Kristen Stromberg Childers

Eastern University

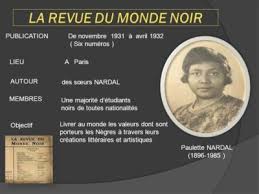

Aimé Césaire’s Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land) is one of the foundational texts of Négritude, the literary affirmation of black identity, history, and culture in response to historical French racism and colonialism. In the interwar years, Césaire, along with fellow students Léopold Sédar Senghor from Senegal and Léon Gontran Damas from Guyane, convened in the Paris home of the Nardal sisters from Martinique where they discussed their status as “uncivilized” colonial subjects, straddling the worlds of metropolitan France and the African diaspora. The Cahier first appeared in 1939 but was revised through the years, with Césaire making significant changes to subsequent editions in 1947 and 1956. In the mid-twentieth century as Europe endured the spasms of fascism, war, and decolonization, Césaire’s Cahier was a revolutionary call to pride in black identity amidst the degradations of imperialism and the self-alienation of colonized peoples.

Aimé Césaire is one of the most famous Antilleans, people of the French Caribbean, who defied the currents of decolonization in the post-World War II era and voted in 1946 to become completely French, transforming the islands into regular administrative “departments” (Départements d’outre mer, hereafter DOMs) of the French nation rather than independent states or colonies. Despite the fact that they were thousands of miles away, Martinicans and Guadeloupeans were proclaimed fully French citizens, and administrators of the Fourth (1946–1958) and Fifth Republics (1958–) launched a variety of social, cultural, and economic projects to integrate them into the French “family.” Proposed by the Communist Deputies of Martinique, Aimé Césaire and Léopold Bissol, along with the deputies from Guadeloupe, Réunion, and Guyane, departmentalization was put forward as the culmination of a long process of assimilation that had been sought by Antilleans since the eighteenth century. By joining the metropole, continental France, the people of Martinique and Guadeloupe hoped they were on their way to making their islands into the Promised Land. Aimé Césaire was an eloquent champion of departmentalization in 1946; by 1949, however, he was disillusioned with the promises of the so-called assimilation law and declared it a “caricature” and “parody” of what Antilleans had asked for.[1]

Part of the impetus behind departmentalization was the long history of France’s ties with the vieilles colonies, but it was also generated by the racist and reactionary treatment Antilleans suffered at the hands of the Vichy-backed regime that took over after France’s defeat in 1940. Seen as a haven both for gold bullion from the Bank of France and for those labeled dangerous “agitators” in metropolitan France, Martinican society was strained by the attitudes of many white French sailors who had fled with the French fleet. The surrealist poet and artist André Breton was one of those refugees who made his way to the Caribbean after he was arrested and harassed by Vichy officials in the early days of the war.

In March 1941, he obtained a visa for the United States and left Marseilles via Martinique along with his wife and daughter. Other notable passengers on the ship included Claude Lévi-Strauss, who described how he and Breton were regularly referred to as “scum” by the gendarmes onboard the ship. What awaited Breton in Fort-de-France was even worse—he and other “undesirables” were sent to Lazaret prison, a former leper colony, where food was nonexistent and the sleeping arrangements made them wish they were back on the filthy boat. Breton was finally granted leave from the prison at Lazaret and was free, albeit under constant government surveillance, to wander the streets of Fort-de-France while he awaited the next leg of his journey to New York.[2] During these wanderings in his brief three-week stopover in Martinique, he made a fortuitous discovery. Seeking to buy ribbon for his daughter, he wandered into a local shop and came across a pamphlet:

In March 1941, he obtained a visa for the United States and left Marseilles via Martinique along with his wife and daughter. Other notable passengers on the ship included Claude Lévi-Strauss, who described how he and Breton were regularly referred to as “scum” by the gendarmes onboard the ship. What awaited Breton in Fort-de-France was even worse—he and other “undesirables” were sent to Lazaret prison, a former leper colony, where food was nonexistent and the sleeping arrangements made them wish they were back on the filthy boat. Breton was finally granted leave from the prison at Lazaret and was free, albeit under constant government surveillance, to wander the streets of Fort-de-France while he awaited the next leg of his journey to New York.[2] During these wanderings in his brief three-week stopover in Martinique, he made a fortuitous discovery. Seeking to buy ribbon for his daughter, he wandered into a local shop and came across a pamphlet:

