Daniel Hobbins

University of Notre Dame

Fifteenth-century France has long proven popular as a setting for historical fiction. Victor Hugo set The Hunchback of Notre Dame in the Paris of 1482. Hella Haasse brought to life the world of the mad king, Charles VI, in her popular novel In a Dark Wood Wandering. Jacques Coeur – the subject of this beautifully written novel by Jean-Christophe Rufin – has himself been treated multiple times in fiction, most famously by Thomas Costain in The Moneyman (1947). Coeur was the argentier or royal bursar to Charles VII, charged with providing goods, especially luxury goods, to the royal household. The only thing more striking than his rise to dizzying heights of power and wealth was the catastrophe of his decline. His wealth had made him numerous enemies, eventually including even the king, and the sudden death of Agnès Sorel in 1450 led to the baseless accusation that Coeur had poisoned her. With the help of friends he eventually fled to Rome, where Pope Nicholas V welcomed him, but the era of his dominance was over. He died in 1456.

The only thing more striking than his rise to dizzying heights of power and wealth was the catastrophe of his decline. His wealth had made him numerous enemies, eventually including even the king, and the sudden death of Agnès Sorel in 1450 led to the baseless accusation that Coeur had poisoned her. With the help of friends he eventually fled to Rome, where Pope Nicholas V welcomed him, but the era of his dominance was over. He died in 1456.

Coeur is well-known to scholarship since at least the nineteenth century, but historians of the past generation have wrestled over fundamental questions of identity: should we think of him as a royal official and statesman, or instead primarily as a new kind of merchant-entrepreneur? [1] Such studies leave Rufin cold. They give the impression of a “wheeler-dealer, intriguer, and courtier who rose too high” (417-18). Rufin instead casts Coeur as a man in search of an identity – essentially a modern man inserted into the fifteenth century who rejects contemporary value systems for a new understanding of the power of money and commerce to reorder human relations. Beyond that, Rufin uses his career as a meditation on the power of dreams to shape the world – even if, in the end, one must abandon them.

Coeur himself narrates. The story begins at the end of his life on the Greek island of Chios, where he has fled from the agents of Charles VII who have come to kill him. He has managed to elude them so far, and now takes the opportunity to reflect on his life and career before it is too late. Looking back, he has much to be proud of and much to regret. As the story of his life unfolds, it becomes clear that Rufin is telling several different stories. From one angle, this is a story of how Coeur rose from obscurity to be the richest man in France by running the Argenterie. Essentially, Coeur receives the king’s permission to act as his chief importer, and thus to supply him with the luxury goods that he needs to dispense as bounty. His great insight in this position is to see, as he puts it, that “finance and commerce ought to be connected” (186). He has anticipated the department store credit card: the nobility covet his merchandise, so Coeur extends them loans. But by falling into debt, the nobles were putting a noose around their necks. Even the mighty princes were not immune. Coeur need not worry about his patrons defaulting on these loans. Should they refuse to pay, they would face the king’s wrath. Coeur gets rich and the king uses the money to build a modern army.

As the story of his life unfolds, it becomes clear that Rufin is telling several different stories. From one angle, this is a story of how Coeur rose from obscurity to be the richest man in France by running the Argenterie. Essentially, Coeur receives the king’s permission to act as his chief importer, and thus to supply him with the luxury goods that he needs to dispense as bounty. His great insight in this position is to see, as he puts it, that “finance and commerce ought to be connected” (186). He has anticipated the department store credit card: the nobility covet his merchandise, so Coeur extends them loans. But by falling into debt, the nobles were putting a noose around their necks. Even the mighty princes were not immune. Coeur need not worry about his patrons defaulting on these loans. Should they refuse to pay, they would face the king’s wrath. Coeur gets rich and the king uses the money to build a modern army.

