Abigail E. Lewis

University of Wisconsin-Madison

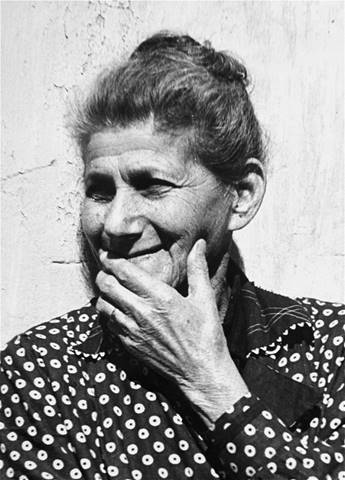

Julia Pirotte, self-portrait 1943. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Julia Pirotte.

Photographs hang in a tenuous balance between factual objectivity—as a kind of historical evidence in their own right—and human perspective. In fact, as Susan Sontag has told us in Regarding the Pain of Others, “Photographs had the advantage of two contradictory features. Their credentials of objectivity were inbuilt. Yet they always had, necessarily, a point of view. They were a record of the real…And they bore witness to the real—since a person had been there to taken them.” [1] Thinking of images as a kind of visual record open to analysis, rather than mere illustrative devices gets students to think not just about what they see, but about who might have taken the photograph and why. How do images function in their own historical moment? What role do they play in Holocaust memorialization and collective memory?

In the case of France, most photographs of the war years and the Shoah are tinted with the mechanics of the Occupation in big and small ways. Outdoor photography was banned in occupied France beginning in September 1940 and by 1942 in Vichy. This meant that most photographs that depict the Nazi occupation or the persecution of Jews within France’s borders were most often taken not necessarily with permission, but at least by a photographer deemed fit to work by the German authorities or the Vichy Regime. While images of occupied France are abundant and serve to depict what daily life under occupation may have looked like, their material histories can raise troubling questions about the political and cultural circumstances of both their creation and their subsequent display. The complexities of these questions, which get at the on-the-ground experiences of Nazi occupation, is precisely what makes photographs interesting as teaching sources.

In reflecting on the spectrum of everyday stories that photographs can tell regarding the occupation and the Shoah in France, this review will focus closely on the story and photographs of Polish-Jewish photographer Julia Pirotte, who was active in Marseille between 1940 and 1945. The most complete collection of Pirotte’s images from occupied Marseille to postwar Poland are published with translated text and biographical information in Julia Pirotte: Faces and Hands by the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. [2] I will highlight Pirotte’s efforts to visualize the everydayness of the Occupation, collaboration, and resistance in Marseille and the ways that her photographs can engage students with this history. In particular, I am interested in drawing out Pirotte’s story as establishing nuances in daily life and decision-making for artists under occupation. Her story and her photo-stories continue the work of destabilizing histories of collaboration and resistance. Pirotte had a unique set of options as a photojournalist and her clandestine activity was facilitated by her willingness to work with the authorized, official French press and state authorities. For this reason, I have included a set of—potentially—propagandistic images that she produced at the Hôtel Bompard internment camp in July 1942. Her images of the camp provide important documentation on the implementation of French antisemitic policy and the reality of deportation. The images also raise questions about Pirotte’s own approach from behind the camera.

Speaking more than forty years after the end of the war, Pirotte recounted her motivations for photographing both officially and clandestinely in occupied Marseille: “I wanted to leave a little bit of history—what is war, what is occupation, what is Nazism. And my camera helped me in this.”[3] Pirotte created hundreds of photographs of everyday life, resistance, and persecution in occupied Marseille. Her photos offer a visual documentary record that shifts our focus away from political ceremonies and leading figures of the Vichy Regime towards everyday scenes and the public. Pirotte’s images, housed now at various institutions dedicated to the study of the Holocaust and World War II, include celebrities, Jewish refugees, French peasants, the workers, wives, mothers, children, aid workers, and resistors. More than just a talented documentarist, Pirotte was also an artist, a journalist, a committed Communist activist, and an immigrant herself. The careful framing of her photographs reflects back on her own identity and her experiences with persecution and displacement throughout her life. Pirotte’s own personal story is imprinted upon these pictures; her images are the result of her artistic and human response to state and local violence, persecution, and ideologies that she encountered throughout her entire life.

