Philip Dwyer

University of Newcastle, Australia

Jean-Claude Brisville (1922-2014) may be relatively unknown to English-speaking audiences, but his life as a professional writer spanned more than sixty years. His first play, Les Emmurés, was staged in 1945, and his first novel, Prologue, appeared in 1948. In the course of his writing career, he had a number of successes, but they were scattered rather than consistent over the years. It would be fair to say that Le Souper was his most successful work, opening at the Théatre Montparnasse in 1989 and playing for three years. It won the Grand Prix du théâtre de l’Académie française in 1990, and was transferred onto the screen in 1992 in a film starring Claude Rich who reprised his stage role as Talleyrand, and Claude Brasseur as Fouché. The film was directed by Édouard Molinaro, who among other things has done La Cage aux folles (1978) and Beaumarchais, l’insolent (1996),* also adapted by Brisville from a play by Sacha Guitry, with Fabrice Luchini as Beaumarchais.

The play opens on the evening of 6 July 1815, and centres almost entirely around a dialogue between two of the more notorious characters in Revolutionary and Napoleonic history – Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord and Joseph Fouché. The former was an ancien regime noble, an apostate bishop who convinced the National Assembly to nationalise Church property in 1789, and who went on to become Napoleon’s minister for foreign affairs. The other was a seminarian, a Jacobin and a regicide, who would go on to become Napoleon’s notorious minister of police. In both the play and the film, they are sitting around a dinner table at Talleyrand’s residence, rue Saint-Florentin (now the home of the American embassy), in a darkened salon, lit only by candles, discussing France’s political future. The play (and the film) opens and closes with two of Talleyrand’s valets, Jacques and Jean, whose complaining banter serve to bookend or frame the much more serious dialogue of their masters. Even the language is juxtaposed between the more familiar and even crude speech of the servants compared to the beautifully crafted French of the two protagonists.[1]

The play opens on the evening of 6 July 1815, and centres almost entirely around a dialogue between two of the more notorious characters in Revolutionary and Napoleonic history – Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord and Joseph Fouché. The former was an ancien regime noble, an apostate bishop who convinced the National Assembly to nationalise Church property in 1789, and who went on to become Napoleon’s minister for foreign affairs. The other was a seminarian, a Jacobin and a regicide, who would go on to become Napoleon’s notorious minister of police. In both the play and the film, they are sitting around a dinner table at Talleyrand’s residence, rue Saint-Florentin (now the home of the American embassy), in a darkened salon, lit only by candles, discussing France’s political future. The play (and the film) opens and closes with two of Talleyrand’s valets, Jacques and Jean, whose complaining banter serve to bookend or frame the much more serious dialogue of their masters. Even the language is juxtaposed between the more familiar and even crude speech of the servants compared to the beautifully crafted French of the two protagonists.[1]

The dialogue between Talleyrand and Fouché, and their portrayal, is what counts here, not the action. This is a sort of psychological drama that unfolds before the spectators’ eyes (a technique that Brisville used in other plays) as both characters are revealed to the audience. In this the portraits of the two men roughly follow their characterization in history. Talleyrand is the refined aristocrat, the consummate courtier, who hides and is generally in perfect control of his emotions. Fouché by contrast is unrefined (there is a passage where Talleyrand attempts to teach Fouché how to drink cognac, at which Fouché feels humiliated and throws the glass against a wall), violent in word and gesture (at one point, he kicks away Talleyrand’s cane), and even a little sadistic. This especially comes across in the way Fouché describes what happens to a man under interrogation. He confesses to the pleasure of creating fear, and of confronting a suspect with the “inavouable. Il faut voir sa figure à mesure qu’on le découvre: épouvantée, méconnaissable… Une bougie qui coule.”

The dialogue between Talleyrand and Fouché, and their portrayal, is what counts here, not the action. This is a sort of psychological drama that unfolds before the spectators’ eyes (a technique that Brisville used in other plays) as both characters are revealed to the audience. In this the portraits of the two men roughly follow their characterization in history. Talleyrand is the refined aristocrat, the consummate courtier, who hides and is generally in perfect control of his emotions. Fouché by contrast is unrefined (there is a passage where Talleyrand attempts to teach Fouché how to drink cognac, at which Fouché feels humiliated and throws the glass against a wall), violent in word and gesture (at one point, he kicks away Talleyrand’s cane), and even a little sadistic. This especially comes across in the way Fouché describes what happens to a man under interrogation. He confesses to the pleasure of creating fear, and of confronting a suspect with the “inavouable. Il faut voir sa figure à mesure qu’on le découvre: épouvantée, méconnaissable… Une bougie qui coule.”