But from another angle, this is a story of movement between different worlds. The success that Coeur enjoys allows him to move between different classes – from the world of trades and townspeople in which he grew up, to the world of princes and lords, the men who had brought the country to a state of ruin. But the movement is also geographical: Coeur’s wide travels take him to the Muslim world as well as to Italy. These journeys allow Rufin to bring this entire world to life. How did a medieval person feel upon seeing the ocean for the first time? Here we find out (74).

Coeur’s travels in the Muslim world brings on his first crisis. Toward the end of his trip, Coeur stops at an oasis near Damascus. Wandering among the camels of an immense caravan, he feels the call of the east and the unknown. He senses a great opportunity that he must seize or lose forever. The possibilities of this new path seem endless. But rejecting his former life would mean abandoning his family and the normal aspirations of a man of his station. Wracked by suffering, he resists the temptation, so closing the door to a life of myriad possibilities. I suppose it is a moment everyone faces, if not this dramatically. For Coeur there is now only one life, only one possibility: a wife, children, and a striving for riches and happiness.

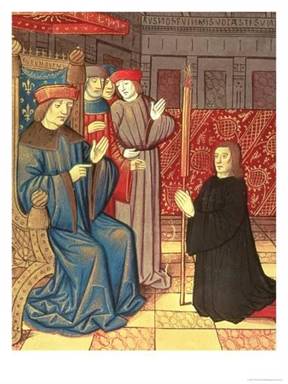

Coeur’s big break comes when a former partner in crime – they had debased the coinage and pocketed the proceeds – obtains for him a private audience with the king. Eventually, the king appoints him as royal argentier. With the help of his loyal business partners, Coeur puts into motion his scheme to draw France into the Mediterranean trade network. Exotic goods soon pour into the Argenterie, and covetousness reigns at the royal court. Coeur now has power over the nobles who humiliated his father, but will do anything to maintain their appearance. He soon possesses wealth beyond his wildest imaginings.

