Colin Jones

Queen Mary University of London and University of Chicago

Why read A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens’s famous 1859 account of Paris and London in the Age of Revolutions? [1] Indeed, these days why read any Dickens at all? Scarcely a month goes by without the charge-sheet against this icon of the English literary canon lengthening. Dickens’s xenophobic outbursts and overt anti-Semitism have long been noted with regret. But it is his outspoken racism and support for colonialism that perhaps jars most in the age of Black Lives Matter. The historian and broadcaster David Olosuga recently pointed out how Dickens’s famed compassion evaporates when faced with non-white individuals: “I adore Dickens but it just makes me sad” – hardly the strongest of endorsements.[2]

Since I was a child, I have always loved A Tale of Two Cities, and I have researched the novel and written in the past about its impact on British culture. Reading it today also makes me sad about its author’s feet of clay (though racial and colonial themes are absent from A Tale of Two Cities, thank heavens). But I am also saddened that the novel has been so relentlessly harnessed to narrow and jingoistic interpretations that, I believe, are at the antipodes from Dickens’s intentions and the underlying messages that he crafted within the novel. The novel is invariably taken to be playing strongly to Dickens’s “Little England”-ism, while pushing an underlying message about the horrors of the French Revolutionary tradition, that allegedly bolsters the peaceful political evolutionism on which Victorian Britain complacently prided itself.

In this essay on the novel, I would like to debunk this entrenched view that associates it with strident English nationalism and Francophobia, and, setting it in the context of Dickens’s life and works, to argue that we should revalue and indeed treasure it as a work of generous transnational inspiration. In so doing, I would like to pay tribute to Liana Vardi’s role as founding and long-serving animatrice of H-France’s “Fiction and Film for Scholars of France” bulletin. The bulletin is a beacon of transnational understanding of something that as contributors we all treasure: France.

DICKENS FRANCOPHILE

Dickens was much more cosmopolitan than chauvinistic in his outlook, and more Francophile than Francophobe than is generally accounted. He excoriated those of his compatriots who, basing their prejudices on outdated anti-Revolutionary Gillray caricatures, viewed the French as “benighted frog-eaters.” He particularly adored Paris. It was love at first sight on his first, 1844 encounter. He lived there for nearly a year in 1846-7, and most of his twenty-odd later visits to France, down to his death in 1870, were to the city. Paris was “the most extraordinary place in the world,” he noted on one occasion:

I walked about the streets, in and out, up and down, backwards and forwards – and every house and every person I passed seemed to be another leaf in the enormous book which stands wide-open there.[3]

He developed enormous respect for French art, theatre, culture and civility, saluting the French as “in many high and great respects the first people in the universe.” And he prided himself as “an accomplished Frenchman” and of writing “le langage des Dieux et des Anges.” His son wrote of him that “he used to say laughingly that his sympathies were so much with the French that he ought to have been born a Frenchman.” On one occasion, again jocularly, but again revealingly, he even signed himself “Charles Dickens, Français naturalisé, et Citoyen de Paris.” He seems to have felt as comfortable with this ascription as with the moustache which he grew at about the same time. It was, he noted, “the pride of Albion and the admiration of Gaul”…. Even Dickens’s moustache boasted a transnational identity.[4]

Whereas for Baudelaire, proto-theorist of flânerie, the urban development and boulevardisation wrought by Haussmann in Second Empire Paris nurtured a plangent nostalgia for lost worlds, Dickens’s attitude in the face of urban improvement was, in contrast, akin to wonderment. In 1853, he remarked to his wife that

Paris is very full, extraordinarily gay and wonderfully improving. Thousands of houses must have been pulled down for the construction of an immense street now in the making from the dirty old end of the Rue de Tivoli [sic], past the Palais Royal, away beyond the Hôtel de Ville. It will be the finest thing in Europe.

He was aware of the grim side of Paris under the Second Empire, but this did not stop him was marveling at all that had been achieved in the city as a whole: “Wherever I look I see astounding new works, doing or done.”[5]

Dickens prided himself on his extraordinary detailed knowledge of his native London from east to west, “from Bow to Brentford.” Long night-walks and extensive daytime perambulations meant that he knew it “better than any one other man of all its million.” Yet in terms of his feelings, there was no comparison. London was, he grumbled in 1851,

a vile place. I have never taken to it since I lived abroad. Whenever I come back from the country now and see that great heavy canopy lowering over the housetops I wonder what on earth I do there except on obligation.[6]

He deplored “the shabbiness of our English capital.” It was “hideous to behold” its ugliness “quite astonishing.”