Pirotte was born in 1908 in a Polish shtetl and knew political persecution and antisemitic violence from an early age.[4] In her 1986 oral testimony for the Fortunoff Video Archive, she remembered hearing rumors of threats of pogroms in surrounding villages. At only eighteen years old, Pirotte spent four years in prison for her involvement in the Polish Communist party. In 1934, fearing another arrest, Pirotte left Poland for France where her younger sister Mindla was living. Pirotte fell ill along the way and settled in Brussels, where she worked as a journalist, and published impassioned social and political critiques. Pirotte’s writing and activism caught the attention of Suzanne Spaak—a woman now famous for rescuing Jewish children from France. Spaak was executed by the Nazis in August 1944. Spaak encouraged Pirotte to go to photojournalism school and gifted her with an expensive Leica Elmar III camera.[5] This camera became Pirotte’s prized possession, which she used throughout the rest of her career. From the earliest days of the war, Pirotte understood her task as social and historical. Pirotte wielded her camera—her weapon—to record social inequities and to document the heroic actions of her comrades in the resistance, many of whom, including her sister Mindla Diament and Spaak, would not live to tell their own stories.

In 1940 Pirotte headed to France, armed with what she described as her “instrument of struggle”—her camera—to aid in the fight against Nazism. Pirotte settled in Marseille, where she worked in an airplane factory until the fall of France. Once France signed the June 1940 armistice, Pirotte looked for new ways to make a living and to continue fighting Nazism. To make ends meet, Pirotte began to take and sell photographs on a private beach in Marseille. Pirotte lived near a photography shop by the Old Port, where she had access to film. At night, Pirotte developed the film at the apartment of a friend and in her own kitchen sink. Pirotte’s networks and the relatively freer atmosphere for photography in the “free zone” initially allowed her to make money selling photos on the beach. However, photographic materials and the ability to photograph publicly without authorization would become much more difficult as the Occupation went on. Pirotte was eventually forced to abandon her beach photography once the Gestapo began looking for her—the “woman with the camera.”[6] This illustrates one way that a Jewish photographer found ways to make money, the material difficulties of selling beach photos, and the risk that photography carried.

Pirotte’s clandestine and resistance photographic work was facilitated by her employment by an official French newspaper, Dimanche Illustré (hereafter DI).[7] After the Germans invasion of Marseille in November 1942, Pirotte accepted a position as a photojournalist with DI. When she accepted the job, Pirotte believed that the editor at DI knew that she was Jewish and in the Resistance. She remembered that the editor “winked his eye.”[8] As a photographer for DI she photographed celebrities that visited Marseille, including Edith Piaf. Throughout her time in Marseille, Pirotte served in both the Communist and Jewish resistance. She carried weapons and clandestine papers for the Francs-tireurs et main d’oeuvre immigrée (FTP-MOI) and used her photographic skills to produce false ID cards. With her photojournalist credentials in hand, she was able to serve as a courier between Marseille, Arles, and Nimes because she was afforded more mobility throughout occupied France. Pirotte’s position at DI provided a cover during her trips and saved her from suspicion. Her press-pass saved her life on a trip to deliver clandestine papers. She arrived late in Arles, past curfew, with a suitcase filled with underground newspapers. She and others on the train were to be held overnight in the station. Pirotte showed the German soldiers her press pass and said she was in town making a report for DI. The soldiers let her go and did not search her suitcase.

Julia Pirotte, August 29, 1944, “A group of Jewish women members of the emigré sections of the FTPF.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Julia Pirotte.

Pirotte’s permission to photograph for DI and her access to film materials also allowed her to produce her own photographic documentation of Marseille, especially the activities of the resistance and daily life. Pirotte was a new photojournalist in 1939. It was in this context of war, occupation, and resistance that Pirotte began to experiment with her aesthetic approach. Pirotte later described her images as “made spontaneously, born out of an inner need.”[9]

As a human being and a photographer, I couldn’t ignore the important events I was witnessing. Could I just pass by without capturing the concerned faces of the miners’ wives in Gardanne? The sad distrustful faces of the kids I met in the narrow, winding streets around the Old Port? The weary gazes of women queuing up for hours in front of a butcher shop or bakery? Could I not have photographed scenes that formed an integral totality of wartime life?

Responding to this inner need to document what she could of suffering and of resistance, her photographs attest to the subjective and human experiences of life under occupation in Marseille.