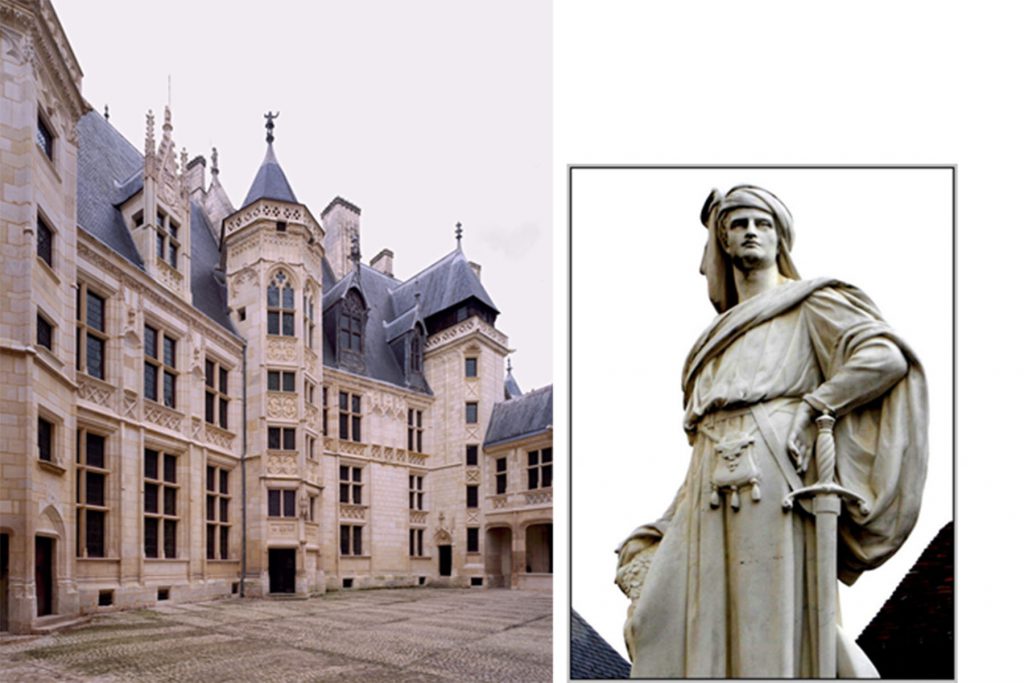

Unlike his companions who have helped him build his vast financial empire, Coeur cannot simply enjoy the material pleasures or the business of finance itself, selling, importing, and speculating. He begins instead to collect castles, as he says, out of nostalgia for the lost world of chivalry. His first castle was owned by a nobleman who had fallen into debt at court and was forced to sell off the estate. His visit there lasts three days. The peasants watch in amazement as a merchant, “the son of a nobody,” takes possession of their castle. In such a world, anything is possible. Just as in his experience outside Damascus, Coeur approaches the threshold of another world. He wanders alone through the many rooms and the vast halls, searching through old trunks, grasping for odors and memories of this lost world. But it is a world that he can never inhabit because he never belonged there except in his imagination. Yet he feels tempted by these lives that are forever inaccessible to him. His collection of castles allows him to dwell in the past. It is his great misfortune: he is wealthy but has lost the possibility of enjoying the present. He is the prisoner of a past that does not even belong to him.

The book is an unalloyed pleasure to read in this superb translation by Alison Anderson. I suppose that in twenty years, if I forget all else, I will remember the marvelously drawn characters. Charles VII is a “wounded, jealous, mean man” (198), his gnarled body twisted against nature, his breath noxious, his very eyes seeming to look in different directions, a vision of suffering and doubt. The famous Agnès Sorel, his mistress, is a tragic figure, perfect in her beauty and yet delicate, her skin diaphanous, her life sacrificed to the insatiable lust of the king. Atmospherically, the world in which Coeur lives and moves seems somehow overripe, and indeed the shadow of Johan Huizinga’s Autumn of the Middle Ages still falls heavily on these pages: everywhere we see unfulfilled cravings, excess and decay, exaggerated piety, chivalry kept alive out of sentimental nostalgia. Coeur lives in a world where men have forgotten the old chivalric values, which survive only in the imagination, the longing for the days before the mad king, Charles VI. The customs that survive from that time bend under the weight of an artificial luxury that devours its participants by its expense even as it enriches Coeur. The tournament is now chiseled into a complex but ridiculous ritual. At the pas d’armes of Châlons, Coeur finds the great knight Jacques de Lalaing, “a hero straight from the legends of King Arthur” whom everyone adores, to be a total imbecile, straining to keep up the appearance of a heroic knight errant of the days of yore. Coeur sees instead the patches on his clothing, the bones of his malnourished horses, the cracked leather of their harnesses. Everything is a sham. The dream of the world of chivalry turns out to be fiction.

Atmospherically, the world in which Coeur lives and moves seems somehow overripe, and indeed the shadow of Johan Huizinga’s Autumn of the Middle Ages still falls heavily on these pages: everywhere we see unfulfilled cravings, excess and decay, exaggerated piety, chivalry kept alive out of sentimental nostalgia. Coeur lives in a world where men have forgotten the old chivalric values, which survive only in the imagination, the longing for the days before the mad king, Charles VI. The customs that survive from that time bend under the weight of an artificial luxury that devours its participants by its expense even as it enriches Coeur. The tournament is now chiseled into a complex but ridiculous ritual. At the pas d’armes of Châlons, Coeur finds the great knight Jacques de Lalaing, “a hero straight from the legends of King Arthur” whom everyone adores, to be a total imbecile, straining to keep up the appearance of a heroic knight errant of the days of yore. Coeur sees instead the patches on his clothing, the bones of his malnourished horses, the cracked leather of their harnesses. Everything is a sham. The dream of the world of chivalry turns out to be fiction.

