Jeffrey B Hobbs

I last visited Provence about a year ago when I took a day trip to Avignon in the middle of July. Originally headed for Aix, my train’s destination changed in the middle of my journey as French trains are wont to do. After leaving the station, I quickly found myself lost in the bustle of the Festival Avignon with crowds of visitors and residents wandering the city on a sweltering Saturday. Temperatures that July routinely reached 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Everywhere I walked I was greeted by a wall of heat and the inescapable din of cicadas that drowned all human activity on the streets. I was therefore not surprised when Jean Giono opened his 1951 novel Le hussard sur le toit with the mysterious protagonist, Angelo Pardi, wandering through a parched and sterile Provence countryside pursued unrelentingly by sunlight and surrounded by a hostile nature.

Out of this hellish landscape, which Angelo crosses with the bravery of a soldier facing a mortal foe, slowly arises the specter of a more terrible manifestation of nature, an unnamed sickness, that quickly overcomes its victims. Driven by the heat into fields, the inhabitants of Provence seek relief in a mania for melons, apricots, and tomatoes that spread the mysterious illness. Amid this silent and invisible natural disaster, Giono’s young cavalryman finds a country inn and, tired from his journey and unaware of looming horrors, drinks four bottles of wine before falling into an untroubled sleep. The heart of Giono’s novel rests in this contrast between the detached coolness of Angelo and the human tragedy that unfolds around him. Angelo is the reader’s guide through what we learn is an outbreak of cholera in Provence in the 1830s. He witnesses the terrible toll the disease has on its victims, strewn across the countryside and city streets, and the desperation and hopelessness the living feel as the epidemic unfolds.

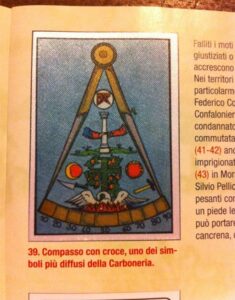

Giono provides Angelo with a backstory and motivation. He is a member of the Piedmont Carbonari and a noble cavalry officer who fled Italy after a botched assassination of an informer, the baron Swartz. Unable to carry through with the Carbonari plot, he instead challenged Swartz to a duel, killing him according to his code of honor. He journeys across Provence to find his childhood friend, Giuseppe, who has received delivery of money from Angelo’s wealthy mother. Although this long-awaited meeting occurs halfway through the novel, Angelo soon parts with Giuseppe and his political allegiances do not greatly impact his fate. What truly defines Angelo is his constancy in the face of death, danger, and the horrors of the epidemic. Throughout the novel, he shows himself to be indefatigable in the face of hardship, selfless towards others who suffer, honorable to those who deserve his honor, and impetuous in fighting his foes. If Giono had been writing in the 1830s, and not the 1950s, one could be excused for thinking that the character of Angelo was propaganda for the Carbonari to make them appear as paragons of honor, toughness, selflessness, and idealism. However, despite Angelo’s outward bravado and coolness, Giono provides the reader with a window into the thoughts of his protagonist that shed a more critical light on his identity and his motivations.

Angelo’s first engagement comes in a small village that has been ravaged by cholera and in which remain only the cadavers of its victims and the animals they have attracted. Approaching the village, he finds a woman who has fallen prey to cholera in the middle of the road enveloped by crows. His first reaction to the sight is to vomit until he remembers how veteran officers might judge him for his squeamishness. Collecting himself, he ventures into a nearby home where he is attacked by a flock of birds and a vicious dog before discovering three more victims. However, the sight of another crow carrying out its ghastly feast pushes him over the edge. He runs out of the house stumbling confusedly surrounded by houses that “lui paraissaient très irréelles.” (51) Angelo’s first experience with the epidemic serves as a trial by fire in which he struggles to live up to the identity as the courageous military man he has imagined for himself. He is helped by the appearance of a young doctor who valiantly attempts to save a survivor before dying himself. The young doctor teaches Angelo how to treat cholera victims, but also helps him overcome his initial terror of the death surrounding him. For the rest of the novel, Angelo takes precautions against the disease, but no longer fears his own death or the proximity of the dead.

