Charlotte C. Wells

University of Northern Iowa

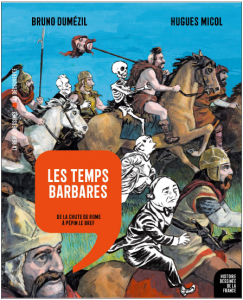

While comic strips (bandes dessinées or BD in French) originated at more-or-less the same time in France and in the United States, they have long since achieved the status of serious and scholarly art in the Francophone world whereas they’ve only recently reached that point in the U.S. [1] Thus no surprise to find that a multi-volume BD Histoire de France (Larousse, 1972-78) appeared forty years ago. Since history, as we all know, changes, there is little cause for astonishment that the BD journal Revue Dessinée is undertaking an update in order “présenter un nouveau visage de l’histoire de France.” [2] Two volumes, La balade nationale and L’enquête gauloise, appeared in 2017. A third Les temps barbares, came out in September 2018. Twenty volumes are planned. The Revue Dessinée operates by pairing experts with graphic artists to produce news commentary that is accurate, visually interesting, and often funny. It follows the same pattern for its historical venture. The results are good on the funny front and very good in terms of visual interest and thoughtful presentations of current knowledge and ideas about the French past.

The first volume, La balade nationale, introduces the series and what it hopes to achieve. Sylvain Venayre, author of the text, is also director of the project. Venayre is professor of modern history at the University of Grenoble. His works focus on travel, French colonialism and the history and art of the bandes dessinées. The illustrator, Etienne Davodeau, is a prize-winning BD artist. Together they have devised an ingenious story line. Several iconic figures from the French past return to help contemporary French citizens understand the texture of their history. They take a road trip (in a mini-van!) around the Hexagon, enlightening and being enlightened along the way. For example, they meet a Syrian refugee who informs them about all the words in French borrowed from Arabic. This historical motley crew includes Jeanne d’Arc, the playwright Molière, the Revolutionary general Alexandre Dumas (“grand-père”), the scientist Marie Curie, and the historian Jules Michelet.

The first volume, La balade nationale, introduces the series and what it hopes to achieve. Sylvain Venayre, author of the text, is also director of the project. Venayre is professor of modern history at the University of Grenoble. His works focus on travel, French colonialism and the history and art of the bandes dessinées. The illustrator, Etienne Davodeau, is a prize-winning BD artist. Together they have devised an ingenious story line. Several iconic figures from the French past return to help contemporary French citizens understand the texture of their history. They take a road trip (in a mini-van!) around the Hexagon, enlightening and being enlightened along the way. For example, they meet a Syrian refugee who informs them about all the words in French borrowed from Arabic. This historical motley crew includes Jeanne d’Arc, the playwright Molière, the Revolutionary general Alexandre Dumas (“grand-père”), the scientist Marie Curie, and the historian Jules Michelet.

Accompanying them, though he refuses to come out of his coffin, is Marshal Pétain. Pétain, who tried to recast the history of France in his own image, even having recourse to BDs for that purpose, is in for a rough ride. [3] As the mini-van makes its way from Carnac to Paris, and to Reims and beyond, Michelet acts as school master and guide to his companions. Each of them, except perhaps Michelet himself, must accept that their beliefs about France and about themselves don’t necessarily conform to the facts. It can be liberating. Jeanne learns that no one really knows what she looked like and proceeds to toss her armor out the van’s window. She doesn’t have to conform to that image any more. On the other hand, the fiery Dumas, already frustrated at being eclipsed by his more famous son and grandson, is distressed to find that his deeds have largely been forgotten and his sole surviving portrait doesn’t look like him at all. The tart-tongued Curie describes what it was like being French and Polish at the same time. Molière provides comic relief and asks the pointed questions that force the others to confront their beliefs. All the while Pétain vociferously resists the truth about himself, even when the group encounters the French Unknown Soldier, who points out that the general’s victory at Verdun was really due to people like him (50).

As it is for the travelers, so too for the country they traverse. As the trip progresses, its purview narrows to the very early history of settlement in what is now France. In spite of Pétain’s protests, the group learns that humanity emigrated to France from Africa, that migration and outside influences have shaped France from the beginning as they shape it now, and that French people come in all colors, faiths, and lifestyles. In short, nothing about France is, or ever has been, as simple as the marshal would have it be. The trip ends with an ingenious twist depositing Pétain back where he came from, while the others vanish back into the mists of time. That is not the end of the book, however. The last quarter of the volume is largely text, with some illustrations. It provides, first, brief biographies of the travelers, revealing that their conversations in the van are often made up of things they actually said. A concise discussion of human evolution and prehistory follows. Last comes an illuminating treatment of the role of images in the teaching of French History and Geography (traditionally taught in the same department).

