Roxanne Panchasi

Simon Fraser University

Gerboise bleue

et gerboise verte

née de la bleue,

gerboise violette

née de la verte,

gerboise blanche

née de la violette,

gerboise jaune

née de la blanche,

gerboise rouge

née de la…-Hawad, Sahara: Visions atomiques [1]

“[C]e qui est sûr c’est que cuite ou crue, vivante ou morte, la gerboise n’est pas bleue.”

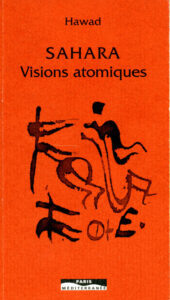

Sahara: Visions atomiques, a powerful collection by the Tuareg poet Hawad, first appeared in French translation in 2003. Composed originally in the Tamazight dialect using the Tifinagh script, the poems are at once easy and difficult to read. In short, dreamlike lines that tumble breathlessly down the volume’s pages, Hawad writes from/for a people and spaces traumatized by a long history of French imperial violence. From 1960 to 1966, after more than a century of colonial occupation in Algeria, the French military exploded multiple nuclear bombs in the region of the central Sahara inhabited by the nomadic Tuareg: four atmospheric tests at Reggane, then another 13 underground, southeast at In Ekker. After this period of nuclear experimentation that began during the Algerian War and continued on the other side of Algeria’s independence in 1962, France relocated its nuclear testing program to the Pacific. The environmental, health, and psychological effects of the detonations in the Sahara have continued to radiate, quite literally in some ways, for decades since.[3]

Hawad’s “atomic visions” are lyrical, emotive texts that bear witness to the harm wrought by militarized science and spectacle à la française. Reinterpretations of Tifinagh characters, the author’s accompanying calligraphic illustrations support the poems throughout, their stark, monadic forms suggesting a community in geographic and historical movement and pain. Referencing the dead and diseased bodies made sick from exposure to initial blasts and the still-contaminated land, air, water, flora, and fauna of the desert and its oases, Hawad’s poems respond to a history of colonial invasion, occupation, catastrophe, and ruin.[4]

Mapping the terrain of a literary and archival imaginary that remembers, confesses, and testifies, this essay considers three contemporary novels published in French that revisit the difficult history and legacies of nuclear testing in the Sahara: Victor Malo Selva’s Reggane mon amour (2011), Christophe Bataille’s L’Expérience (2015), and Djamel Mati’s Sentiments irradiés (2018).[5] With Hawad’s poetry, these texts inhabit a category of writing that confronts past and present in modes at once creative and documentary.[6] Instances of a growing field of Franco-Algerian nuclear-imperial fiction, the novels share formal, thematic, and affective elements that make their contemplation as a group meaningful and worthwhile.

That these titles focused on French nuclear testing in Algeria during the 1960s were all published after 2010 is not incidental. That year marked the 50th anniversaries of France’s first three atomic tests in 1960: Gerboise Bleue on February 13th, Gerboise Blanche on April 1st, and Gerboise Rouge on December 27th.[7] It was also the year the French government passed the Loi Morin, legislation outlining an indemnity process for victims of France’s nuclear tests in the Sahara and the Pacific.[8] Military files remain largely inaccessible due to the classification of nuclear weapons as matters of national defense. At the same time, reports and debates leading up to and since the passage of the Loi Morin; pressure from French veterans’ groups and from the Algerian state; the revelation of archival evidence (some of it leaked); the work of journalists and documentary filmmakers; and increased public interest and awareness regarding the colonial past as a whole, have played important roles in opening up space for the acknowledgment of France’s nuclear tests in empire, their long-term human and environmental costs.[9] The past two decades have also been a period of expanding scholarly investigation of the history of French colonialism, and the Algerian context in particular. Finally, despite a persistent tendency to segregate the history of French nuclear testing from the history of the Algerian War per se, the proliferation of work on the wartime period during which the tests began has created possibilities for their illumination and a fuller integration of French nuclear imperialism into analyses of the era of decolonization.[10]

Set at different historical moments, moving back and forth between different pasts and presents, the novels by Selva, Bataille, and Mati share some common features as a group, but they also diverge in important ways, including their use of narrative voice, approach to storytelling, and presentation of the history of France’s nuclear weapons exploits in Algeria. Published in 2011, Selva’s Reggane mon amour is the guilt-ridden fictional memoir of a dying French veteran at the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century. During his final days, the novel’s “hero,” Louis-René, a man who served in the military during the Algerian War, reflects on his own complicity in French colonial violence and atrocity. Following in the footsteps of a father who fought bravely and died in defense of France during the Second World War, Louis-René participates enthusiastically (at first) in his nation’s efforts to keep Algeria “French” from 1954 to 1962. Dealing with strife within the military, racism, and torture, the novel tracks Louis-René’s gradual disillusionment with aspects of his own, and la patrie’s, military mission. He accepts reassignment from the thick of the conflict to the nuclear test site at Reggane in 1958, a little over a year before the detonation of Gerboise Bleue. In the Sahara, Louis-René witnesses this first and then a series of subsequent atmospheric and underground tests. In addition to causing enormous immediate destruction, even death, the bombs he helps to explode/test give off radiation that severely affects his own health in the long term.

