Shannon L. Fogg

Missouri University of Science and Technology

My first introduction to Marguerite Duras’ La Douleur came as an undergraduate studying France and the Second World War in the early 1990s. In a class that used literature and film as a way to approach the history of the Dark Years, Duras’ series of short vignettes served as a window into the life of a woman in the Resistance as she navigated the ambiguity of daily life under the German occupation. First published in 1985 (with Barbara Bray’s English translation appearing the same year as The War), the book has been lauded as “an unforgettable read.”[1] Director Emmanuel Finkiel adapted the first parts of the memoir as a film that appeared in 2018 in France as La Douleur (released in English as Memoir of War). Both the book and the film version provide scholars with valuable tools for examining the war years.

Since that first introduction to The War, I have returned multiple times to the book in the classroom for courses related to war and society. While Duras’s writings can be examined for their literary value, they are also useful for historians.  Duras is often associated with the “nouveau roman” movement of the 1950s in which novelists experimented with new forms to express the ambiguities of the postwar world. Duras’ novels often deal with complex and contradictory emotions, sexuality, the unsaid, and her own past. Born in French Indochina in 1914, she went to France at age 18 to begin her studies in math, political science, and law. She married writer Robert Antelme in 1939 and they lost a child in 1942. In 1943, both she and her husband joined the Rassemblement national des prisonniers de guerre (later: “et déportés”), the Resistance network headed by Mitterand (code name Morland). Antelme was arrested by the Gestapo in Paris on June 1, 1944 and deported to Buchenwald after spending time in both Fresnes prison and the Compiègne concentration camp. As the war entered its final stages, Antelme was marched from the Gandersheim labor subcamp to Dachau, where Mitterand, while on a reconnaissance mission, discovered him in early May, desperately ill, consigned to a quarantined section for hopeless cases. No one was allowed to leave the camp as long as typhus remained rampant. Aware that Robert would not survive if he remained in Dachau, Mitterand organized a rescue mission. On 9 May, disguised as officers, armed with passports, official orders, passes and gas coupons, Dionys Mascolo and Georges Beauchamp dressed him in a uniform, smuggled him out of the camp, and drove him back to Paris.

Duras is often associated with the “nouveau roman” movement of the 1950s in which novelists experimented with new forms to express the ambiguities of the postwar world. Duras’ novels often deal with complex and contradictory emotions, sexuality, the unsaid, and her own past. Born in French Indochina in 1914, she went to France at age 18 to begin her studies in math, political science, and law. She married writer Robert Antelme in 1939 and they lost a child in 1942. In 1943, both she and her husband joined the Rassemblement national des prisonniers de guerre (later: “et déportés”), the Resistance network headed by Mitterand (code name Morland). Antelme was arrested by the Gestapo in Paris on June 1, 1944 and deported to Buchenwald after spending time in both Fresnes prison and the Compiègne concentration camp. As the war entered its final stages, Antelme was marched from the Gandersheim labor subcamp to Dachau, where Mitterand, while on a reconnaissance mission, discovered him in early May, desperately ill, consigned to a quarantined section for hopeless cases. No one was allowed to leave the camp as long as typhus remained rampant. Aware that Robert would not survive if he remained in Dachau, Mitterand organized a rescue mission. On 9 May, disguised as officers, armed with passports, official orders, passes and gas coupons, Dionys Mascolo and Georges Beauchamp dressed him in a uniform, smuggled him out of the camp, and drove him back to Paris.

| Emaciated survivors sit outside a barracks in the newly liberated Dachau concentration camp [camp librerated by American army on 29 April 1945]—US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Frank Manucci, David J. Levy, Kathleen Quinn, Theodore A. Kane Jr. https://www.ushmm.org/learn/timeline-of-events/1942-1945/liberation-of-dachau |

The War contains six stories: “The War;” “Monsieur X, Here Called Pierre Rabier;” “Albert of the Capitals;” “Ter of the Militia;” “The Crushed Nettle;” and “Aurelia Paris.” Duras called the last two stories “invented,” but introduced each of the first four as true stories that recounted her wartime experiences. Duras claimed she found notebooks containing her wartime diary at her home in Neauphle-le-Château but has no memory of having written it. This provides the scholar with an opportunity to explore the overlapping genres of memoirs, novels, and history. [2] This forgetting and remembering are also highlighted in the film version. The War’s first four stories focus on the actions of the French Resistance and the painful wait that many in France endured while their loved ones faced an unknown fate in Nazi hands. These two themes may be the most fruitful in classroom discussions, especially when the book or the film is paired with scholarly, peer-reviewed works on similar topics.

