Ethan B. Katz

University of California, Berkeley

Few films have retained their political force like Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966). Banned on French television until 2004 and rarely shown in theaters for decades, the film has long been, for myriad radical groups, at once a kind of political manual and a source of inspiration. It also became popular viewing for American military and foreign policy officials in the context of the U.S.’s invasion of Iraq in 2003. That such diverse actors have found the film so instructive for so long speaks to the work’s extraordinary capacity to hold up multiple realities in the history it conveys.[1]

The film is based upon the war memoirs of FLN member Saâdi Yacef (who himself has a major on-screen role in the film as El-Hadi Jaffar), and large portions of the picture’s financing came from the young Algerian state.[2] Nonetheless, Pontecorvo endeavored to depict the French-Algerian War in all of its complex horror, not to make a propaganda piece. Shot in black-and-white on location, the film has the feel of a documentary. Centering on the actual guerilla fighter Ali La Pointe of the National Liberation Front (FLN), the film tells the story of the growth, potency, and violence of the Algerian movement for independence in the capital city of Algiers, and of its eventually brutal repression by the French military.

The film is based upon the war memoirs of FLN member Saâdi Yacef (who himself has a major on-screen role in the film as El-Hadi Jaffar), and large portions of the picture’s financing came from the young Algerian state.[2] Nonetheless, Pontecorvo endeavored to depict the French-Algerian War in all of its complex horror, not to make a propaganda piece. Shot in black-and-white on location, the film has the feel of a documentary. Centering on the actual guerilla fighter Ali La Pointe of the National Liberation Front (FLN), the film tells the story of the growth, potency, and violence of the Algerian movement for independence in the capital city of Algiers, and of its eventually brutal repression by the French military.

The film chronicles the arc of the French-Algerian War (1954-1962), France’s most brutal and emblematic struggle in the process of decolonization. The Battle of Algiers, where most of the film’s action takes place, began in late 1956 as the insurgents mounted an increasingly effective campaign of terror and propaganda. In early 1957, general Jacques Massu and an elite division of paratroopers were deployed to Algiers to crush the rebellion there. By the early fall, following a campaign that included the use of torture and other extra-legal measures, the French military had fulfilled its mission. But this success on the battlefield would be short-lived, as political crisis mounted at home. In spring 1958, the war helped to bring a dramatic end to the Fourth Republic after a military putsch led to the installation of Charles de Gaulle as president. The General ushered France into the era of the Fifth Republic and, in time, he concluded that Algeria should be granted autonomy, and eventually, independence. This decision, viewed by many of his conservative supporters as a shocking betrayal, provoked bitter opposition among both the Algerian colons and many military officers. In early 1961, members of these two groups formed the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS). The OAS waged a last-ditch campaign — against both the army and the FLN — to keep Algeria French at all costs. Eventually, after a series of protracted negotiations, France and representatives of the FLN signed the Evian Accords in March 1962 that paved the way for Algeria’s independence by July 1962.

Two years after the war’s end, former FLN fighter Saâdi founded Casbah Films and approached Pontecorvo to propose making a film about Algeria’s successful struggle for independence. His promised financial backing from the Algerian government offered a significant enticement, but Pontecorvo sought and secured total artistic control. The making of the film was hardly conventional. Aside from the French actor Jean Martin as Lieutenant Colonel Philippe Mathieu, no professional actors appear; several roles are played by veterans of the revolution like Saâdi. The audience’s realization that it is not watching a typical cast, as well as the raw effect created by the hand-held camera used by Marcello Gatti to shoot the entire film, enhance the sense of authenticity.[3]

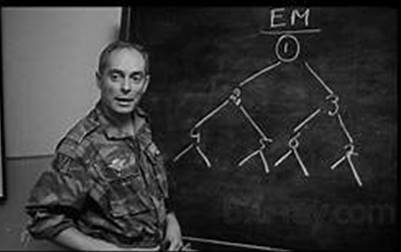

Numerous qualities make The Battle of Algiers extremely effective in the classroom. It offers realistic and powerful depictions of numerous important historical topics of the era: the profound injustices of the colonial system; the emotional register that underlaid the cause of national liberation; the destruction rendered by both sides in the Algerian conflict, including cringe-inducing moments of both torture and terror; Algiers as a physical space of urban life and death; the mechanics of insurgency and counter-insurgency; and the limitations of military success in the face of popular revolt. The film often has the pacing and suspense of a thriller, keeping the viewer engaged.

Yet The Battle of Algiers also operates on at least two other levels that are less widely known, and on which I want to focus here. First, though it has not typically been understood as such, I would like to suggest that it is in some manner a Holocaust film.

Yet The Battle of Algiers also operates on at least two other levels that are less widely known, and on which I want to focus here. First, though it has not typically been understood as such, I would like to suggest that it is in some manner a Holocaust film.