Between modest covers was the first issue of a magazine called Tropiques, just off the press in Fort-de-France. It’s unnecessary to mention, knowing how far downhill things have gone in the last year in corruption of ideas and having personally experienced the absence of all subtlety that characterizes police actions in Martinique, I opened this volume with extreme suspicion… I could not believe my eyes: what was said was just what needed to be said, not only well, but as forcefully as one could say it! All those grimacing shadows were shredded and dispersed; all those lies, those sneers fell away in tatters: The human voice was not stifled and broken after all; it rose here like the very staff of light. Aimé Césaire was the name of the one who spoke.[3]

The shopkeeper was the sister of René Ménil, who, along with Aimé and Suzanne Césaire and Georges Gratiant, was the intellectual force behind the journal Tropiques. Starting in April 1941, this group of artists and writers had begun to publish the journal, which focused on the culture, folklore, and history of the Antilles.  Through this chance encounter, Breton was able to meet Suzanne and Aimé Césaire and many of their friends, who engaged him in lively conversation, showed him around the island, and restored his faith in the possibilities of artistic creation in these somber years.

Through this chance encounter, Breton was able to meet Suzanne and Aimé Césaire and many of their friends, who engaged him in lively conversation, showed him around the island, and restored his faith in the possibilities of artistic creation in these somber years.  The Césaires, who were both teachers at the Lycée Schoelcher, were also energized by their meetings with Breton, for the encounters helped to break the isolation of their existence in Martinique and brought the Tropiques group into contact with a much wider international audience. Tropiques became increasingly bold in its attacks on the Vichy regime, and censors finally shut it down in May 1943. In his letter to Césaire, Lt. de Vaisseau Bayle, the chief of the Service d’Information, wrote that while he had no reservations about allowing a cultural and literary revue to be published, he did object to a journal that was “revolutionary, racist and sectarian” and would “poison spirits, sow hatred and ruin morality.” Bayle went on to say that the manuscripts submitted to him for an upcoming issue of Tropiques were particularly disturbing given that Césaire was a well-paid employee of the state. It was shocking to see someone “who had achieved a high level of culture and a place at the highest ranks of society attempting to call for revolution against a homeland that had been for them such a generous country.” The director of censorship wanted to remind him that he was, after all, a Frenchman.[4] Picking up on this cue, the editors of Tropiques responded that they were not bothered by these accusations at all:

The Césaires, who were both teachers at the Lycée Schoelcher, were also energized by their meetings with Breton, for the encounters helped to break the isolation of their existence in Martinique and brought the Tropiques group into contact with a much wider international audience. Tropiques became increasingly bold in its attacks on the Vichy regime, and censors finally shut it down in May 1943. In his letter to Césaire, Lt. de Vaisseau Bayle, the chief of the Service d’Information, wrote that while he had no reservations about allowing a cultural and literary revue to be published, he did object to a journal that was “revolutionary, racist and sectarian” and would “poison spirits, sow hatred and ruin morality.” Bayle went on to say that the manuscripts submitted to him for an upcoming issue of Tropiques were particularly disturbing given that Césaire was a well-paid employee of the state. It was shocking to see someone “who had achieved a high level of culture and a place at the highest ranks of society attempting to call for revolution against a homeland that had been for them such a generous country.” The director of censorship wanted to remind him that he was, after all, a Frenchman.[4] Picking up on this cue, the editors of Tropiques responded that they were not bothered by these accusations at all:

“Poisoners of the spirit,” like Racine, according to the Lords of Port-Royal; “Ungrateful traitors to our generous country” like Zola, according to the reactionary press; “Revolutionary” like Hugo in Châtiments; “Sectarian,” with passion like Rimbaud and Lautréamont; “Racist,” yes. Racist like Toussaint Louverture, Claude Mac Kay and Langston Hughes—but not like Drumont and Hitler.”[5] This short-lived journal, published in conditions of penury during the war, not only impressed the visiting Breton but went on to have a powerful impact on raising the consciousness of an entire generation of students and intellectuals, both in the Antilles and in metropolitan France.