Once Angelo has steeled himself against the disease, the true antagonists of the novel present themselves, the living. After fleeing the ravaged village, he encounters a series of barricades that make him decide: “Il faut faire ici comme en pays ennemi.” (79) He quickly discovers that government authority has faltered and that the forces of order have adopted a punitive approach of rounding up travelers into “quarantines” which the majority never leave. The absence of authority can be seen in the image, later in the novel, of an infected French cavalry officer riding alone and directionless through a field, on the verge of death. (321) Without government direction, the inhabitants of Provence are overtaken by a fear that draws out the worst in human nature. On arriving in the town of Manosque, Angelo is seized by an angry mob who accuse him of being a government spy sent to poison public fountains. We find out later that the leader of this mob, Michu, had been paid, with Angelo’s own coins, by Giuseppe, to spread rumors of a government conspiracy to destabilize the political situation in France. (264) Freed by the remaining town officials, Angelo is again chased by vigilantes before finding refuge on the town’s roofs. From this vantage point, he witnesses a community in the process of disintegration: a crowd beating to death a man in the streets, cholera victims falling dead while going about their business, and groups wandering the streets shouting to each other about natural portents of disaster, such as comets and clouds.

On the titular roofs, Angelo has his own crisis of faith in humanity as well as his identity. Resting from his trials in the streets below, he reflects that “les hommes sont bien malheureux…Tout le beau se fait sans eux…ils écument de jalousie ou périssent d’ennui…” (136) However, unlike the inhabitants of Manosque, who had become dispirited and cruel facing death and fear, Angelo does not fall into despair because of his pride in republican values and military honor. Instead of being frightened by the violence and roving mobs, he fears how his fellow officers would judge his actions. This connection to his former life allows him to observe the events around him with detachment and to feel compassion towards the people below. He decides the townspeople’s obsession with supernatural or paranoid explanations of the epidemic is a human response to loss. (159) While others cope with conspiracy theories or omens, Angelo transforms the epidemic into a military campaign in which he must show his valor and honor. Giono reinforces this coping mechanism through the use of military language to describe Angelo’s thoughts while on the rooftops. Watching a crew of men collecting dead bodies, Angelo is shocked to see all three fall ill and collapse on the road. Giono describes Angelo’s reaction as if he was looking through field glasses during a campaign: “Cette entreprise délibérée de la mort, cette victoire foudroyante, la proximité du champ de bataille qui restait sous ses yeux, impressionnèrent fortement Angelo.”(165) Traveling the roofs of the town, Angelo is offered a mental respite in which he comes to terms with the scenes of horror around him.

Angelo’s time in Manosque is also marked by two important events that strengthen his identity as an honorable and idealistic young man. Having to descend in search of food, he encounters a young woman, who we later find out is the Marquise de Théus, who has been trapped alone in the town. Caught unaware by the appearance of a living woman, Angelo’s first reaction is to declare his honorable nature: “Je suis un gentilhomme.” (178) Invited by the Marquise to share tea, he spends their time together embarrassed by his appearance and anxious not to seem a threat. Declining to stay the night, he has trouble sleeping worrying whether he has infected her.[1] Later in the novel, he will be reunited with the Marquise and spend the rest of his journey escorting her safely home. The Marquise provides Angelo with an anchor that allows him to rekindle his chivalrous identity amid the chaos of the epidemic. Soon after meeting the Marquise, he descends from the rooftops and meets an elderly nun who has taken it upon herself to care for the town’s dead. These cholera victims were often found in their last hiding places or abandoned on the street by family members attempting to keep their homes free of infection. Angelo joins the nun in her daily labors, collecting the dead and washing them in nearby fountains. He connects this dangerous and terrible work with his sacrifices for the republican cause. He recognizes that his motivation for helping the nun and fighting for liberty comes ultimately from pride: “Il est incontestable qu’une cause juste, si je m’y dévoue, sert mon orgueil.” (206) He adds, “Mais, je sers les autres.” Chased to the rooftops of Manosque, Angelo finds there two roles that strengthen his identity as an honorable man as others falter because of fear: chivalrous protector and caretaker of the dead and dying.