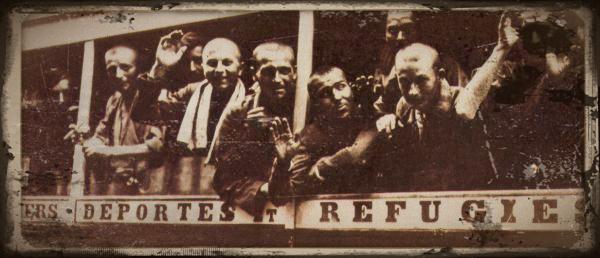

The first story, “The War,” covers the period between Robert Antelme’s arrest and his return and is the major focus of the film adaptation. The story opens in April 1945 with Marguerite waiting for news of Robert to filter back from the liberated camps in Germany. She becomes convinced that he will never return and imagines him dying of cold and starvation in a ditch, or shot by the Germans as they abandon the concentration camps, trying to hide their crimes. She goes to the Gare d’Orsay regularly to gather information from returning prisoners of war and deportees about who was still alive when they left Germany. The last part of “The War” describes in detail Antelme’s debilitated condition after his return, seriously ill with dysentery and fever, the treatments he undergoes, and his slow recovery. While the story is a chronicle of Duras’ daily life, it is also full of references to wartime and Liberation-era events: the military progress of the war, political divisions in France, the deportation of Jews and of workers forcibly and voluntarily recruited for labour in Germany (the STO), the Resistance, and food shortages. Beyond these historical aspects, readers get to feel Marguerite’s emotional and mental state. Her distress is shared by other women who are waiting for their loved ones to return. Duras’s skill as a novelist is to evoke the all-consuming fear and uncertainty that her contemporaries experienced and that is often absent from other wartime memoirs. While some of the “facts” and statistics related to wartime losses are incorrect, they do reflect the state of knowledge for many French men and women (and even the French government) at the time.

http://les-sanglots-longs-des-violons.eklablog.com/retour-des-prisonniers-et-des-deportes-a113961592

“Monsieur X, Here Called Pierre Rabier” also focuses on the period after Robert Antelme’s arrest, beginning just days after he was taken to Fresnes.The stories are thus not presented in chronological order in the collection. This version of Marguerite bears little resemblance to the woman in the first part who confided, “I fall apart, come undone, change” (p. 37) and briefly refers to herself in the third person after collapsing on the floor on hearing the news that Robert was seen alive: “Something gave way at the words saying he was alive two days ago. She offers no resistance. It bursts out through her mouth, her nose, her eyes. It has to come out.” (p. 38) In this second installment, the reader is introduced to Marguerite as a woman who meets regularly with the Gestapo agent who arrested her husband. Duras calls him Pierre Rabier and not by his real name Charles Delval (played by Benoît Magimel). We witness her fear that he will arrest her every time they meet, but we also see her growing confidence as Allied troops approach Paris and she begins to feel free to goad him. The two have a complicated relationship. Duras wants Rabier to give her information about her husband and other captured members of her Resistance network while Rabier tries to glean information about Antelme’s network from her. Marguerite’s status as a novelist dazzles him, or so he insists. At that time, Duras had published her first novel and was working at the Gallimard publishing house. Rabier, who had been masquerading as a Frenchman but was actually German, was arrested on 1 September 1944, tried, sentenced to death, and executed in early 1945. Duras provided testimony both of his cruelty and his lenience.

While these two pieces appear separately in the print version of The War, director Emmanuel Finkiel combines the two into a single narrative. The film begins in April 1945 but soon uses a flashback to integrate the storyline of Robert’s arrest and Marguerite’s subsequent interactions with Rabier. She uses his attraction to her, but is never sure she is not being manipulated instead. The film depicts her ties to the Resistance and her encounters with Rabier. We also witness her affair with her soon-to-be second husband Mascolo (Benjamin Biolay), a close friend of the couple who participated in Antelme’s rescue. In both stories, he appears as D. and is the only person with whom she keeps regularly in touch. With the Liberation, the film shifts back to the seemingly endless wait for Robert and to the narrative of “The War.” It does not, however, include Robert’s recovery and the anguish Duras feels as he hovers between life and death. Thus, in many ways the film is faithful to the story although it would be interesting to compare the film to the memoir as well as to historical sources as part of a class assignment.

