Amy Freund

Southern Methodist University

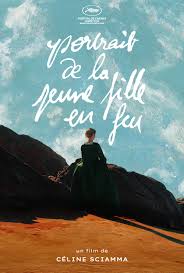

Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (Portrait of a Lady on Fire), directed by Céline Sciamma and released in 2019, is a film about love and art, not necessarily in that order. Set in late eighteenth-century Brittany and Paris, it tells the story of a passionate but brief love affair between Héloïse, a young noblewoman, and Marianne, the female artist hired to paint her portrait. Sciamma constructs her narrative with a remarkable economy: the core story takes place over a few days, involves only a handful of characters (almost all women) moving through a similarly minimal number of spaces, and plays out in restrained dialogue against a silence punctuated (but only rarely) by a two-composition soundtrack. The result is something of an anti-period piece, far removed from the sumptuous historical fidelity of Stephen Frears’s meticulously researched Dangerous Liaisons (1988) or of Sofia Coppola’s arch marriage of 1980s and 1780s excess in Marie-Antoinette (2006). Instead, Portrait de la jeune fille en feu is an utterly convincing romance nested inside a critically acute exploration of the female gaze and female artistic ambition, an exploration that despite (or perhaps because of) its anachronisms provides a surprisingly on-the-nose account of artistic practice in late eighteenth-century France.

The film opens in Marianne’s studio in Paris where she is posing for her female students as part of a drawing lesson. The opening shot, in which a woman’s hand sketches on a surface that is also the rectangle of the camera’s frame, establishes one of the film’s guiding analogies: between the work of the female artist in the eighteenth century and Sciamma’s own filmmaking. Marianne, looking out at the circle of students, is disturbed by the sight of one of her own canvases, a scene of a woman on fire walking on a beach, which has been brought out of the reserves by one of the girls. The canvas (more Belgian Surrealism than eighteenth-century French genre painting) provokes the flashback that will structure the entire film.

We move immediately to a moment in the recent past. Marianne has been hired by a wealthy noblewoman living on an island off the Breton coast to paint a portrait of her daughter Héloïse, who has been promised in marriage to a Milanese aristocrat. The problem is that Héloïse, fresh from the convent, has no interest in marriage or in sitting for a portrait which is intended to serve as her presentation to her future husband. Marianne is introduced into the household as a companion and charged with painting a portrait in secret. By the time Héloïse discovers the deception, she and Marianne have already established an emotionally charged friendship that, when her mother leaves the island for a few days, becomes a passionate love affair. During this brief but enchanted interlude, Marianne, Héloise, and the servant girl Sophie live in an ideal Republic of Women. They eat, drink, and smoke together, play cards, read Ovid’s story of Orpheus and Eurydice, participate in a joyous and obscurely witchy gathering of local women around a bonfire, paint a new version of the portrait, procure an abortion for Sophie, and (in the case of Marianne and Héloise) live out a romantic and sexual idyll. All this is abruptly brought to an end by the mother’s return. Marianne must leave the island and the portrait, and Héloïse must go to her future husband in Milan. After their wrenching parting, couched in Ovidian terms, Marianne returns to Paris and her career. Sciamma concludes the film with twin scenes of artistic creation and spectatorship: at the public Salon exhibition, at which Marianne exhibits (under her father’s name) an ambitious history painting on the theme of Orpheus and Eurydice and sees another artist’s portrait of Héloïse as a wife and mother, and at a public concert, where Marianne catches a glimpse of Héloise, profoundly moved by the power of music.

Sciamma’s vision is twofold. On one hand, it is a celebration of passionate love and solidarity between women, and of the possibility of a female-made utopia. On the other hand, it is a manifesto about the power of art and particularly about the power of art in the hands of women. These two visions are entirely intertwined. Marianne and Héloïse’s love can ultimately only exist in and through art, and the society they build in their brief idyll combines sex, friendship, and artistic ambition. Sciamma’s insistence on the female gaze, moreover, draws our attention to the ways in which looking at women, and looking by women, structures art production and gender hierarchies alike.

