Susan Whitney

Carleton University

Agnès Varda, who died on March 29, 2019 at age 90, was a singular figure in French cinema. A female director in an industry dominated by men and the lone woman associated with the New Wave, Varda came to directing from art history and photography and with little knowledge of film or its history. During a sixty-five year career, she experimented with genre and style, impressing critics with her originality and openness.

Varda enjoyed late-in-life transatlantic fame as a cinematic pioneer and quirky documentarist, appearing as character, narrator, and, increasingly, subject of her twenty-first century films. In 2015, Varda became the first woman to receive an honorary Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. The 2017 Visages Villages, made in collaboration with thirtysomething French photographer JR, won top honors in the Non Fiction category from the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Society of Film Critics. In 2018, Varda became the first woman director to receive an honorary Academy Award, delighting fashionistas by appearing on the red carpet in a Gucci silk pajama set. An elfin figure made instantly recognizable by her two-toned bowl cut of grey and purplish hair, the elderly Varda charmed more than she unsettled.

This had not always been the case. Agnès Varda was a feminist and an occasional maker of feminist films, of which L’Une chante, l’autre pas is the most striking example. When L’Une chante opened the 1977 New York Film Festival, it was met with applause and derision. Critics from both the New York Times and the New Yorker were dismissive, with Vincent Canby comparing it to “Soviet neo-realist art.” [1]

More than forty years later, #MeToo has shifted the lens through which cinematic portrayals of women and the struggle for rights are evaluated. Varda could be celebrated as both cinematic pioneer and feminist, not to mention as a director who was, remarkably, still making movies through her Paris-based production company, Ciné-Tamaris, at the time of her death. She was also still speaking out against gender discrimination. When eighty-two women took to the red carpet to protest gender inequality in the film industry at Cannes in May 2018, the diminutive eighty-nine-year old Varda led the protest alongside the actor and jury president, Cate Blanchett.

The #MeToo moment breathed new life into L’Une chante. Varda was invited to present a remastered version of the film in the Classics section at Cannes in May 2018. The film was subsequently re-released in France and in the United States, this time receiving positive notices. For the Los Angeles Times’ Justin Chang, the film was “enchantingly upbeat.” [2] History, it seemed, had caught up with Varda’s longstanding interest in women’s lives and feminist politics.

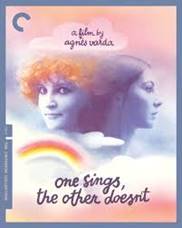

History as a discipline is similarly now better positioned to appreciate L’Une chante. After the “cultural turn” and almost five decades of the writing of women’s history, historians of France will find much of interest in the remastered version released by the Criterion Collection in 2019.

1970s French feminism has rarely been portrayed in feature films. Unlike most fictional films set in the late 1960s and early 1970s, L’Une chante is a product of the historical moment it depicts. It was shot almost contemporaneously to the events portrayed and draws on the director’s own experiences of feminist activism. Varda was, according to biographer Alison Smith, a committed but not militant feminist. [3] The director played, by her own admission, a small part in the era’s campaigns.[4] Varda signed the 1971 Manifesto of 343 women declaring that they had had illegal abortions and was involved with the Mouvement pour la Libération de l’Avortement et de la Contraception (MLAC), which arranged group excursions to Amsterdam for French women who sought to terminate their pregnancies before abortion was legalized in France in 1975. Although L’Une chante is a work of fiction, it includes the occasional historical event and actor. Varda herself viewed the film as “une fiction documentée.” [5] Just what Varda meant – and achieved—by “fiction documentée” can be profitably discussed in courses on film and history.

1970s French feminism has rarely been portrayed in feature films. Unlike most fictional films set in the late 1960s and early 1970s, L’Une chante is a product of the historical moment it depicts. It was shot almost contemporaneously to the events portrayed and draws on the director’s own experiences of feminist activism. Varda was, according to biographer Alison Smith, a committed but not militant feminist. [3] The director played, by her own admission, a small part in the era’s campaigns.[4] Varda signed the 1971 Manifesto of 343 women declaring that they had had illegal abortions and was involved with the Mouvement pour la Libération de l’Avortement et de la Contraception (MLAC), which arranged group excursions to Amsterdam for French women who sought to terminate their pregnancies before abortion was legalized in France in 1975. Although L’Une chante is a work of fiction, it includes the occasional historical event and actor. Varda herself viewed the film as “une fiction documentée.” [5] Just what Varda meant – and achieved—by “fiction documentée” can be profitably discussed in courses on film and history.