Allowing us to see occupation through Pirotte’s own eyes, the photographs are not simply a record of events. Pirotte’s own experiences and relationships within Marseille underwrite the aesthetic framing of the shots. Pirotte’s photographs collectively show what occupation looked like on the ground level for a range of everyday individuals. Included amongst the subjects she depicts are women and children living in the streets, workers’ wives, mothers caring for their children, and other artists. As a journalist, artist, and a “human being,” Pirotte was compelled to photograph the scenes that she most identified with personally and politically, the individuals that she found most representative of the “other half” of the Occupation. These images differ considerably from the Vichy focus of other photographers who concentrated on political leaders visiting Marseille and the city’s political life. Her images can give students a lens into living conditions, emotional experiences, and artistic endeavor during the Occupation that contrast with the more famous Paris-centered photographs generally utilized in discussing this history. Pirotte visualizes Marseille’s story from the inside; they are snapshots of a city which had become a new home for herself and for others who had found refuge there. Pirotte acted more as artist and documentarian of her city, her compatriots, and her neighbors than as eyewitness. Through artistic representation, she did what she could to preserve the memory of their struggles and resistance.

Furthermore, Pirotte’s photographs attest to the choices she had to make: choices that were not without a moral ambiguity. Towards the end of her Fortunoff interview, Pirotte discussed a set of photographs that she took in July 1942 at the Hôtel Bompard internment camp.[10] It housed women and children who had applied to immigrate, usually to the United States. Pirotte was stopped on the street by a camp commandant, whom she identified as a Frenchman, and was told to show up the next day to photograph a banquet that she was told was organized by the Joint Distribution Committee. Pirotte recounted: “I went, I photographed the children laughing, dancing, the mothers happy, all normal. I developed the photos and gave them to the camp.” [11] Pirotte found out that several days after her visit the women and children at the camp had been deported, most to Auschwitz. The Bompard photos raise complex moral questions regarding photography and Jewish internment camps in France. The photographs, a few of which are included here, display women and children happily playing. Pirotte documented the banquet that was perhaps staged for her benefit. In her Fortunoff interview Pirotte herself wrestles with the problem of participating in the camp’s events in even the most tangential way.[12] Regardless, Pirotte’s photographs are deeply humanizing and were likely the last visual traces of many of these women and children. The haunting weight of the Hotel Bompard photos, as a last look at the final days of the camp, only becomes clear in retrospect when one knows the fate of those interned. Despite Pirotte’s Jewish roots, the Bompard photos are some of the few images that depict the deportations in France.

Julia Pirotte, July/August 1942, “Jewish refugee children interned at Hotel Bompard.” United States Holocaust Memorial Muesum, courtesy of Julia Pirotte

Julia Pirotte, July/August 1942. “Portrait of an elderly Jewish refugee woman at the Hotel Bompard.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Julia Pirotte.

At the end of the war, Pirotte returned to Poland with a sack on her shoulders, her camera, and 500 photographs. In Poland, she again wielded her camera to photograph the desolation and suffering that she found in the wake of the Holocaust and the physical, and social, destruction of Poland. In 1946, she received word of a pogrom in Kielce and was sent by her newspaper to take some photographs. Pirotte was the only photographer on the scene and produced 118 images of this episode of postwar antisemitic violence. Today, these images exist only in grainy fragments because they were destroyed by the political police. She was able to recreate a few of the images based on test negatives. She had once again become a photographer documenting persecution, but her role had shifted to eyewitness—the only witness with a camera— to mass violence against Polish Jews newly returned home as survivors of the camps. She was then aware of photography’s importance as historical evidence.

These Kielce images and her aesthetic approach differ drastically from those snapshots of Marseille. The Kielce photos were destroyed because they served as evidence. The images provided historical proof of postwar antisemitic violence. The few existing images are the only visual evidence of the pogrom. As a Jew also returning to Poland, Pirotte photographed the pogrom with an intimate sense of the danger of her own homecoming. She had to collect as many photos as possible regardless of aesthetic quality and also hide them. After they nonetheless disappeared, Pirotte did what she could to recreate them.

Unlike her Marseille photos, they directly depict bodily damage against specifically Jewish residents of Kielce. The images are emotional in their direct depiction of violence, rather than her aesthetic choices. In some images, it is unclear if the person in the photo is dead or alive. Their lives hang in-between. As a Jew and former refugee, Pirotte realized the risk in going to Kielce and used a bodyguard. Her own life was in danger by being there. Despite the damage the images have incurred, which adds to their story, one can palpably feel the shock she experienced while she was photographing and how she identified with the violence. In taking these photographs, and later restoring them, Pirotte took on the role of eyewitness and documentarian, recording the continued violence against Polish Jews that occurred after the Holocaust.