What is perhaps the most iconic monologue of the film is a powerful illustration of the degree to which references to World War II and the Holocaust became ever-present in the Algerian struggle for independence.[4] It features the French commander, the enigmatic Colonel Mathieu, defending himself and his comrades against accusations of torture and barbarism. He exclaims:

We are neither madmen nor sadists. Those who call us fascists today forget the important role that many of us played in the Resistance. Those who call us Nazis perhaps don’t know that some of us survived Dachau or Buchenwald.

This clip, and my own research findings on the politics of memory during the Algerian War, were on my mind the first time that I taught The Battle of Algiers nearly a decade ago.[5] Among the issues I asked my class to consider as they watched the film were thus possible references to World War II and the Holocaust.

Yet I was unprepared for the insight offered by one student, who called our attention to how the film’s opening scene might be read in this context. The film begins with Ali La Pointe and his family hiding behind fake tiles in the wall of their home, seeking to make no sound with their breathing, as French officers approach to take and arrest them. Much of the film is then structured as a flash-back that leads us back to this climactic moment. It is a scene that builds tension for the viewer, and that cultivates instant sympathy for those hiding there, as we hope they will go undiscovered. My student noted that the scene reminded her immediately of dramatic renderings of Jews hiding from the Nazis that she had previously watched, such as George Stevens’ film version of The Diary of Anne Frank (1959).

Yet I was unprepared for the insight offered by one student, who called our attention to how the film’s opening scene might be read in this context. The film begins with Ali La Pointe and his family hiding behind fake tiles in the wall of their home, seeking to make no sound with their breathing, as French officers approach to take and arrest them. Much of the film is then structured as a flash-back that leads us back to this climactic moment. It is a scene that builds tension for the viewer, and that cultivates instant sympathy for those hiding there, as we hope they will go undiscovered. My student noted that the scene reminded her immediately of dramatic renderings of Jews hiding from the Nazis that she had previously watched, such as George Stevens’ film version of The Diary of Anne Frank (1959).

Indeed, the resemblance is uncanny. Stevens’ film had appeared just a few years before, to wide audiences and considerable acclaim. Moreover, director Gillo Pontecorvo was himself a secular Jew and a former wartime resister. He long took particular pride in his previous film, Kapo (1960), set among Jewish inmates in a Nazi concentration camp. By linking implicitly the freedom fighter protagonist at the center of The Battle of Algiers to Jewish victims of the Nazis, Pontecorvo suggests that whatever his faults, Ali La Pointe and his comrades occupy the moral center of the story, and that their opponents are allied with the forces of fascism and tyranny.

In this manner, we can see The Battle of Algiers as emblematic of the “multidirectional memory” that Michael Rothberg has identified as a hallmark of the way that the Holocaust was invoked in this period.[6] That is, in both the opening sequence and the famous speech from Colonel Mathieu, the film appropriates the memory of the Shoah, but it does so in a way that at once honors the victims of genocide and seeks to elicit sympathy for the participants in the current conflagration. (Such a realization does have the un-intended consequence, meanwhile, of highlighting one of the film’s few shortcomings: its total lack of any live Jews as characters, despite the important Jewish population in Algeria that faced difficult choices throughout the war.)[7]

In this manner, we can see The Battle of Algiers as emblematic of the “multidirectional memory” that Michael Rothberg has identified as a hallmark of the way that the Holocaust was invoked in this period.[6] That is, in both the opening sequence and the famous speech from Colonel Mathieu, the film appropriates the memory of the Shoah, but it does so in a way that at once honors the victims of genocide and seeks to elicit sympathy for the participants in the current conflagration. (Such a realization does have the un-intended consequence, meanwhile, of highlighting one of the film’s few shortcomings: its total lack of any live Jews as characters, despite the important Jewish population in Algeria that faced difficult choices throughout the war.)[7]

This brings us to the second level, one that might itself be termed multi-directional in a broader sense. While the film is in many ways highly sympathetic to the Algerian rebels – it repeatedly depicts their courageous fight in the face of oppression and implies that Algeria is a “nation-in-waiting” that finally achieves its independence in the final frames – Pontecorvo offers a decidedly mixed portrait of both the colonized rebels and the forces of the colonizer.

This brings us to the second level, one that might itself be termed multi-directional in a broader sense. While the film is in many ways highly sympathetic to the Algerian rebels – it repeatedly depicts their courageous fight in the face of oppression and implies that Algeria is a “nation-in-waiting” that finally achieves its independence in the final frames – Pontecorvo offers a decidedly mixed portrait of both the colonized rebels and the forces of the colonizer.