The meanness of Regent Street set against the great line of the Boulevards in Paris is as striking as the abortive ugliness of Trafalgar Square set against the gallant beauty of the Place de la Concorde… No Englishmen knows what gaslight is, until he sees the Rue de Rivoli and the Palais Royal after dark.[7]

He was infuriated that the “ridiculous corporation” of London proceeded at tortoise pace while the city of Paris raced ahead on the pathway to urban modernity:

The citizens of London and the citizens of Paris can be compared and contrasted in almost the same terms as the cities themselves. [T]he one [is] sombre heavy, large, continually expanding, seldom changing; the other bright, compact, open, lively and ever improving. The pace of London improvement is that of the overgrown alderman or of his beloved turtle… When while the wise men of the East have been haggling about one little piece of open ground at the base of St Paul’s cathedral, a considerable portion of the capital of the great French empire has been not only razed but rebuilt.[8]

Dickens loved the cultural whirl of Paris as well as its built environment. His celebrity assured by the swift translation of his novels into French, he enjoyed face-recognition in the street. He was particularly eager to have what he accounted “the best story I have ever written” speedily translated into French. It was, he told his publishing house, Hachette, “un de mes espoirs les plus ardents en l’écrivant.” He was by then already exploring the possibility of putting on in Paris a stage version of the novel which he held would be of great interest to the French, “because it treats of a very memorable time in France.” Its plot was genuinely Anglo-French, covering goings-on within the two national capitals between 1775 and 1794, from the early reign of Louis XVI to the height of the Terror. Yet it was a story set in private rather than public life – no political figure, French or English, is even mentioned. The emphasis was on the experience of ordinary people: how “myriads of small creatures, the creatures of this chronicle amongst them” faced a historical moment that was (to reference the novel’s opening the words), “the best of times… [and] the worst of times.”[9]

At the centre of the plot is a French woman, living in London, Lucy Manette. Her physician father had been unjustly imprisoned in the Bastille in the 1770s, and at the start of the novel is freed from it. Lucy becomes the centre of a love intrigue involving two rivals for her hand who resemble each other physically. On one hand there is Sydney Carton, the novel’s héros maudit, a brilliant lawyer, but a cynic and a drunkard. Then there is Carton’s doppelganger, Charles Darnay, who abandons his cruel French aristocrat uncle, the marquis d’Evrémonde, and emigrates to work as a language teacher in London. Darnay prevails over Carton and marries Lucy Manette. However, tricked into returning to Paris at the height of the Terror, Darnay is sent before the Revolutionary Tribunal and, as his wicked uncle’s heir, condemned to death as a ci-devant. In the novel’s climax, Carton redeems himself by substituting himself for his double in his prison cell. Carton goes stoically and heroically to his death by guillotine to allow the Darnays to escape the city en famille. His imagined peroration as he proceeds up the steps to the guillotine, to save the happiness of his beloved Lucy – “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done” – swiftly became a much-quoted and still enduring catch-phrase in British culture.[10] Yet Dickens’s hopes for the novel in France were dashed: the novel was translated but made little impact, and there was no French stage version.[11]

RECEPTION

The story of A Tale of Two Cities in England and France is a tale of two receptions. The French have never warmed to the novel, even though Dickens’s fiction has generally found a warm reception among them. While David Copperfield, for example, has gone into scores of French translations and versions since its publication in French, ATOTC has scarcely reached double figures. Comically symptomatic of the failure of the novel to capture the national imagination has been an inability to agree on a title in French for it. The literal translation – Un conte de deux villes – was long rejected, presumably on grounds of dysphony (the ugly ‘de deux’). For most of its history, it has traded under the title Paris et Londres en 1793, whereas in fact the action in the novel covers the whole period 1775 to 1794. If the novel is known much at all in France in our day it is probably more through film and TV adaptations.

French readers have tended to prefer their Dickens full of loveable characters, jocular, quintessentially English humour, whimsical dialogue and mawkishly sentimental high spots. They have found it difficult to know what to do with a novel whose ideological pay-load seemed not to fit into views of the Revolution held on either the Right or the Left. Generally, it has been classified as an attack on the Revolution and on French republicanism, and put on a par with Baronness d’Orzy’s Scarlet Pimpernel pot-boilers.