“Poisoners of the spirit,” like Racine, according to the Lords of Port-Royal; “Ungrateful traitors to our generous country” like Zola, according to the reactionary press; “Revolutionary” like Hugo in Châtiments; “Sectarian,” with passion like Rimbaud and Lautréamont; “Racist,” yes. Racist like Toussaint Louverture, Claude Mac Kay and Langston Hughes—but not like Drumont and Hitler.”[5] This short-lived journal, published in conditions of penury during the war, not only impressed the visiting Breton but went on to have a powerful impact on raising the consciousness of an entire generation of students and intellectuals, both in the Antilles and in metropolitan France.

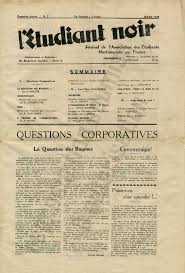

Aimé Césaire had already achieved a certain literary prominence before the war, publishing in various journals in France like L’Etudiant Noir, and in his Cahier d’un retour au pays natal, which first appeared in 1939. Notebook of a Return to the Native Land is a long poem written on the eve of Césaire’s departure from France before World War II. He had failed his agrégation exams and was transitioning between worlds, both figuratively and geographically. As one of the évolués, intellectuals from throughout the French empire who were trained in classical French education in the metropole and expected to assimilate to European culture, Césaire found himself rebelling against these expectations and yet estranged from his own identity as a man from, and returning to, Martinique. The Cahier’s narrative arc consists of three main parts: At the beginning, a first-person narrator contemplates his island home and especially its many flaws:

At the end of daybreak burgeoning with frail coves, the hungry Antilles, the Antilles pitted with smallpox, the Antilles dynamited by alcohol, stranded in the mud of this bay, in the dust of this town sinisterly stranded.[6]

The “I” of the poem, understandably interpreted as Césaire writing autobiographically, then reflects on his identity and alienation from his own roots, whether they be in the Antilles or in Africa. The tone is morbid and suffocating, the only glimpse of levity appearing in reference to a celebration of Christmas and good food shared with family. Throughout the Notebook, Césaire intersperses jarring metaphors and surrealistic images in the poem, such as “but can one kill Remorse, perfect as the stupefied face of an English lady discovering a Hottentot skull in her soup tureen?”[7] The narrator next links his own degradation and the enslavement of his people to the plight of blacks throughout the African diaspora, shipped as cargo from the slave ports of Nantes and Bordeaux to the other side of the Atlantic, whether in Georgia, Alabama, or Saint Domingue. He identifies with the leader of the revolution in Haiti, imprisoned in a cold cell in the Jura:

a lone man imprisoned in whiteness

a lone man defying the white screams of white death

(TOUSSAINT, TOUSSAINT LOUVERTURE)[8]

As the narrator reflects on his return to his native land, he leaves Europe, “utterly twisted with screams, the silent currents of despair, leaving timid Europe which collects and proudly overrates itself.”[9] He begins to summon his memories and his sense of self, yet berates himself by admitting his own judgment and repulsion at seeing a “comical and ugly nigger” on a streetcar in France.[10]

Here, the poem takes a final turn to a new sense of identity, grounded in a valorization rather than a demonization of all that is black. “But what strange pride suddenly illuminates me?” he asks, going on to describe his negritude in opposition to all the negatives that have been ascribed to blackness before.[11] The narrator finds dignity in his ancestry and summons the power to return to his homeland triumphant, rooted, and full of promise.