As it is for the travelers, so too for the country they traverse. As the trip progresses, its purview narrows to the very early history of settlement in what is now France. In spite of Pétain’s protests, the group learns that humanity emigrated to France from Africa, that migration and outside influences have shaped France from the beginning as they shape it now, and that French people come in all colors, faiths, and lifestyles. In short, nothing about France is, or ever has been, as simple as the marshal would have it be. The trip ends with an ingenious twist depositing Pétain back where he came from, while the others vanish back into the mists of time. That is not the end of the book, however. The last quarter of the volume is largely text, with some illustrations. It provides, first, brief biographies of the travelers, revealing that their conversations in the van are often made up of things they actually said. A concise discussion of human evolution and prehistory follows. Last comes an illuminating treatment of the role of images in the teaching of French History and Geography (traditionally taught in the same department).

Venayre points out that the academic pairing of History and Geography really began with the Franco-Prussian war. Believing that their loss came in part from the Germans’ familiarity with French geography, the French education ministry began to see Geography as a way to inculcate patriotism. Patriotism should be focused on the nation as a whole, so touring and books describing tours came into pedagogical favor. And Geography shaped History, as Michelet himself put it (154). The seminal Le Tour de la France par deux enfants (1877) took two boys around the country. They followed the clockwise pattern of the ancient journeyman’s tour (as do the BD travelers of the present volume) with pictures, descriptions and history of each place they stopped. Such iterance contrasted sharply with the sedentary kings of the ancien régime, since it drew the reader’s attention to the whole of the nation (152-153).

The Tour de la France par deux enfants was in the vanguard of illustrated pedagogy in France. The invention of inexpensive ways to insert pictures into school books in the 1830s enabled efforts to “instruire en amusant” (158). Memorable pictures encapsulated History, while text was to define and refine what students saw. Yet at the same time a debate raged over whether illustrations expanded the meaning of text or limited it. Many writers held that illustrations would define the meaning of text that otherwise might be open to varying perceptions and interpretations. Further, the pictures were not always accurate. They often embodied historians’ mistakes, but they made those errors concrete and allowed them to pass into the general understanding of the past. For instance, the winged helmet worn by Astérix le Gaulois in the famous BD isn’t Gallic at all. Historians and archaeologists labelled the Bronze age artifacts as products of the much later culture. But putting the mistake into images (Astérix is by no means the only one) has rooted it so firmly in cultural perceptions that it seems unlikely to go away. So there is peril for History in the use of images. Yet their power to show what is not known, to stimulate contemplation and to play with time and space can bring about a renewal of the “poétique de l’écriture historique” (165). Such is the aim of the Histoire dessinée de la France. This first volume makes a light and lively introduction to the project that leaves the reader eager for more.

The Tour de la France par deux enfants was in the vanguard of illustrated pedagogy in France. The invention of inexpensive ways to insert pictures into school books in the 1830s enabled efforts to “instruire en amusant” (158). Memorable pictures encapsulated History, while text was to define and refine what students saw. Yet at the same time a debate raged over whether illustrations expanded the meaning of text or limited it. Many writers held that illustrations would define the meaning of text that otherwise might be open to varying perceptions and interpretations. Further, the pictures were not always accurate. They often embodied historians’ mistakes, but they made those errors concrete and allowed them to pass into the general understanding of the past. For instance, the winged helmet worn by Astérix le Gaulois in the famous BD isn’t Gallic at all. Historians and archaeologists labelled the Bronze age artifacts as products of the much later culture. But putting the mistake into images (Astérix is by no means the only one) has rooted it so firmly in cultural perceptions that it seems unlikely to go away. So there is peril for History in the use of images. Yet their power to show what is not known, to stimulate contemplation and to play with time and space can bring about a renewal of the “poétique de l’écriture historique” (165). Such is the aim of the Histoire dessinée de la France. This first volume makes a light and lively introduction to the project that leaves the reader eager for more.

Those who move on to the second volume, L’enquête gauloise, will find that its author, Jean-Louis Bruneau, and illustrator, Nicoby, have taken a rather different approach. Venayre and Davodeau appear only briefly (as hitchhikers) at the end of La balade nationale. But Bruneau, an archaeologist and well-published expert on the Gauls, and BD artist Nicoby have made themselves the main characters in their strip. They amble through modern museums and ancient farms as the enthusiastic Bruneau tries to enlighten the not-very-interested artist about the realities of Gallic history. Much of the humor in this volume comes from the interaction between the two. In spite of the different tack, the point remains the same: to replace the myths of French history with what the historical record has revealed. In this context the venerable Astérix le Gaulois comes in for some gentle bashing, another source of humor for those who know that series.

