel-Chich has a complicated relationship with the perpetrator. She understands Drif’s appeal to Western women of her generation. In the 1970s, Michel-Chich participated in anti-imperialist activities with French men and women who, a decade earlier, had hid FLN militants and smuggled funds to the FLN to Switzerland. She feared they would mistrust her if they knew how she had lost her leg and made up a story about a car accident. Like many feminists of her generation—think of American feminists ululating at the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City in 1968— Michel-Chich was drawn to figures like Zohra Drif: “I admire women who dare, who defy taboos, who assume new roles reserved until then for men.” But she condemned the exercise of violence by women like Drif, a final masculine frontier Michel-Chich refuses to cross. Drif and the bombistes continue to represent the audacity that inspires and troubles activists now as they did then. Michel-Chich finds herself wishing “that bomb was just the crazy, desperate act of a young woman revolted by colonialism, and that [Drif] had left it at that.” [5] Although a victim herself, she recognizes the desire to make an act like that of Drif a kind of performance art, devoid of lost limbs or leading to a post in the post-revolutionary state.

Drif does not rue her actions. She recognizes that this is what readers may expect, but as a soldier at war defending her people against occupiers, she feels no remorse. The closest she comes is changing her use of the term “terrorist.” In La mort de mes frères, a booklet she wrote and published in 1960, Drif identifies her acts as “terrorism,” [6] but in her memoir, references to the actions of her group as “terrorist” are in quotation marks and attributed to the pied-noir press. Those Drif identifies as terrorists are the Ultras who blew up the building on the Rue de Thèbes in August 1956, the event to which the bombings she participated in were a response.

Drif’s memoir ends with her arrest. The collective memory of the war legitimized the post-independence Algerian state, ruled by the FLN. Drif married Rabah Bitat, one of the movement’s founders. In 1999 President Abdelaziz Bouteflika named Drif and Saâdi to the Senate, among the one-third of the senators that the president had the right to appoint. She became vice-president of the body. Drif opposed the government when she believed it was betraying the revolution. In 1980, she fought against a new family code which severely limited women’s rights. Because her own story gave Drif such power, it has been challenged by critics who want to control the narrative of the revolutionary past.

In 2004 the historians Mohammed Harbi and Gilbert Meyner published a book of documents on the FLN that included two letters by Drif to Ben Bouali, in which she purportedly told her that she should surrender to the French and that if she did, they would treat her well. [7] That the letters did not mention Ali la Pointe somehow suggested that she was not interested in saving him. Shortly after Drif’s memoir appeared, Saâdi invited reporters to his house to mark his eighty-sixth birthday. He told them that Drif’s memoir was “full of lies” and that the letters to Ben Bouali were evidence of her treason. He resented Drif referring to him as “El Kho” in her book rather than using his name, seeing in it disrespect rather than evidence of the oppressive respect Tillion had discerned in use of this familial appellation. As the progenitor of The Battle of Algiers, Saâdi has been critical of anything that he thought detracted from his role in the events. However, what has most concerned him was something Drif too addresses in her memoir: the rumors dating back to the war that he and Drif had revealed where Ali la Pointe and Ben Bouali were hiding.

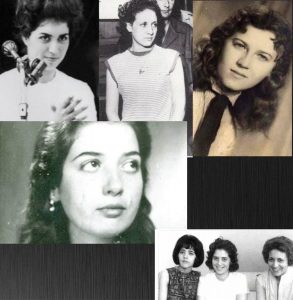

Figure 2 de gauche à droite derrière: Djamila Bouhared, Yacef Saâdi, Hassiba Ben Bouali, Devant : Samia Lakhdari, Petit Omar, Ali la Pointe, une arme à la main, et Zohra Drif. La vraie bataille d’Alger, Jacques Massu, Plon, 1971

Accusers asked why the two of them had surrendered and why they had not been tortured after their arrest. The answer to the first question is that the French said they would blow up the building if they did not surrender. At the time Ali la Pointe and Ben Bouali were hiding across the street, unbeknownst to the French; an explosion would have killed them as well. Deciding to surrender, Saâdi wrote a note in code about their arrest and arranged for it to be telegraphed to Tillion in France. In her memoir (but not in the translation), Drif explains, with supporting testimony, that she found out the details of how the message could have reached Tillion only when she was doing research for this book. [8] Tillion intervened immediately and after extensive efforts was successful in getting Saâdi and Drif the legal protections accorded prisoners in the judicial system. Drif expresses great appreciation to Tillion for her intervention But, she believes, the army, prevented from doing what it wanted to do, sought another way to take advantage of this situation. It realized that dismantlement of the ALN in the Casbah was not enough—it had to undermine the image of the two militants it had captured. The most effective way to do so would be to spread word that they had provided information without being tortured.