One of the first complications to consider when teaching the Cahier is that there are in fact four different iterations of the poem, with the first version of 1939 markedly different from the version until recently considered “definitive,” published in 1956 by Présence Africaine. The differences emerge from the very beginning, as the 1956 version begins with the directly confrontational stanza: “Beat it, I said to him, you cop, you lousy pig, beat it, I detest the flunkies of order and the cockchafers of hope. Beat it, evil grigri, you bedbug of a petty monk.”[12] These opening lines are entirely absent from the 1939 version, which has a decidedly less antagonistic character. This qualitative change has complicated the literary criticism surrounding Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, with some scholars decrying the more political tone of the final version.[13] Published around the time of Césaire’s renunciation of the Communist party, the last Cahier included new verses and themes that either brought out nascent ideological notes present in the original or clumsily superimposed politics onto the literary genius of the original, according to differing critics.[14]

Césaire’s standing as a major figure of French literature in the 20th century would make the Cahier essential reading in modern European or post-colonial literature courses, where the implications of artistic choices and the text’s change over time could be fruitfully discussed.  The surrealist nature of the poem and André Breton’s serendipitous discovery of Césaire’s work during his passage through Martinique can be understood in partnership with the Harlem Renaissance and Black Atlantic networks in the interwar years and beyond. Certainly as one of the first and most important texts describing the concept of Negritude, the Cahier can be read as the 20th century’s response to the colonialism of the 19th century. In Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, another text inscribing misery and despair directly onto the physical landscape, the Africans along the Congo river are silent and without names or language. In Césaire’s Cahier they have found their voices, and can take pride in the fact that their ancestors are “those who explored neither the seas nor the sky, but who know in its most minute corners the land of suffering, those who have known voyages only through uprootings.”[15] The Cahier serves to demonstrate the power inherent in claiming an identity and a color that has been maligned and persecuted in European culture and totally transforming it into an affirmative force to be reckoned with in the post-colonial age.

The surrealist nature of the poem and André Breton’s serendipitous discovery of Césaire’s work during his passage through Martinique can be understood in partnership with the Harlem Renaissance and Black Atlantic networks in the interwar years and beyond. Certainly as one of the first and most important texts describing the concept of Negritude, the Cahier can be read as the 20th century’s response to the colonialism of the 19th century. In Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, another text inscribing misery and despair directly onto the physical landscape, the Africans along the Congo river are silent and without names or language. In Césaire’s Cahier they have found their voices, and can take pride in the fact that their ancestors are “those who explored neither the seas nor the sky, but who know in its most minute corners the land of suffering, those who have known voyages only through uprootings.”[15] The Cahier serves to demonstrate the power inherent in claiming an identity and a color that has been maligned and persecuted in European culture and totally transforming it into an affirmative force to be reckoned with in the post-colonial age.

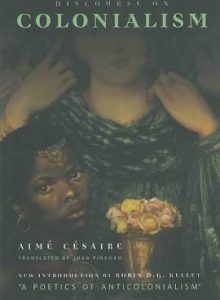

As a historical text, the Cahier poses certain difficulties that would make it challenging to teach in a modern European survey course without considerable elucidation and explanation. Teaching poetry, much less surrealist poetry, in an undergraduate history class is sometimes an uphill battle. Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism lends itself more readily to the task: here, the very structure of the Discourse and Césaire’s deep knowledge of and engagement with luminaries of France’s intellectual tradition put the text in dialogue with the ideals of the Enlightenment and the effort to come to terms with the Holocaust in the postwar years. Despite being an epic, which, as Ezra Pound defined it, is “a poem with some history in it,” the Cahier’s journey and heroic transformation are less accessible to students trying to comprehend the history of French and European decolonization. Nevertheless, some of the complications of the Cahier might work to bring out important questions of historical and literary interpretation and omissions and additions to a historical text.

The current literary dispute about which version of the poem is most authentic or rich sets up an interesting debate about how students should approach the work of an author who might have changed his mind over time. Is it right to privilege either the original or the most recent version of a text, especially if it appears to take up or emphasize different themes? What criteria should be used to compare the different versions, and how does historical context play a part in word choice and authorial intent? Does the fact that the 1956 version seems more political make it less valuable as a work of art?

