Dominica Chang

Lawrence University

Gustave Flaubert’s L’Education sentimentale (1869), the quintessential novel of the 1848 French revolutionary experience, is rarely taught at the undergraduate or even graduate level. The practical reasons for this are understandable: at over 400 pages, the novel’s length occupies significant real estate on a limited syllabus (particularly if used as a supplement to a History course); moreover, its exceptionally specific cultural and historical content, unconventional form, numerous intertextual references, and fragmented narrative style all demand considerable time, effort, and patience from both instructors and students. When taught, then, it is often the novel’s purely historical value that is discussed, in particular, its remarkable depiction of the tumultuous period from the 1848 February Days to Louis-Napoleon’s 1851 coup d’état. Indeed, Sentimental Education is rightly considered, along with Alexis de Toqueville’s Souvenirs (1893) and Karl Marx’s writings on the event, to be required reading for all scholars and students of French and European revolutionary history. The 1848 Revolution itself, however, only begins in Part III of the novel, close to 300 pages into the narrative! If we do choose to teach L’Education as a “1848 novel,” do we ask our students to skim or simply to endure the first two parts? Or, do we make our lives easier by skipping two-thirds of the novel and assigning only Part III? Perhaps we avoid the problem entirely by not teaching it at all? My objective here is two-fold: first, I would like to persuade fellow 19th-century French scholars, especially historians, to re-read Flaubert’s Sentimental Education with a mind to including it on relevant future syllabi; and secondly, for those who ultimately decide to teach it, I will share specific critical approaches and pedagogical strategies that will hopefully make the entirety of this challenging novel not only more rewarding for instructors to teach, but also much more accessible to and meaningful for our 21st-century (predominantly) young adult readers. As I hope to convince colleagues (and eventually their students), despite the confusion and frustration Sentimental Education often causes, Frédéric Moreau and his friends have much more in common with our own students—and therefore great insight to provide them—than the latter would likely ever imagine. No other nineteenth-century French novel better captures, not only through its historical content, but also through its distinctly modern literary style, the overwhelming anxiety and cultural disorientation of a young generation raised in an era of comparable upheaval and media-inspired epistemological indeterminacy.

Pedagogical context [1]

I had the life-changing good fortune to discover L’Education sentimentale during my very first term of doctoral work in Romance Languages and Literatures at the University of Michigan. My advisor, William Paulson, was teaching it in his undergraduate course on the representation of revolution in 19th-century French literature and graciously allowed me to sit in with the group. Under his intellectual and pedagogical guidance, then, not only did I fall in love with the novel that would most inspire my future academic work, but I was also able to witness the unique struggles and rewards of a virgin reading of L’Education with undergraduate students. There were certainly moments of frustration, boredom, and miscomprehension. More importantly and more frequently, though, there was also clear evidence of the students’ insightful engagement with the novel’s content and increasing ability to analyze its complex literary form and style. Ultimately, the majority of students finished the text much more knowledgeable about mid- nineteenth-century French cultural and intellectual history and as much more careful and sophisticated readers.

More than a decade later, I still relish reading L’Education sentimentale with undergraduates and look forward to the challenges and pleasures of the experience. Currently, I teach the text in a comparative literature course called “The Long Novel.” This course is targeted toward students (not necessarily literature majors) who simply wish to immerse themselves seriously in three specific nineteenth-century realist novels: Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield (1850), Gustave Flaubert’s L’Education sentimental (1869), and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamozov (1879). There are no expectations for previous knowledge of English, French, or Russian history or literature. “The Long Novel” is unique in that it is genuinely team taught by three literature professors: a Victorian specialist, a Russianist, and myself. Although each of us takes primary lead on class discussion of “our” novel, we are all three present for and participate actively in each session of the entire course. (We also share grading duties of all written assignments.) One of the more exciting pedagogical features of the course is that each of us takes a turn teaching the two other texts outside our field for a day. It is our hope that this non-conventional approach helps students experience each novel through three different national literary traditions and from both “expert” and “non-expert” viewpoints. Ultimately, our hope is to create a more open and diverse intellectual space in which students feel more comfortable with and invested in the discovery, understanding, and enjoyment of the richness these novels offer. [2]