Malika El Korso, historian of women in the Algerian Revolution, found the originals of the letters from Drif to Ben Bouali in a folder labelled “Psychological Action” in the French army archives at Vincennes. [9] Harbi and Meynier date the letters to mid-September, that is to say before the arrest of Drif and Saâdi on September 24, 1957. Until the day before, Drif was hiding with Ben Bouali and would have had no need to write her nor any reason to say the French would treat her well. Even if the letters are dated later, Drif did not know where Ben Bouali and Ali la Pointe went after her arrest and so would not have written her. In any case, each letter is in a different handwriting and, Drif added, had “blatant errors in the French that the brilliant second-year law student that I was could not have made.”[10] El Korso believes that the psychological services of the French army composed the letters to use in its campaign to undermine the morale of the FLN. The legend of resistance in Algiers during the war and the reappearance long afterwards of French attempts to destroy it are the context in which Drif wrote her memoir.

Documents released two years later directly targeted Saâdi and by extension Drif. President Bouteflika had a stroke in 2013 and has appeared since then only rarely in public. In January 2014, when Saâdi attacked Drif, he also told the press that it was time for Bouteflika to step down. The following year, Drif joined a group of nineteen political leaders who sought unsuccessfully to discuss with Bouteflika several pieces of legislation he had signed that they felt went against the national interest. In January 2016, neither Saâdi nor Drif were reappointed as senators. Not long afterwards, a detailed organizational chart of the ZAA in 1957 in Saâdi’s handwriting appeared in the Algerian press. [11] But the document was not as damning as it seemed. In her memoir, published a couple of years before, Drif explains clearly how the report on the ZAA, written for the FLN leadership in Tunis and in Saâdi’s hand, was seized by the French, acting on information revealed by a militant being tortured to death, before Saâdi and Drif were arrested.

Revelations and debates in contemporary Algeria resemble those over the individual and collective memory of the Resistance in France a half-century after the events. Iconic resister Lucie Aubrac was made out to be an informer in a text that Jacques Vergès constructed and had Klaus Barbie sign as part of his defense of the war criminal. Vergès used the same argument he had made in his defense of Bouhired: the compromised French republic lacked the authority to judge his client. Other resisters questioned elements in Aubrac’s accounts, without going so far as to support Vergès’ charge. The Vergès/Barbie document led historians in turn to look unsuccessfully for corroboration in the archives. [12] Individual conflicts among historical actors as well as contemporary politics in regimes that look for legitimacy to the Resistance in France and to the struggle for independence in Algeria fed such debates.

The Battle of Algiers is generally presented as historically accurate, although if conflates the three bombers and Ben Bouali in three characters. However, the problem is not this, but that assertions of historical accuracy are made when they present things women did, but not their roles in conceiving, planning and executing these acts. Ali la Pointe has a back-story in the film, but the women combatants do not. Having students who watch The Battle of Algiers read Drif’s memoir opens up their interpretation of the film and the events they see in it. Then and now conflicts over the position and power of women have shaped the ways the stories of women like Drif are told and interpreted. After all, when Saâdi told his superiors that women in his group had set the bombs, they too were surprised.

One of the most engaging elements of Drif’s memoir is that she comes across as a woman in her young twenties, at once like and very different from students her age who read her work as college students. Although Drif is unhesitating in her nationalism and her willingness to die for the cause, she is far from an angel of death. People who engage in acts of terror are invariably presented as unhinged or too tightly hinged, but such characterizations do not fit Drif. Interpretations of what was going on in the meetings with Tillion by those present reveal to students the way that actors in an event— particularly an event that takes place outside of any conventions except those that these actors create for themselves—can view the event as significant, although they may understand that significance very differently. The memoir encourages students to go beyond moral platitudes in discussion of the bombings, situating them in light of Drif’s defense of her actions and Michel-Chich’s condemnation of them. And attention to the efforts of the French army to create doubts about the integrity of FLN/ALN militants gives students an opportunity to think about state creation of evidence to undermine opposition and how such efforts can resurface in new situations.

Drif, Bouhired and Saâdi supported the Algerian youth who took to the streets to oppose Bouteflika’s candidacy for president in March 2019. [13] Drif’s past and her recounting of it retain their power. Reading her memoir develops our understanding of Algerian nationalism, the practice of terrorism, the mobilization of women in Algiers, and the aspirations and agency of sui generis militants like Drif. The Battle of Algiers was Saâdi’s film; Drif was not involved in its production. She said later she would like to make “a really good film” about these events with a director like Costa-Gavros. [14] Her memoir reveals the qualities this film would have.

Drif, Bouhired and Saâdi supported the Algerian youth who took to the streets to oppose Bouteflika’s candidacy for president in March 2019. [13] Drif’s past and her recounting of it retain their power. Reading her memoir develops our understanding of Algerian nationalism, the practice of terrorism, the mobilization of women in Algiers, and the aspirations and agency of sui generis militants like Drif. The Battle of Algiers was Saâdi’s film; Drif was not involved in its production. She said later she would like to make “a really good film” about these events with a director like Costa-Gavros. [14] Her memoir reveals the qualities this film would have.