Césaire’s resignation from the Communist Party in 1956 provides another interesting angle from which to explore the Cahier. In his letter to Maurice Thorez, Césaire proclaims:

We, men of color, at this precise moment in our historical evolution, have come to grasp, in our consciousness, the full breadth of our singularity…of our ‘situation in the world,’ which cannot be reduced to any other problem. The singularity of our history, constructed out of terrible misfortunes that belong to no one else. The singularity of our culture, which we wish to live in a way that is more and more real.[16]

This is a vivid example of historical intersectionality and the competing demands of different struggles for liberation in the 20th century. As a member of the French Communist Party (PCF), Césaire winced at Krushchev’s revelations about the murderous Stalinist regime, but even more damning was that as a man of color he could not tolerate that anti-racism would take a back seat to the class struggle for the PCF. In the new millennium, it is often difficult to get students to understand how communism was alive and threatening to the established order of the last century; that it was an ideology people would die, or kill for, and was taken seriously by governments, revolutionaries and intellectuals alike. Racism is more directly relevant to most students today, but few can understand the powerful force that Communism was in the minds of both its advocates and detractors in the postwar years. The fact that Aimé Césaire wrestled with these intertwining struggles, even altering his artistic creation over time, can humanize these competing claims on identity.

Finally, the question of intersectionality can highlight another question of omission in understanding this text. While the Cahier has rightly taken its place in the canon of Négritude and studies of the Black Atlantic, women’s contributions to this movement have all too often been overlooked. The creative friendship between Césaire, Damas, and Senghor during their student days in Paris is well-documented, but how often do we hear about the Nardal sisters, Martinican women whose Sunday literary salon made such fertile conversation possible? Paulette and Jeanne Nardal were writers, artists, and activists in their own right, students at the Sorbonne and crucial links between black French artists and African-Americans visiting Paris. Their uncle, Louis T. Achille, was a professor at Howard University and a friend of Ralph Bunche, and the Nardals’ extensive social contacts included friends like Marian Anderson and Claude McKay, in addition to Césaire, Damas, and Senghor. Friends remember Paulette repeating her maxim, “Black is beautiful!” at her well-attended literary salons. Not only a consummate hostess, Paulette was also a tireless advocate for Ethiopian independence after the Italian invasion and became a victim of fascist aggression herself when badly injured escaping a sinking ship torpedoed by the Germans in 1939.[17] Despite her lifelong pain and disability, Paulette was appointed to a post at the United Nations and stayed active in politics and civic engagement for the rest of her life. The Nardal sisters wrote about, and suffered from, the dual marginalization of women of color, and the omission of their names in a genealogy of Négritude would be another case in point.

Paulette and Jeanne Nardal were writers, artists, and activists in their own right, students at the Sorbonne and crucial links between black French artists and African-Americans visiting Paris. Their uncle, Louis T. Achille, was a professor at Howard University and a friend of Ralph Bunche, and the Nardals’ extensive social contacts included friends like Marian Anderson and Claude McKay, in addition to Césaire, Damas, and Senghor. Friends remember Paulette repeating her maxim, “Black is beautiful!” at her well-attended literary salons. Not only a consummate hostess, Paulette was also a tireless advocate for Ethiopian independence after the Italian invasion and became a victim of fascist aggression herself when badly injured escaping a sinking ship torpedoed by the Germans in 1939.[17] Despite her lifelong pain and disability, Paulette was appointed to a post at the United Nations and stayed active in politics and civic engagement for the rest of her life. The Nardal sisters wrote about, and suffered from, the dual marginalization of women of color, and the omission of their names in a genealogy of Négritude would be another case in point.

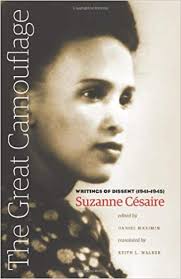

Similarly, Aimé Césaire’s own wife, Suzanne Césaire, was a formidable author and theoretician writing for Tropiques who transfixed André Breton on his layover in Martinique.  Suzanne Césaire was one of the first writers to articulate the notion of Créolité, a celebration of the mixed origins of Caribbean peoples, rather than the valorization of African heritage. Although Créolité is most closely associated with Antillean writers of the 1980s such as Patrick Chamoiseau, Jean Barnabé, and Raphaël Confiant, many of these images and themes were present in Suzanne Césaire’s work during the war years in Martinique.

