Jonathan Spangler

Manchester Metropolitan University

This classic comedy from the tail end of one of the classic eras of French cinema stars three of France’s grands hommes of comedy: Philippe Noiret, Jean Rochefort and Jean-Pierre Marielle. But from the very first scene, set on a bleak rocky Breton coast, the viewer knows that the party promised by the Regency that followed the death of Louis XIV is not going well. The English title offered for this film seems to be a mis-translation…I would suggest instead “Let the Party Get Started!.” It reflects better the mood of the film, an almost desperate plea for everyone to have a good time after Louis XIV’s long and expensive reign, within a more historically informed sense of the times, in which aristocrats heaved a sigh of relief after the old man died, hoping that joy and pleasure would return to the Court. The best-known memoirists and letter-writers of the time, the duc de Saint-Simon, Liselotte von der Pfalz, and even Mme de Maintenon, confess that Versailles had turned into a desert with a dreary atmosphere in the last years of the reign of the Sun King.

This film reveals, then, that four years into the Regency of the late king’s nephew, Philippe, duc d’Orléans, the party had yet to truly commence,  that it was only a façade. Deep down, aristocrats were still suffering from boredom or worried about social stresses that were soon to bubble to the surface. The opening scenes show soldiers trying to kidnap girls to send to Louisiana, in a desperate attempt to get that doomed Regency project of settlement there (with shares sold in that prospect) off the ground. We then see the Regent, played by Noiret, observing the autopsy of his daughter, the Duchess of Berry who had just died, it was said, from a dissolute life of drink and over-eating, Courtier tongues wagged that she was also pregnant, despite being a widow, and worse, that it was her own depraved father who had gotten her pregnant.

that it was only a façade. Deep down, aristocrats were still suffering from boredom or worried about social stresses that were soon to bubble to the surface. The opening scenes show soldiers trying to kidnap girls to send to Louisiana, in a desperate attempt to get that doomed Regency project of settlement there (with shares sold in that prospect) off the ground. We then see the Regent, played by Noiret, observing the autopsy of his daughter, the Duchess of Berry who had just died, it was said, from a dissolute life of drink and over-eating, Courtier tongues wagged that she was also pregnant, despite being a widow, and worse, that it was her own depraved father who had gotten her pregnant.

Yet Orléans seems cool and dispassionate about the whole affair. Through most of the film, his predominant emotion is ennui. This is appropriate for him, the most intelligent of the entire Bourbon clan during the louisquatorze era, whose talents and ambitions were quashed at every turn by a king afraid to share any of his gloire with his younger brother the duc d’Orléans, known as Monsieur (the title accorded to a French king’s brother). This feeling extended to Monsieur’s son as well. As duc de Chartres, he had been denied prominent positions in the army, for fear that he might outshine the King’s precious bastard, the duc du Maine (who turned out to be a terrible field commander), and was denied any voice on the Royal Council, for fear of his new ideas about governance. When the Paris Parlement rejected Louis XIV’s will and made him Regent, in September 1715, Orléans did indeed attempt to introduce new ideas, notably a conciliar system (polysynodie) by which royal authority was shared with court nobles and participation in government widened. By 1719, when this film is set, this system had been abandoned due to its perceived flaws (though this view has recently been challenged).[1] The Regent, his idealism crushed, returned to a more centralised and authoritarian form of government. Seemingly unfazed by the death of a daughter whose health at 23 had been so ruined by drink, the Regent resumed his life of pleasure, led by his former tutor and now friend and chief minister, the abbé Dubois (1656-1723), played by Rochefort.

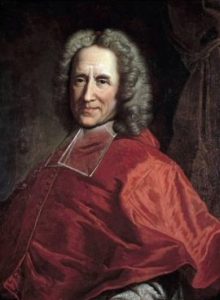

Dubois and Orléans shared a similar appreciation of the joys of libertinage and doubts about the existence of God. As a man of the cloth, Dubois’ cynicism is especially bald-faced, especially as he aimed at ever more prestigious—and financially lucrative—positions in the Church. He became Archbishop of Cambrai, in 1720, and Cardinal in 1721.  All of this is treated as unremarkable: the Regent discusses his life philosophy while viewing pornographic cartoons in a brothel; Dubois talks about his ecclesiastical ambitions while his mistress’s legs are high in the air.