Colonel Mathieu’s aforementioned monologue is among a number of moments that seek to avoid a caricature of the French officers as demonic imperial thugs. The messiness of France as colonizer is on display from an early scene depicting torture. The victim, after agreeing to show the French Ali La Pointe’s hideout, is befitted with an army uniform, and as the hat is placed on his head, one French soldier snaps with more than a touch of snark, “Intégration!” (He is rebuked by a fellow soldier.) For the knowledgeable viewer, this is an unmistakable reference to the policy of “integrationism,” a wartime policy that used a variety of means, including American Affirmative Action-like quotas, to try to accelerate efforts toward greater equality for Muslims in Algeria.[8] That the word is used in the context of torture inflects the moment with a biting and powerful irony. Not long after, another scene depicts a European who deliberately trips La Pointe in a way that appears typical of many colonists’ attitudes toward the Muslim population. Yet a French policeman quickly protects La Pointe. What many of the colonized long saw as “the two Frances” are on vivid display here and elsewhere. Most famously, in one well-known scene, three Algerian Muslim women dress as Europeans and plant handbags with bombs in three locations in the European quarter. As the timer on the last bomb ticks down, the camera zooms in on the face of a European infant eating ice cream, who the viewer knows is among those about to be blown to smithereens. After the bomb explodes, the soundtrack briefly features the same melancholic music heard elsewhere in the film– following acts of death and destruction orchestrated by the French against Muslims.

By the same token, the film shows a remarkable appreciation for key nuances in the history of the FLN, anticipating key findings of scholarship published decades later. Early scenes show members of the group taking a hard line against drugs, prostitution, and other vices. Another displays the brutality of which the nationalists were capable, as Ali La Pointe threatens and then kills in cold blood his former friend when the latter resists pressure to join the insurgency. Immediately after, we witness a wedding between two rather young-looking Muslims, performed in secret under the auspices of the FLN, with the officiant adding to the eeriness by stating explicitly that due to the colonial conditions, the FLN “has to make decisions concerning the civil life of the Algerian people.” Here, then, we see an FLN bent on unity at all costs, seeking tight surveillance and control over the behavior of its people.[9]

The film also makes clear that the military victory of the French in the Battle of Algiers was total and devastating. Leading actors on both sides highlight the importance of the United Nations, the international press, and the political will of the French government to the war’s ultimate outcome. Pontecorvo seemed to understand already a short few years after the war that the Revolution was not won primarily with terror and weapons, but by moving the opinion of statesmen and publics in crucial and disparate locations.[10]

Thus The Battle of Algiers remains ripe for opening up multiple interpretations and discussions in the classroom, around not only the French-Algerian War, but wider issues of colonialism and revolt, terrorism and repression, Holocaust memory, international activism and violence, and relations between the Global North and South and the West and Islam. For all of its harrowing drama and historical insight, it is perhaps the film’s multi-directional moral compass that is its most important gesture, particularly in our classrooms today. Many have lamented the ways in which a kind of facile and self-righteous certainty inflects both sides in so many of our political debates, and in turn in the way that many students are currently inclined to read historical developments and texts. But The Battle of Algiers offers a penetrating reminder that even in struggles against brutal oppression, there are human beings on each side, and that both the powerful and the powerless retain the capacity simultaneously for dignity and darkness.

Gillo Pontecorvo, Director, The Battle of Algiers, 1966, b/w, 121 min, Italy, Algeria, Casbah Film, Igor Film.

NOTES

- See Stephen J. Whitfield, “Cine Qua Non: The Political Import and Impact of The Battle of Algiers,” LISA e-journal – Literature, History of Ideas, Images and Societies of the English-speaking World, Vol. X, no. 1 (2012): 250-70.

- Saadi Yacef, Souvenirs de la Bataille d’Alger (Paris: Julliard, 1962).

- Whitfield, “Cine Qua Non.”

- See esp. Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009).

- See Ethan B. Katz, The Burdens of Brotherhood: Jews and Muslims from North Africa to France, chaps. 4-5

- Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory.

- See esp. Katz, The Burdens of Brotherhood, chaps. 4-5; Maud S. Mandel, Muslims and Jews in France: History of a Conflict, chaps. 2-3; Pierre-Jean Le Foll Luciani, Les juifs algériens dans la lute anticoloniale: Trajectoires dissidents (1934-1965) (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2015).

- Todd Shepard, “Thinking between Metropole and Colony: The French Republic, ‘Exceptional Promotion,’ and the ‘Integration’ of Algerians, 1955-1962, in The French Colonial Mind, ed. Martin Thomas (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 298-323.

- Such is one of the central arguments of one of the most important histories of the FLN: Gilbert Meynier, Histoire intérieure du FLN, 1954-1962 (Paris: Fayard, 2002).

- On this point, the film appears to anticipate some of the key findings of Matthew Connelly, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post-Cold War Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).