Left: Plan de Nogent indiquant les lieux décrits dans L’Éducation sentimentale. http://www.amis-flaubert-maupassant.fr/article-bulletins/028_021/ Right: Illustration par André Dunoyer de Segonzac pour L’Éducation sentimentale, 1922. https://www.pinterest.fr/pin/416653403005299055/

When teaching the first two parts, then, I strive to point out to students the many ways Flaubert realistically represents the lives and mentalities of young people in subject positions very similar to their own. We witness the life-changing moment when young Frédéric Moreau first lays eyes on his great impossible love, Marie Arnoux (I.1), then his subsequent attempts to be taken seriously as an adult by the Arnoux couple. Frédéric hails from Nogent-sur-Seine but settles in Paris, returning home periodically. In Paris Jacques Arnoux runs a newspaper, is initially an art dealer, then porcelain factory owner, and finally vendor of religious artifacts, going bankrupt at several junctures, despite the large sum of money he borrows from Frédéric and never pays back. The Nogent characters include the Moreaus’ neighbor Old Roque, overseer of the noble financier Dambreuse’s property in Nogent. Frédéric’s social ascension in Paris, through a sizeable inheritance, will grant him entry to the Dambreuse salon, and he will, toward the end of the novel, become Mme Dambreuse’s lover. He will turn down marriage to Louise, Old Roque’s rich daughter who is madly in love with him and who will find solace with another Nogent character, Charles Deslauriers. A childhood friend of Frédéric, Deslauriers is also a law school student in Paris, and will spin in and out of the narrative like so many other characters. At law school, Frédéric will skip class, fail exams in humiliating fashion, then make excuses to himself and his mother for his failures (I.5-6). He will make and lose friends –mainly ambitious young men he knows from law school who represent a variety of political opinions, which they will display during the 1848 Revolution. They include the Socialist and later turn-coat Sénécal, a poor math tutor who lives off the charity of his better-off friends. Frédéric will party all night at wild dance clubs, and hang out all afternoon smoking and drinking with his gang, naively fantasizing about women they have yet to meet (I.5).

Paul Gaviani, L’étudiant en droit, 1840 http://droiticpa.eklablog.com/recent/2?noajax&mobile=1

As he matures, Frédéric will eventually consider different career paths, romantic possibilities, and struggle mightily to find his place in the face of great socioeconomic instability and the world-historical events of 1848. The 1840s are nonetheless defined by his involvement with women: Marie Arnoux, Jacques’s faithful and unhappy wife, who remains his life-long passion, although he cannot quite explain to himself why. He also shares the affection of Rosanette, a demi-mondaine supported by Arnoux (to the detriment of his family), until he becomes her lover and moves in with her in February 1848 just as the first gunshots are fired in Paris. They have a child together who dies in infancy, and Frédéric drifts into the arms of Mme Dambreuse, recently widowed, even contemplating marriage with her, but, as ever, unable to commit. Like Frédéric, she had financial “expectations.” He, initially, of an inheritance that he discovers might not materialize but then does. She presumes that she will get her husband’s vast fortune only to learn that he left all his money to his illegitimate daughter Cécile. Throughout the novel, love and money constantly intertwine, offering a ferocious vision of bourgeois life.

Berr, L’amour à Paris, 1847 http://le-bibliomane.blogspot.com/2011/03/hommage-iconographique-un-dessinateur.html

The 1848 Revolution [3]

