Ruth Schwertfeger

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Emerita

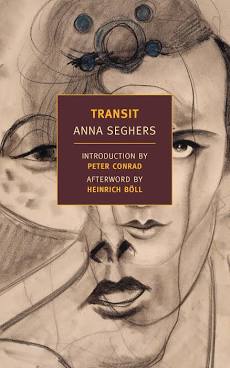

Transit, the title of German director Christian Petzold’s recently released film is based on the novel with the same title written by Anna Seghers during her exile in France. On a narrative level, ‘transit’ is a prime metaphor for the fate of all Germans who had fled from the Third Reich, but especially for German Jews who, in France, found themselves doubly stigmatized as both Germans—the despised boches–and then as juifs, not israélites, the preferred term for French-born Jews. The years of darkness, however, had already begun in the mid-thirties for thousands of Germans, a long time before the French coined the term “les années noires.” German Jews were among the estimated 76,000 Jews, two thirds of them foreign born, who were deported to the camps of the east from France, where they perished. Unlike many others, Seghers was able to leave France before the major deportations, along with her two children and her husband, who had been interned in Le Vernet. Seghers had first-hand knowledge of the trials of refugees, many at the hands of petty clerks. At least one writer—Hilde Eisler—mentions seeing Seghers in Marseilles in a café on the Cours Belsunce, quietly writing in a notebook: “I admired very much that in such an improvised existence, in an atmosphere of chaos and nervousness she exuded a tremendous sense of peace.”[1] Seghers continued to work on the novel during the course of their long and arduous journey that started in March 1941, when they finally received the necessary visas to leave France. Refugee life in occupied France is the backdrop for both the novel and its cinematic adaptation.

Un bateau de réfugiés en juin 1940. © Getty / Collection Hulton-Deutsch / CORBIS: Exils avec Adrien Bosc et Patrick Straumann, France Inter

Although Christian Petzold has divested the original story of visible connections to Occupied France (swastikas, Nazi uniforms etc.), he does not flinch from presenting starving refugees waiting for visas to leave a country, described in the words of Seghers’ narrator as “shattered and defiled.”[2] He also presents harrowing scenes of raids–the infamous rafles that usually took place in the middle of the night in seedy hotels in Marseilles near the harbor. The most dramatic aspect of Petzold’s adaptation, however, is the insertion of another narrative that reaches beyond occupied France into the context of contemporary France. His camera focuses on North African immigrants, living in arguably more straitened circumstances than the refugees from Nazi Germany. He captures their frightened gaze in brief shots that convey the emotional toll on their lives as they eke out a precarious existence in today’s Marseilles. They live in overcrowded, shabby housing with a décor that has barely changed since foreign-born refugees found shelter in the same rooms in the forties. The two worlds thus blend and intersect on the shared ground of the port city of Marseilles; both communities live on the edges of French life, separated in years by an average life span but joined by the common fear of deportation. Petzold captures and sustains this Kafkaesque terror with leitmotifs that underscore their endangered and transitory status–wailing police sirens of today’s noisy world, the ever-swinging doors of cafés of the early forties which open and close to reveal refugees huddled together over cheap wine and inadequate food.

What connects and separates the novel to and from the film? Seghers is less absorbed with evoking the ethos of displacement than she is with narrating a story, line by line, point by point, with the stolid resolve of a modern-day Ancient Mariner. The narrator does not move from the table in the harbor café where the unnamed listener also remains seated. Seghers leads the reader on a journey that is in constant motion, and consummately constructs and controls the commentary. In the end, we are left suspended, with a manuscript that has no ending. She has penetrated the bureaucratic nightmare that ruled consulates and government offices in Occupied France, the surrealistic world of refugee life, the administrative chicanery, the anguish of waiting rooms, the anxiety about a visa, a permit to travel, an exit visa, a residence visa, a transit visa, safe conduct visas, exit stamps from internment camps etc. The search for valid documents became the sole focus of refugees, their obsession and raison d’être. It involved endless visits to consulates and was their only topic of conversation. The cast of characters includes both Jews and non-Jews, both partisans and the politically indifferent, prestataires and legionnaires. Peztold’s camera largely respects the same nightmare preoccupation.

A summary of the novel will help identify the major points of convergence and divergence with the film. The novel begins with the rumor that has reached Marseilles that the Montreal, a ship carrying refugees, has just sunk. Seghers places the story in the mouth of a German-born, former small-tools mechanic who forewarns his listener that he is going to tell his story in sequence, just as it happened. Like him, we too are forced to listen. Despite his detached manner, the narrator appears to have a deep connection to the Montreal, one that the reader has difficulty in deciphering, even though the characters are recognizable types among refugees of the period. We only know that the narrator is a political refugee who escaped from a German prison camp to France by swimming across the Rhine. After yet another imprisonment in France, he escaped again from a camp near Rouen, along with several Germans, one called Heinz who had lost a leg fighting in the Spanish Civil War, a writer called Paul Strobel, and a dramatist. They all meet up again in Paris soon after their escape but after the fall of Paris they take separate routes out of the now occupied city to make their way to the south. The two writers, we later learn, had the financial resources to make that journey in relative comfort.