So what does this formally beautiful love story offer scholars and students of French cultural history? It does not provide a faithful recreation of eighteenth-century interiors or a particularly accurate picture of eighteenth-century sociability or marriage practices. Its female protagonists make historically improbable choices (leaping into the ocean fully clothed to rescue a crate of stretched canvases, experimenting with psychedelic drugs, attending a public musical performance alone). Its costuming is only intermittently period-correct and its blindness to class hierarchies is wildly optimistic. The film, however, does provide a compelling evocation of artistic practice, and particularly portraiture, in late eighteenth-century France – both on a technical and a theoretical level. Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s memoirs of her artistic career are cited in the credits, and it is clear that Sciamma has also carefully studied art historical accounts of the period. Her depiction of portrait-painting, from the preparation of canvases to the conventions of posing to the obstacles to female artistic success, conform closely to the historical record. Sciamma, moreover, provides a subtle analysis of the social and psychic dynamics of portraiture, particularly the reciprocity of the portrait encounter. The result is one of the most sustained and convincing recreations of eighteenth-century artistic experience I have seen on film.

Formally, Portrait de la jeune fille en feu also rewards close attention. Sciamma insists throughout on the parallels between film and canvas, from the multiple frames establishing the identity of canvas and screen to the repeated composition of shots of the three female protagonists as bust portraits. Sciamma’s overt and implied visual references resonate profoundly with eighteenth-century visual culture: sparsely-populated and dimly lit kitchen scenes that evoke Jean-Siméon Chardin’s domestic genre paintings, quotations of late eighteenth-century portraits by Jacques-Louis David and Vigée-Lebrun, even juxtapositions of the brunette Marianne’s and blonde Héloïse’s heads and bodies that recall François Boucher’s erotic scenes of goddesses and nymphs. The film’s formal rigor is thematic as well as visual; for instance, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice – the artist and the lost beloved – echoes throughout the film, as a way to think through desire, loss, memory, artistic genius, and the risks and rewards of asking for the impossible. The intertextuality of the film extends to the heroines’ names: “Sophie” and “Héloïse” invoke Rousseau’s meditations on the female self and society, while “Marianne” simultaneously recalls Marivaux’s novel of sensibility, the allegorical representation of the French nation, and real-life eighteenth-century portraitist Marianne Loir.

Portrait de la jeune fille en feu is, in short, both a historical film and an ahistorical one. It imagines, within the frame of real constraints on female agency, ambition, and desire, a utopian eighteenth-century parenthesis. It creates a world in which – for a brief moment – same-sex desires are fulfilled and fulfilling, women forge links of solidarity across class lines, the female gaze is the only gaze, and art is a source of power for all. Marianne not only paints a successful portrait of her lover, but Héloïse also pushes her to compose a history painting about abortion, with Héloïse and Sophie as models. Marianne teaches Héloïse to paint. The local women perform a polyphonic song, equal parts traditional Breton folk music and twenty-first century call and response, around a blazing bonfire – a gathering at which Héloïse’s dress catches fire, providing the titular image of the film and a metaphor for the incendiary powers of art and desire.Sophie is revealed to be a exquisite needleworker, recreating freehand the bouquet of wildflowers and herbs that ornaments the communal kitchen. Sciamma, however, is clear-eyed about the unsustainability of this community in the eighteenth century. All that is left, once Héloïse’s mother returns to the island and brings the real social order with her, is art. Its liberatory powers bring Marianne professional success in Paris, but art must also carry the burden of sublimating Marianne’s and Héloïse’s desires.

The film, as visually satisfying and thematically complex as it is, occasionally rings false. The dress that Héloïse is painted in is an acid green that would astonish eighteenth-century dyers. Marianne’s portrait of Héloïse, which effectively functions as a fourth protagonist, is jarringly Belle Epoque in its style and execution, more Cecilia Beaux than Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. The scene in which Marianne executes a nude self-portrait with the help of a mirror propped up in her lover’s crotch does no favors to Sciamma’s nuanced meditation on the female gaze. These anachronisms and overstatements, however, do no real harm to a film that depends for its effect on the juxtaposition of modern feminist theory with a historical moment that allowed few possibilities for female agency and desire. Portrait de la jeune fille en feu is a formally beautiful and richly nuanced story, recounted in sparse but elegant language accessible to a French learner, that powerfully conveys the real accomplishments of eighteenth-century female artists. The film also yields even greater intellectual and aesthetic rewards, immersing its viewers not only in the world of the female artist in the late eighteenth century but also in feminist debates about sexuality and visuality rooted in contemporary theories of gender. The resulting revisioning of French art and history is a provocation that will resonate with scholars and students alike.

Céline Sciamma, Director, Portrait d’une jeune fille en feu [Portrait of a Lady on Fire], 2019, 122 min, color, France, Lilles Films, Arte France Cinéma, Hold Up Films