L’une chante follows the deep and sustaining friendship between two very different French young women, Pauline, who sings, and Suzanne, who does not. Theirs is a friendship forged in the tragic circumstances accompanying an unwanted pregnancy and an illegal abortion. It is also a friendship set against the campaign for reproductive rights in early 1970s France. Over the course of the film, Pauline’s and Suzanne’s professional and personal lives are transformed by their engagement with feminist ideas and politics.

The film opens in Paris in 1962, when Pauline, a seventeen-year old lycéenne, is drawn into a photographic gallery whose walls are covered by photos of women, many of them with grim countenances and some of them nude. The photographs simultaneously unnerve and intrigue Pauline. She realizes that one woman photographed with two young children is someone she remembers as an unwed mother from her neighborhood. From a conversation with the photographer, Jérôme, Pauline discovers that the woman, Suzanne, lives with Jérôme. The children are his, even if we learn from a later scene that he has no emotional connection to them. He is, we learn later, still married to someone else.

After we watch schoolgirl Pauline eat supper with her conventional, petit bourgeois parents, clash with her patriarchal father, and attend choir practice, she pays a visit to Suzanne. The visit begins the young women’s friendship. It also introduces the question of reproductive rights that will become so critical to the narrative. When Pauline arrives at the tiny, sparsely furnished apartment that Suzanne and her two young children share with Jérôme, she discovers that Suzanne is pregnant and deeply depressed, without either the financial or emotional wherewithal to act. Pauline is shocked by how old the twenty-two year old Suzanne appears (Suzanne herself says she feels a hundred), and she urges Suzanne not to give birth to another child.

Pauline resolves to help Suzanne procure an abortion. Her task is complicated by Pauline’s own ignorance and by the unexplained historical context. France in 1962 was governed by a punitive, natalist reproductive regime put in place in the aftermath of the First World War. Neither contraception nor abortion could be legally obtained by women and abortions were punishable by fines and imprisonment. In her search for information, Pauline turns first to her female philosophy teacher, who has been teaching the schoolgirls about free will. When that not surprisingly yields nothing, she does what women so often did. She turns to other women, in this case the young women in her choir. One of them explains Suzanne’s options: pregnant women can go either to a local illegal abortionist or to a clinic in Switzerland. Going to Switzerland is the safer but more expensive option. Even there, Pauline informs Suzanne, she will have to plead her case before a four-person panel.

To raise the necessary funds for her new friend, Pauline invents a choir trip to Avignon and asks her parents for 20,000 francs to finance the trip. In handing the money over to Suzanne, Pauline implores her friend to use it to go to Switzerland. After Suzanne sets off, presumably for Switzerland, Pauline moves into Suzanne’s apartment to look after the two young children. Of Suzanne’s journey, Varda shows only a brief clip, in which the character sits, dejected, in a metro car. The film later reveals that Suzanne did not travel to Switzerland, but rather went to the local abortionist. She used the remaining money to pay outstanding bills.

Pauline, meanwhile, defies her parents by dropping out of school to pursue her dream of becoming a singer. She moves out of her parents’ old-fashioned apartment and into a modern apartment with a friend. That Pauline never seems to worry about money underlines the class differences between the two main characters. The scenes devoted to Pauline’s pursuit of a commercial music career nicely evoke teenagers’ enthusiasm for rock’n’roll in early 1960s France. They also suggest the dreams of fame and fortune that successful young female singers such as Sylvie Vartan and Françoise Hardy inspired among teenage girls. Interestingly, Pauline was not the first major early 1960s Varda character who was a chanteuse. Cléo in the 1962 film Cléo de 5 à 7 had also been a singer. Yet the two young women’s singing careers follow different trajectories. Cléo was a commercial artist while Pauline shifts to feminist musical performance after failing to achieve her dream of commercial success. In an amusing scene, Pauline and her unnamed friend sing back up for a male rocker who resembles an ugly, unsexy Johnny Hallyday.