After leaving the town, Angelo quickly finds Giuseppe, collects his mother’s funds, and sets off alone with the plan to meet Giuseppe again at the Italian border. However, he is blocked by barricades and reunites by chance with the Marquise. He decides to help the Marquise return safely home. On the road, they face dangers posed by people who have been made cruel, hopeless, or desperate by the epidemic. Although the Marquise is an able fighter, equipped with two formidable pistols, Angelo relishes the opportunity to show his military acumen as her protector. Trapped by cavalry, they are sent to quarantine in a tower in Vaumeilh. The tower is watched by apathetic nuns and only thirty-eight of one hundred and twelve captives have survived in confinement. While the others waited patiently for their fate, Angelo leads an escape that renders him “très heureux et extrêmement loin du cholera.” (393) Later on the road, they shelter on the land of an isolated rural family whose hospitality turns out to be a ruse to rob them of their valuables. The thought of a possible battle with the family excites Angelo: “Ce petit air de guerre où il n’y avait à craindre que des coups de feu le réjouissait.” (412) His military pride is hurt when a traveler explains to him: “Les soldats sont des gens comme les autres. Au fond, ils détestent la mort…Mais il y a l’uniforme.” (423-4) Angelo is finally given his heroic moment as they near Théus when the Marquise falls sick with cholera. He jumps to her rescue, using all the knowledge he gained during his travels, to save her. Importantly, alone in the woods tending to the Marquise, he feels real fear for the first time: “Il s’étonnait, il s’effrayait même un peu du vide de la nuit. Il se demandait comment il avait pu ne pas avoir peur jusqu’ici et surtout de choses si menaçantes.” (492) The Marquise survives the night thanks to Angelo’s tireless care. The next day, a former servant of the Marquise finds them and the two are transported to safety. By saving the Marquise, Angelo accomplishes his great act of heroism and turns his eyes back to Italy overwhelmed with happiness.

Giono’s novel offers a strange juxtaposition between the brutal and disturbing images of the ravages of cholera and the naïve courage of the protagonist, who returns home seemingly unchanged by his traumatic experiences. Once the Marquise is safe, Angelo thinks only about his new horse, verdant mountains, and his homeland. Having just saved a woman inflicted with cholera, he does not worry much about spreading the disease: “On ne pouvait imaginer de contagion susceptible de s’attaquer avec quelque chance de victoire à ces hommes et femmes simples…” (497) Although he willingly endangers himself for others, he does not connect the suffering of cholera victims with his own experience and is driven more by a sense of duty than compassion. He views impersonally the pain and grief of the inhabitants of Provence just as he sees the plight of the people abstractly as the son of an Italian princess. For example, fleeing the quarantine tower, Angelo was able to visualize “avec précision les agonies et les morts qui devaient continuer à désoler les lieux habités.” (405) Only when the Marquise, one of the few characters for whom he had developed personal feelings, falls ill does he connect the specter of death with his own existence and his courage briefly fails. Viewing himself as superior to others, he pities the dead and dying, passes judgement on the living, and encounters one victim after another with little emotional response. In his 1959 New Yorker review of the sequel, Le Bonheur fou, Anthony West lamented that Giono’s protagonist had undergone a transformation into a comic western hero that appeared like “Buster Keaton at his best” and “John Wayne at his worst.”[2] West attributed this change to Giono’s dubious connections to the Vichy regime and the author’s distrust of “liberation movements…liberal and democratic politicians…and liberal ideas.”[3] These character traits were already present, if less pronounced, in the first novel. When faced with weak resistance, Angelo routinely employs a mix of bravado and threats to force his opponent to surrender. In one incident, he disarms a quarantine guard who responds indifferently explaining he was always free to go and shows him the best route of escape. (98)[4] In contrast, when he faces real threats, especially from the military, he quickly flees or yields, cursing his assailants. If West is to be trusted that Angelo devolved by 1848 into a swashbuckling hero, it would not be a major break with Giono’s earlier characterization.