The broad historical outlines too are correct, although it is not history that matters so much as the intellectual debate around the future of the French polity. The meeting between the two men is known to have happened on 6 July over a dinner not at Talleyrand’s, but rather at Wellington’s residence in Paris.[2] It is from there that they left together in a carriage to visit Louis XVIII at Saint Denis, where the king was staying before returning to Paris (he had fled France for Gand on Napoleon’s return in March 1815), and where they were admitted to an audience shortly before midnight. The political commentator and writer, François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand, was in an antechamber at Saint-Denis, when he saw Talleyrand and Fouché, arm in arm as it were, entering the king’s chambers. The sight of the two men together was so unusual that it led Chateaubriand to remark in his Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe, “Tout à coup une porte s’ouvre: entre silencieusement le vice appuyé sur le bras du crime, M. de Talleyrand marchant soutenu par M. Fouché; la vision infernale passe lentement devant moi, pénètre dans le cabinet du roi et disparaît.”[3]

Of course, we only have Chateaubriand’s word for it, and he was prone to dramatise. Moroever, this observation was written a long time after the event. The day after that audience, Louis entered Paris. An entente of sorts must have been reached between Talleyrand and Fouché even though they hated each other. The conceit of the play is that these two men were powerful enough to decide the future of France, and that they were divided along ideologicial lines. Fouché, who had helped Napoleon to power in 1799, is supposed to be in favour of a republic, while Talleyrand, one of the key players in the transformation of the republic to empire in 1804, wishes to see a return of the monarchy. Neither can act without the other. Brisville imagines a verbal struggle for power, both men trying to remain relevant in a world that has moved on. During the dinner, the people of Paris (much more present in the film) can be heard in the distance singing the Carmagnole, a popular revolutionary song during the early years of the Revolution. The threat of the people and of violent revolution hangs heavily in the air, and is a constant background presence.

I say it is a conceit because historically neither of these men had such power. It is true that both men had successfully intrigued against Napoleon in the past. Talleyrand had repeatedly plotted against Napoleon from about 1807 onwards and was instrumental in bringing back the Bourbons in 1814, persuading Alexander I of Russia that this was the best course of action. Fouché intrigued against Napoleon in 1815 after his return from Waterloo, persuading the deputies in the Chambers that Napoleon was about to use force against them, as he had done in Brumaire, and that they should demand his abdication. However, the decision about whether the Bourbon monarchy was going to be “restored” (a second time) was really a foregone conclusion and was a decision made by the Allies, not the French. In reality, it was not Talleyrand who was the kingmaker, but rather Wellington. And it was not Talleyrand, but rather the Baron de Vitrolles, a staunch supporter of the king and an ultra-royalist, who persuaded Fouché to accept the return of the Bourbons. It was, moreover, Wellington who obliged Talleyrand to accept Fouché into the government. This was not 1814 when the end of the empire presented the French elite with a number of possible political options. The play ends, however, with the two men having decided the destiny of France, or more precisely with Talleyrand persuading Fouché that the Bourbons be allowed to return. The people, who find expression in Talleyand’s two cynical valets, simply accept the fact that their fate, and the fate of the country, has been decided for them.

There are two historical “details” that are raised in the course of the dialogue and that go to the heart of the character of these two men. They both concern what might be regarded as political errors of judgement, and they both allow the protagonists to attack one another from a position of strength. The first has to do with Fouché’s Jacobin background and his involvement in some unsavoury events during the Terror. At Nantes, in November 1793, for example, at least 1,800 people were drowned after being stripped naked, tied together in batches and sent to the middle of the Loire in holed barges. When Lyons, the second largest city in France, a city that had revolted against Jacobin Paris, was taken by revolutionary troops in October 1793, the guillotine proved too slow; over 1,600 rebels were executed by cannon-fire and grapeshot besides previously dug mass graves. Fouché wrote to his friend on the Committee of Public Safety, Collot d’Herbois, after having taken the town of Lyons in December 1794. At the end of the short missive he wrote: “Goodbye, my friends, tears of joy are running from my eyes and inundating my soul.–P. S. There is only one way to celebrate this victory; two hundred and thirteen rebels are being struck down this evening by a thunderbolt.”[4] There is no doubt that Fouché had the blood of innocents on his hands. Worse, however, Fouché had the blood of Louis XVI on his hands and that, a point made in the play, was something that his brother, Louis XVIII, was hardly likely to forgive.