Suzanne Césaire was one of the first writers to articulate the notion of Créolité, a celebration of the mixed origins of Caribbean peoples, rather than the valorization of African heritage. Although Créolité is most closely associated with Antillean writers of the 1980s such as Patrick Chamoiseau, Jean Barnabé, and Raphaël Confiant, many of these images and themes were present in Suzanne Césaire’s work during the war years in Martinique.  This doesn’t diminish the powerful impact of Aimé Césaire’s Cahier, but it should make students stop and think about whose texts and contributions are seen as path-breaking and what that says about historical transformation over time.

This doesn’t diminish the powerful impact of Aimé Césaire’s Cahier, but it should make students stop and think about whose texts and contributions are seen as path-breaking and what that says about historical transformation over time.

Teaching Césaire’s Cahier d’un retour au pays natal would be challenging in a history class. While the text’s canonical status is not in doubt, the jarring language, sexual imagery and Césaire’s relentless use of “nigger” throughout the poem would likely make many students, and teachers, uncomfortable. Yet discomfort is part of what Césaire was getting at, and this dynamic can be an effective educational tool when we understand what gives rise to it and how feelings of rejection and repulsion can be turned on their head.

Aimé Césaire, Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, translated by Clayton Eshleman and Annette Smith, Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

NOTES

- See Kristen Stromberg Childers, Seeking Imperialism’s Embrace: National Identity, Decolonization, and Assimilation in the French Caribbean, New York: Oxford University Press: 2016, p. 2.

- See Eric Jennings, “Last Exit from Vichy France: The Martinique Escape Route and the Ambiguities of Emigration,” Journal of Modern History, 74, No 2 (June 2002): 289-324, and Franklin Rosemont, “Introduction,” in André Breton, Martinique, Snake Charmer, translated by Andrew W. Seamen (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2008), 3-4.

- André Breton, “A Great Black Poet,” in Martinique, Snake Charmer,

- Lettre du Lieutenant de Vaisseau Bayle, Chef du service d’information au Directeur de la revue Tropiques, Fort-de-France, May 10, 1943, in Tropiques, 1941-1945: Collection complete (Paris: Éditions Jean-Michel Place, 1978).

- Réponse de Tropiques à M. le Lieutenant de Vaisseau Bayle, Fort-de-France, May 12, 1943, Tropiques, 1941-1945: Collection complete (Paris: Éditions Jean-Michel Place, 1978).

- Aimé Césaire, “Notebook of a Return to the Native Land,” translated by Clayton Eshleman and Annette Smith (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), p. 1.

- Césaire, “Notebook,” p. 12.

- Césaire, “Notebook,” p. 16.

- Césaire, “Notebook,” p. 24.

- Césaire, “Notebook,” p. 30.

- Césaire, “Notebook,” p. 33.

- Césaire, “Notebook,” p. 1.

- See A. James Arnold, “Césaire’s Notebook as Palimpsest: The Text before, during, and after World War II,” Research in African Literatures 35, no. 3: 133-40.

- See A. James Arnold, “Beyond Postcolonial Césaire: Reading Cahier d’un retour au pays natal Historically,” Forum for Modern Language Studies, 44, Issue 3, 1 July 2008: 258-275; Christopher L. Miller, “Editing and Editorializing: The New Genetic Cahier of Aimé Césaire,” South Atlantic Quarterly (2016), 115 (3): 441-455; and Malachi McIntosh, “The ‘I’ as Messiah in Césaire’s First Cahier,” Research in African Literatures 43:2 (Summer 2012): 77-94.

- Césaire, “Notebook,” p. 32.

- Aimé Césaire, “Letter to Maurice Thorez,” Paris, October 24, 1956, translated by Chike Jeffers, Social Text 103, Vol. 28, No. 2, Summer 2010, p. 147.

- See Annette Joseph-Gabriel, “When Pain is Political: Paulette Nardal and Black Women’s Citizenship in the French Empire,” Nursing Clio, October 12, 2018.

- See Emily Church, “In Search of Seven Sisters: A Biography of the Nardal Sisters of Martinique,” Callaloo, 36:2 (Spring 2013): 375-390.