Coeur contrasts this decrepitude with the world of merchandise and trade, the bond that unites all humans without regard to birth, honor, and faith. Beyond these human inventions stand the humble necessities of life such as food, clothing, and shelter. Coeur finds the future, as well as everything good, in Italy. It is a view passed down intact from Burckhardt that has successfully weathered a century of scholarship. In Genoa, he speaks to everyone in the new, universal language of money. In Florence, he finds a place where the nobility still value their castles and lands, the old “feudal order,” but also embrace work in trade or industry. He realizes to his happy surprise that the two can live in harmony. He falls under the spell of Art – not the art he has always known, the hereditary work of artisans passed down through generations, but the Art of genius and innovation. He realizes that to become the center of the world, France must not only amass wealth but embrace the creativity of the human spirit. He must now find and nourish the prophets of this new religion.

As for religion, Coeur has never had much time for it, and he leaves it to his wife, described as a “pious upstart” (159). The Great Schism leads him to harbor “insolent, secret thoughts” (288). It undermines the argument for God’s omnipotence, for it shows that he cannot even manage his own affairs properly. Henceforth, Coeur would conform to the customs of religion only as obligations. He finds a kindred spirit in Pope Nicholas V, a man of no real faith who uses religion as a masquerade for his true passion: antiquity. He takes more consolation from Seneca than from the Gospels. He supports a new crusade mostly to rescue the classical treasures of Byzantium. Ultimately, his interest in ancient culture even opposes true religion.

It undermines the argument for God’s omnipotence, for it shows that he cannot even manage his own affairs properly. Henceforth, Coeur would conform to the customs of religion only as obligations. He finds a kindred spirit in Pope Nicholas V, a man of no real faith who uses religion as a masquerade for his true passion: antiquity. He takes more consolation from Seneca than from the Gospels. He supports a new crusade mostly to rescue the classical treasures of Byzantium. Ultimately, his interest in ancient culture even opposes true religion.

I suppose that the historian should expect such liberties, no less than when dealing with films on historical subjects. But by its nature historical fiction does seem to have a greater capacity for equivocation, or the claim to represent historical truth under the guise of fiction. This point deserves some reflection. In fact, Rufin reflects an older tradition of scholarship on late medieval religion. For much of the last century, the dominant view of late medieval religion saw the Church as a broken institution. Of course structurally this is hard to deny at least after 1378 with the outbreak of the Great Schism, perhaps even through much of the fourteenth century, when the popes resided at Avignon. But this was seen as merely the outward manifestation of inner rot. The Black Death exposed the inability of the clergy to deal with such a catastrophe, and thus undermined their spiritual authority. Their growing wealth undermined their spiritual role and encouraged both opposition and reform.

It would seem safe to say that this older view cannot really be sustained in its original form. Scholars today speak of the late medieval Church as full of vitality and creativity, bounteous in its options. For the laity, the parish offered a wide field for creative energy, the chance to play an active role in the community. Those choosing the religious life had more options than ever before, even the possibility of choosing piety while remaining in the world, as we see with the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Parish clergy enjoyed expanding educational horizons and routinely had personal libraries of some significance. Meanwhile, nearly every major religious order launched reforms that addressed contemporary critics and introduced a fervent devotional culture. A similar reorientation applies to our understanding of chivalry. The great age of knightly orders was just on the horizon. One of the greatest orders, the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece, was founded only in 1430, just as Jacques Coeur was coming of age. I do not mean to say that Rufin should have incorporated this more recent understanding of late medieval religion or knighthood into the fabric of his novel. Most of it is well outside of his primary theme. But one still wonders what a fictional account might look like that took late medieval religion seriously.

We should not mistake Rufin’s Coeur with the historical Jacques Coeur. In his mental outlook, Coeur appears to have been a man of his times who harbored entirely conventional religious views and who even admired Jacques de Lalaing. In the “Postface,” Rufin admits that his portrait resembles himself, Rufin, more than it does Coeur. I suspect that the historical Coeur would find this portrait completely unrecognizable. But as a first approach to the man and to the period under the veil of fiction, The Dream Maker is a triumph.

Jean-Christophe Rufin, The Dream Maker. Trans. Alison Anderson. New York: Europa, 2013.

NOTES

- For an introduction to the historical Jacques Coeur, see Kathryn L. Reyerson, Jacques Coeur: Entrepreneur and King’s Bursar (New York, 2005).