The searching questions Angelo asks while caring for the dead with the nun therefore seem to pass without making much of an impact. In that moment of self-reflection, he nevertheless uncovered an important character trait: the critical distance he maintains between himself and the people he encounters. When working with the nun in Manosque, Angelo engages in an internal monologue that demonstrates his own sense of superiority and self-interestedness. He sees cleaning the dead as “inutile” since “ils pourriraient aussi bien sales que propres.” (203) However, he helps the nun because he demands “des preuves incontestables” of his superiority over “tous ces gens qui avaient des positions sociales, à qui on donnait du ‘monsieur’ et qui vont jeter leurs êtres chers au fumier.” Thinking back to the first village, he asks why the young doctor had sacrificed his life to help the dying and wonders if “il était là pour faire son devoir ou pour se satisfaire.” (205) He admits he had been jealous of the young doctor’s courage and had helped him to prove they were equals. Returning to cleaning the dead, he decides that he and the nun are driven by self-interest, “Nous voilà seuls dans la nuit avec ce travail dégoutant mais qui nous met en grande estime de nous-mêmes…Nous avons besoin de faire quelque chose qui nous classe.” (206) In this passage, Angelo shows a remarkable ability to analyze his own motivations without escaping the egotism that drives him. While accepting his self-interested motives, he projects them onto the two most altruistic characters in the novel, the young doctor and the nun, so that they do not seem better than him. However, contrary to Angelo’s assessment, the nun washed the dead “de préparer les corps pour la résurrection” and “les voulait pour cette occasion propre et décents.” (207) She worried that God would judge her for not doing her duty and showed humility saying to herself, “Je suis une femme de ménage. Je fais mon métier.” Surrounded by a city full of suffering, Angelo cannot see beyond his own striving for heroism and distinction. He washes the dead as a futile exercise to prove his own worth and robs the young doctor and nun of altruism to justify his egotism. Giono writes forgivingly of Angelo: “Il y avait très peu de laideur dans son orgueil. Tout au moins, à peine ce qu’il en fallait pour qu’il soit humain.” (204) In the novel, the author investigates two types of egotism: the egotism of self-preservation that drives the cruelty and fear of the masses and heroic egotism that blinds Angelo to the altruistic virtues of love and humility.

Giono’s Hussard sur le toit provides the reader with a critical perspective on political idealism and activism that resonates beyond the historical context of the 1830s. Angelo is a young idealistic cavalry officer and member of the Carbonari who is inspired by masculine codes of honor and a sense of adventure. He is also a symbol for a type of political activism that values the virtue of the individual over lasting improvements to injustice. Throughout his journey, Angelo mixes musings about his devotion to liberty with criticism of the everyday people he meets. He decides that France is probably hopeless because “il y a ici du mal et du bien que nous ne pourrons pas réformer et qu’il vaut probablement mieux que nous ne reformions pas.” (350) Taking stock of Giuseppe’s and Angelo’s actions, we see an equivocal mix of good intentions and morally questionable choices. Before his camp is ravaged by cholera, Giuseppe sowed discord and fear in Manosque producing dire consequences for the people for whom he supposedly fought. By the time he departs France, Angelo has accomplished chivalrous deeds for women and children, washed the dead in Manosque, and helped the Marquise return home. However, he acts bravely primarily to satisfy his pride rather than out of genuine compassion for others. In a stable on the road, a stranger tells him that egotism, not hate, is the opposite of love and that the two of them, sleeping next to their horses and hoping to flee the epidemic, could not pretend “nous aimions beaucoup notre prochain.” (338) Riding off to Italy with a head full of dreams, Angelo leaves behind a France that is not better or worse off than before except for the small acts of kindness he offered to those who suffered immediately before him.

Jean Giono, Le hussard sur le toit, Paris: Gallimard, 1951

NOTES

- Cholera’s waterborne spread was not theorized until 1849 and not proved until 1884. See Sheldon J. Watts, Epidemics and History: Disease, Power and Imperialism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 172.

- Anthony West, “An Arrival, A Departure,” The New Yorker, June 20, 1959, 113-116.

- West takes criticism of liberal and democratic movements as evidence of tacit support of fascism. Giono was a well-known and outspoken pacificist in the interwar years because of his experiences as a soldier in World War I. Although his pacifism led to a problematic indifference to German atrocities in World War II, he was averse to any political cause beyond the protection of his region and his town. His ambivalent portrayal of the Carbonari might be due to this skepticism towards outsiders and political movements. For more on Giono’s pacificism, see Peter Fritzche, An Iron Wind: Europe under Hitler (New York: Basic Books, 2016), 34-38. On the question of Giono’s collaboration with Vichy, see Richard Goslan, “Jean Giono et la ‘collaboration’: nature et destin politique,” Les langages du politique, n. 54, March 1998, 86-95.

- For a slightly different interpretation of this egotism, see Anthony West’s 1954 review of the novel in the New Yorker. West argues that Angelo forgets his self-interest in favor of courage and overcomes the “self-love” that inspires mass fear. However, he does not analyze Angelo’s internal monologues that provide insight into the character’s motivations. Anthony West, “The Quick and the Dead,” The New Yorker, January 16, 1954, 93-97.