All of this is treated as unremarkable: the Regent discusses his life philosophy while viewing pornographic cartoons in a brothel; Dubois talks about his ecclesiastical ambitions while his mistress’s legs are high in the air.

The broad unbridled sexuality in this film sometimes has a Benny Hill feel to it. This is definitely a French film from the 1970s, with lots of buxom women on display, wearing modern makeup and hairstyles. There are shades of contemporaneous Monty Python or Mel Brooks history films: dead rats lie about the palace, a piss-boy carries a bucket around the gardens… There are wonderful one-liners: a woman invites her Jesuit confessor to a costume ball thrown by the Regent in a brothel, reasoning that “If he sees everything, I won’t have to confess!” (at minute 54:00). There are also inside jokes for historians: when asked if he has a knife, this same Jesuit responds “Not since Ravaillac,” referring to the rogue Jesuit who had assassinated Henry IV in 1610.

Enter a very rustic-looking Breton nobleman, the Marquis de Pontcallec, played by Jean-Pierre Marielle. He has come to Court to protest the treatment of the people of his province, heavily taxed, and now forced to emigrate to populate the new city on the swamps of the lower Mississippi, named of course Nouvelle Orléans after the Regent. Pontcallec’s concerns are brushed aside, and he subsequently leads a rebellion, aiming to form a French republic and to install Philip V (the former duc d’Anjou, now King of Spain) on the throne of France, with the duc du Maine as regent. The contradictions in this plan easily wash over the heads of the plotters. The resulting revolt is heartfelt but disorganized. What they lack in supplies and training, they endeavour to make up for in spirit: when attacked by the royal cavalry, they plan to riposte with apples. They are soon overwhelmed and the marquis is arrested. The Pontcallec Conspiracy (1718-1720), followed on the heels of the failed 1718 Cellamare Conspiracy, which had also meant to reverse d’Orléans’s regency and instal Philip V as king. While the Cellamare plot, involving the Spanish ambassador, the duc du Maine and his wife, and other high-ranking nobles, merely led to the recall of the ambassador to Spain, there were harsher consequences to the Breton revolt. Pontcallec and several other Breton nobles were executed, while the duc and duchesse du Maine had to admit to their participation in the plot.

Enter a very rustic-looking Breton nobleman, the Marquis de Pontcallec, played by Jean-Pierre Marielle. He has come to Court to protest the treatment of the people of his province, heavily taxed, and now forced to emigrate to populate the new city on the swamps of the lower Mississippi, named of course Nouvelle Orléans after the Regent. Pontcallec’s concerns are brushed aside, and he subsequently leads a rebellion, aiming to form a French republic and to install Philip V (the former duc d’Anjou, now King of Spain) on the throne of France, with the duc du Maine as regent. The contradictions in this plan easily wash over the heads of the plotters. The resulting revolt is heartfelt but disorganized. What they lack in supplies and training, they endeavour to make up for in spirit: when attacked by the royal cavalry, they plan to riposte with apples. They are soon overwhelmed and the marquis is arrested. The Pontcallec Conspiracy (1718-1720), followed on the heels of the failed 1718 Cellamare Conspiracy, which had also meant to reverse d’Orléans’s regency and instal Philip V as king. While the Cellamare plot, involving the Spanish ambassador, the duc du Maine and his wife, and other high-ranking nobles, merely led to the recall of the ambassador to Spain, there were harsher consequences to the Breton revolt. Pontcallec and several other Breton nobles were executed, while the duc and duchesse du Maine had to admit to their participation in the plot.