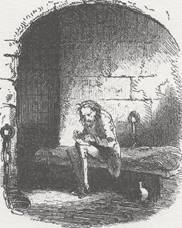

It is certainly true that the images that the novel presents of the French Revolution, and notably of the Reign of Terror in 1793-4 when it climaxes, are highly negative. The vengeful bloodlust of the Amazonian sans-culotte, Madame Defarge, makes her one of the least sympathetic characters in Dickens’s oeuvre. Some of the Parisian set-piece scenes in the depiction of the Terror have become classics of political nightmare: the dank, dungeon chill of Manette’s cell in the Bastille; the Kafka-esque atmosphere of the Revolutionary Tribunal; the hideous account of the Carmagnole revolutionary dance, with tricolor-bedecked sans-culottes shrieking frenetically as the guillotine blade is sharpened; Madame Defarge counting the stitches in her knitting as heads fall; and the revolutionary mob “all alike and armed in hunger and rage,” “headlong, mad and dangerous” and primed for maximum atrocity. Hovering menacingly over it all, the grim, personalised characterisation of Paris’s Faubourg Saint-Antoine, poverty-stricken centre of revolutionary violence and in its way one of the principal actors in the drama.[12]

Revolutionary violence in Tale of Two Cities (left), Dr. Manette in his cell (right)

In contrast to the quizzical and rejecting reception the novel received in France is the warmly impassioned and hyper-enthused reception it received in England. Sales figures were high from the start, and reviews eulogistic throughout Dickens’s life. But after his death in 1870, its reception took a significant twist, stimulated by the stage version of the novel created by the impresario John Martin Harvey, The Only Way.[13] This enjoyed huge success, which was ratcheted up dramatically when in the Boer War, the English commander at the siege of Mafeking in 1899, General Robert Baden Powell (subsequent founder of the Boy Scout movement) kept up morale among the troops by staging a production of The Only Way. Sydney Carton’s final, dying words on the scaffold – ‘it is a far, far better thing’- seemed apt for that Mafeking moment, as it would do for other moments of personal and national sacrifice. In the Great War, Martin Harvey played his Carton to British foot soldiers in the trenches, with bombs whistling round his ears. It was for “their beloved Tale of Two Cities,” he noted in his memoirs, that “they always called.” It did not appear to matter that the enemy in the play were not the Germans but the French, who were after all Britain’s allies: the ways of national ‘othering’ can be very strange. What was crucial about the play and particularly the final scene was less the precise national identity of Carton’s executioners than the opportunity the death-scene afforded in the construction of a melodramatic yet peculiarly potent form of stoical English, stiff-upper-lip masculinity. Paradoxically, it is Sydney Carton’s capacity to lose his head while others all around him were keeping theirs which marks him out as a model Edwardian, Kipling-esque man.

The Only Way was still a regular in provincial repertory in England down to the outbreak of the Second World War. By then its chauvinist appeal had been magnified by film versions, first in 1925 and then in a 1935 Hollywood version of A Tale of Two Cities, with the actor and quintessential stage Englishman Ronald Coleman putting in a brilliant, definitional performance as Sydney Carton. Self-sacrifice for love seemed the height of a certain form of national identity. This, despite the fact that the objects of Carton’s sacrifice, Lucy Manette and Charles Darnay, were both French nationals – a generally overlooked transnational point.

ENTANGLED NARRATIVES

The ways in which the mediatised post-mortem reception of Dickens’s story within British culture fed jingoistic and masculinist fantasies of national identity well into the twentieth century would have surprised Dickens. He had eagerly expected that the French would be highly receptive to his story. He hoped that it would strengthen Anglo-French ties, not envenom them.

Dickens must have imagined that readers would note how his highly negative view of the Revolutionary Terror was in fact exceeded by his even more negative depiction of Ancien Régime society: however tyrannical the Terror, in other words, the Ancien Régime was worse. The depiction of the seigneurial system and court life of the villainous marquis d’Evrémonde is distilled, almost comic-book evil: peasants ground down and starving, feudal rights (including the droit du seigneur) brutally enforced, utter insouciance shown for life and limb (a key episode involves the marquis’s coach, driven at headlong speed through the streets of Paris killing the child of a future sans-culotte). The tyranny of the Terror merely replicated the tyranny of the Ancien Régime. If not forgivable, the violence of the Terror was understandable in terms of what the poor had had to endure before 1789. Dickens’s overall moral was, “Crush humanity out of shape once more, under similar hammers, and it will twist itself into the same tortured forms.”[14]

The idea that the Terror was in essence popular revenge for what had gone before is particularly evident in regard to the role of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which Dickens portrayed as a monstrous collective actor in the Revolutionary drama. He memorably described the features of the Faubourg as “cold, dirt, sickness, ignorance and want.”[15] The principal fault lay with a social and political system which allowed them to persist, rather than those who suffered their vicissitudes. The Parisian revolutionaries had been forced into outrageous violence by the violence of what had gone on before under the watch of the aristocracy. Even the sans-culotte tricoteuse Madame Defarge is revealed towards the end of the novel to have been traumatised as a young woman by the brutal rape and murder of her sister by the marquis d’Evrémonde. The real villains of A Tale of Two Cities were the aristocratic ruling class prior to 1789.