Actress Mélanie Thierry captures and seems to embody the fear and the pain that Marguerite Duras hauntingly describes in her book. On screen, Thierry portrays Duras as detached and lonely, even when she is with others. She smokes continuously, refuses food, and fidgets with her fingers while staring vacantly into space. We see the madness induced by months of waiting just to learn if Robert is still alive as the German concentration camps are liberated. In addition Finkiel uses voiceovers to convey some of Duras’s own words and emotions. The viewer hears Marguerite’s internal dialogue that we can read in her “diary.” Some passages in the film are reproduced verbatim from the French text, although Finkiel has clearly used some artistic license, especially regarding her interactions with Rabier.

He also employs visual effects to enhance the intense feelings of worry, loss, and uncertainty portrayed in “The War.” In some scenes, he juxtaposes two Marguerites on screen, emphasizing a kind of psychological split in which Marguerite Duras is able to function on a daily basis, but is also mentally impervious to events.

The questions of memory and forgetting that have often been associated with the Vichy period are clearly present in both versions. Duras introduces “The War” with a strange claim: “I have no recollection of having written it. I know I did, I know it was I who wrote it. I recognize my own handwriting and the details of the story. I can see the place, the Gare d’Orsay, and the various comings and goings. But I can’t see myself writing the diary. When would I have done so, in what year, at what times of day, in what house? I can’t remember” (p. 3). The film shows her writing, but Finkiel also moves back and forth in time, occasionally depicting what Marguerite is imagining.

The film adds a visual dimension lacking from the original memoir. In addition to the cinematography used to emphasize Duras’s emotions, Finkiel recreates Paris under the Occupation. We can see the streets filled with bicycles, posters, and Nazi flags and banners. We go inside the black market restaurants and see the violence against “enemies” of the regime. Marguerite listens regularly to the radio so that we hear Vichy broadcasts. Rooms are often dark and cold and a clock marks the passing of time. As with other adaptations, Finkiel condenses or adds events, but Duras’s major themes of waiting and engagement with the Resistance are present in both the written and film versions.

Throughout “The War,” Marguerite waits for Robert just like other women wait for the return of their POW husbands and still others wait for their deported Jewish relatives. In the classroom I have successfully paired this section of The War with scholarly work focused on POWs. Duras publishes the information she gets from returning prisoners in her newspaper Libres. She interacts with representatives of the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees, and Refugees headed by Henri Frenay. She also visits a neighbor, Madame Bordes, whose despair over not having any news from her POW husband confines her to her bed. Duras emphasizes the shared suffering of these women: “We’re in the vanguard of a nameless battle, a battle without arms or bloodshed or glory; we’re in the vanguard of waiting” (p. 35). Sarah Fishman’s “Waiting for the Captive Sons of France: Prisoner of War Wives, 1940-1945,” or James Quinn’s “Shared Sacrifice and the Return of the French Deportees in 1945” both pair well with The War for discussion or written assignments, allowing students to contextualize Duras’s account within scholarly writings on related topics.[3]

The Resistance, and especially women’s roles in its networks, are emphasized in “The War” and “Monsieur X,” but also appear in “Albert of the Capitals” and “Ter of the Militia,” which are not included in Finkiel’s film. The François Mitterrand connection is clear in both the written and film versions as Rabier shows Marguerite a picture of “Morland,” the leader of her network, and asks if she recognizes him. In the film version, Mitterrand (Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet) is a quietly forceful and empathetic presence who agrees with Marguerite that continuing to meet Rabier would be useful for their network. In post-war interviews, Duras remembered: “’Mitterrand is wonderful. I worked with him in the Resistance. I protected him in the street. We never met in a house or a café. We liked each other so much we could certainly have slept with each other, but it was impossible. You can’t do that on bicycles!’ She laughs.” [4]