Philippe Noiret plays the duc d’Orléans as witty but always with a shade of melancholy. He even looks like a Bourbon, with regal jowls and a long nose. His Orléans is not only cynical, however: he gently teases the pious and is tender to the young Louis XV; he is also a tender lover regardless of a young woman’s social position (whether prostitute or his god-daughter fresh from a convent)—these reveal that his love of a dissolute lifestyle is really just an act (“You don’t like debauchery, just the noise it makes”). Orléans laments the sequence of deaths it took to bring him to his position as regent, and welcomes the sleep of the grave.

By the end, he goes slightly mad and thinks he already smells like a rotting cadaver. Jean Rochefort portrays the abbé Dubois with a complex combination of seriousness and frivolity. He is a courtier, dissembling, but also disarmingly honest, especially with Orléans. They are old friends, but at the same time, Dubois is blatant about using this friendship to advance his career. As a self-made man, he knows he cannot progress without the protection and support of Orléans. His efforts to say his first mass as archbishop are comical.

By the end, he goes slightly mad and thinks he already smells like a rotting cadaver. Jean Rochefort portrays the abbé Dubois with a complex combination of seriousness and frivolity. He is a courtier, dissembling, but also disarmingly honest, especially with Orléans. They are old friends, but at the same time, Dubois is blatant about using this friendship to advance his career. As a self-made man, he knows he cannot progress without the protection and support of Orléans. His efforts to say his first mass as archbishop are comical.

Jean-Pierre Marielle’s marquis de Pontcallec is incredibly sincere, brave, honest, and in the end unrealistic. He is comic, always carrying an oversized pitchfork with which he plans to lead his army of ragtag Breton nobles.  When the marquis is arrested, he warns his captors to beware of his ‘mistouflet’—the soldier asks “Is that a weapon?” to which Pontcallec responds “Can’t you tell?” (1:08). He is full of artificially inflated self-confidence: a man presented with a stuffed hippopotamus head asks him what animal it is, and the marquis authoritatively announces “an elephant” without even pausing. The character of the marquis is drawn very much in the spirit of Don Quixote, who, in an interesting twist, would be played by Rochefort years later in Terry Gilliam’s catastrophic production, which was never released except in the form of a documentary, Lost in La Mancha, in 2002.

When the marquis is arrested, he warns his captors to beware of his ‘mistouflet’—the soldier asks “Is that a weapon?” to which Pontcallec responds “Can’t you tell?” (1:08). He is full of artificially inflated self-confidence: a man presented with a stuffed hippopotamus head asks him what animal it is, and the marquis authoritatively announces “an elephant” without even pausing. The character of the marquis is drawn very much in the spirit of Don Quixote, who, in an interesting twist, would be played by Rochefort years later in Terry Gilliam’s catastrophic production, which was never released except in the form of a documentary, Lost in La Mancha, in 2002.

The director Bertrand Tavernier is no stranger to the early modern period. After a fairly dull reworking of the Three Musketeers story in the film La fille d’Artagnan (1994), starring Sophie Marceau, he directed a lovely version of the La Fayette novel, La Princesse de Montpensier, in 2010. But back in 1975, Que la fête commence was only his second major film, following the success of L’Horloger de Saint-Paul from the previous year (also starring Philippe Noiret and Jean Rochefort, as well as Christine Pascal, who plays Emilie in this film). Nevertheless, it is clear from the detailed script that he understands the period, and indeed, his writing won him a César award and he also walked away as best director.

Tavernier’s care for detail is demonstrated by the music used in the film, much of it written by the duc d’Orléans himself. A downside to such historical detail, is that many of the characters or events are never fully identified, so if you already know a lot about the Regency period, you get it, but might otherwise get lost. For example, there is a side-plot about the prince de Condé (correctly shown with one eye) which is never clearly introduced. You would need to know about his investment in the financial schemes of the Regent’s economic guru, Scotsman John Law, centered on the colonization of Louisiana. This led to the sale of shares, a financial bubble, and the system’s collapse when buyers demanded the value of their shares in gold. The Prince withdrew huge amounts from Law’s Système, causing it to fail, spectacularly, in 1720, leading to the financial ruin of many. Several people allude to having gone bankrupt in various parts of the film, but they never specify why. Some knowledge of the details concerning the history of paper money and the its subsequent distrust by the French is therefore recommended.