If Suzanne’s unwanted pregnancy brings Pauline and Suzanne together, they are driven apart by Jérôme’s suicide, which they discover together after breaking into his shuttered shop. In the aftermath of this tragedy, the young women go their separate ways for ten years, only to rediscover each other as adults in 1972 at a protest outside an abortion trial in Bobigny.

In these scenes, Varda inserts the protagonists into history. The 1972 trial of sixteen-year old Marie-Claude Chevalier became a milestone in the long campaign to legalize abortion in France. The schoolgirl was being tried for having had an illegal abortion after being raped by a fellow lycée student. The abortionist and the girl’s mother, a single mother who had helped her daughter arrange the abortion, were tried separately. The renowned Tunisian-French feminist lawyer Gisèle Halimi, who made her name defending Algerian nationals during the Algerian War, represented Chevalier. Halimi recruited celebrities and male doctors to help make her case — and to draw attention to the trial and to the injustice of France’s antiquated abortion legislation. The schoolgirl was acquitted, although her mother received a small fine in a separate trial. The abortionist was sentenced to a year in prison. [6]

Varda is not interested in the specifics of the trial, however. Instead, the camera remains trained on the anonymous crowds gathered outside the courtroom. Varda enlists Halimi to play herself in a brief cameo. The robed lawyer exits the courtroom to pull a few colleagues past the police barricades holding back the crowds. The recreated crowd scenes in L’Une chante are brighter and warmer than contemporary ina film clips show them to be.

By this time, both Pauline’s and Suzanne’s lives have become intertwined with the women’s movement. Pauline travels around France performing with a feminist singing group while Suzanne works as a family planning counselor in the south of France. It is Pauline’s performance of “Mon corps est à moi” outside the courthouse that brings her to Suzanne’s attention. But the friends only have time for a brief reunion before Suzanne and her thirteen-year old daughter must board a bus and return to their home in the south of France. The two bring each other up to date through letters and postcards, their correspondence allowing Varda to tell the story of their last ten years through flashbacks.

Varda’s depiction of Suzanne and Pauline’s lives between 1962 and 1972 include numerous sequences that could be fruitfully shown to students in courses on twentieth-century France. After Jérôme’s suicide, Suzanne returns with her young children to her parents’ farm. The farm scenes paint a grim portrait of traditional, rural France, especially with reference to opportunities for women. The housing stock is centuries old, the labor is back-breaking, and the attitudes are patriarchal. When a meal is ready, Suzanne’s mother gruffly commands her, “Amènes tes bâtards.” Her father is even less supportive. One wonders whether Varda was intentionally challenging either the back-to-land movements that emerged after Mai ’68 or the romanticized view of rural life held by many in 1970s France, which has been analyzed by Sarah Farmer. [7] Pairing the scenes with Farmer’s article could provide the basis for an interesting discussion of rural life in postwar France.

The scenes are especially evocative of the circumstances facing young rural French women. Students who watch them will have no difficulty understanding why young women fled rural France for Paris and other French cities throughout the twentieth century. Always the more quietly determined of the two friends, Suzanne draws sustenance from her children’s delight in their rural surroundings as she prepares her escape. She teaches herself to type, persevering even when her father banishes her to the frigid barn, gets work in a factory, becomes a medical secretary, and ultimately finds work at a family planning center after Mai ’68. Always she finds support in the “famille des femmes.” Suzanne is transformed, somewhat miraculously, into an entirely different woman, a confident quasi-professional who bears no relationship to the downtrodden, depressed young woman of earlier in the film.

Meanwhile, the rebellious and free-spirited Pauline travels around the country with other feminists performing songs such as “Je suis femme, Je suis moi” and feminist agitprop theater to mostly perplexed local crowds, who are sometimes drawn out of their houses by the noise. Again, fact is blended with fiction as Pauline’s fellow singers come from the real group, Orchidée. The contrast between traditional France and new ways of thinking on display in these scenes is stark and could be profitably shown to students as the basis of a discussion on how social and cultural change occurs – and at what speed. The march of events, including a process such as the modernization of postwar France, can appear seamless when treated historically. Yet social and cultural change occurs much more haltingly — and is often resisted.