Reggane mon amour is a heavy book, in the historical events, themes, and emotions it engages, and as a reading experience. Looking back from “the present,” Louis-René addresses his own wife and a number of other possible readers. More than a straightforward memoir, the novel is interrupted by letters and reports, some written by supporting characters/witnesses who offer different perspectives and corroborate Louis-René’s story. The novel also includes a hand-drawn illustration of the test site at Reggane, a “Non-Exhaustive List of Radiation-Induced Diseases,” and a “Glossary” of key acronyms—the FLN, MNA, OAS, and POUM (the status of this last as either contained by, or separate from, the memoir itself is somewhat ambiguous). Moments in the novel read like an exposé, even a textbook. Educating the reader about the history of colonialism in Algeria, the damage done by France’s nuclear tests, and the continuing insufficiency of forms of acknowledgment and restitution up to the present, Louis-René’s “dossier” even includes a discussion of the 2010 Loi Morin passed just before the novel’s publication. The effect is intensely didactic. Demanding justice for victims of the actions and inaction of the French state and military, the novel makes its case in ways that blur the boundaries between its main character/author and Selva himself.

Christophe Bataille’s L’Expérience is another fictional veteran’s memoir. Writing decades later to unburden himself of his story, the narrator shares his experience of Gerboise Verte, the April 1961 atmospheric bomb test at Reggane. An engineer by training, he arrives in the Sahara under curious circumstances on the eve of the test. Like Selva’s Louis-René, Bataille’s narrator also feels intense guilt. But L’Expérience is focused more on its central character’s victimization by a nation and military that have treated him as dispensable, a cobaye (guinea pig) not unlike the other live animals placed (along with various military equipment) in proximity to ground zero during the tests. Like the Algerian workers on-site and civilian inhabitants of the region who were neither sufficiently informed about the detonations, nor warned of the dangers they posed, French soldiers were also subjected to the blasts and their aftermaths. In some cases, the novel contends, the military willingly placed soldiers in harm’s way with the intention of collecting data about the tests’ effects on human beings.

Bataille’s fiction jumps abruptly between past and present throughout, its evocative snapshots disorienting the reader and conjuring the fear, pain, and shock of traumatic events and their memorial repetition. While the young soldier survives l’expérience, his subsequent life is deeply affected by his experience of this organized instance of nuclear devastation enshrouded in secrecy and lies.[11] “They lied to me,” scribbles the narrator in a notebook he has devoted to his recollections. “They lied to us. We were pushed, of course. Forced. They lied to the workers too. To those poor inhabitants of the desert.”[12] This ailing witness’s testimony is individual, personal, but also collective and political in its content and form. Meeting the destructive and deceitful science of France’s nuclear imperialism with an obsessive disclosure that revisits and releases years of suffering, L’Expérience confronts a French state and military that for too long refused to acknowledge their atrocious acts in the desert, even “now” failing to offer their victims sufficient transparency, recognition, and restitution.

Djamel Mati’s Sentiments irradiés appeared in 2018. Written in French by a well-known Algerian author and published by an Algerian press, the novel centers the Algerian experience of French nuclear imperialism in the Sahara.[13] While both Selva and Bataille are attentive to the suffering of Algerian workers, FLN fighters, and civilians during and after the war and France’s bomb experiments, Mati’s novel prioritizes the impact of this period on the people most harmed by its violence and injustices. Kamel, the novel’s protagonist, is a brilliant student who studies law before becoming involved with the FLN in Algiers after 1954. Forced to flee to the desert to avoid capture by the French authorities, Kamel eventually finds himself, along with his pregnant wife, near the test site at Reggane just before the detonation of Gerboise Bleue on February 13th, 1960. The tragedy and wreckage of this day will mark him for the rest of his life.

None of this is laid out clearly from the beginning of the novel which, like the other two, is set up as a return from a present many years later, in this case, 1986. Two and a half decades after Gerboise Bleue, Kamel travels to France during a wave of terrorist bombings to give a presentation on the lasting impact of the nuclear tests in the Sahara at Greenpeace’s national headquarters.[14] In Paris, he meets Zoé, a young French woman working with the environmental organization who (we later learn) was born on February 13th, 1960. Eventually, Zoé introduces Kamel to her father, Paul, a doctor who served in the military during the Algerian War.