Both The War and La Douleur make plain her disdain for Charles de Gaulle, revealing something about postwar politics and the divisions within the Resistance itself despite calls for unity. [5] While her dislike of de Gaulle is peppered throughout both stories, she stated this explicitly in an interview with The New York Times Magazine: “’When de Gaulle arrived in France, I became an anti-Gaullist instantly. I saw through his power game. I saw he was an arriviste, with a special gift for language. And at just that moment they opened the camps, and my husband had been deported. I never got over it, the Jews, Auschwitz. When I die, I’ll think about that, and about who’s forgotten it.’ […] ‘De Gaulle never said a word on the Jews and the camps,’ Yann [her companion at the time] adds quietly. ‘If de Gaulle had not been as big as he was,’ Duras says angrily, ‘no one would have noticed him. Because he was taller than everyone, he was boss. But why this arrogance? As far as I’m concerned, he’s a deserter. He’s horrible, horrible.’”[6] The references to de Gaulle should allow for a discussion of the Gaullist myth that appeared in the early days of the Liberation. [7]

Shorter scholarly pieces on women in the Resistance have worked well with the various sections of The War. I have often used Paula Schwartz “Redefining Resistance: Women’s Activism in Wartime France” with “Monsieur X.” [8] Schwartz’s article argues for an expanded definition of Resistance that includes women’s activities and she describes the type of work that Duras was involved in during the waning days of the war. Schwartz has another article that works well with “Albert of the Capitals” and “Ter of the Militia.” Both of these stories show Duras in a much more active role as she assists in the arrest and torture of informers. Schwartz’s “Partisanes and Gender Politics in Vichy France” focuses on women participating in armed combat and the malleability of gender “tags” during the war. [9]

Using all these sources – memoirs, films, and scholarly pieces – allows students to engage with the war from perspectives that are often overlooked in political histories of the period. We see women actively participating and feel the raw emotions of the time. We can talk about history and memory as well as the gray areas of resistance and collaboration. The memoir and the movie allow us to discuss literature and film, fact and fiction, and love and loss. The War and La Douleur are both accessible for undergraduate students and would allow for a deeper discussion of the many complex and tragic issues associated with France during the Dark Years.

Marguerite Duras, The War: A Memoir, translated by Barbara Bray, New York, The New Press, 1994 (reissue).

Emmanuel Finkiel, La douleuur [Memoir of War], 2017, Color, 127 min, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Cinéfrance 1888, Cinéfrance Plus, Les Films du Poisson, et al.

NOTES

- Marguerite Duras, The War translated by Barbara Bray. Hilary Thayer Hamann, “A Harsh Tale of War, But an Unforgettable Read” https://www.npr.org/2011/06/29/133811002/a-harsh-tale-of-war-but-an-unforgettable-read

- See Liana Vardi’s review that discusses history, fiction, and memoirs, “Truth or fiction and why it matters. A look at Ivan Jablonka, Emmanuel Carrère, and Laurent Binet” Fiction and Film for Scholars of France 7:6 (July 2017). Available at https://h-france.net/fffh/the-buzz/laetitia-ou-la-fin-des-hommes/ . See also Jeanine Parisier Plottel, “Memory, Fiction and History.” L’Esprit Créateur 30:1 (Spring 1990), 47-55.

- Sarah Fishman, “Waiting for the Captive Sons of France: Prisoner of War Wives, 1940-1945,” in Behind the Lines: Gender and the Two World Wars ed. by Margaret Randolph Higonnet et. Al. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987), 182-193. James Quinn, “Shared Sacrifice and the Return of the French Deportees in 1945.” Proceedings of the Western Society for French History Vol. 35 (2007), 277-288.

- Leslie Garis, “The Life and Loves of Marguerite Duras” The New York Times Magazine (October 20, 1991). Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/1991/10/20/magazine/the-life-and-loves-of-marguerite-duras.html

- For a recent and wide-ranging overview of the Resistance, see Robert Gildea, Fighters in the Shadows: A New History of the French Resistance (London: Faber & Faber, 2015).

- Garis, “The Life and Loves of Marguerite Duras.”

- The classic starting point for a discussion on the Gaullist Myth remains Henry Rousso, The Vichy Syndrome: History and Memory in France since 1944 trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press, 1991).

- Paula Schwartz, “Redefining Resistance: Women’s Activism in Wartime France” in Behind the Lines, pp. 141-153.

- Paula Schwartz, “Partisanes and Gender Politics in Vichy France.” French Historical Studies 16:1 (Spring 1989), 126-151.