Much attention is given to a trip Pauline takes to Amsterdam, where she travels in the company of other women to have an abortion that she cannot legally have in France. Here Varda draws on her own experience with the group abortion trips to Amsterdam organized by the Mouvement pour la Libération de l’Avortement et de la Contraception. The trip is portrayed in a remarkably positive light. Having an abortion does not seem to upset Pauline. Instead, it is in Amsterdam that Pauline meets the Iranian man, Darius, whom she will eventually marry. It is in Amsterdam too that she composes her first song. And it is in Amsterdam, the narrator tells us, that Pauline, now known as Pomme, most fully experiences the power that flows from the community of women.

In an interview done after L’Une chante was remastered, Varda explained that she had wanted to make a joyful film about the early 1970s feminist demand that women be able to choose the children to whom they gave birth. [8] “Si je veux, quand je veux” the slogan went. To make the feminist declarations and slogans more palatable, Varda continued, she conveyed them through songs whose lyrics she wrote herself. Ultimately, the songs, which are a highlight of the film, convey both the earnestness and the zaniness of some early 1970s feminist protest. Showing students clips of song performances would enliven a discussion of 1970s French feminism.

Varda’s “fiction documentée” never claims to be a documentary. Nor is it interested in the numerous organizations and individual actors involved in the struggle for reproductive rights in postwar France. A precursor to BPM, which brought to life Paris ACT UP in the early 1990s, this is not. In many ways, L’Une chante is an ode to the power of women’s community and female friendship. As such, it is redolent of key strands in late 1970s and early 1980s women’s history. Pauline and Suzanne share a deep, almost inexplicably deep, bond, one forged in the trauma of Suzanne’s unwanted pregnancy and Jérôme’s suicide. So important is Suzanne to Pauline that she often muses about her friend at the most surprising moments, including after lovemaking with Darius. Even though men played key roles in the struggle for reproductive rights in France, they are relegated to minor, emotionally supportive roles here.

The vision of female friendship presented here is of the one-dimensional, heroic variety. Absent is the emotional complexity found in more recent fictional explorations, such as those of Elena Ferrante. Absent as well are the tensions between feminist organizations and the often divisive debates within organizations that have been explored recently by scholars. [9] Nowhere in the film are the attacks on Simone Veil, President Giscard d’Estaing’s Minister of Health (and the Fifth Republic’s first female Minister), that occurred during the parliamentary debates over Veil’s bill legalizing “l’interruption volontaire de grossesse” in late 1974.

Ultimately, there is an optimistic, even utopian quality to Varda’s treatment of female friendship and feminism, as well as to the film itself. It ends in gauzy shots of the film’s characters as they vacation together during the summer of 1976. By this point, Suzanne has finally found love with a divorced (male) doctor and Pauline has given birth to two children, left her husband, and created a new feminist family. Both women, the viewer is told, have found happiness and contentment. The film ends with the narrator explaining that the two women’s friendship had flowed easily, that they were different but alike, and that they had fought to gain the happiness of women. Their struggle, it is hoped, will help the next generation of women, including Marie, Suzanne’s daughter. The camera rests finally on the face of Marie, played at this age by Varda’s own daughter, Rosalie, to whom the film is dedicated. The sentiments evoke the utopian strands of early 1970s feminism. But in our polarized, jaded times, maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

Agnès Varda, Director, L’une chante, l’autre pas [One Sings, the Other Doesn’t], 1977, Color, 120 min, Venezuela, France, Belgium, Soviet Union, Ciné Tamaris, INLC, INA, Paradise, Population, SFP

- Vincent Canby, “Film Festival: Varda’s ‘One Sings,’” New York Times, September 23, 1977.

- Justin Chang, Los Angeles Times, July 23, 2018.

- Alison Smith, Agnès Varda (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), p. 8.

- Agnès Varda, Varda par Agnès (Paris: Editions Cahiers du Cinéma), p. 94.

- Varda, Varda par Agnès, p. 110.

- Lisa Greenwald, Daughters of 1968: Redefining French Feminism and the Women’s Liberation Movement (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), pp. 160-163.

- Sarah Farmer, “Memoirs of French Peasant Life: Progress and Nostalgia in Postwar France,” French History, Vol. 25, No. 3 (2011), pp. 362-379.

- https://www.arte.tv/fr/videos/081907-019-A/l-une-chante-l-autre-pas-rencontre-avec-agnes-varda/

- See, for example, Bibia Pavard, Si je veux, quand je veux: Contraception et avortement dans la société française (1956-1979) (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes), 2012.