Through a series of letters Kamel writes from Paris to his friend Kadda, still in Algeria, the reader learns the details of Kamel’s life up to this point, including the loss of Kella, his wife, and their newborn child, at Reggane, after the detonation of Gerboise Bleue. Towards the end of the novel, Kamel learns a horrifying secret: Paul, Zoé’s father, was stationed at Reggane on February 13, 1960. He had had the opportunity to help Kamel and his family but refused. Paul invites Kamel’s vengeance and his own release from years of guilt. He too has been haunted all this time. Torn between past and present, Kamel struggles with his rage, his grief, and his romantic feelings for Zoe. At the end of the narrative, he returns to Algeria. Questions remain about the novel’s characters and their futures. Much in this fiction, as in the historical and contemporary landscapes it references, is left unsettled, a wound that can never completely heal.

Approaching “nuclear fiction” in French as a broad category, the title that immediately comes to mind is Hiroshima mon amour, the 1959 film directed by Alain Renais, with a screenplay by Marguerite Duras. There is much more to say than I have room for here about the memory of nuclear atrocity that pervades the film’s exchanges between a French woman (“Elle,” played by Emmanuelle Riva) and a Japanese man (“Lui,” played by Eiji Okada). The two become romantically entangled in Hiroshima years after the 1945 U.S. atomic bombing of the city. Sharing the stories of their past love affairs in conversations that return again and again to the war’s losses and destruction, the two characters/actors first appeared on French screens in 1959, as the nation/empire’s military engaged in the final stages of preparation for its first atomic test in the Sahara. A 1960 Folio paperback edition of the screenplay (published by Gallimard) that followed the film’s release featured a provocative illustration by the artist Frédéric Blaimont: a pair of deep red lips, disconnected uncannily from any individual body, wrapped from the book’s spine across its front cover. Blaimont overlaid this vibrant image with a drawing of an atomic mushroom cloud rising from the lips’ meeting point to their upper edge known as “Cupid’s bow.” The illustration’s collage of sex, love, and destruction is beautiful, and also horrible.[15]

A brilliant artifact of the French New Wave and a meditation on memory and nuclear destruction, Hiroshima mon amour did not acknowledge France’s own impending atomic plans in Algeria. “The bomb” was not yet “French.” In retrospect, the timing of the film’s appearance in relationship to the inaugural of French nuclear tests in the Sahara eerily reinforced a French insistence that detonating weapons of mass destruction in the desert as part of a program of military and scientific experimentation could be acts of “peacemaking” and “deterrence,” harmless incidents that would incur no victims.

Hiroshima mon amour may not explicitly address France’s nuclear imperialism in Algeria, but the nuclear fictions in French that interest me here do reach for and recall the images and emotions Duras and Resnais brought to page and screen just before the first French atomic test. Selva’s Reggane mon amour does so most obviously with its title, but also in its inclusion of love letters and more than one romance woven into its narrative. Returning from his traumatic experience in the Sahara, Bataille’s main character falls in love with a woman he meets in a darkened cinema. One night, after he tells her everything he has witnessed, her eyes fill with tears. Saturated with trauma, Mati’s novel is also, at some level, a (double) romance riven by the memory of love and loss. Kamel’s love for Kella haunts him, and this Algerian man’s relationship with Zoé, a French woman, brings him back to the scene of his original devastation in the Sahara.

Beyond these echoes of a 1959 film preoccupied with physical and emotional love and destruction, the three novels I have considered here share other common features. In all three, the damage and suffering caused by France’s nuclear tests in the Sahara are worked over and through. Human bodies are burned, scarred, and destroyed, their flesh and skin holding and revealing radiation’s traces for decades after the blasts. In these narratives, the desert, too, is a body in ruins, a setting, a character, and a space of memory. Fascinated with this traumatic period in the French and Algerian pasts, the authors of these novels all speak to, and on behalf of, different categories of victims and perpetrators. Looking backward from a shifting present, their texts blur the lines between then and now, between historical positionalities, between life and death. An archival sensibility runs through these meditations on violence, loss, and regret. Referencing the work of scholars (Bruno Barrillot, Christine Chanton, and Benjamin Stora among them) the three texts present and interrogate a range of sources and evidence: first-hand accounts, reports, letters, photos, maps, and illustrations. Writing is everywhere in these novels about how and why we refuse or choose to remember, cannot and should not forget.

Christophe Bataille, L’Expérience (Paris: Grasset, 2015)

Djamel Mati, Sentiments irradiés (Alger: Éditions Chihab, 2018)

Victor Malo Selva, Reggane mon amour (Brussels: Éditions Aden, 2011)

NOTES

- Hawad, Sahara: Visions atomiques (Paris: Éditions Paris-Méditerranée, 2003).