There are two historical “details” that are raised in the course of the dialogue and that go to the heart of the character of these two men. They both concern what might be regarded as political errors of judgement, and they both allow the protagonists to attack one another from a position of strength. The first has to do with Fouché’s Jacobin background and his involvement in some unsavoury events during the Terror. At Nantes, in November 1793, for example, at least 1,800 people were drowned after being stripped naked, tied together in batches and sent to the middle of the Loire in holed barges. When Lyons, the second largest city in France, a city that had revolted against Jacobin Paris, was taken by revolutionary troops in October 1793, the guillotine proved too slow; over 1,600 rebels were executed by cannon-fire and grapeshot besides previously dug mass graves. Fouché wrote to his friend on the Committee of Public Safety, Collot d’Herbois, after having taken the town of Lyons in December 1794. At the end of the short missive he wrote: “Goodbye, my friends, tears of joy are running from my eyes and inundating my soul.–P. S. There is only one way to celebrate this victory; two hundred and thirteen rebels are being struck down this evening by a thunderbolt.”[4] There is no doubt that Fouché had the blood of innocents on his hands. Worse, however, Fouché had the blood of Louis XVI on his hands and that, a point made in the play, was something that his brother, Louis XVIII, was hardly likely to forgive.

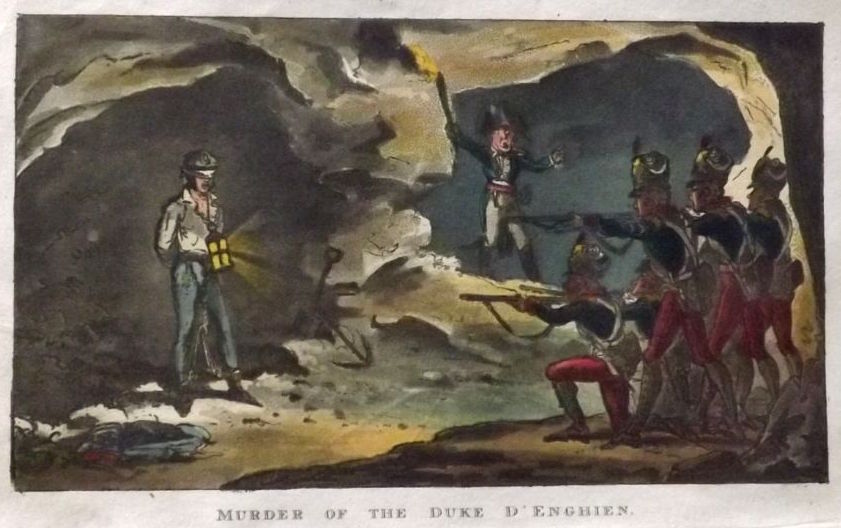

The second historical detail has to do with the execution of the Duc d’Enghien. The matter is raised by Fouché, who finds a portrait of the young prince hanging on the wall of the salon (in the film, on the floor facing a wall). Enghien, tenth in line to the throne in the Bourbon succession, was living in Ettenheim in Baden. He was kidnapped in March 1804 on the orders of Napoleon as a reprisal for an assassination plot, brought back to Paris and executed in the moat of the Château de Vincennes. In the play, Fouché conveniently produces a letter implicating Talleyrand in the affair. Such a document exists. Talleyrand let his views known to Napoleon a couple of days before the execution. It was, Talleyrand wrote, an occasion to resolve any concerns about the stability of the new imperial government. Napoleon had the right to defend himself. ‘If justice must punish rigorously, it must also punish without exceptions.’ Talleyrand’s suggestion was clear – in order to allay any fears that there might be a return of the former royal House, an example had to be set. After the execution, which shocked public opinion throughout Europe, Talleyrand is said to have quipped, “It is worse than a crime, it is a blunder,” although this is probably apocryphal and interestingly has also been attributed to Fouché.