Before considering less conventional approaches to reading and teaching this text, I would like briefly to remind colleagues of the rich historical detail found in Part III and also to suggest some questions for classroom discussion. Here (III.1-2), the revolution comes alive as readers experience the excitement and chaos of the February Days with the main characters, young Frédéric Moreau and his friends, many of whom are republican-leaning bourgeois college students. The long-anticipated and much-idealized revolution has finally arrived. What does the reality of it look like? How do characters react to the violence in the street surrounding them? Are they frightened? Excited? Enjoying themselves? Even disappointed? (309-317) Ask students to compare conservative and republican reactions to the event. Why does Frédéric’s acquaintance Dambreuse, for example, a rich banker and staunch conservative, suddenly (briefly) support the revolution? How should we interpret the painter Pellerin’s nonsensical representation of “…the Republic, or Progress, or Civilization, in the form of Christ driving a locomotive through a virgin forest” (323-24)? As events progress, how do characters like the authoritarian socialist Sénécal or the prototypical radical feminist Mlle Vatnaz react and how are they and their motivations portrayed? How is public political discourse described? Special attention should be paid to the representation of political club culture. An entire class period, for example, could be spent reading through and discussing the scathing depiction of the political meeting at the “Club de l’Intelligence” (326-334). Readers often conclude that Flaubert sides with reactionaries in the novel, but how might the description of conservative Old Roque’s brutality during the June Days challenge this interpretation? (364-365) Do any characters escape satirical critique? If so, what might this suggest about Flaubert’s ultimate judgement of revolutionary action and actors? How does the revolution eventually become co-opted by the forces of order (III.3-5)? Why is there such little narrative closure to the shocking events that occur on 2 December 1851 (450)? Indeed, any amount of time spent on serious discussion of Part III will enhance a student’s comprehension of the cultural and political history of 1848.

“Moral History of a Generation” [4]

The novel, however, is so much more than just a political chronicle of 1848. As its full title indicates, L’Education is also the sentimental histoire d’un jeune homme. It is through the life and love(s) of Frédéric Moreau that the reader will experience both the political and personal disillusionment of 1848. For this reason, I like to emphasize to students from day one that Sentimental Education is very much a bildungsroman, that is, the tale of a young person’s development and path to maturity. When the novel opens in 1840, Frédéric Moreau, is, in fact, just eighteen years old. Like many of our students, he has just matriculated, and, again like them, he is also overflowing with romantic ideas and ambitious personal and professional dreams for the future. On the fateful boat ride that takes him away from Paris (note the irony of a young nineteenth-century hero who is moving away from the capital toward the provinces at the beginning of the novel), he experiences a coup de foudre for Marie Arnoux, an older, married woman. Frédéric’s enduring obsession with Mme Arnoux will shape the course of the narrative. During these formative years, Frédéric and his generation will also experience the buildup and aftermath of the 1848 Revolution. What can we expect a young hero to learn in the face of such cataclysmic personal and political events? What should we conclude if neither Frédéric nor his generation mature at all by the end of the novel? [On day one, I also like to show students Delaunay’s Portrait de Flaubert adolescent to remind students that the writer was also once a young adult and not always the grumpy-looking older man we often imagine!]

Yet another cultural parallel to identify between the novel’s young characters and our students is the epistemological anxiety caused by the realization that our experience with reality is almost entirely mediated through “fake news,” photoshopped images, Facebook, Twitter, et j’en passe. This sense of living in an age of transmitted reality is inescapable in L’Education sentimentale, where nearly everything—ideals, desires, motivations, actions, speech—is ultimately revealed as inauthentic in some way or another. On both societal and political levels, the novel is replete with evidence attesting to the powerful and nefarious influence of mass print culture during the 1830s and 1840s. Flaubert provides numerous specific examples of the various forms of printed matter in circulation, as well as the pivotal role played by the information and opinions that these texts transmit. In addition to the literary and historical texts that inspire our characters from early childhood, Jacques Arnoux’s L’Art industriel, for example, is both an art gallery and a trade journal. Political and cultural discourse is shaped (and fortunes made and lost) by publications such as Le National, L’Illustration, Le Journal des mines, La Presse, La Revue indépendante, Le Siècle, La Revue des deux mondes, and L’Assemblée nationale, among others. It is worthwhile to ask students to trace the presence and influence of these texts and to consider the similarities and differences we face in our own over-mediated age.