Those who move on to the second volume, L’enquête gauloise, will find that its author, Jean-Louis Bruneau, and illustrator, Nicoby, have taken a rather different approach. Venayre and Davodeau appear only briefly (as hitchhikers) at the end of La balade nationale. But Bruneau, an archaeologist and well-published expert on the Gauls, and BD artist Nicoby have made themselves the main characters in their strip. They amble through modern museums and ancient farms as the enthusiastic Bruneau tries to enlighten the not-very-interested artist about the realities of Gallic history. Much of the humor in this volume comes from the interaction between the two. In spite of the different tack, the point remains the same: to replace the myths of French history with what the historical record has revealed. In this context the venerable Astérix le Gaulois comes in for some gentle bashing, another source of humor for those who know that series.

Bruneau and Nicoby are supported by a cast of actual historical characters: the Roman stateman Cicero being briskly disillusioned of most of his beliefs about the Gauls by his friend, the druid Diviciac, and the source of those beliefs, Julius Caesar himself, encountered at a book signing for his Commentaries on the Gallic Wars. Bruneau’s pointed questions irritate the general, but the historian’s role as heckler-in-chief is quickly taken by Posidonios of Apamea, the Greek scholar from whom Caesar stole most of his non-military information about the Gauls. That argument ends in a fist fight, leaving Cicero and Diviciac to continue the discussion of Gallic civilization in more civilized fashion. They embark on a time-travelling tour that often leaves Cicero disconcerted. They leave pre-Roman Lutetia (Paris) down a modern Metro entrance to travel to the Musée des Antiquités nationales at Saint-Germain-en-Laye. There they view Gallic artifacts, including the tomb furnishings of an excavated warrior. The artifacts spark an astral journey back in time to a Gallic temple and a discussion of Druids’ role in religion and Gallic society. Diviciac, one of the few Druids known to History by name, ought to know. The friends visit temples, settlements, and archaeological sites, sometimes stepping across history, as when Cicero tosses away a strip of metal he’s been fidgeting with, to have it picked up by a modern excavator as a Gallic sword (86). They cross paths with Bruneau and Nicoby, who traverse the same territory in the present day. In spite of all the revelations about the Gauls, Cicero wins the argument, by pointing out that since the Druids kept their secrets by not writing them down, people had to turn to Julius Caesar to find out about Diviciac’s people and their way of life. Diviciac has to admit that an enemy is not the best advocate (142).

Bruneau and Nicoby are supported by a cast of actual historical characters: the Roman stateman Cicero being briskly disillusioned of most of his beliefs about the Gauls by his friend, the druid Diviciac, and the source of those beliefs, Julius Caesar himself, encountered at a book signing for his Commentaries on the Gallic Wars. Bruneau’s pointed questions irritate the general, but the historian’s role as heckler-in-chief is quickly taken by Posidonios of Apamea, the Greek scholar from whom Caesar stole most of his non-military information about the Gauls. That argument ends in a fist fight, leaving Cicero and Diviciac to continue the discussion of Gallic civilization in more civilized fashion. They embark on a time-travelling tour that often leaves Cicero disconcerted. They leave pre-Roman Lutetia (Paris) down a modern Metro entrance to travel to the Musée des Antiquités nationales at Saint-Germain-en-Laye. There they view Gallic artifacts, including the tomb furnishings of an excavated warrior. The artifacts spark an astral journey back in time to a Gallic temple and a discussion of Druids’ role in religion and Gallic society. Diviciac, one of the few Druids known to History by name, ought to know. The friends visit temples, settlements, and archaeological sites, sometimes stepping across history, as when Cicero tosses away a strip of metal he’s been fidgeting with, to have it picked up by a modern excavator as a Gallic sword (86). They cross paths with Bruneau and Nicoby, who traverse the same territory in the present day. In spite of all the revelations about the Gauls, Cicero wins the argument, by pointing out that since the Druids kept their secrets by not writing them down, people had to turn to Julius Caesar to find out about Diviciac’s people and their way of life. Diviciac has to admit that an enemy is not the best advocate (142).

Thus if the first volume raises questions about historical myth and historical reality, the second brings up another big issue: how do we come to understand the history of a culture that left no records? Writing was frowned upon by the Druids, who preferred to pass on their learning orally. As a consequence most of what we know about the Gauls comes either from outsiders, who saw them through the lens of their own different civilizations, or from modern archaeologists, who, Bruneau suggests, are often very good at reconstructing the “what” of the past but not so much at reconstructing the “why.” The Gauls remain mysterious in many ways, although excavations have confirmed much of what ancient authors saw fit to record about daily life.