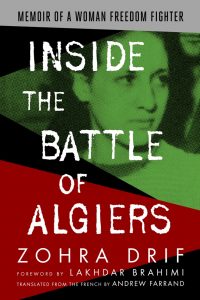

Zohra Drif, Inside the Battle of Algiers. Translated by Andrew Farrand. Charlottesville: Just World Books, 2017.

NOTES

- Danièle Djamila Amrane-Minne, “Women at War: The Representation of Women in The Battle of Algiers,” Interventions 9(3): (2007): 347.

- Neil MacMaster, Burning the Veil. The Algerian War and the ‘emancipation’ of Muslim women, 1954-62 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), pp. 100-102, 322-324.

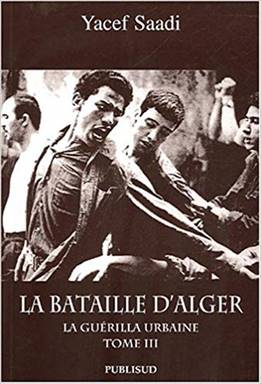

- Quotes in the text are from Germaine Tillion, Les ennemis complémentaires (Paris: Éditions Tirésias, 2005), pp. 60-81, 188-279. Yacef Saâdi, La Bataille d’Alger (Paris: Publisud, 2002), II: 381-424. See also Donald Reid, Germaine Tillion, Lucie Aubrac, and the Politics of Memories of the French Resistance (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), pp. 67-95.

- Donald Reid, “The Worlds of Frantz Fanon’s ‘L’Algérie se dévoile’,” French Studies 61:4 (October 2007): 460-475.

- Danielle Michel-Chich, Lettre à Zohra D. (Paris: Flammarion, 2012), pp. 67, 100-101.

- Zohra Drif, La mort de mes frères (Paris: François Maspero, 1960), pp. 8, 13.

- Mohammed Harbi and Gilbert Meynier, Le FLN. Documents et Histoire 1954-1962 (Paris: Fayard, 2004), pp. 140-41.

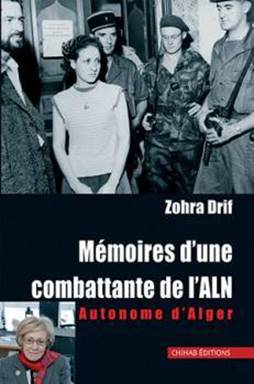

- Zohra Drif, Mémoires d’une combattante de l’ALN. Zone Autonome d’Alger (Bab El Oued: Chihab Éditions, 2013), pp. 562-575.

- Malika El Korso, “L’historienne Malika El Korso recadre Yacef Saâdi,” February 3, 2014. https://www.algerie360.com/lhistorienne-malika-el-korso-recadre-yacef-saadi/

- “Zohra Drif: le 8 Mars, son combat et l’ecriture de l’histoire, ‘Je n’ai jamais cru aux droits offerts sur un plateau d’argent’,” March 8, 2014. https://www.algerie360.com/zohra-drif-le-8-marsson-combats-et-lecriture-de-lhistoire-%C2%ABje-n%E2%80%99ai-jamais-cru-aux-droits-offerts-sur-un-plateau-d%E2%80%99argent%C2%BB/

- “Algérie, 2016: révélations sur le rôle de Yacef Saâdi, héros de la ‘bataille d’Alger’ de 1957,” April 12, 2016. https://algeria-watch.org/?p=45430

- Donald Reid, Germaine Tillion, pp. 127-175.

- For Drif’s support of opponents to the Bouteflika candidacy, see Hacen Ouali, “Algérie et le camp «Boutef» flippa,” Libération, March 7, 2019. https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2019/03/07/algerie-et-le-camp-boutef-flippa_1713690

- Danièle Djamila Amrane-Minne, Des Femmes dans la guerre d’Algérie (Paris: Karthala, 1994), p. 142. Such a film, whether done when Drif made this comment, around 1980, at the time the family code was being debated, or now, would certainly elicit efforts to control its content from a regime that presents itself as the fulfillment of the revolution. This may be one reason that Drif thought of a foreign director. In 2017, when an Algerian director proposed to do a film on Djamila Bouhired, Bouhired got the project cancelled: “In a context of uninhibited falsification that attempts to carve out a story tailored to usurpers and forgers, this operation aims, once again, to exploit the War of National Liberation for the purpose of legitimizing power.” Abdou Semmar, “Film sur la guerre de Libération: Djamila Bouhired dit non à la récupération politique du pouvoir,” Algérie Part, June 21, 2017. https://algeriepart.com/