Despite these commonalities, I have discovered that students still find it difficult to sympathize or identify with their nineteenth-century analogues. This should not be surprising, since young readers have reacted ambivalently or even negatively to the novel since its publication in 1869. On 9 January 1870, for example, George Sand wrote to Flaubert that her young friends were confused by the novel and that “[il] les a rendus tristes. Ils ne s’y sont pas reconnus, eux qui n’ont pas encore vécu, mais ils ont des illusions, et disent: ‘Pourquoi cet homme [Flaubert] si bon, si aimable, si gai, si simple, si sympathique, veut-il nous décourager de vivre?’”[5] A generation later, Ford Madox Ford famously quipped that one needed to read Sentimental Education at least fourteen times before understanding it fully or considering oneself a truly educated person. [6] Finally, in his influential 1937 essay “Flaubert’s Politics,” Edmund Wilson writes that “L’Education Sentimentale, unpopular when it first appeared, is likely, if we read it in our youth, to prove baffling and even repellent.” It is not until middle age, he continues, that readers are likely to have “seen enough of life” to truly appreciate its lessons.[7] Soit. My belief, however, is that we can indeed help our students better engage with the novel so that they may enjoy it much earlier in life and without multiple readings. In the final part of this essay, then, I would like to propose strategies and approaches that directly address specific difficulties that I have noticed students encounter with the text.

The most common student critique I have heard is that the novel is overly “confusing.” The most obvious reason for this confusion is also the most straightforward to discuss. For readers unaccustomed to the realist novel, the impressive level of descriptive detail can prove overwhelming. The very first sentence, in fact (“On the 15th of September, 1840, at six o’clock in the morning…”), announces the fine historical precision with which the story will unfold. From that point forward, the reader will encounter an understandably disorienting quantity of specific dates, details, names, locations, titles, and events. You might prepare students by providing a brief introduction both to the defining characteristics of literary Realism and to the historical period in question, especially concerning the phenomenon of repeated revolutionary action from 1789-1848 (most students are unaware, for example, that there was more than one French revolution). You could also remind students that it is not necessary to retain all of the specifics provided. In fact, although the novel is clearly written for an audience of contemporary readers, even someone in 1869 would have struggled—particularly in the constant whirlwind of Modern life —to keep track of all narrative details.

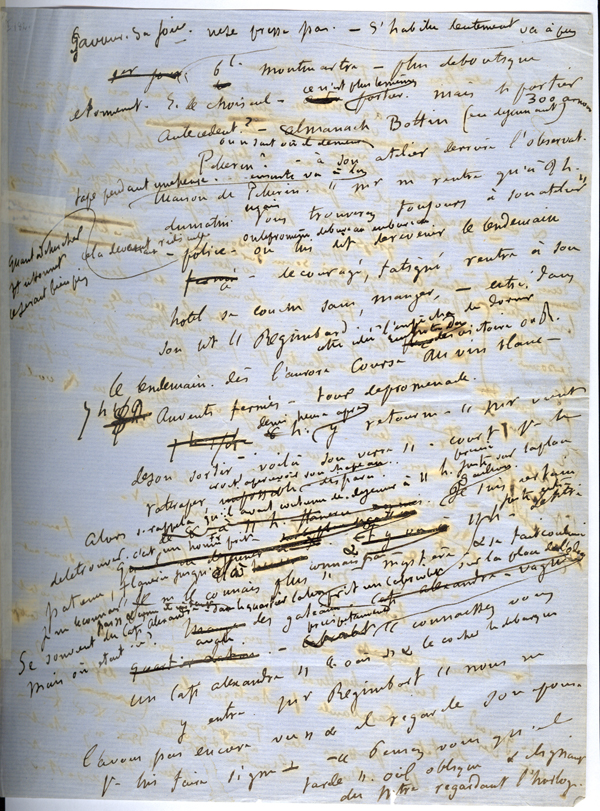

Brouillon du manuscrit de l’Édition sentimentale, flaubert_univ-rouen/jet/public/outils/aff_manus.php?g=13

More complicated is the intentional confusion inspired by Flaubert’s stylistic innovations. His goal was to achieve a seamless fusion of style and subject matter, one that erased the dichotomy between form and content. “La forme et l’idée, pour moi,” he wrote in December of 1857 to Mademoiselle Leroyer de Chantepie, “c’est tout un et je ne sais pas ce qu’est l’un sans l’autre.”[8] A powerful example of this is the uncertainty caused by repetitions that appear in the novel’s ring composition: the last two chapters (Frédéric’s final meeting with Madame Arnoux and his and Deslauriers’ reminiscences of their adolescent adventure at the brothel La Maison de la Turque) repeat, in order, the first two chapters (Frédéric’s first encounter with Madame Arnoux and, again, the young men’s memories of their botched visit to the brothel). Even within the narrative, Frédéric repeatedly finds himself in unmistakably similar situations or milieus. In addition to the parallel series of encounters with both Marie and Rosanette, for instance, there are the Dambreuse dinners, Frédéric’s law exams (which bookend chapter 5 of Part I), as well as Frédéric’s housewarming in Part II chapter 2 and Dussardier’s punch party in Part II chapter 6. It must be noted that the complexity created by this circular structure not only confuses readers, but also serves to illustrate repetition, stagnation, and disorientation in the lives of the characters themselves.