Their destination is Marseilles, the logical place for anyone wanting to leave France in 1940, and it is there that the narrator meets two other characters who become central players in his story, both Germans, one a Jewish doctor, in love with a German woman who is waiting for her exit visa in Marseilles. Her story emerges slowly, in the same deliberately slow cadence of the narration. The woman’s name is Marie, and she is the estranged wife of a German Jewish writer whom she fully expects to catch up with her in Marseilles, as he is in possession of visas for both of them. Although she no longer wants to be his wife, she will not be able to leave without the visa he has in his possession. Their survival and individual destiny, although no longer together, is dependent on a visa.

The narrator sets the intricate plot in motion in Paris, when he sets off to deliver a letter to a writer called Weidel. He had run into Paul Strobel in the street, in a state of panic to get to the Free Zone. Seghers has the narrator make the following (one suspects discerning) remark about Strobel: “He couldn’t bring himself to believe that he was not the same poor devil as I was…He was firmly convinced that the Gestapo had nothing else to do but wait in front of this man Weidel for little Paul.”[3] Seghers thus touches on a fundamental aspect of German refugee status. At a certain level, they were all under threat yet each one, especially the prominent intellectuals, was convinced that he/she was the most threatened. The narrator proceeds to seek out the hotel in Paris where Weidel had last lived, only to learn that the latter has committed suicide in his hotel room—to the outrage of the Frenchwoman who manages the hotel and who is only too glad to dispose of the dead man’s belongings. These consist of a manuscript, two letters of rejection—one from Weidel’s wife, ending their marriage, and a letter of rejection from a publisher–and an official letter from the Mexican consulate, informing him that a visa and money are waiting for him in Marseilles. The contents of the case define what his life has been reduced to—rejection on two levels, but also hope, in the form of a promised visa. Curious, the narrator begins to read the manuscript: “I had lived my life to the full but had not read. So this was all new to me. And my I read! In this story there was, as I have said, a heap of crazy people, a really mixed-up bunch…Then suddenly, about on the thirty-third page, everything stopped for me. I never learned how it ended. The Germans had arrived in Paris, the man had packed up everything, his few bits and pieces, his writing paper. And left me on my own right in front of the last page that was almost empty.”[4] He grieves the loss of this unknown writer whom he would have convinced to keep on living. “I would have found a hiding place for him. I would have brought him food and drink.” Seghers thus allows the narrator to become totally involved and identified with the life depicted in the manuscript.

After he reaches Marseilles, he himself assumes the life of a refugee, adopting the brand new and coveted identity of a dead Saarlander, an identity that is not without significance for both the story and the period, poised as Saarland was between France and Germany, and having made the choice in a plebiscite of 1936 to be annexed to the Reich rather than stay with France. His new identity gives him the right to receive hand-outs from various committees that pay for a tiny room in a hotel in the harbor district that is also the quarters for refugees attempting to leave Marseilles. He makes a somewhat feeble effort to give Weidel’s small case that contains the manuscript to an official at the Mexican consulate but the name on his identity card—Seidler—is presumed by the consular official to be the pseudonym of the dead Weidel, whose wife is meanwhile frantically looking for him. So, the narrator spends his days shuffling from café to café, consulate to consulate, with two identities—a Saarlander, and a German Jewish writer, both dead. We never find out his true identity.

After he reaches Marseilles, he himself assumes the life of a refugee, adopting the brand new and coveted identity of a dead Saarlander, an identity that is not without significance for both the story and the period, poised as Saarland was between France and Germany, and having made the choice in a plebiscite of 1936 to be annexed to the Reich rather than stay with France. His new identity gives him the right to receive hand-outs from various committees that pay for a tiny room in a hotel in the harbor district that is also the quarters for refugees attempting to leave Marseilles. He makes a somewhat feeble effort to give Weidel’s small case that contains the manuscript to an official at the Mexican consulate but the name on his identity card—Seidler—is presumed by the consular official to be the pseudonym of the dead Weidel, whose wife is meanwhile frantically looking for him. So, the narrator spends his days shuffling from café to café, consulate to consulate, with two identities—a Saarlander, and a German Jewish writer, both dead. We never find out his true identity.