Some details are simply confusing: the comte de Horn enters, a Belgian nobleman and the Regent’s cousin though his mother the Princess Palatine. Riddled with debt, he and a sidekick murdered a stockjobber on the rue Quincampois (headquarters of Law’s bank) order to steal his shares in the Mississipi venture, reputedly worth several hundred thousand livres. For this, and despite the pleas of the high nobility, the two men were broken on the wheel on the Place de Grève, on 26 March 1720. That same day, in Nantes, the marquis de Pontcallec was beheaded along with three of his fellow conspirators, in the standard mode of execution reserved for the nobility. Pontcallec became a hero of the Breton nationalist movement.

When the film gets pensive, it is mostly about memory: how will we be remembered? For these supper orgies? The broader message—germane to the times—is that liberals are fun and somewhat perverse but are genuinely good at the core, and that conservatives (whether the rural Breton nobles or the court conservatives led by the prince de Condé) are boorish bigots. The intellectual Orléans, for example, teases Condé for not recognising a line from a Corneille play (which Condé simply dismisses); Condé confuses America and Africa, and when corrected, casually comments that “they are all darkies (nègres) there.” In contrast, the rural nobleman Pontcallec is depicted as honest yet only half-educated– he spends much of the film dictating letters to the Regent; he has read about the concept of a republic, but isn’t entirely sure what it is.[2] In another cliché, the prostitute Emilie is the one person with genuine moral values.

In the end, the Regent feels bad about having executed a folk hero, realising too late that Dubois made the rebellion into something much more serious than it really was for his own benefit (to obtain his prize, the archbishopric of Cambrai). Suddenly tiring of the lifestyle of the 24-hour party people, Orléans is easily dissuaded from bedding his god-daughter, saying instead that he will “make his garden grow,” in a clear reference to Voltaire’s Candide. And although this novel wouldn’t appear for another four decades, it is a good indicator that Orléans was a man ahead of his time, someone with bold ideas for which his world was not yet ready. He participates, although with less passion, in the final costume ball, at which his friends at court dress up as peasant misery, poverty and plague (the ‘disaster ball’). This is then reflected in the final scene, where actual peasants are mowed down in the Regent’s haste to get to Paris to visit a doctor (to tend to his imaginary malaise about his rotting hand). Ever the sole character with a conscience, Orléans gives a young girl some money for having run over her brother. But instead of being grateful, she takes out her rage on his abandoned broken carriage—she predicts more burning as dramatic funereal music (Orléans’ own “O Douleur!” from his opera Penthée) ends the film. No longer a comedy, this film is, in its way, setting the scene well in advance for the French Revolution; indeed, the child-king Louis XV grows up to be very much like his cousin Orléans, enjoying the party but fearing the aftermath, as reflected in his oft-quoted saying, “Après moi le déluge.” Orléans realizes that the party is over, that men like Dubois have unbounded ambitions, and that ultimately France will have to pay.

Bertrand Tavernier, Director, Que la fête commence/Let Joy Reign Supreme, 1975, France, Color, 114 min, Fidebroc, Les Productions de la Guéville, Universal Pictures.

NOTES

- Alexandre Dupilet, La Régence absolue. Philippe d’Orléans et la polysynodie (1715-1718) (Seyssel, Champ Vallon, 2011).

- There is an interesting echo here of Henri de Loraine, 5th Duc de Guise, who sought to make himself ‘king’ of the newly proclaimed Neapolitan republic in 1648, seemingly not comprehending the contradiction. See Sylvana D’Alessio, “Dreaming of the Crown. Political Discourses and Other Sources Relating to the Duke of Guise in Naples (1647–48 and 1654)”, in J. Munns, P. Richards and J. Spangler eds, Aspiration, Representation and Memory. The Guise in Europe, 1506-1688 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), pp. 99-124.