Finally, the most significant of Flaubert’s stylistic innovations is his masterful deployment of the style indirect libre. It is well worth the time to examine this narrative technique with students, taking care to consider its intentional effects on the reader. A clear example of these various forms of discourse is found at the very end of Part I, chapter 6. When Madame Moreau asks Frédéric what he plans to do in Paris after inheriting his uncle’s fortune, “What are you going to do there?” the question, in quotation marks, is directly attributed to a specific character. A bit later on, we see an example of indirect discourse: “They were sitting down to dinner when the church bell tolled three times, slowly; and the maidservant, coming in, announced that Madame Eléonore had just died.” The announcement that Madame Eléonore died is indirect (we don’t know the exact words used by the maidservant), but still easily attributed. Next, however, we read that “All things considered, this death was no great loss to anybody, not even the child. The girl would only be better for it, later on.” This judgment is clearly expressed, but unattributed. The reader therefore does not know who voiced this, but given what we already know about the petty insensitivity of the Nogentais notables, especially concerning the Roque family, we can only imagine this as part of a chorus of nasty gossip being shared by several people. In these moments, there is no identifiable storyteller to tell us what to think about a given utterance or situation. We are invited to participate on the ground level of the dialogue, but the information is often conveyed in an incomplete, fragmented manner. The reader must therefore take a much more active role in interpreting what is said, ultimately granting her greater interpretive responsibility and agency than more conventional narratives. [You may also consider asking more advanced undergraduates or graduates to read parts of Jonathan Culler’s The Uses of Uncertainty (Cornell UP, 1975) as a supplement to this discussion.]

Ultimately, L’Education sentimentale is neither easy to read nor to teach, but is remarkable enough from both a literary and historical standpoint to justify the extra preparation. For their efforts, students will be rewarded not only with uncommon historical insight, but also a novel that, thanks to its unique form, content, and style, offers a more realistic representation of our complex modern world than perhaps any other they have previously encountered.

Gustave Flaubert, Sentimental Education, Penguin Modern Classics, 2004.

NOTES:

- William Paulson’s book, Sentimental Education: The Complexities of Disenchantment (New York: Twayne’s Masterwork Studies, 1992) is an exceptionally rich and accessible resource for anyone teaching the novel.

- I would like to acknowledge my brilliant and inspiring Lawrence University colleagues Timothy Spurgin and Peter John Thomas, with whom I’ve had the great pleasure to teach the novel on two occasions.

- Sentimental Education (Penguin, 2004). All references are to this edition.

- In a letter dated 6 October 1864, Flaubert wrote to Mademoiselle Leroyer de Chantepie: “Je veux faire l’histoire morale des hommes de ma génération; « sentimentale » serait plus vrai.” In Flaubert, Gustave. Correspondance. Paris: La Pléiade, t. III, p. 409. Also available online: https://flaubert.univ-rouen.fr/

- Sand, George. Correspondance: 1812-1876. (C. Lévy, 1883-84), p. 353.

- As cited by Edmund White in “Moreau, C’est Nous,” review of Flaubert in the Ruins of Paris: The Story of a Friendship, a Novel, and a Terrible Year by Peter Brooks, The New York Review of Books 64, no.19 (December 7, 2017). Also available online: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/12/07/flaubert-moreau-cest-nous/

- Edmund Wilson, Flaubert’s Politics. Partisan Review 4, no.1 (1937): 13-24.

- Flaubert, Gustave. Correspondance. Paris: La Pléiade, t. II, p. 783. Also available online: https://flaubert.univ-rouen.fr/