In the course of long hours in local cafés, the narrator becomes obsessed with the sight of an attractive woman who is apparently looking for someone. He shadows her, waits for her, finally connects with her, only to find out that the mysterious woman is Marie, the wife of Weidel, the object of her futile search. The narrator begins to project upon the dead man’s wife an obsessive attachment that develops into a shadowy, insubstantial relationship. Technically, his identity as Weidel has given him the right to be her husband and claim the visas that are in the case, but the presence of the German-Jewish doctor stands in their way, and the relationship is not consummated.

The genius of Transit as a novel lies in a depiction of the early days of Occupied France that is inhabited by credible characters attempting to survive in a world that has lost all sense of what is normal. They have not emerged from the mythology of a noble France or German Resistance, but as ‘poor devils’ like the pompous writer Strobel, or the narrator himself, who is apathetic most of the time. He fails to keep appointments, even with the person he truly admires, his fellow resister Heinz to whom he confesses that his life is falling apart.[5] He tries to tell Marie Weidel that her husband has committed suicide, but he does not insist on the veracity of his statement, with the result she does not believe him. She too is left suspended and continues to think that her husband is really in Marseilles, and has already picked up his visa, just as the consul had told her. For the consul also thinks that Seidler is Weidel. The narrator in the end makes a choice that some may erroneously connect to Casablanca. He does not leave with the wife of a dead German Jewish writer or entice her into staying with him. Instead he chooses to work on a farm near Marseilles, with members of the Resistance who are fighting the occupiers—former Spanish republicans now fighting against Nazism. At the end, the French activist Georges Binnet tells him: “You belong to us. Whatever happens to us happens to you.”[6]

The silent but ubiquitous presence in Transit is the Jewish writer who was driven by terror of the advancing German army to suicide, in a city which he thought would provide refuge.  Early on in his film version, Christian Petzold introduces us to the writer in a dramatic shot of a dead body covered in blood, draped over the edge of a bathtub in a shabby hotel in Paris. Whether or not the visual reference to Roland Barthes’ “The Death of the Author,” is willful on Petzold’s part, it suggests an irresistible commentary on the post-modern theory of not assigning ultimate meaning to a text. Petzold’s depiction of a brutally violent suicide is far removed from the gentler death that several refugees chose; they had the necessary pills (like Walter Benjamin) should they be driven to take their own lives. As already noted, Petzold has also folded in contemporary social issues that, although set in present-day France, are also pressing global issues. In the process, he has divested the original story of its historical specificity and collapsed key phases of the Occupation to suit his storyline.

Early on in his film version, Christian Petzold introduces us to the writer in a dramatic shot of a dead body covered in blood, draped over the edge of a bathtub in a shabby hotel in Paris. Whether or not the visual reference to Roland Barthes’ “The Death of the Author,” is willful on Petzold’s part, it suggests an irresistible commentary on the post-modern theory of not assigning ultimate meaning to a text. Petzold’s depiction of a brutally violent suicide is far removed from the gentler death that several refugees chose; they had the necessary pills (like Walter Benjamin) should they be driven to take their own lives. As already noted, Petzold has also folded in contemporary social issues that, although set in present-day France, are also pressing global issues. In the process, he has divested the original story of its historical specificity and collapsed key phases of the Occupation to suit his storyline.

But there are also moments in the film that reveal a deep respect for Seghers’ understanding of the loss of native language in exile. In a pivotal scene in the film, Georg (named in this version) wins the heart of Driss, an immigrant child by repairing his radio. Together they listen to a haunting German lullaby that Georg’s mother used to sing to him. The North African Melissa, Driss’s deaf mother, is transfixed and signs to her boy to make Georg sing it again. In a sense, the scene functions as a metaphor for key choices of divestment that he has made as film director. In this case, Petzold is asking us to look at what we are not able–or allowed–to hear. He carefully controls the language of the occupier. At key moments in the film, we are allowed to hear the comforting, slow intonation of the German text, but in this scene German has been transposed into another key. At other moments, he reduces German to snippets, as in one exchange with Driss, who knows a German swear word and the name of a German soccer team.