The second historical detail has to do with the execution of the Duc d’Enghien. The matter is raised by Fouché, who finds a portrait of the young prince hanging on the wall of the salon (in the film, on the floor facing a wall). Enghien, tenth in line to the throne in the Bourbon succession, was living in Ettenheim in Baden. He was kidnapped in March 1804 on the orders of Napoleon as a reprisal for an assassination plot, brought back to Paris and executed in the moat of the Château de Vincennes. In the play, Fouché conveniently produces a letter implicating Talleyrand in the affair. Such a document exists. Talleyrand let his views known to Napoleon a couple of days before the execution. It was, Talleyrand wrote, an occasion to resolve any concerns about the stability of the new imperial government. Napoleon had the right to defend himself. ‘If justice must punish rigorously, it must also punish without exceptions.’ Talleyrand’s suggestion was clear – in order to allay any fears that there might be a return of the former royal House, an example had to be set. After the execution, which shocked public opinion throughout Europe, Talleyrand is said to have quipped, “It is worse than a crime, it is a blunder,” although this is probably apocryphal and interestingly has also been attributed to Fouché.

The play is a duel between two egotistical, cynical characters who deride the past, the people, politics and their own role in it. Does it represent two competing visions of France? As in any healthy democracy, there is always a public debate about what kind of country one should strive for, but in French history this kind of political deliberation over the future of the country has often resulted in violent clashes, revolts and revolutions. Of course, like any cultural representation of the past, whether novelistic or filmic, the play says much more about the period in which it was written than about the historical setting. The 1980s in France were dominated by the rise of the Socialist party and its leader François Mitterrand’s presidency from 1981 to 1995, so this may be an unwitting commentary by Brisville on contemporary politics. The people in the play are portrayed as menacing, but their potential for violence is being contained as they stand outside the windows of Talleyrand’s residence. They throw stones and break windows, shots are fired into the air, but they are politically passive, at times shown (in the film) expectantly awaiting the outcome of Talleyrand and Fouché’s deliberations. In the end, the crowd is dispersed not by troops but by rain. “La pluie est contre-révolutionnaire,” quips Talleyrand.

The play is a duel between two egotistical, cynical characters who deride the past, the people, politics and their own role in it. Does it represent two competing visions of France? As in any healthy democracy, there is always a public debate about what kind of country one should strive for, but in French history this kind of political deliberation over the future of the country has often resulted in violent clashes, revolts and revolutions. Of course, like any cultural representation of the past, whether novelistic or filmic, the play says much more about the period in which it was written than about the historical setting. The 1980s in France were dominated by the rise of the Socialist party and its leader François Mitterrand’s presidency from 1981 to 1995, so this may be an unwitting commentary by Brisville on contemporary politics. The people in the play are portrayed as menacing, but their potential for violence is being contained as they stand outside the windows of Talleyrand’s residence. They throw stones and break windows, shots are fired into the air, but they are politically passive, at times shown (in the film) expectantly awaiting the outcome of Talleyrand and Fouché’s deliberations. In the end, the crowd is dispersed not by troops but by rain. “La pluie est contre-révolutionnaire,” quips Talleyrand.

It is a wonderful turn of phrase but nevertheless one cannot help but think back to the neo-conservative interpretations of the crowd and the Revolution à la Schama that came to the fore in the 1980s. One cannot therefore entirely dismiss the timing of the play. 1989 was the bicentenary of the Revolution. At a time when the French nation and in particular the Socialist government of France was commemorating the achievements of 1789, Brisville chose to write a play that leaves the people out of the political process and which might be taken as celebrating moral corruption and political intrigue. This is not so much a coincidence as a reflection of a particular type of thinking about the people in the Revolution. In the end, Talleyrand and Fouché were accomplished puppet masters, but I am not entirely sure whose strings Brisville was trying to pull.

Jean-Claude Brisville, Le Souper (Paris: Actes sud-Papiers, 1989).

Edouard Molinaro, Director, Le souper: le vice au bras du crime, 1992, colour, 90 min, France, Trinacra, Parma Films, France 2 Cinéma.

* The film was reviewed by Tom Kaiser in Vol.1 issue 5 (2011).

- The servants’ dialogue is full of “argot” or slang, which may be beyond students studying French. I would, therefore, highly recommend the annotated edition by Delphine Cohen published by Hatier in 2010, whose footnotes explain not only the historical context, but also the meaning of some of the more obscure French words and references.

- Emmanuel de Waresquiel, Talleyrand (Paris: Fayard, 2003), pp. 505-7.

- The play and the film (read by a voice-over) both end with this quotation.

- Alphonse Aulard, Recueil des actes du Comité de Salut public, 28 vols (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1889-1951), ix. pp. 555-6 (20 December 1794).