Dickens’s reputation as the champion of the poor and the scourge of the British ruling classes is well-known, so it is not surprising in a way that he should target the French aristocracy in this way. The plot and message of A Tale of Two Cities was thus tangled up with his political views about Britain. This is further confirmed when we scrutinise the sources on which Dickens drew for his novel, and in particular for his account of popular violence.

In undertaking research on the novel, I scrutinised not only the novel itself, but also Dickens’s copious correspondence and his journalism and other writings on the city, with the aim of trying to reconstruct his Parisian psychogeography. What emerges from an analysis of the novelist’s movements about the city during his many visits was a very strong preference for the obvious tourist hotspots of the period, notably the west-central area, the Grand Boulevards and the Champs-Elysées. As it turns out, there is no recorded evidence that Dickens ever once set foot within the Faubourg Saint-Antoine.[16] An inveterate walker, he is known to have skirted the city’s walls north of the Seine, and he was a regular visitor to the theatres of the Boulevard du Temple, on the western rim of the Faubourg. But he never penetrated further east. The graphic description in the novel of the poverty and distress prevalent there was not based on any physical encounter whatever with the area, which retained its radical reputation and its social complexion well into the Second Empire. To use Henri Lefebvre’s terminology, the “representational space” of Paris in the novel did not correspond to Dickens’s own “spatial practices” within the city.[17] The novelist knew Paris well; but when it came to the Faubourg Saint-Antoine he knew nothing by first hand whereof he spoke.

The sources on which Dickens appears to have drawn in his imagining of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, were highly entangled and Anglo-French. Thomas Carlyle guided him through the copious primary printed sources in French available in the London Library, and there are evident borrowings in the novel from Mercier’s Tableau de Paris and Riouffe’s Mémoires sur les prisons as well as from Arthur Young’s Travels in France. But his imagination was fired by experiences beyond the printed page. He was an avid visitor to elaborately-staged melodramas on and around the Boulevard du Temple (or the Boulevard du crime as it was known because of the sensational plots played out there). He referred to his novel as “like a French drama,” and we can trace in the novel the influence of the melodramatic plots and the staging he there witnessed. Surprisingly perhaps, his visits to public showings of cadavres at the Paris Morgue and, in London, to Madame Tussaud’s famous waxworks also gave him material that he put to use in several places in the novel. Yet the biggest influence on his descriptions of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine was, paradoxically, London rather than Paris.[18]

Dickens did not witness in Paris the “cold, dirt, sickness, ignorance and want” that he described as “the tutelary deities” of the Faubourg. He never went there. But he was deeply versed in their presence in the poorest neighbourhoods of London. The grim features of the plebeian urban landscape in the novel may be traced back to London’s East End, a terrain with which he was highly familiar. Here lurked an old-style poverty, kept in place by an inert local government system which blocked change in all its forms. Furthermore, although Dickens never saw a Parisian crowd with its anger roused, he had a close, sometimes uncomfortable knowledge of English collective violence with crowds acting “like herds of swine.” It was in London, not Paris that he witnessed public executions alongside their customary rough, plebeian audience: Tyburn gallows was his model for the guillotine setting. The chaotic trial scene at London’s Old Bailey in the novel bears comparison with the travesties of justice meted out at the Revolutionary Tribunal. And it was Newgate gaol that he knew from personal experience, not the La Force prison on the edge of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, where Charles Darnay was imprisoned.