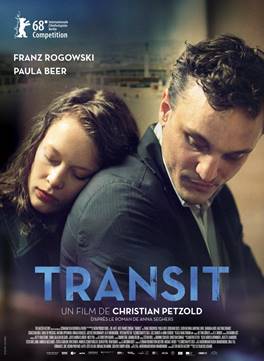

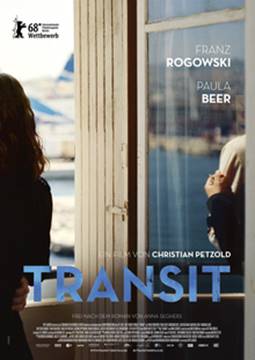

The convergence of novel and film meet in the choice of Franz Rogowski who has to play the part of both the dissident Georg (with an assumed German-Jewish identity) as well as a young German male with modern sensibilities. Rogowski projects an appropriate dissonance and disharmony that are visually arresting–the slightly battered albeit handsome face is strangely at odds with his athletic body.  His dexterity in soldering tiny parts of a broken radio together (he must have learned the trade of Feinmechaniker at home in Nazi Germany) is performed with the same hands that embrace a fatherless immigrant boy and show him how to handle a soccer ball and defend in a makeshift goalpost. As already noted, this scene also conveys an unexpected facet of a lost homeland. Petzold goes off script and appeals to our ear and not our eye. For a brief moment, we are allowed to hear the sounds of home, in a children’s song that evokes the loss of both a mother and a mother tongue. By joining together broken parts, Peztold produces the hauntingly mellifluous tones of German that invites the listener—and one suspects, the director–to come home. It is a rare moment in a film that otherwise insists on the visual. It also unites us to the original text when the narrator reads directly from the Seghers’ manuscript, and we again enter its familiar tempo, sheltered from the throbbing pulse of modern life.

His dexterity in soldering tiny parts of a broken radio together (he must have learned the trade of Feinmechaniker at home in Nazi Germany) is performed with the same hands that embrace a fatherless immigrant boy and show him how to handle a soccer ball and defend in a makeshift goalpost. As already noted, this scene also conveys an unexpected facet of a lost homeland. Petzold goes off script and appeals to our ear and not our eye. For a brief moment, we are allowed to hear the sounds of home, in a children’s song that evokes the loss of both a mother and a mother tongue. By joining together broken parts, Peztold produces the hauntingly mellifluous tones of German that invites the listener—and one suspects, the director–to come home. It is a rare moment in a film that otherwise insists on the visual. It also unites us to the original text when the narrator reads directly from the Seghers’ manuscript, and we again enter its familiar tempo, sheltered from the throbbing pulse of modern life.

A central character in the film (borrowed from the novel) is Heinz, one of the few fellow exiles admired and respected by Georg because of consistent loyalty to his socialist ideology—despite having lost a leg in the Spanish Civil War. He does not survive for long in Petzold’s world and, in fact, dies in the freight train en route to Marseilles, sacrificed in the interests of the storyline as the dead father of little Driss (which is why Georg goes looking for the boy and his mother). Why is this significant? In the novel, he is the one figure who is unambiguously committed to resistance and the man who has won Georg’s respect. In the end, Georg will leave Marseilles and join fellow resisters. The film implies that he will head for the Spanish border to hike to freedom across the Pyrenees to Portugal. The oblique reference to the Pyrenees conjures up a list of German notables, like Walter Benjamin, Franz Werfel, Lion Feuchtwanger and Heinrich Mann, most of whom made it safely over the mountains to Lisbon to board overseas liners while others, like Benjamin, did not. This is arguably the most serious rupture of Transit’s political meaning. As flawed a character as Georg is, he did not survive the prisons and camps of the Third Reich and swim across the Rhine to simply escape from the occupiers and blend into the exiting stream of well-heeled intellectuals. In Seghers’ world, he will stay and fight, whereas Weidel’s wife will leave with the doctor. Paula Beer’s role as Marie is just as effective as Rogowski’s because she succeeds in projecting complexity and credibility. Beer liberates Marie from the perception that she an abstraction, flitting around the streets of Marseilles in high heels in search of her husband. In fact, she is ambiguous about where and to whom she belongs. Beer’s nuanced performance exudes both vulnerability and sensuality that rescue the film from the fallacy that it is a love story in the mode of Casablanca. Although there is a level of physical and emotional intimacy between her and Georg, it is never consummated and like the story, remains suspended. The only real love story in both the novel and the film is the fraternal affection between a German refugee and a little immigrant boy.

What might Seghers have thought of this film adaptation? Given her reputation as one of the least self-absorbed in a generation of writers who were not overly encumbered by altruism, one would suspect that she would have welcomed the adaptation, and especially Petzold’s engagement with social issues. But she might have also asked him some penetrating questions about his choices. After all, she was no novice in visual art. Her eye had been trained as an art historian on the tableaux of Rembrandt while preparing for her doctoral dissertation. She might very well have alerted Christian Petzold to the presence of deeper shadows that he could have included.

Anna Seghers, Transit, Transit, translated from the German by James A. Galston, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1944.

Christian Petzold, Director, Transit, Germany, France, 2018, Color, 101 min, Schramm Fil, Neon Productions, Arte France Cinéma, ZDF/Arte.

NOTES

- Cited by Hans-Albert Walter, Exilliteratur 1933-1950, Volume 7, Stuttgart: B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 421.

- Transit, translated from the German by James A. Galston, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1944.

- Transit, 118.

- Ibid.

- Transit, 119.

- Transit, 310.