Julia Pirotte, July 6, 1946. Kielce, Poland. “A Jewish woman who was injured during the Kielce pogrom lies in a hospital bed.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Julia Pirotte.

Julia Pirotte, July 6, 1946. Kielce, Poland. “A victim of the Kielce pogrom recuperates in a local hospital.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Julia Pirotte.

Pirotte’s wartime and postwar photographs demonstrate the different kinds of memory work fulfilled by photographs. At the end of her oral testimony, Pirotte states that we must not glorify her; we only know her name after all thanks to her camera. Yet her story and her images and their postwar afterlives emerged within specific European collective memories of warfare, occupation, and antisemitism beginning in the late 1980s.[13] Pirotte admits that she kept her photographs of Marseille in a drawer for more than 30 years because she did not believe that Poles, who had suffered their own tragedies and had their own uprisings, would care to see her images of occupation in Marseille. Her perspective shifted when she visited Paris in 1979 for the first time since 1945. She discovered her Marseille images in a film about the French Resistance. Once back in Poland she made copies of her Marseille photos, adding her stamp, and began to send them to institutions and libraries across France. Her photos of the Liberation in Marseille helped to sustain collective memories of the people’s uprising. Rather than as witness to occupation in Marseille or survivor of the Shoah, the presentation of her photos in Western Europe has emphasized her role in documenting the Resistance.

Fulfilling her aim to preserve bit of history, Pirotte’s photographs powerfully display to students what the war, the Occupation, and the Shoah were like in Marseille. However, her Kielce photos serve as a different kind of visual evidence of violent persecution. Pirotte realized that her task was not just to offer historical snapshots, but to document an event for the historical record. The Kielce photos reveal the reality of postwar antisemitic violence in Poland and the horror she witnessed as a Polish-Jew and journalist.

NOTES

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2013), 26.

- Julia Pirotte: Faces and Hands (Warsaw, Poland: Jewish Historical Institute, 2012).

- Interview with Julia P., Fortunoff Video Archive, Yale University, October 25, 1986. Translation from Yiddish from the partial transcript. Accession number HVT-774. You can also find clip of the testimony with full translation at https://perspectives.ushmm.org/item/oral-history-with-julia-pirotte/collection/artists-and-visual-culture-in-wartime-europe#. Unless noted, all quotes come from the Fortunoff testimony.

- I have seen her birthdate listed as both 1907 and 1908. Here I am using the birth date given in the Fortunoff interview.

- Pirotte discusses the gift in her Fortunoff interview. The episode is also recounted from Spaak’s perspective in Anne Nelson, Suzanne’s Children: A Daring Rescue in Nazi Paris (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017), 4.

- Interview with Julia P., Fortunoff Video Archive, Yale University, October 25, 1986. HVT-774. Segment 8.

- It is not exactly clear when exactly she starts to work for the paper. She mentions that Marseille was no longer free and she began to work for DI, suggesting that she accepted the position sometime around the invasion of the south of France in 1942.

- Interview with Julia P., Fortunoff Video Archive, Yale University, October 25, 1986. Translation from Yiddish from the partial transcript. Accession number HVT-774. Segment 9.

- Quoted by Krystyna Dabrowska, “Faces and Hands,” in Julia Pirotte: Faces and Hands (Warsaw, Poland: Jewish Historical Institute, 2012), 9.

- Donna Ryan identified the photos as being taken in August 1942, but Pirotte stated that they were taken in July 1942. The residents of the Hôtel Bompard were sent to Les Milles and then deported to Auschwitz in August 1942. Donna Ryan, The Holocaust and the Jews of Marseille: The Enforcement of Anti-Semitic Policies in Vichy France (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 94.

- Interview with Julia P., Fortunoff Video Archive, Yale University, October 25, 1986. Translation from Yiddish from the partial transcript. Accession number HVT-774. Segment 20.

- That same year, Pirotte photographed Carmelite nuns at their cloister to make ID cards for the Germans. The nuns would not allow a male photographer to enter the cloister, so Pirotte was sent by German authorities to take the photographs.

- Hanna Diamond and Claire Gorrara, “Reframing War: Histories and Memories of the Second World War in the Photography of Julia Pirotte,” Modern and Contemporary France, Vol. 20 Issue 4: Gender, Politics, and the Social in the Historical Perspective: Essays in Honour of Sian Reynolds (2012), 453-471.