The accuracy of these ancient authors becomes an even more important consideration when Bruneau and Nicoby climb to the Vercingetorix monument on the site of his great defeat at the battle of Alésia (modern Alise Sainte-Reine in Burgundy) in 52 B.C. While the cartoonist collapses in an exhausted heap, the archaeologist relates the real story of how Caesar took over Gaul and the reader sees events unfold. Turns out the victory was more diplomatic than military and the patriotic hero Vercingetorix was a Roman client who only rebelled when Caesar failed to bestow the rewards he had promised for the Gallic prince’s support. No wonder Vercingetorix didn’t appear in the first volume, even though our historical travelers spent some time looking for him! The chapter, and the book, ends with Nicoby asking plaintively what happened after Alésia and his learned friend replying “But that’s another story.” (164)

The accuracy of these ancient authors becomes an even more important consideration when Bruneau and Nicoby climb to the Vercingetorix monument on the site of his great defeat at the battle of Alésia (modern Alise Sainte-Reine in Burgundy) in 52 B.C. While the cartoonist collapses in an exhausted heap, the archaeologist relates the real story of how Caesar took over Gaul and the reader sees events unfold. Turns out the victory was more diplomatic than military and the patriotic hero Vercingetorix was a Roman client who only rebelled when Caesar failed to bestow the rewards he had promised for the Gallic prince’s support. No wonder Vercingetorix didn’t appear in the first volume, even though our historical travelers spent some time looking for him! The chapter, and the book, ends with Nicoby asking plaintively what happened after Alésia and his learned friend replying “But that’s another story.” (164)

L’enquête gauloise is at first a harder read than La balade nationale. Rather than placing the BD first and the straight text behind, Bruneau and Nicoby have chosen to intersperse them. The reader begins by skimming impatiently through discussions of Gallic material culture, looking for a return to the comics, but as the dialogue between BD and text develops, slowing down becomes imperative so as not to miss the connections. In the end a good deal of learning happens, and quite pleasantly too.

L’enquête gauloise is at first a harder read than La balade nationale. Rather than placing the BD first and the straight text behind, Bruneau and Nicoby have chosen to intersperse them. The reader begins by skimming impatiently through discussions of Gallic material culture, looking for a return to the comics, but as the dialogue between BD and text develops, slowing down becomes imperative so as not to miss the connections. In the end a good deal of learning happens, and quite pleasantly too.

This interesting endeavor is off to a good start. It ought to find a wide general readership in the Francophone world and certainly could be considered for advanced French language classes in Anglophone colleges and universities. Until a translation makes it more generally accessible, the reader confined to English may want to investigate Larry Gonnick’s Cartoon History of the Universe and Cartoon History of the Modern World. Lacking a scholarly partner, Mr. Gonnick chose to tell tales rather than attempt analysis, but he got his stories from primary sources and he tells them with verve and panache. The volumes of the BD Histoire de France will sit on this reviewer’s bookshelf alongside his. I may need to get a larger bookshelf: I’ve already ordered volume 4.

PS: Vol. 4 (volume 3 has not yet been published) arrived too late to review, but it’s the best so far. Thoughtful — and hilarious! The series is moving on from how moderns make up the past to how people in the past made up the past, featuring Gregory of Tours as movie director! I am definitely hooked.

PS: Vol. 4 (volume 3 has not yet been published) arrived too late to review, but it’s the best so far. Thoughtful — and hilarious! The series is moving on from how moderns make up the past to how people in the past made up the past, featuring Gregory of Tours as movie director! I am definitely hooked.

Sylvain Venayre and Etienne Davodeau. La Balade nationale. Paris: Revue Desinée/Éditions La Decouverte, 2017.

Jean-Louis Bruneau and Nicoby, L’Enquête gauloise. Paris: Revue Desinée/Éditions La Decouverte, 2017.

NOTES

- The acceptance of American comics as literary art was signaled by the award of a Pulitzer Prize to Art Spiegelman’s Maus (New York: Pantheon Books, 1991) in 1992.

- “L’Histoire de France comme vous ne l’avez jamais vue.” http://editionsladecouverte.fr/Histoiredessineedelafrance. Accessed August 20, 2018. Éditions la Découverte is partnering with Revue Desinée on this project.

- Joel E. Vessals, Drawing France: French Comics and the Republic (Oxford: University of Mississppi, 2010), ch. 3, “Notre Grand-Papa Pétain: The National Revolution and Bande Dessinée in Vichy.” http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/rodlibrary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=538C045. Accessed July 20, 2018