The destruction of the old Newgate prison by the crowds mobilised in the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780 is, in fact, one of the great set-piece scenes of Dickens’s novel, Barnaby Rudge, published in 1841, nearly two decades before A Tale of Two Cities.[19] The only other historical novel that Dickens wrote, and one of his least appreciated works, it is, however, crucial in this respect. For when one looks at descriptions of crowd violence in the two novels, one sees a distinct prefiguration of popular collective violence in Revolutionary Paris in Dickens’s accounts of the London Gordon Riots. Dickens was born too late to have witnessed the riots in person, but at the time he wrote a few smoking embers still remained from the political conflagrations that had accompanied the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. The Great Reform Act of 1832 had also racked up popular involvement in conventional politics. Extra-parliamentary movements with a strong popular base – notably the anti-poor law agitation and Chartism – seemed much more worrying to Dickens than they may to us with benefit of hindsight. The years in which Dickens wrote Barnaby Rudge saw the redaction of the first people’s Charter (1838), the insurrectionary Newport Rising (1839) and numerous other outbreaks of popular agitation. Chartist newspapers published Buonarrotti’s account of the Babeuf conspiracy in this period too. In 1837 the radical Bronterre O’Brien had published a life of Robespierre. The anxiety that gripped Dickens when he wrote Barnaby Rudge was still in place when he composed A Tale of Two Cities, and the earlier novel acted as a prism through which he imagined crowd violence and revolutionary politics in the French story.

The tangled, inter-textual web of reference linking Barnaby Rudge with A Tale of Two Cities confirms the fallacy of assuming that the latter is some sort of Francophobic, “Little-England” novel. It was not the French whom Dickens was attacking in his story, it was the idea of violent revolutionary action tout court. Insofar as he held that the aetiology of collective violence lay in prior mistreatment, the main causes of revolutions were ruling classes not acting humanely and responsibly to remedy social evils and glaring inequality. If ever there was a case of an author’s intentions being thwarted and turned on their head by its reception, it is A Tale of Two Cities. Seen in a transnational prism, the novel seems not at all a paean to plucky English nationalism, but rather what Dickens intended: a political parable, a moral tract for the times winged towards the English ruling classes.

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1988)

NOTES

- In this essay, I draw on research published a few years ago, notably Colin Jones, Josephine McDonagh and John Mee (eds) Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities and the French Revolution (Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); and Colin Jones, “Presidential Address. French Crossings I: Tales of Two Cities,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 20 (2010), pp. 1–26. I take the story forward to look more closely at theatre and film adaptations in “Charles Dickens’s Two Cities,” in Alastair Phillips & Ginette Vincendeau (eds), Paris in the Cinema: Beyond the ‘Flâneur’ (London: Palgrave, on behalf of the British Film Institute, 2018). The Penguin Classics edition of the novel (hereafter abbreviated as ATOTC), edited by Richard Maxwell, first published in 1988, is recommended. For Dickens’s other writings in which one can chart his relationship with Paris, I also consulted Dickens’s correspondence and journalism, for which I have used the authoritative The British Academy Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens, ed. Graham Storey et al. (12 vols., Oxford, 1965–2002), and The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens’ Journalism, ed. Michael Slater and John Drew (4 vols., 1994–2000). Michael Slater’s definitional biography, Charles Dickens (Yales University Press: London, 2009), supersedes earlier lives.

- Interview with David Olosuga, Daily Telegraph, 11 October 2020.

- Letters, IV, pp. 166-7

- Journalism, III, p. 332 (‘frog-eaters’); and Jones, “Tales of Two Cities,” p. 12.

- Letters, VII, p. 163; & X, p. 151.

- For Dickens and London walks, see Jeremy Tambling, Going Astray. Dickens and London (Pearson: Harlow, 2009). See too Letters, IV, p. 289 (“a vile place”).

- Journalism, VI, p. 287.

- “Paris Improved,” Household Words, November 1855, p. 361.

- ATOTC, p. 7.

- ATOTC, p. 389.a

- Letters, IV, p. 249 ; IV, pp. 132, 163.

- ATOTC, pp. 222, 224, 230.

- For the stage versions, see Joss Marsh, “Mimi and the Matinee Idol: John Martin-Harvey, Sydney Carton and the Staging of ATOTC,” in Jones et al, Charles Dickens, pp. 126-45. For film versions, Jones. “Charles Dickens’s Two Cities.”

- ATOTC, p. 385.

- ATOTC, p. 32.

- See the map (p. 14) & discussion in Jones, “A Tale of Two Cities,” pp. 14-16.

- Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford, 1991).

- F. Kaplan, ed., Charles Dickens’s Book of Memoranda (New York, 1981), 1855, no.21 (no pagination) (“like a French drama”). For the sources generally, see the overview in Jones, “Tales of Two Cities,” pp. 16-22.

- Barnaby Rudge, Penguin Classics, ed. John Bowen (Harmondsworth, 2003).