- Christophe Bataille, L’Expérience (Paris: Éditions Grasset, 2015).

- For a recent study of the lingering impact of France’s tests in Algeria, see Jean-Marie Collin and Patrice Bouveret’s Radioactivity Under the Sand (Berlin: Heinrich Boll Foundation, 2020). On the history of French nuclear testing in general and the choice of the Sahara as a test site in particular, see Yves le Baut, ed., Les essais nucléaires français (1996); Dominique Mongin, La bombe atomique française 1945–1958 (1997); and Jean-Marc Regnault, “France’s Search for Nuclear Test Sites, 1957–1963,” Journal of Military History, 67.4 (2003): 1228-1248. On veterans and victims, see Bruno Barillot, Les Irradiés de la République:, Les victimes des essais nucléaires français prennent la parole (Brussels: Éditions Complexe, 2003); Christin Chanton, Les Vétérans des essais nucléaires français au Sahara, 1960-1966 (Paris: Éditions L’Harmattan, 2006); and Jean-Philippe Desbordes, Les Cobayes de l’apocalypse nucléaire, Contre-enquête inédite sur les victims des essais nucléaires français (Paris: Express Roularta Éditions, 2011.

- “Ruin” here refers to a range of material and less tangible toxicities. I am indebted to Ann Laura Stoler’s Imperial Debris: Ruins and Ruination (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013) for its critical and expansive development of the term.

- See Bataille; Victor Malo Selva, Reggane mon amour (Brussels: Éditions Aden, 2011); and Djamel Mati, Sentiments irradiés (Alger: Éditions Chihab, 2018). For a discussion of “nuclear imperialism” as a term originally used by Pan-African and pacifist activists who opposed French testing in the Sahara in the 1950s and 1960s, see Jean Allman, “Nuclear Imperialism and the Pan-African Struggle for Freedom, 1959-1962,” in Souls 10.2 (2008): 83-102.

- There are other examples I do not discuss in this essay. One of these is Gérald Tenenbaum’s L’Affinité des traces (Paris: Éditions Héloise d’Ormesson, 2012), the story of Édith, a French Jewish woman whose parents perished in the Holocaust. In 1962, after enlisting in the French military as a secretary, Édith is stationed at a military base and nuclear test site at In Ekker in the Sahara, at the end of the Algerian War. I have chosen to focus on key examples of Francophone works that “return” to the period of France’s initial atomic tests in Algeria, those that coincided with the War of Independence. Tenenbaum’s novel certainly shares some of their concerns, and there are other texts worthy of analysis along the lines I suggest that I do not have the space to explore here. I have also not included works (apart from the Hawad) published in languages other than French.

- Gerboise verte, the fourth atmospheric test conducted at Reggane, took place in April 1961.

- For the text of the Loi Morin and subsequent revisions, see the French government webpage: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000021625586

- For more on veteran activism, see the website for L’Association des vétérans des essais nucléaires au Sahara et en Polynésie et leurs familles or AVEN (https://aven.org/). The French daily, Le Parisien has in recent years broken a few stories related to the tests in the Sahara. See, for example, Sébastien Ramnoux. “Le document sur la bombe A en Algérie,” February 14, 2014. Key documentary on the tests include: Blowing Up Paradise, dir. Ben Lewis (2005); Gerboise Bleue, dir. Djamel Ouahab (2009); L’Algérie; Vents de Sable, dir. Larbi Benchiha (2008); De Gaulle et la bombe, dir. Larbi Benchiha (2010); Le Secrets des irradiés, dir. Sébastien Tézé (2010; and At(h)ome, dir. Elisabeth Leuvrey (2013).

- See my article, ‘“No Hiroshima in Africa”: The Algerian War and the Question of French Nuclear Testing in the Sahara” in History of the Present 9.1 (Spring 2019): 84-112.

- The slippage between the French expérience or “experiment” and the English “experience” is meaningful here.

- Bataille, 51.

- Mati is the author of several other novels, including Yoko et les gens du barzakh (Algiers: Éditions Chihab, 2016) for which he was awarded the Grand Prix Assia Djebar in 2016.

- While aspects of the novel are fictional, the series of bombings in 1985 and 1986 was very real. See Dider Bigo, “Les attentats de 1986 en France: un cas de violence transnationale et ses implications” in Culture & Conflits (Winter 1991): 1-16.

- Marguerite Duras, Hiroshima mon amour (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1960). For an analysis of gender, sexuality, race, and violence in the film, see Sandrine Sanos, ‘“My Body was Aflame with His Memory”: War, Gender, and Colonial Ghosts in Hiroshima mon amour (1959)” in Gender and History, 28.3 (November 2016): 728-753.